Shutterstock.com

After reading this article you should be able to:

- Describe the types of speech impairments and hearing loss experienced by patients;

- Acknowledge the legal rights of patients with additional speech and hearing needs and ethical practices to provide equitable healthcare delivery;

- Consider the best approaches for tailoring your communication with those with additional speech and hearing needs.

Hearing loss is a prevalent public health issue. The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT) estimates that nearly 20% of the population experiences communication difficulties at some point in their lives1. Data from the Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID), published in 2024, revealed that over 18 million adults in the UK are affected by hearing loss in some capacity — 1.2 million of which experience severe hearing loss and are unable to hear most conversational speech2. Age is a significant factor in developing hearing loss, with 50% of those aged over 55 years and 80% of those aged over 70 years affected2.

If communication is not adapted for patients with additional speech and hearing needs, it can negatively affect their understanding of and involvement in their care3.

Types of speech impairment, hearing loss and the impact on communication

Speech impairments range from fluency disorders (e.g. stuttering) to vocal disorders (e.g. laryngitis) and articulation disorders, which can affect communication in unique ways. For more information on the different types of speech impairment, see Table 14–8.

Patients with communication challenges related to speech are likely to benefit from assessment by a speech and language therapist. They can review the patient’s “current, and likely future, ability to communicate, including their ability to understand, express themselves, retain and recall information, and reason”9.

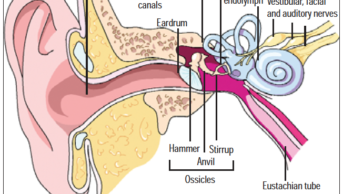

Hearing loss can be categorised into conductive, sensorineural or mixed hearing loss10. These types of hearing loss are usually linked to where in the hearing pathway there is damage, or an issue that is preventing sound from getting to the brain. Whether hearing loss is conductive or sensorineural, it can have wide-ranging impacts, such as struggling to hear conversations, misunderstanding what others say, difficulty to hear over the phone and fatigue11,12.

It is also important for pharmacists to recognise Deaf culture (Box 1) to ensure the delivery of effective patient care. Access to BSL interpreters is a requirement, and making sure information is relayed clearly and effectively will ultimately support better patient outcomes.

Box 1: Deaf culture

Deaf culture in the UK is a diverse community centred around British Sign Language (BSL), shared experiences and a strong sense of identity13. Unlike the traditional medical model that refers to deafness as a condition to be treated, in Deaf culture ‘Deafness’ is viewed as a valid cultural, social and linguistic group14.

Standards and guidance

There is no single guideline for communicating with patients who have additional speech and hearing needs. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provides general advice for ensuring a good experience for adult NHS users15. However, the NHS16 offers specific information on communication difficulties. Charities such as RNID17 and professional bodies such as RCSLT3 also provide practical information. The best source of guidance for an individual patient is the patient themselves and their care records, which should detail communication preferences3.

Ethical and legal considerations

When having consultations with patients who have speech or hearing considerations, pharmacists must adhere to ethical and legal standards to ensure effective communication. The Equality Act 2010 mandates reasonable adjustments, such as sign language interpreters, written materials or assistive listening devices18. This aligns with the Accessible Information Standard, which is a legal requirement for NHS providers to ensure patients receive information in understandable formats and necessary communication support19. The Health and Social Care Act 2012 requires involvement of patients in care decisions, which is achievable only through effective communication20. The General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) standards emphasise person-centred care and effective communication21.

Pharmacists must ensure that their communication methods are adapted to meet the needs of patients with speech and hearing concerns, which upholds the principles of person-centred care and professional integrity. Failure to do so can lead to feelings of isolation and mistrust, ultimately compromising patient care. Failure to comply can lead to isolation, mistrust and compromised care, with significant penalties for non-compliance.

