Shutterstock.com/Mclean

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Describe what is meant by the terms ‘quality’ and ‘quality improvement’ (QI);

- Explain the importance of QI in practice and outline common models, methods and tools;

- Understand how to apply QI methods in pharmacy and other healthcare settings;

- Identify a quality issue, define the problem, apply QI methods, evaluate and disseminate the outcomes.

Introduction

Across the UK, the NHS is required to continuously pursue improvements in the efficiency, safety and delivery of patient care in the most cost-effective manner[1–4]. To achieve this, healthcare leaders and policymakers have drawn learnings from other high-pressure, high-risk industries, such as manufacturing and aviation, adopting the quality improvement (QI) philosophies and methods first developed by these industries[5,6].

QI is now a strategic component of healthcare delivery that seeks to promote patient safety, enhance clinical effectiveness and encourage professionals to deliver a positive patient experience and promote equity[7,8]. The COVID-19 pandemic required healthcare professionals to quickly reconfigure services and embrace new ways of delivering care at unprecedented pace; however, the deployment of QI initiatives has primarily been reported at project and organisational level[9]. With QI practice now embedded throughout the NHS, there is a need to upskill the workforce at an individual level to ensure QI methods are commonly understood and become widespread at all levels of practice[10]. This article will introduce and define the term ‘quality’ and discuss the main QI methods and approaches.

What is quality in healthcare?

The concept of quality is never static. It should be viewed within a process of continuous improvement constantly driving to make healthcare practices safer, more effective, patient-centred, evidence-based, timely, efficient, equitable and sustainable[11]. There is no universally accepted definition when it comes to quality in healthcare, but it is helpful to consider some that have been applied to the term. The Institute of Medicine considers quality to be the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge”[12].

The Institute of Medicines defined six ‘dimensions’ of quality: safety, effectiveness, patient-centredness, timeliness, efficiency and equity[12]. Similarly, the NHS describes high quality care as being one that is “effective, safe, and provides as positive an experience as possible”[13].

Many factors affect patient perceptions of the quality of healthcare. The most common are patient–provider communication, access to healthcare including appointment and provider accessibility, shared decision making, provider knowledge and skills, and physical environment[14].

Quality standards in pharmacy

The UK Pharmacy Quality Scheme (PQS) was developed as part of the community pharmacy contractual framework for assessing the quality of care in community pharmacy[15]. It supports delivery of the ‘NHS long-term plan’ through the provision of financial incentives to pharmacy providers that meet quality criteria in three dimensions: clinical effectiveness, patient safety and patient experience[3,15]. Each PQS domain has several criteria that have been developed to permit flexibility in the way quality indicators are set. For example, indicators developed for the 2021/2022 scheme include criteria for patient safety, health-outcome improvement and health inequalities that were identified as a consequence of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic[16].

In addition, there are other quality standards and indicators for evaluating quality of care. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has developed standards and indicators for areas of care in which variations in current practice have been identified. They consist of a set of standards and information on how to measure progress[17]. The Care Quality Commission, as the independent regulator for English health and social care, has essential quality standards developed with the purpose of helping providers deliver safe, effective, compassionate care through continuous improvement[18].

Defining QI

The characteristics of QI can be defined in several ways. For instance, some definitions focus on the patient experience:

“… Better patient experience and outcomes achieved through changing provider behaviour and organisation through using systematic change methods and strategies”[19].

Other definitions emphasise organisational processes, or view QI as a more collaborative approach:

“… Deliberate and defined methods in continuous efforts to achieve measurable improvements in the efficiency, effectiveness, performance, accountability, outcomes, and other indicators of quality in services or processes”[20].

“The combined and unceasing efforts of everyone to make the changes that will lead to better patient outcomes (health), better system performance (care) and better professional development (learning)”[21].

There are several methods of improving care delivery, including audit, service evaluation and research. While these approaches share certain similarities and common underlying principles, QI has some distinguishing characteristics[22,23]:

- Understanding the problem from a range of perspectives;

- Understanding systems and processes within the service;

- Collaboration and engagement;

- Analysing demand, capacity and flow;

- Developing and testing potential solutions;

- Implementing and sustaining the solution.

Common QI approaches

QI involves taking a coordinated approach to solving a problem and the people involved need to be equipped with the necessary skills and resources.

