Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the role of the Patient Safety Incident Response Framework (PSIRF);

- Understand the difference between the PSIRF and the Serious Incident Framework;

- Know how the PSIRF can be applied to the pharmacy profession.

Ensuring the safe and effective use of medicines is a central function of the pharmacy team. Great effort is made by the profession to reduce risks to the public, but there are still large numbers of medication-related safety incidents, with as many as 237 million incidents estimated to occur annually at some point in the medication process in England alone[1]. While a small number of high-profile medication safety incidents sometimes make front-page news, these represent the extreme end of the spectrum. It is the millions of other less extreme medication-related incidents that, when taken cumulatively, represent a major cause of iatrogenic harm across healthcare, not just in the UK but worldwide[2]. As pharmacy professionals, there is an ongoing obligation to contemplate patient safety and ensure that incidents result in improvements that can prevent future harm.

Patient safety is a discipline that looks to ensure that patients do not suffer any avoidable harm as a result of the healthcare they receive[3]. This requires a complex combination of both strategic- and operational-level activity. Pharmacy professionals working in all areas of practice are in an optimal position to contribute to medicine safety. Pharmacists provide access to medications and information for both patients and other healthcare professionals, and are responsible for medicines-related governance. Additionally, as pharmacists assume expanded roles delivering advanced services and increased levels of prescribing, this responsibility for patient safety is set to grow further[4].

To improve the quality, effectiveness and safety of healthcare services, patient safety must be combined with quality improvement[5]. Quality improvement is the process of understanding an issue and then planning, implementing and sustaining a solution to it[6]. Effective quality improvement relies on the use of a structured approach, collaboration between staff and patients, and effective measurement of change; pharmacy professionals should be involved at all stages of the process[7]. Quality improvement can facilitate sustained changes and allows for an iterative approach, where processes are continuously improved and refined over time. In many healthcare organisations, patient safety and quality improvement are treated as separate entities but, without the support of quality improvement tools, efforts to improve patient safety are unlikely to succeed[5]. To improve the safety of healthcare services, there needs to be a close relationship between these disciplines.

The Patient Safety Incident Response Framework (PSIRF), published by NHS England in 2022, goes part way towards achieving this closer relationship[8]. The framework changes the way that patient safety incidents are managed, emphasising the learning and improvement that occurs after an incident happens[8]. The PSIRF replaces the Serious Incident Framework (SIF), and encourages the use of systems and approaches to patient safety and improvement. The PSIRF is still in the early stages of implementation and it is important that pharmacists understand the underlying rationale for the change and how to incorporate it into professional practice.

Root cause analysis

Prior to the adoption of the PSIRF, patient safety incidents would be investigated using a root cause analysis (RCA) approach[9]. RCA is a technique originating from other safety critical industries and aims to evaluate the underlying causal factors leading to an incident — the so-called ‘root causes’. A root cause is a discrete element, or number of elements, within a process or procedure that does not go to plan, resulting in the outcome being different to what was expected[10]. In healthcare, this may result in a patient safety incident.

There are several tools used for the practical application of RCA and these include the well known ‘five whys’ methodology, where an initial cause is identified and explored further by asking ‘why’ a further five times to drill into the initial statement and identify the true point of origin for the failure[11].

Despite RCA having a successful track record in other industries, it is necessary to question whether it is the right choice for use in a system as complex as modern-day healthcare, in which so many roles, systems and processes are interconnected and overlap. By viewing causal factors in a linear relationship with an incident, RCA inhibits its exploration from a systems perspective and may fail to recognise the various influencing factors that could have led to an incident occurring[9].

Taking the example of a hypothetical medication incident, RCA may identify the pharmacist involved in the final accuracy check of a dispensed prescription as the cause. This may result in this individual being subject to a formal investigation process, further training or even disciplinary action. Now, consider that a different pharmacist makes the exact same error two weeks later; in this situation, it could be argued that the RCA process has failed to identify a systemic issue and has failed in its task of preventing the error from reoccurring.