Some patients with speech needs may also have cognitive difficulties, such as dementia, affecting their decision-making capacity9. Others, such as those with motor neurone disease, may have decision-making capacity but struggle to communicate without support9. Misinterpreting communication needs as a lack of capacity can lead to patients being wrongly labelled as incapable9. Some patients may have a relative or other designated person with legal authority to make decisions for them via a lasting power of attorney22. The power of attorney should only be used, however, when the patient is unable to make the decision. It should not be used to avoid adjusting communication methods to enable the patient to make their own decisions.

Best practice for communication in consultations

Patients have different needs, and many know what works best for them. Ask patients what will assist communication or, in hospital or care-home environments, check the patient notes for communication preferences15,17. The basic principles of good communication can help in all interactions16,23:

- Using clear, simple and unambiguous language;

- Speaking slowly and clearly;

- Using body language and gestures to support verbal communication; however, be aware that these may not be understood by all;

- Giving the person time to respond and express their needs.

If the speech difficulties are associated with autism, there can be some additional considerations, such as using more direct language and being mindful of social interaction preferences24.

Where possible, reduce distractions and background noise to help focus communication. This could mean moving to a private area or turning off music in waiting rooms15,17,25. Give your full attention to the patient, which can help you identify whether your communication is effective. In addition, ask questions to clarify understanding and consider alternate phrasing or wording if information is not being understood.

For patients who can lip read, position yourself so that they can see your face clearly, speak normally and do not exaggerate lip movements17. For telephone consultations, first check if the patient needs time to adjust their hearing aid or assistive devices, then speak clearly and do not cover your mouth17. Depending on the environment and situation, reinforce verbal communication with written information, such as text on device screens, pen and paper or whiteboards17. Some video conferencing systems have live captioning that can assist with remote communication.

How to support communication with those with additional speech and hearing needs

Total communication is a “process that ensures that all forms of verbal and non-verbal communication are recognised, valued and actively promoted within an individual’s environment”23. Going beyond verbalisation, gesture, body language, signing and facial expression, total communication includes objects of reference, photographs, drawings, symbols, written words and technology23. An overview of some methods is given below.