A range of QI tools, methods and approaches have been developed over time. While all have value, it is more useful to adopt a combination of contextual-based approaches with an emphasis on the underlying principles, rather than focus on specific methods[24]. (See examples provided in Box 1 and Box 2).

Box 1: Illustrative examples of QI in primary care

Example 1: Community pharmacy

Project title: Application of process mapping to understand integration of high-risk medicine (HRM) care bundles within community pharmacy practice[25].

Aim: To understand how pilot pharmacies integrate novel HRM care bundles into routine practice. Care bundles were defined as a “structured way of improving the processes of care and patient outcomes: a small, straightforward set of evidence-based practices”. The project aims to improve patient safety by implementing safety interventions using a team-based approach.

QI method/tool: Pharmacy teams were trained in the ‘Plan Do Study Act’ (PDSA) approach to facilitate rapid testing of small-scale changes[26].

Outcome: The findings of the project allowed development of a generic process map applicable to warfarin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) care bundle implementation.

Example 2: Community pharmacy

Project title: Improving the safety of medication dispensing in primary care by combining human factors and quality improvement sciences[27].

Aim: To minimise the occurrence of dispensing errors in community pharmacies though a combination of awareness training and action in human factors and quality improvement (QI) methods.

QI method/tool: Training in the application of ‘model for improvement’, including use of run charts, and introduction to a range of patient safety improvement tools, including process mapping, Achieving Behaviour Change (ABC) for Patient Safety toolkit and PDSA approach.

Outcome: Statistically significant reductions in dispensing errors. Participating teams demonstrated that quality improvement methodologies can be accommodated into the busy dispensary routines.

Example 3: General practice

Project title: Evaluating the implementation of a QI process in general practice using a realist evaluation framework[28].

Aim: To support the implementation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance on non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs).

QI method/tool:

1. The model for improvement (aims to accelerate innovation adoption, working alongside existing change models including PDSA cycle);

2. Complexity and change systems theory (consider organisational components and interactions). The GP, pharmacist, quality improvement team members and patients were all stakeholders;

3. Clinical microsystems theory (systems approach but places the patient at the centre of a small, frontline network operating as part of a larger system).

Outcome: QI programme delivered practice change and improvements in legacy outcomes.

Box 2: Illustrative example of quality improvement in secondary care

Project title: Applying quality improvement (QI) methods to address gaps in medicines reconciliation at transfers of care from an acute UK hospital[29].

Aim: Improving the provision of information and documentation of reliable medication lists to enable clear, timely communications on discharge.

QI method/tool: Process mapping identified the various stages of medicines reconciliation in the hospital. ‘Plan Do Study Act’ (PDSA) cycles further informed the study at the beginning and as it progressed[26].

Outcome: New processes were put in place that led to a sustained reduction in unreconciled medications and this led to improvements to documentation of patients’ discharge summaries.