A further limitation of RCA is that there is a risk that it can contribute to healthcare staff fearing the consequences of reporting patient safety incidents out of concern that they will become subject to formal processes that could impact on their career[12]. Reflecting on the fictional example above, the second pharmacist to make the error would perhaps think twice before reporting the incident, having witnessed what had happened to their colleague. To understand the issues threatening patient safety in a healthcare system, and to implement improvements, it is vital that staff feel they can report incidents without fear of retribution[13]. We can therefore see how the RCA method may be incongruous with creating a culture for improving patient safety. It is important to state that this does not mean that appropriate measures should not be taken when an individual’s actions are thought to be putting patients at risk of harm, rather that the process of incident investigation should consider both the role of the individuals involved, as well as the whole system in which the process sits[14].

Another common critique of the SIF was the use of harm levels as a criteria for deciding whether to initiate an investigation[15]. Defining what to investigate in this way is flawed if we look from the perspective of Heinrich’s Triangle (see Figure 1). This theory posits that severe incidents normally occur after a larger number of lower-severity incidents[16]. The theory states that if organisations focus their efforts on preventing lower-acuity incidents, there should be a corresponding reduction in the number of more serious or fatal incidents that follow.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

It can be helpful to apply this theory to a clinical scenario.

Scenario: Dispensing errors

In a busy hospital pharmacy, the brands of prednisolone and propranolol have recently changed to look-alike/sound-alike (LASA) brands. There have been a couple of near-miss dispensing errors that were caught by a final checker before making it to the ward. One week later, there was a minor incident where the same error got past the final checker to reach the ward but the medication was not administered to the patient.

Reflective questions:

- What would the response be to this scenario if a root cause analysis approach was used? How might this differ if a systems-based method is applied instead?

- What possible contributory factors can you think of and how might they be managed to reduce the risk of reoccurrence?

Discussion:

Under the Serious Incident Framework, these errors would not have necessitated an investigation. However, had the medicine been administered to a patient and resulted in serious harm or death, an investigation would have been mandated. In contrast, the PSIRF would allow for a systems-based thematic analysis to be conducted based on a trend in incidents; this would allow the identification of wider factors contributing to the safety failure (e.g. new staff in procurement unaware of LASA medication; increase in demand for one of the medications owing to a guideline change; or organisational pressures to control costs and procure medicines from the cheapest supplier) and the development of an intervention that reduces or eliminates the risk of a dispensing error.

In this scenario, it is again easy to imagine how an RCA approach may have focused on the actions of individuals involved, potentially resulting in disciplinary procedures or retraining. The RCA process would be unlikely to take into account that the same individuals may have prevented the error many times previously and would fail to ask wider questions (e.g. whether a new team member would make the same error the following week).