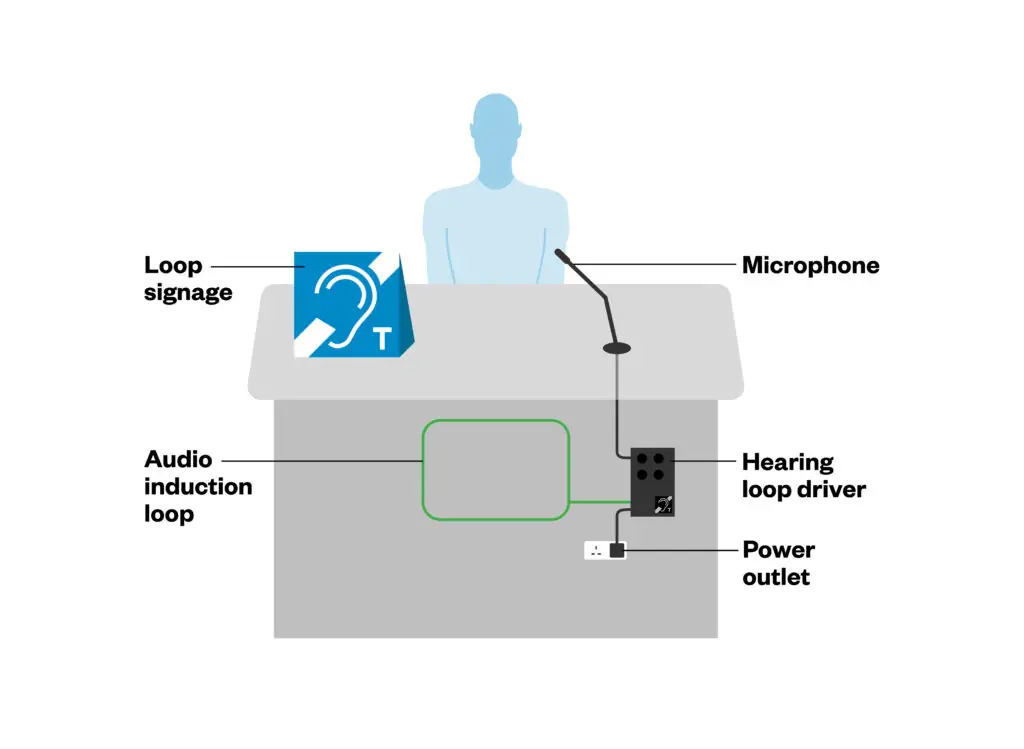

If a loop system is available for use in the clinical area, a sign should be displayed at the patient counter to indicate its availability, and staff should be trained on its use15,25. Those with hearing aids can directly connect to a loop system via a setting on their hearing aid to amplify the sound from the loop microphone26. Patients may benefit from being prompted about using this setting. Figure 1 shows a traditional loop system, but portable systems are also available.

Figure 1: A loop hearing system

Adapted from hearinglink.org

Personal listening devices amplify sound for the user and typically connect to a user’s hearing aid via neck loop, ear hooks or Bluetooth26. A speech-to-text mobile phone application can assist when giving information and can allow the patient to keep a transcript to refer back to27.

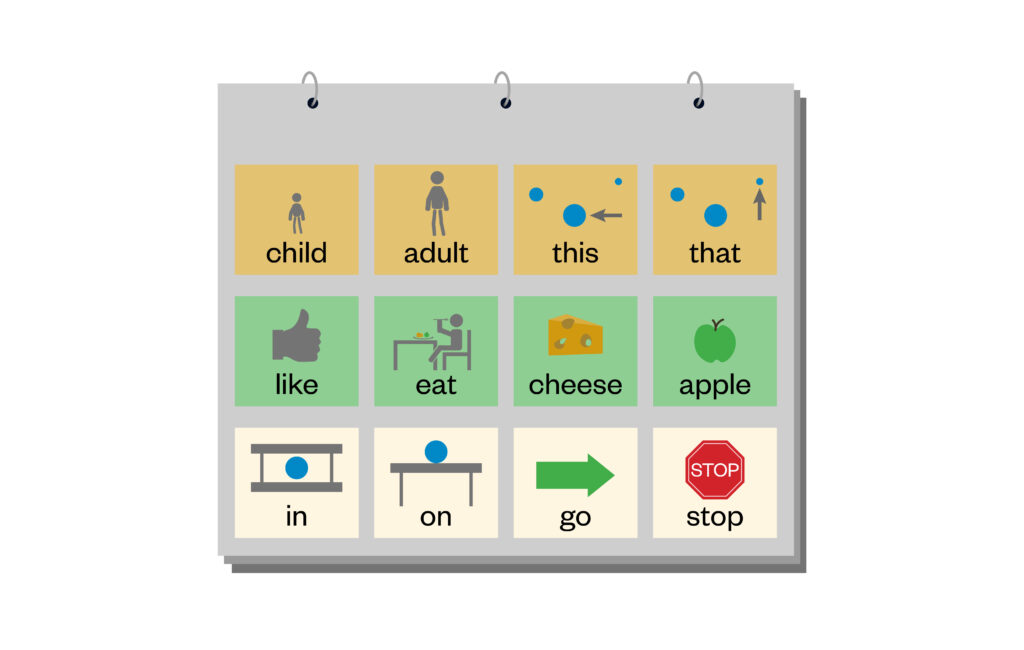

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices can include anything from picture books to personalised technology and are used by patients with complex needs who struggle to communicate by speaking. The Picture Exchange Communication System uses pictures and symbols printed on cards or in a ‘communication book’ that is made personal to them, with items of relevance to them and their life, see Figure 2 28.

Figure 2: Example of a communication book

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Electronic AACs include apps and software on mobile phones, tablets and devices that give a voice output from pressing buttons or using eye tracking28.

Patient representatives can provide valuable information on how a patient best communicates. If communication aids are unavailable, patients may consent to relatives assisting with information and decision-making, such as acting as sign-language interpreters or guides.