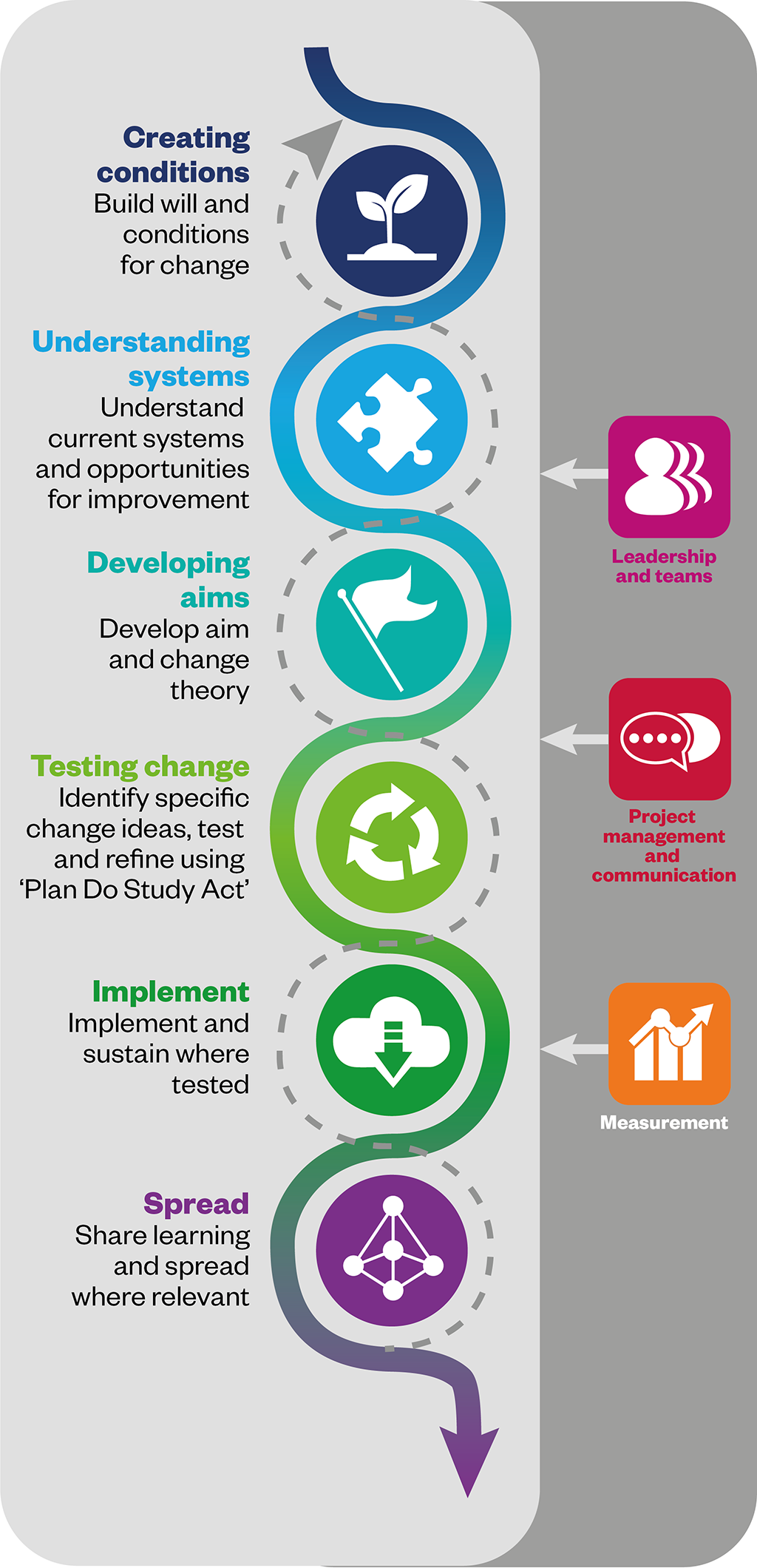

Some common QI approaches are summarised below.

‘Plan Do Study Act’

This approach to QI involves answering three main questions[26]:

- What are we trying to accomplish?

- How will we know that a change is an improvement?

- What changes can we make that will result in improvement?

