Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, individuals should be able to:

- Understand the long-term goals of asthma management;

- Identify the available pharmacological options and their place in treatment, and how to appropriately advise patients on their use;

- Understand how response to treatment is monitored.

Pharmacological management of asthma is the cornerstone of treatment in children and young people aged 6–17 years. The long-term goals of asthma management, as defined by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), are to achieve good symptom control and minimise future risk of asthma-related mortality and exacerbations[1].

In practical terms, this means achieving asthma control with:

- No daytime symptoms;

- No night-time wakening owing to asthma;

- No need for rescue medications;

- No exacerbations;

- No limitations on activity or exercise[1].

Modifiable factors, such as trigger avoidance, comorbidities, and exposure to air pollution, mould, smoking and vaping in the household, should also be addressed where possible[2]. It is essential that other factors, such as inhaler technique, device suitability and non-adherence, are assessed prior to escalating treatment in uncontrolled patients[2]. This article is the second part of a series on asthma in children and young people; information on the considerations for management of asthma and the role of pharmacy can be found in ‘Children and young people with asthma: symptoms, diagnosis and the role of pharmacy’.

This article will focus on the pharmacological options available to treat children and young people, their indications and any considerations for use in this patient group. In children aged under 6 years experiencing symptoms, the diagnosis is pre-school wheeze. Information on the management of pre-school wheeze, which differs significantly to the management of asthma, can be found in ‘Diagnosis and management of wheeze in pre-school children’.

Management

Pharmacological management of asthma can be achieved using a stepwise strategy. Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network and GINA use a stepwise approach. The guidance from GINA is flexible in that it allows two tracks with different approaches (short-acting beta-agonist [SABA] pathway and SABA-free pathway)[1–3]. A detailed breakdown of the available pharmacological treatment options, their place in therapy and any prescribing considerations can be found in Table 2[1–3].

Short-acting beta agonists

SABAs (salbutamol and terbutaline) have traditionally been the main class of reliever/rescue therapy used for symptoms of wheeze and chest tightness, and remain the choice of treatment in an asthma attack[1,2]. However, monotherapy with SABA is not encouraged in children aged >5 years who have a confirmed diagnosis of asthma, although this is currently being revised in BTS/NICE guidance owing to the association of excessive SABA use with asthma mortality[4–6].

GINA guidelines recommend that an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) is used every time a SABA is used, based on the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) report that demonstrated that, in some patients, treatment with SABA alone was a preventable contributary factor to mortality[5]. GINA guidelines recommend the use of anti-inflammatory reliever therapy with ICS-formoterol, as needed, as a first step in children ≥ 12 years with mild asthma[3,7–9]. NICE guidelines still include monotherapy for a minority of patients with infrequent, short-lived wheeze and normal lung function; however, this is currently under review[2].

Inhaled corticosteroids

ICS are the cornerstone of maintenance therapy and first-line preventer medication, taken daily to control symptoms and prevent exacerbations in children and young people with asthma[1–3].

Choice of ICS includes beclomethasone, fluticasone, budesonide and ciclesonide. These medicines reduce airway inflammation, control symptoms and reduce risk of future exacerbations[10,11]. Efficacy data are largely extrapolated from adolescent and adult studies as there are few trials in children for each medicine; however, limited paediatric clinical trials have demonstrated that ICS are safe and effective in improving asthma control[4,10,11]. Dosing of ICS is described variably in available guidelines, with differing descriptions of dosing. NICE recently published guidance on ICS dosages to support recommendations for children and young people[12]. The guidance outlines ICS dosing in terms of equivalent daily dosing to budesonide as low (≤200 micrograms), moderate (>200–400 micrograms) or high (≥400 micrograms) for children and young people aged 16 years and under. These recommendations currently vary from other published guidelines, such as those from GINA.

It is important to note that response to preventer medications can take up to three months to exert full benefit, particularly in patients who have been undertreated[13].

Long-acting beta agonists

Formoterol, salmeterol, vilanterol and indacaterol are examples of long-acting beta agonists (LABAs) and have a duration of action of at least 12 hours. They are used as add-on therapies in combination with ICS when control is not achieved using ICS alone. LABAs cannot be used as monotherapy as they do not treat airway inflammation and increase the risk of death[14]. They aid control of exercise-induced and night-time symptoms of asthma and have been shown to improve asthma outcomes when added to ICS regimens[15,16].