Sign-language interpreters are available in inpatient settings to assist with communication. They are regulated by the National Registers of Communication Professionals working with Deaf and Deafblind People29 or the Scottish Association of Sign Language Interpreters30. Sign-language interpreters also hold enhanced disclosure certificates, adhere to their regulator’s code, respect patient confidentiality and remain impartial31. Patients can book interpreters for appointments through services such as Action Deafness32 or access on-demand services through Scope33. Hospital trusts can also book sign-language interpreters for appointments, if given notice by patients. Community pharmacists could ask if the patient would find it helpful to contact an on-demand service prior to any consultations, if there are no arrangements for support from their local health authority.

Box 2: Case study

Mrs JL, a 64-year-old patient with anxiety, hypertension and urticaria, was invited to attend a structured medication review. Recognising that Mrs JL had a hearing loss, she was asked by the pharmacist if she had any preferences for supporting communication in advance of her consultation. Mrs JL stated that she would like to use a transcription app on her phone, but she did not have a hearing aid when asked about the loop system in the pharmacy. The pharmacist booked additional time for the consultation, knowing that rushing would impair communication.

The consultation was conducted in a private room and the pharmacist positioned themselves opposite Mrs JL. The pharmacist asked Mrs JL to bring in her medication from home for the review so it could be used as visual prompts and overcome some of the difficulties of the transcription device recognising drug names. The pharmacist was careful to avoid jargon and medical terms, checked the patient’s understanding at intervals and gave her time to check the transcription on the phone. The pharmacist also checked that the transcription was accurate to ensure it didn’t cause any miscommunication.

The pharmacist was able, in partnership with the patient, to agree on a plan to adequately trial a prescribed emollient, as it was found that Mrs JL had not been using it frequently or as a soap substitute, as initially prescribed. A printed leaflet was provided to Mrs JL on the use of the cream.

Referral flags

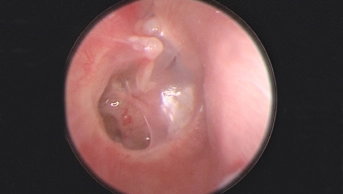

Hearing difficulties can have reversible causes. NICE suggests that for adult patients either presenting for the first time with hearing difficulties or for whom there is a suspicion of hearing difficulties, impacted ear wax and acute infection should be excluded before the patient is referred for an audiological assessment25. Urgent referral is advised for those with sudden or rapid onset of hearing loss25 as follows:

- Refer immediately to an ear, nose and throat service or an emergency department if hearing loss developed suddenly over a period of three days or less within the past 30 days;

- Refer urgently to an ear, nose and throat or audiovestibular medicine service, which should be seen within two weeks, if hearing loss developed suddenly over a period of three days or less and occurred more than 30 days ago, or if the hearing loss worsened rapidly over a period of 4–90 days.

NICE guidance, published in 2018, gives further referral criteria for hearing loss that is associated with additional signs and symptoms (e.g. stroke symptoms; resistant infection associated with discharge in immunocompromised patients; unresolved or recurrent vertigo; persistent tinnitus that is unilateral, pulsatile, has significantly changed in nature or is causing distress; fluctuating hearing loss not associated with an upper respiratory tract infection)25. Urgent referrals to these services can be made by a GP surgery or through NHS 11111.

Although high-street audiology services can assist in some assessment of hearing loss, they cannot always directly refer to the required service and findings need to be presented to a GP or 111 for a referral to be made34. There is regional variation in the arrangements for direct referral to audiology services34.

Conclusion

Pharmacists should adapt their communication styles to support patients with hearing or speech needs. This involves using various methods, such as writing, visual aids or assistive technology, tailored to each patient. Understanding the purpose behind the patient’s communication — whether seeking clarification, expressing concerns or discussing medication — is crucial. By allowing sufficient time and approaching interactions with patience and empathy, pharmacists can ensure patients feel heard and supported. Adapting communication strategies enhances patient experience, improves health outcomes, fosters trust and empowers individuals to manage their health.