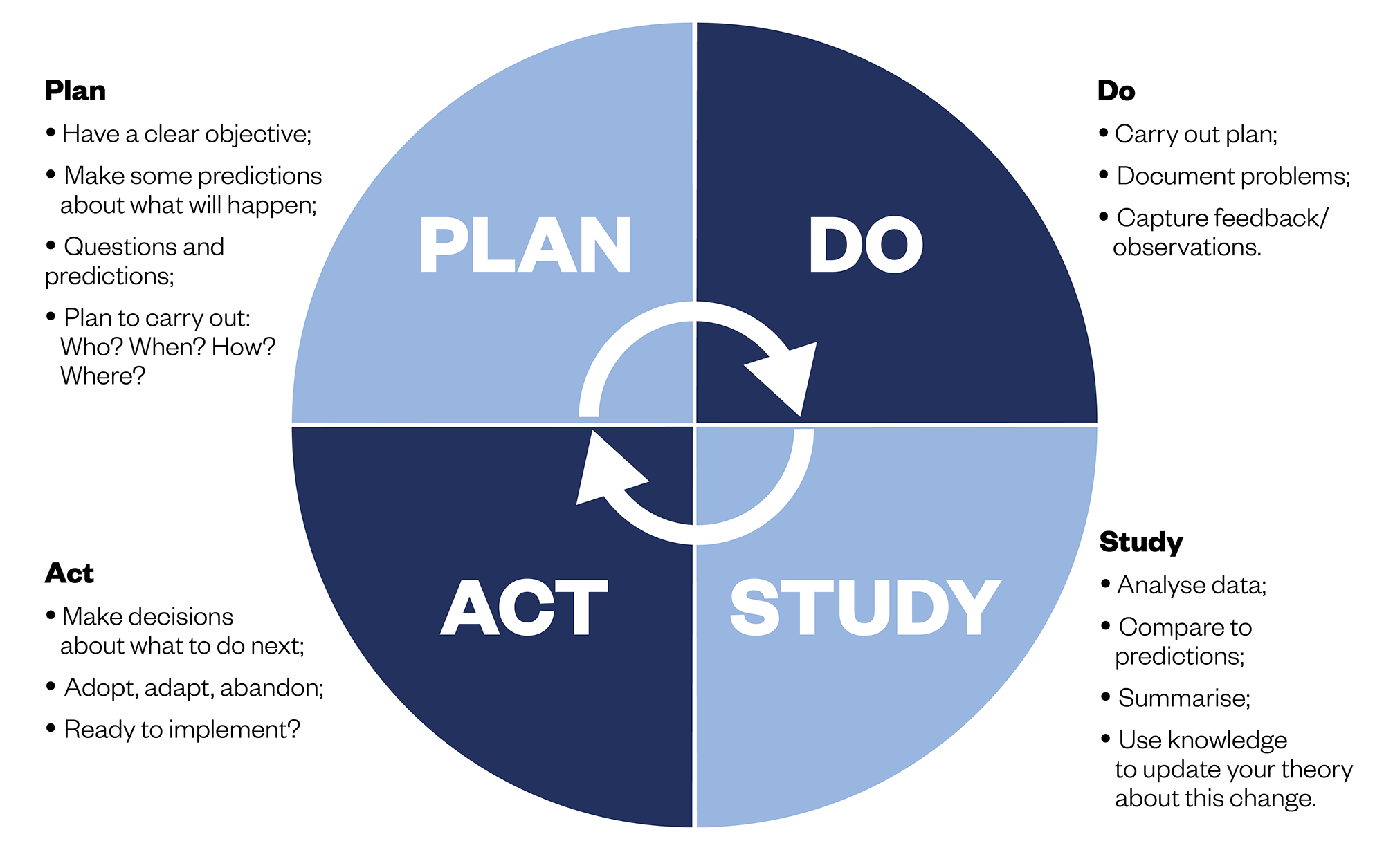

Once these questions are answered, a ‘Plan Do Study Act’ (PDSA) cycle is implemented to test changes in practice (see Figure 2). Using a PDSA cycle allows solutions to be tested on a smaller scale, giving the opportunity to see whether the proposed change will succeed before a full implementation.

Lean

This approach has its origins in the Japanese automotive industry and is based on five core principles[30]:

- Value — understanding value from the patient’s perspective;

- Value streams — identifying all the steps in the pathways of care that patients experience as they move through the system;

- Flow — working along care pathways to align healthcare processes to facilitate the smooth flow of patients and information;

- Pull — creating processes that direct value towards the patient such that every step in the patient journey pulls people, skills, materials, and information towards it, as needed;

- Perfection — an ideal to be pursued through the ongoing continuous improvement of processes.

There is continuous focus on identifying and eliminating waste while keeping the needs of the patient in mind[30,31]. For example, a lean approach to dispensing prescriptions would continually examine the process for the right match between wholesaler ordering and the demand for medicines needed to fulfil prescriptions. This way patients get their medicines on time while the pharmacy avoids inventory waste associated with loss and out-of-date products. For this to be successful, pharmacies must develop a close relationship with patients and other stakeholders involved in the process.

Experience-based co-design

Both users and providers of a healthcare service have valuable and unique insights of their experience. In this approach, data are gathered, for example via interviews and discussions, and patients and healthcare professionals work together to improve care by co-designing services and pathways. The focus is on enhancing the patient experience through a collaborative process[23,32].

Clinical microsystems

Nelson et al. described clinical microsystems as “a small group of people who work together on a regular basis to provide care to a discrete subpopulation of patient”’[33]. An evaluation of QI work with GP practices by Abrahamson et al. described them as distinct clinical units with a designated purpose and function[34]. Clinical microsystems form the building blocks of the entire healthcare system[23,35]. A patient may have interactions with several microsystems and clinical support systems, such as pharmacy medication services[36]. Improvement approaches may focus on quality of care within each microsystem; however, to improve the patient journey, consideration should also be given to the interface between microsystems.