Patient Safety Incident Response Framework

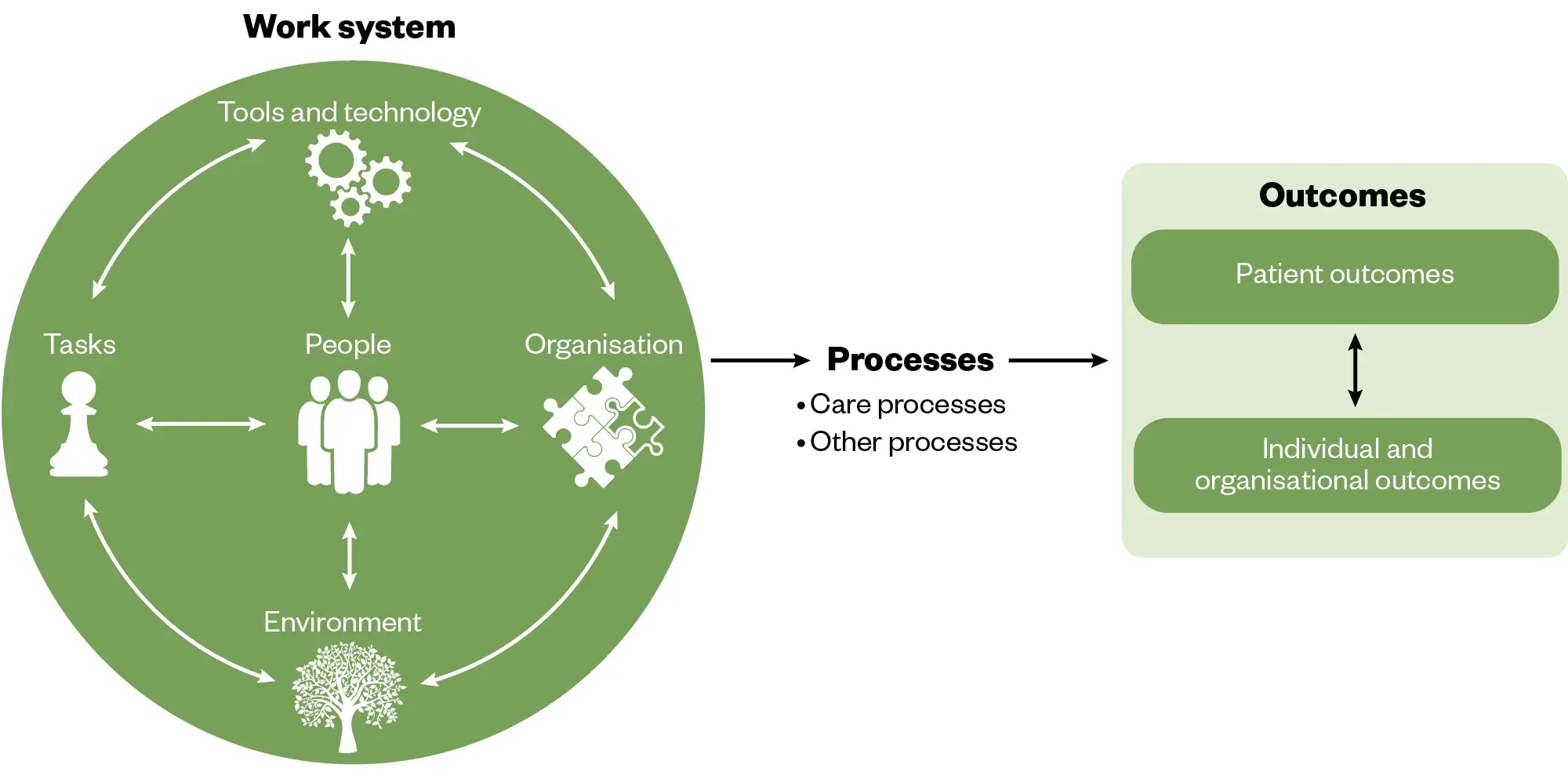

The systems model that the PSIRF is based on is called the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS)[8]. SEIPS (see Figure 2) is a framework used to understand the results produced by complex systems, such as healthcare[17,18]. The theory proposes that outcomes in complex systems are the result of multiple interactions between the work system and the processes that occur within it[17]. Therefore, if we want to understand a patient safety issue or learn from an incident, it is important that we understand the processes and the work systems that have led to the adverse event.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

The PSIRF has four main aims (see Box 2) and uses the SEIPS model to facilitate better learning after incidents, more effective improvements and a reduction in the risk of incidents reoccurring[8].

Aims of PSIRF

- Compassionate engagement and involvement of those affected by patient safety incidents;

- Application of a range of system-based approaches to learning from patient safety incidents;

- Considered and proportionate responses to patient safety incidents;

- Supportive oversight focused on strengthening response system functioning and improvement.

The PSIRF introduces several changes when compared with the SIF, which are summarised in Table 1 below[19].

Implementation of PSIRF

The PSIRF is still in the early stages of implementation. Given its relative flexibility when compared with the SIF, it is likely that each organisation will adopt a slightly different approach suited to the needs and patient safety incident profile of the specific organisation. For example, in some settings, falls that result in harm may be an issue that warrants a full patient safety incident investigation to understand the factors behind them. In other organisations, the causes behind this may be well understood, with resources better applied to generating improvements that further reduce risk of falls.