Further resources

Information and support for those with communication difficulties or their carers:

- The RNID provides information on assistive devices, benefits and support for patients’ careers and healthcare professionals;

- The ACE Centre supports children with complex physical and communication difficulties and those of any age who need augmentative and alternative communication and assistive technology to communicate;

- The I CAN charity helps children with a communication disability to develop their communication skills;

- Carers Direct helpline can be used by patients or their careers for advice and support including directions to local support. They have a telephone line (0300 123 1053) and textphone or minicom number (0300 123 1004) for those who are deaf, deafblind, hard of hearing or have impaired speech (there is no website);

- SignHealth offers resources including a video library of signed information on medical conditions, first aid and mental health;

- Sign Video is the NHS 111 BSL service accessed via an app;

- Scope has partnered with Sign Solutions to offer BSL interpreters on an on-demand and bookable service.

Information on techniques, assistive devices and applications:

- BSL is the visual language used by deaf people in the UK incorporating hand gestures, finger spelling, lip patterns and facial expressions. RNID provides information and a downloadable fingerspelling card;

- Deafblind Manual, or tactile signing, is where words are spelled out on the individual’s hand. It is used by those who have little or no hearing and sight;

- Makaton is a combination of hand gestures and picture symbols and is used by both adults and children with learning disabilities and communication needs;

- Speech-to-text smartphone applications can convey information that might be difficult to get across by lip reading. The RNID has reviewed seven of the most popular apps available.

This article aims to support the development of knowledge and skills related to the following the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) credentialing areas:

Post-registration foundation pharmacist curriculum

2.1 Keeps the individual at the centre of their approach to care at all times;

2.2 Works in partnership with individuals; viewing each individual receiving care as unique, seeking to understand the physical, psychological and social aspects for that person;

2.4 Engages on an individual basis with the person receiving care, remains open to what an individual might share;

6.2 Assimilates and communicates information clearly and calmly through different mediums, including face to face, written and virtual; tailors messages depending on the audience; is able to respond appropriately to questions;

6.7 Uses appropriate language to engage with the individual; empowers the individual through communication and consultation skills, supporting them in making changes to their health behaviour;

7.6 Treats others as equals, with dignity and respect, supporting them regardless of individual circumstance or background; seeks to promote this.

Core advanced pharmacist curriculum

1.1 Communicates complex, sensitive and/or contentious information effectively with people receiving care and senior decision makers;

1.2 Demonstrates cultural effectiveness through action; values and respects others, creating an inclusive environment in the delivery of care and with colleagues;

1.3 Always keeps the person at the centre of their approach to care when managing challenging situations; empowers individuals and, where necessary, appropriately advocates for those who are unable to effectively advocate for themselves;

2.2 Undertakes a holistic clinical review of individuals with complex needs, using a range of assessment methods, appropriately adapting assessments and communication style based on the individual.

- 1.What are speech, language and communication needs? Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. www.rcslt.org/wp-content/uploads/media/Project/RCSLT/rcslt-communication-needs-factsheet.pdf.

- 2.Prevalence of deafness and hearing loss 2024. Royal National Institute for Deaf People. October 2024. https://rnid.org.uk/get-involved/research-and-policy/facts-and-figures/prevalence-of-deafness-and-hearing-loss/

- 3.Five good communication standards: Reasonable adjustments to communication that individuals with learning disability and/or autism should expect in specialist hospital and residential settings. Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. 2013. www.rcslt.org/wp-content/uploads/media/Project/RCSLT/good-comm-standards.pdf

- 4.Dysarthria (difficulty speaking). NHS. 2023. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dysarthria/

- 5.Stammering. NHS. 2023. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stammering/

- 6.Laryngitis. NHS. 2024. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/laryngitis/

- 7.Barnett N, Parmar P. How to support people with aphasia with medicines optimisation. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2018. https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/how-to-support-people-with-aphasia-with-medicines-optimisation

- 8.Ataxia. NHS. 2021. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/ataxia/

- 9.Speech and language therapists helping to determine mental capacity. Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. www.rcslt.org/wp-content/uploads/media/Project/RCSLT/mental-capacity.pdf

- 10.Types and causes of hearing loss and deafness. Royal National Institute for Deaf People. 2025. https://rnid.org.uk/information-and-support/hearing-loss/.