Common QI tools

QI tools are standalone frameworks that can be used as part of the approaches described above. Common tools include:

- Process mapping: studying the processes within a system and how individual steps connect to each other[37];

- Fishbone: assessing the cause-and-effect relationship underpinning a specific problem[38];

- Driver diagrams: examining how unique factors within a system are linked to the outcomes[39];

- Clinical audit: comparing current practice against a standard. The findings can serve as drivers at the primary stage of an improvement project[40].

It is beyond the scope of this article to examine these QI tools in detail but a comprehensive list can be found on the NHS website[41].

Barriers and facilitators of QI

Sustaining continuous QI can be challenging. Changing organisational priorities and the ebb and flow of stakeholder motivation are two commonly experienced barriers. A lack of knowledge about the application of QI at both the top and bottom levels of the organisational hierarchy can inhibit the widespread implementation of QI[20].

There are also factors that have been shown to improve the likelihood of a QI programme being successful.

Systems, capacity and demand

Understanding systems, capacity and demand is an essential prerequisite for effective QI and developing a working knowledge of each will help to reveal both barriers and facilitators.

Pharmacy organisations consist of systems and structures that support the processes involved in providing healthcare services. Examples include ensuring the provision of medicines or medicine related advice to the public, healthcare professionals and other organisations, supporting people in the management of long-term conditions and utilising digital technology to improve access to services.

Capacity refers to a measure of the skill available within the organisation that can be deployed to meet the demand for patient services[23]. Within pharmacies, it is essential to understand the underlying demand for services as well as the nature, level, and quantity of colleague skill sets and the extent to which these influence any detected variations in service provision[42].

Building an effective team

Good leadership and effective communication help to build high-performing teams and encourage early stakeholder engagement. Obtaining different perspectives on a problem and potential solutions is more likely to lead to successful and sustainable QI initiatives[43]. Tools, techniques and theories providing guidance and suggestions to aid the engagement of others at varying stages of a QI initiative can be found on the NHS website[41]. Some of these include:

- Active listening — explaining the value of genuine listening, challenging personal assumptions and the benefits of collaboration;

- Stakeholder involvement — explaining the benefits of stakeholder engagement, how to identify and engage key stakeholders;

- Clinical engagement — explaining why and how to involve senior clinical leaders;

- Commitment, enrolment and compliance — how to identify the current level of support and which stakeholders to focus on;

- Creating a vision — explaining the key characteristics of effective visions;

- Fresh eyes — explaining how you can generate new ideas by involving different perspectives;

- Influence model — setting out the dimensions for supporting leaders to influence others;

- Managing conflict — explaining how to recognise signs of conflict and the approaches that can be taken to manage conflict.

Organisational culture and support

Organisational culture influences all aspects of healthcare quality and safety. Assessing the safety culture of your organisation, for example, may provide an indication of the preparedness of colleagues to engage in improvement projects. Including organisational leadership as part of the improvement team is helpful as they can signpost you to relevant resources, identify the right people to network with and increase buy-in from stakeholders and colleagues[44,45]. There is evidence to suggest that improvement projects that are aligned to organisational strategic objectives are more likely to be successful owing to the support of high-level management and that targeted, well-aligned QI strategies can create a change in organisational culture[46].

Steps into QI

There will be QI opportunities wherever there is an aspect of care delivery that is not working well, or where specific local and national quality indicators are not being met. This can usually be identified from incident reports and other clinical audit results[47]. Patient experience surveys and patient waiting times are typical triggers for starting an improvement project. Patient safety incident reports and ‘near miss’ analysis provide opportunities to set up a QI project (see Box 3). Pharmacies undertake regular clinical audits to understand where service provision does not meet established standards, and these usually point to areas where improvement efforts need to be focused[40].

Box 3: A worked example demonstrating how a project for assuring the safety of patients taking valproate medication may be planned and implemented

Setting: Community pharmacy

Model adopted: ‘Plan Do Study Act’

Issue identified: The use of valproate in pregnancy can lead to up to 40% risk of developmental disorders in babies and up to 10% risk of birth defects[48]. However, awareness among females has been shown to be poor and therefore is an important area for quality improvement[49].