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

Leukotrienes are mediators involved in the complex inflammatory pathway that contributes to asthma symptoms. They cause bronchoconstriction, an increase in vascular permeability eosinophil recruitment and mucus production. LTRAs block this pathway and have been found to reduce symptoms and improve lung function measurements in patients taking ICS when compared with ICS and placebo[17].

LTRAs are recommended as add-on therapies. NICE guidance recommends a trial of LTRA following trial of ICS and before LABA, based on economic analysis[18]. All other guidelines recommend LABA as the first add-on to ICS treatment[1,3].

In 2019, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency issued a Drug Safety Update to remind prescribers of the risk of neuropsychiatric side effects from LTRAs, such as anxiety, sleep and mood disorders, and suicidal ideation, with a recommendation to advise parents appropriately[19].

Short-acting muscarinic antagonists

Short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMA), such as ipratropium, may sometimes be used as an add-on reliever for moderate-to-severe acute exacerbations of asthma in children with a poor initial response to SABA[1].

ICS/LABA maintenance and reliever therapy and AIR

Maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) is a combination of ICS/LABA, and is recommended in the GINA guidelines as step one of treatment for adults and adolescents aged ≥12 years in place of as needed SABA[7,8,20].

MART regimens in children have also been shown to reduce exacerbations and are included in guidance as a treatment option when asthma is uncontrolled on maintenance ICS/LABA plus SABA (in NICE guidance), or as an alternative to ICS/LABA maintenance or increased dose ICS (in GINA guidance)[21]. MART regimens may be useful in children and young people where adherence to ICS is problematic. Reasons for poor adherence are numerous but may include a dislike of ICS owing to perceived side effects, lack of rapid symptom relief and poor education[22,23]. In the UK, these regimens are licensed from 12 years of age[24].

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists

Tiotropium is a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) that is licensed in children over the age of 6 years as an add-on therapy. Tiotropium has been found to improve lung function and may reduce the risk of severe exacerbations[25]. GINA guidelines include LAMA as a treatment option. Use of LAMA in asthma without additional ICS is associated with an increased risk of exacerbations[26].