An important question for the pharmacy profession is how the PSIRF is likely to impact its capacity to improve patient safety. Looking at the medication error example above, we saw how RCA may have identified individual staff actions as the causative factor, with an investigation only initiated following a fatality. Under the PSIRF, organisational awareness and oversight of its patient safety incident profile might have alerted us to a trend in incidents surrounding the two LASA drugs at any earlier point.

Using SEIPS, we would gain a more holistic systems understanding of the influencing factors leading to a patient safety incident. This has been illustrated below using our fictional medication incident.

Pharmacy professionals should familiarise themselves with their organisation’s patient safety incident response plan and policy. These documents will contain information on specific objectives and priorities in relation to patient safety improvement and should provide background information on the patient safety issues faced by their organisation and how they plan to improve them.

As the PSIRF becomes more embedded within practice, it is important that individuals involved in investigations have an adequate level of training. The framework states that training should be provided by accredited training providers and these can be accessed through NHS England.

Pharmacy teams should engage with the patient safety and quality improvement teams within their organisations to ensure that any medicines-related patient safety priorities are included in organisational plans and priorities. Safety is at the heart of the pharmacy profession and it is well placed to contribute to its improvement.

- 1Elliott RA, Camacho E, Jankovic D, et al. Economic analysis of the prevalence and clinical and economic burden of medication error in England. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;30:96–105. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010206

- 2Medication Without Harm. World Health Organization. 2017. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/255263/WHO-HIS-SDS-2017.6eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed March 2024)

- 3Patient safety. World Health Organization. 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety (accessed March 2024)

- 4Keeping patients safe: being open and honest when things go wrong. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2024. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/keeping-patients-safe-june-2022.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 5Gupta M, Soll R, Suresh G. The relationship between patient safety and quality improvement in neonatology. Seminars in Perinatology. 2019;43:151173. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2019.08.002

- 6Jones B, Kwong E, Warburton W. Quality improvement made simple: What everyone should know about health care quality improvement. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2021/QualityImprovementMadeSimple.pdf. 2021. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2021/QualityImprovementMadeSimple.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 7Jones B, Vaux E, Olsson-Brown A. How to get started in quality improvement. BMJ. 2019;k5408. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k5437

- 8Patient Safety Incident Response Framework. NHS England. 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/B1465-1.-PSIRF-v1-FINAL.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 9Peerally MF, Carr S, Waring J, et al. The problem with root cause analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;bmjqs-2016-005511. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005511

- 10What is root cause analysis? American Society for Quality . 2024. https://asq.org/quality-resources/root-cause-analysis (accessed March 2024)

- 11Five whys. NHS Improving Quality. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2015/08/learning-handbook-five-whys.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 12Martin-Delgado J, Martínez-García A, Aranaz JM, et al. How Much of Root Cause Analysis Translates into Improved Patient Safety: A Systematic Review. Med Princ Pract. 2020;29:524–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000508677

- 13A just culture guide. NHS England. 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/patient-safety/patient-safety-culture/a-just-culture-guide/ (accessed March 2024)

- 14Oliver D. David Oliver: Accountability—individual blame versus a “just culture”. BMJ. 2018;k1802. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1802

- 15The future of NHS patient safety investigation. NHS Improvement. 2018. https://www.the-pda.org/wp-content/uploads/The_future_of_NHS_patient_safety_investigations_for_publication_proofed_5.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 16Yorio PL, Moore SM. Examining Factors that Influence the Existence of Heinrich’s Safety Triangle Using Site‐Specific H&S Data from More than 25,000 Establishments. Risk Analysis. 2017;38:839–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12869

- 17Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh B-T, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:i50–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.015842

- 18Holden R, Carayon P, Gurses A, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics. 2013;56:1669–86.

- 19Guide to responding proportionately to patient safety incidents. NHS England. 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/B1465-3.-Guide-to-responding-proportionately-to-patient-safety-incidents-v1-FINAL.pdf (accessed March 2024)