Planning the improvement project

Research and involve the pharmacy team and stakeholders to establish the goal. Quality tools such as process mapping can be used to define the issue. Using the SMART framework (specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and timely), the goal could include:

- Check the existence of a standard operating procedure (SOP) for dispensing of valproate medications, if not this should be developed, and ensure all staff are aware and are trained in how to comply with the valproate dispensing procedure within three months;

- 100% of valproate prescriptions for females should be checked for the presence of a pregnancy prevention programme (PPP) and ensure that there is an effective process for sharing information with GPs when females without a PPP in place are identified.

Establishing baseline data

These can include[50]:

- Outcomes measures: impact on patients’ health and their experiences (i.e. number of patients protected from harm from valproate medication by having a PPP in place);

- Process measures: considers the extent to which necessary processes are in place and the constituent parts of each process works as intended (i.e. existence of an up-to-date SOP);

- Balancing measure: considers if changes or improvements to one part of a complex system cause new problems in other parts (i.e. too complicated SOPs that lead to inefficiency).

Setting up PDSA cycles:

- Plan: the details of the issue identified are discussed with the relevant stakeholders;

- Do: implement and collect data;

- Study: study the findings from the measurement by comparing the data and understanding the extent of the change

- Act: this step requires taking action and deciding whether to implement the change idea or making necessary changes and running the PDSA cycle again using the new parameters

Implementation and dissemination

- A strategy to sustain and spread any improvement gains should be considered at the beginning of the project and fine-tuned after the PDSA tests[51];

- Communication is important to ensure effective dissemination and embedding of improvement ideas.

Ideas for improvement can also come from colleagues within the care pathway. A good starting point is to prioritise areas that have a significant impact on patient care, although consideration should also be given to improving experiences of pharmacy staff and other strategic objectives of the organisation. An important aspect of any QI project is to ensure any governance requirements are met[52]. Contact the appropriate research and development departments within the organisation to find out about any such requirements.

The simplest way to become involved in a QI project is to join an existing initiative. Once the necessary QI skills and knowledge have been developed, it will be possible to identify and lead on a new project. Enthusiasm, optimism, curiosity and perseverance are all essential to engaging in a project and dealing with challenges along the journey[53]. If done well, QI has the potential to drive real change and improve patient outcomes. Being a part of the process can be hugely rewarding for all those involved. As demands and pressures on the NHS and those working within it continue to increase, embedding QI into daily practice will be pivotal to its success.

Useful resources

- Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education (CPPE) e-learning — ‘Quality Improvement: an introduction for pharmacy professionals‘;

- NHS — Quality, service improvement and redesign (QSIR) tools;

- The Centre for Sustainable Healthcare (CSH) — ‘Integrating Sustainability into Quality Improvement‘;

- NHS Education for Scotland (NES) — ‘Quality improvement in primary care: what to do and how to do it‘.

Health inequalities

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s policy on health inequalities was drawn up in January 2023 following a presentation by Michael Marmot, director of the Institute for Health Equity, at the RPS annual conference in November 2022. The presentation highlighted the stark health inequalities across Britain.

While community pharmacies are most frequently located in areas of high deprivation, people living in these areas do not access the full range of services that are available. To mitigate this, the policy calls on pharmacies to not only think about the services it provides but also how it provides them by considering three actions:

- Deepening understanding of health inequalities

- This means developing an insight into the demographics of the population served by pharmacies using population health statistics and by engaging with patients directly through local community or faith groups.

- Understanding and improving pharmacy culture

- This calls on the whole pharmacy team to create a welcoming culture for all patients, empowering them to take an active role in their own care, and improving communication skills within the team and with patients.

- Improving structural barriers

- This calls for improving accessibility of patient information resources and incorporating health inequalities into pharmacy training and education to tackle wider barriers to care.

- 1Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: Executive Summary. UK Government. 2013.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-of-the-mid-staffordshire-nhs-foundation-trust-public-inquiry (accessed Aug 2022).

- 2The NHS Patient Safety Strategy: Safer culture, safer systems, safer patients. NHS England and NHS Improvement. 2019.https://www.england.nhs.uk/patient-safety/the-nhs-patient-safety-strategy/#patient-safety-strategy (accessed Aug 2022).

- 3The NHS Long-Term Plan. NHS. 2019.https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (accessed Aug 2022).