- 11.Hearing loss. NHS. 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/hearing-loss/

- 12.Holman JA, Drummond A, Hughes SE, Naylor G. Hearing impairment and daily-life fatigue: a qualitative study. International Journal of Audiology. 2019;58(7):408-416. doi:10.1080/14992027.2019.1597284

- 13.What is Deaf culture? British Deaf Association. 2015. https://bda.org.uk/what-is-deaf-culture/

- 14.Becher T, Trowler P. Academic Tribes and Territories : Intellectual Enquiry and the Cultures of Disciplines. 2nd ed. Open University Press; 2001.

- 15.Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg138

- 16.How to care for someone with communication difficulties. NHS. 2024. https://www.nhs.uk/social-care-and-support/practical-tips-if-you-care-for-someone/how-to-care-for-someone-with-communication-difficulties/

- 17.Communication tips for someone with hearing loss . Royal National Institute for Deaf People. https://rnid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/RNID_CommuicationTips_For_PeopleWithHearingLoss.pdf

- 18.Equality Act 2010: guidance. Government Equalities Office, Equality and Human Rights Commission. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-act-2010-guidance.

- 19.Accessible Information Standard. NHS England . http://england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/patient-equalities-programme/equality-frameworks-and-information-standards/accessibleinfo/

- 20.Health and Social Care Act 2012: fact sheets. Department of Health and Social Care. 2012. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-and-social-care-act-2012-fact-sheets

- 21.Standards for pharmacy professionals. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2017. https://assets.pharmacyregulation.org/files/standards_for_pharmacy_professionals_may_2017_0.pdf

- 22.Make, register or end a lasting power of attorney. HM Government. https://www.gov.uk/power-of-attorney

- 23.Inclusive Communication and the Role of Speech and Language Therapy. Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. 2016. https://www.rcslt.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/20162209_InclusiveComms_final.pdf

- 24.Autism and communication. Society NA. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/about-autism/autism-and-communication

- 25.Hearing loss in adults: assessment and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://rnid.org.uk/information-and-support/technology-and-products/

- 26.Technology and assistive devices. Royal National Institute for Deaf People. 2025. https://rnid.org.uk/information-and-support/technology-and-products/.

- 27.Speech-to-text smartphone apps for deaf people and those with hearing loss and tinnitus. Royal National Institute for Deaf People. 2023. https://rnid.org.uk/information-and-support/technology-and-products/speech-to-text-smartphone-apps/.

- 28.Communication aids. Sense. 2023. https://www.sense.org.uk/information-and-advice/technology/communication-aids/

- 29.NRCPD. NRCPD. https://www.nrcpd.org.uk/

- 30.About us. Scottish Register of Language Professionals with the Deaf Community. https://thescottishregister.co.uk/about-us/

- 31.British Sign Language (BSL) interpreters. Royal National Institute for Deaf People. 2023. https://rnid.org.uk/information-and-support/support-for-businesses-and-organisations/communicating-staff-customers-deaf-hearing-loss/british-sign-language-bsl-interpreters/

- 32.Interpreting services. Action Deafness. https://actiondeafness.org.uk/services/interpreting/

- 33.British Sign Language interpreters. Scope. https://www.scope.org.uk/british-sign-language-interpreters

- 34.Onward Referral Guidance. British Academy of Audiology. 2023. https://baaudiology.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Onward-Referral-Guidance-for-Adult-Audiology-Service-Users-Sept-23.pdf.

You might also be interested in…

Managing common ear problems: discharge, ache and dizziness

Managing ear problems: hearing loss and tinnitus