- 4Appleby J, Ham SC, Imison C, et al. Improving NHS productivity: More with the same not more of the same. The King’s Fund. 2010.https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/improving-nhs-productivity (accessed Aug 2022).

- 5Psomas EL, Fotopoulos CV, Kafetzopoulos DP. Core process management practices, quality tools and quality improvement in ISO 9001 certified manufacturing companies. Business Process Management Journal. 2011;17:437–60. doi:10.1108/14637151111136360

- 6Gordon S, Mendenhall P, O’Toole BB. Beyond the checklist: What else health care can learn from aviation teamwork and safety. New York: : Cornell University Press 2012. https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801478291/beyond-the-checklist/#bookTabs=4 (accessed Aug 2022).

- 7High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. UK Department of Health. 2008.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228836/7432.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 8Green AR, Tan-McGrory A, Cervantes MC, et al. Leveraging Quality Improvement to Achieve Equity in Health Care. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2010;36:435–42. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36065-x

- 9Yin XC, Pang M, Law MP, et al. Rising through the pandemic: a scoping review of quality improvement in public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2022;22. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-12631-0

- 10Worsley C, Webb S, Vaux E. Training healthcare professionals in quality improvement. Future Hosp J. 2016;3:207–10. doi:10.7861/futurehosp.3-3-207

- 11Riley WJ, Moran JW, Corso LC, et al. Defining Quality Improvement in Public Health. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2010;16:5–7. doi:10.1097/phh.0b013e3181bedb49

- 12Wolfe A. Institute of Medicine Report: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health Care System for the 21st Century. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice. 2001;2:233–5. doi:10.1177/152715440100200312

- 13Quality in the new health system: maintaining and improving quality from April 2013. UK Department of Health. 2013.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213304/Final-NQB-report-v4-160113.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 14Mohammed K, Nolan MB, Rajjo T, et al. Creating a Patient-Centered Health Care Delivery System. Am J Med Qual. 2014;31:12–21. doi:10.1177/1062860614545124

- 15Pharmacy Quality Scheme: Guidance 2021/22. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Pharmacy-Quality-Scheme-guidance-September-2021-22-Final.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 16Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19. Public Health England. 2020.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908434/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 17Quality standards. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/standards-and-indicators/quality-standards (accessed Jul 2022).

- 18Regulations for service providers and managers. Care Quality Commission. 2022.https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/regulations-enforcement/regulations-service-providers-managers (accessed Aug 2022).

- 19Øvretveit J. Does improving quality save money. A review of evidence of which improvements to quality reduce costs to health service providers. The Health Foundation. 2009.https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/DoesImprovingQualitySaveMoney_Evidence.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 20Riley W, Moran J, Corso L, et al. Defining quality improvement in public health. J Public Health Manag Pract 2010;16:5–7. doi:10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181bedb49

- 21Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is ‘quality improvement’ and how can it transform healthcare? Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2007;16:2–3. doi:10.1136/qshc.2006.022046

- 22Backhouse A, Ogunlayi F. Quality improvement into practice. BMJ. 2020;:m865. doi:10.1136/bmj.m865

- 23Quality Improvement Made Simple: What Everyone Should Know about Healthcare Quality Improvement: Quick Guide. The Health Foundation. 2021.https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2021/QualityImprovementMadeSimple.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 24Dixon-Woods M, Martin GP. Does quality improvement improve quality? Future Hosp J. 2016;3:191–4. doi:10.7861/futurehosp.3-3-191

- 25Weir NM, Newham R, Corcoran ED, et al. Application of process mapping to understand integration of high risk medicine care bundles within community pharmacy practice. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2018;14:944–50. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.11.009

- 26Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/qsir-pdsa-cycles-model-for-improvement.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 27Jamieson T, Armitage G, Anwar N, et al. Improving the safety of medication dispensing in primary care by combining human factors and quality improvement sciences. Improvement Academy. https://improvementacademy.org/documents/Projects/medicines_safety/Pharmacy%20TAPS%20Project%20Report%20v1-2.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 28Moule P, Clompus S, Fieldhouse J, et al. Evaluating the implementation of a quality improvement process in General Practice using a realist evaluation framework. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24:701–7. doi:10.1111/jep.12947

- 29Marvin V, Kuo S, Poots AJ, et al. Applying quality improvement methods to address gaps in medicines reconciliation at transfers of care from an acute UK hospital. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010230. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010230

- 30Going lean in the NHS. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. 2007.https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/Going-Lean-in-the-NHS.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 31Smith I, Hicks C, McGovern T. Adapting Lean methods to facilitate stakeholder engagement and co-design in healthcare. BMJ. 2020;:m35. doi:10.1136/bmj.m35

- 32Bate P, Robert G. Experience-based design: from redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2006;15:307–10. doi:10.1136/qshc.2005.016527

- 33Nelson EC, Batalden PB, Huber TP, et al. Microsystems in Health Care: Part 1. Learning from High-Performing Front-Line Clinical Units. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement. 2002;28:472–93. doi:10.1016/s1070-3241(02)28051-7

- 34Abrahamson V, Jaswal S, Wilson PM. An evaluation of the clinical microsystems approach in general practice quality improvement. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2020;21. doi:10.1017/s1463423620000158

- 35Foster TC, Johnson JK, Nelson EC, et al. Using a Malcolm Baldrige framework to understand high-performing clinical microsystems. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2007;16:334–41. doi:10.1136/qshc.2006.020685

- 36Nelson EC, Godfrey MM, Batalden PB, et al. Clinical Microsystems, Part 1. The Building Blocks of Health Systems. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2008;34:367–78. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34047-1

- 37Improvement Leaders’ Guide: Process mapping, analysis and redesign – General improvement skills. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. 2005.https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/ILG-1.2-Process-Mapping-Analysis-and-Redesign.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 38Online library of Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign tools: Cause and effect (fishbone) . NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/qsir-cause-and-effect-fishbone.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 39Online library of Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign tools: Driver diagrams. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/qsir-driver-diagrams.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 40Foy R, Skrypak M, Alderson S, et al. Revitalising audit and feedback to improve patient care. BMJ. 2020;:m213. doi:10.1136/bmj.m213

- 41Quality, service improvement and redesign (QSIR) tools. NHS England. 2022.https://www.england.nhs.uk/sustainableimprovement/qsir-programme/qsir-tools/ (accessed Aug 2022).

- 42Building capacity and capability for improvement: embedding quality improvement skills in NHS providers. NHS Improvement. 2017.https://qi.elft.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/01-NHS107-Dosing_Document-010917_K_1-1.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 43Using Communications Approaches to Spread Improvement: A Practical Guide to Help You Effectively Communicate and Spread Your Improvement Work. The Health Foundation. 2015.https://www.health.org.uk/publications/using-communications-approaches-to-spread-improvement (accessed Aug 2022).

- 44Mannion R, Davies H. Understanding organisational culture for healthcare quality improvement. BMJ. 2018;:k4907. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4907

- 45Kringos DS, Sunol R, Wagner C, et al. The influence of context on the effectiveness of hospital quality improvement strategies: a review of systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-0906-0

- 46Pannick S, Sevdalis N, Athanasiou T. Beyond clinical engagement: a pragmatic model for quality improvement interventions, aligning clinical and managerial priorities. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;25:716–25. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004453

- 47The Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership: Enabling those who commission, deliver and receive healthcare to measure and improve healthcare services. The Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP). https://www.hqip.org.uk (accessed Aug 2022).

- 48Guidance: Valproate use by women and girls. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2018.https://www.gov.uk/guidance/valproate-use-by-women-and-girls (accessed Aug 2022).

- 49Everything you need to know about sodium valproate and other antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2022. doi:10.1211/pj.2022.1.141709

- 50How to Improve – Science of Improvement: Establishing Measures. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/ScienceofImprovementEstablishingMeasures.aspx (accessed Aug 2022).

- 51Scale-Up and Spread. East London NHS Foundation Trust. https://qi.elft.nhs.uk/collection/scale-up-and-spread/ (accessed Aug 2022).

- 52Guide to managing ethical issues in quality improvement or clinical audit projects. Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership. 2021.https://www.hqip.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Final-2021-Guide-to-managing-ethical-issues-in-QI-and-CA-projects.pdf (accessed Aug 2022).

- 53Jones B, Vaux E, Olsson-Brown A. How to get started in quality improvement. BMJ. 2019;:k5408. doi:10.1136/bmj.k5437