Biologics

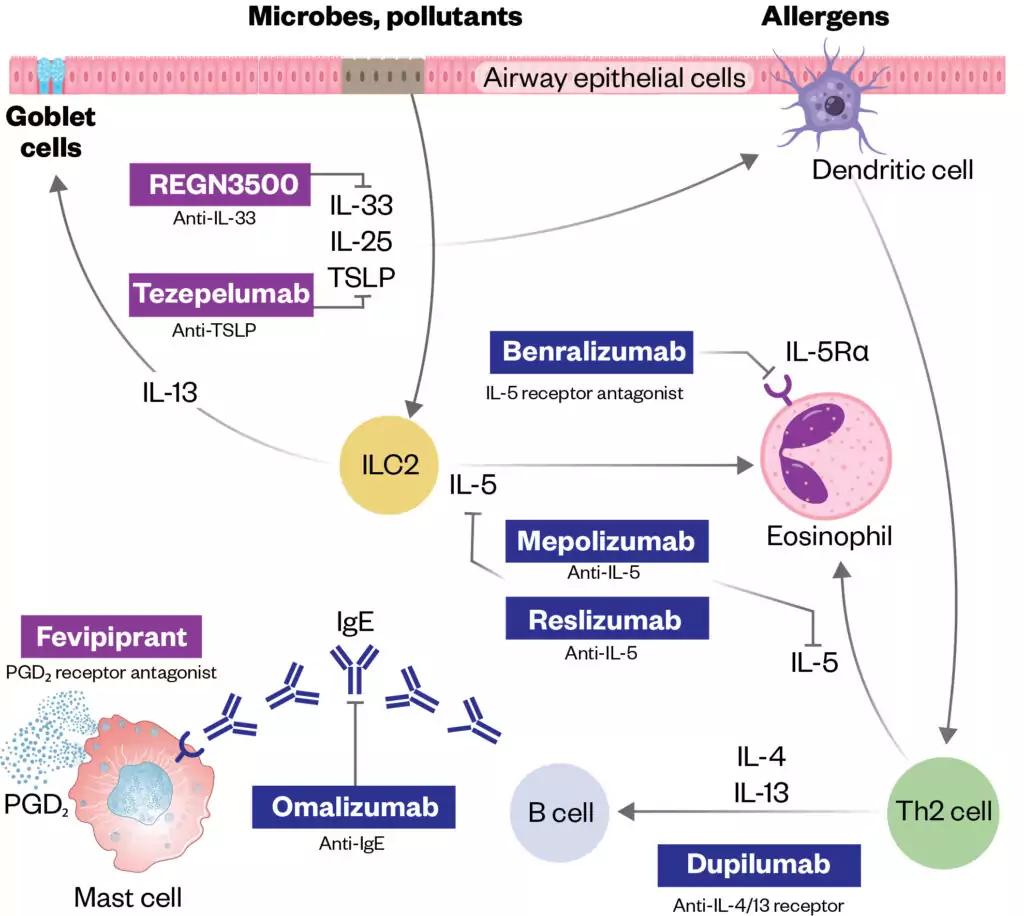

Biologic agents are monoclonal antibodies that effect the allergic pathway, thereby reducing inflammatory biomarkers and cytokines (see Figure). They are used as add-on therapies for children aged 6 years and over who have asthma that is persistently uncontrolled, despite efforts to optimise other pharmacological treatments; other modifiable factors, such as trigger identification and avoidance; and, critically, adherence to standard treatments. The use of biologic agents requires an ongoing commitment to adherence with inhaled therapies and is not an alternative to these therapies[27–30].

Available agents target different pathways in the inflammatory processes (see Figure and Table 2).

The choice of biologic for specific phenotypes of asthma has not been established. Strict criteria, including measurements of blood eosinophils, immunoglobulin E, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO), number of courses of oral corticosteroids and evidence of optimisation of standard therapies, are all required to determine eligibility (see Table 1)[27–30].

The targets of approved add-on biologic treatments (highlighted in dark blue colour) of severe asthma include IgE (omalizumab), IL-5 (mepolizumab and reslizumab), IL-5 receptor (benralizumab), and IL-4/Il-13 receptor complex (dupilumab).

Moreover, experimental drugs (highlighted in purple) such as tezepelumab, REGN3500 and fevpiprant target TSLP, IL-33 and the CRTH2 receptor of PGD₂, respectively.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Monitoring

For those already initiated on treatment, an assessment of symptom control is required to decide if current therapy remains appropriate.

Patients should be regularly reviewed to monitor symptom control, recent exacerbations and risk factors that may require an escalation or allow a step-down of treatment if well controlled.

It is essential that any treatments are reviewed within 6–12 weeks of initiation to ensure they are effective and if any changes are required. In particular, when starting inhaled steroids, a decrease in symptoms would be expected.

Validated questionnaires, such as the children’s asthma control test for children aged 4–11 years or the asthma control test for those aged 12 years and over, should be considered, and used together with a review of lung function, such as peak expiratory flow rate, or, ideally, spirometry and fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) where available[1,2,31]. If no positive changes are seen and adherence is certain, then diagnosis should be questioned.

Summary

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians should understand the vital role of pharmacological management of asthma in the long-term goals of asthma management in children and young people, as well as the place of each drug class in treatment and how treatment response is monitored.

- 1BTS/SIGN British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. British Thoracic Society. 2021.https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/ (accessed Jul 2023).

- 2Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80 (accessed Jul 2023).

- 3Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Global Initiative for Asthma. 2022.www.ginasthma.org (accessed Jul 2023).

- 4Asthma. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/asthma/ (accessed Jul 2023).

- 5Why asthma still kills. Royal College of Physicians. 2015.https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills (accessed Jul 2023).

- 6Suissa S, Ernst P, Benayoun S, et al. Low-Dose Inhaled Corticosteroids and the Prevention of Death from Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:332–6. doi:10.1056/nejm200008033430504

- 7O’Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, et al. Inhaled Combined Budesonide–Formoterol as Needed in Mild Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1865–76. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1715274

- 8Bateman ED, Reddel HK, O’Byrne PM, et al. As-Needed Budesonide–Formoterol versus Maintenance Budesonide in Mild Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1877–87. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1715275

- 9Beasley R, Holliday M, Reddel HK, et al. Controlled Trial of Budesonide–Formoterol as Needed for Mild Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2020–30. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1901963

- 10Nayak A, Lanier R, Weinstein S, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Beclomethasone Dipropionate Extrafine Aerosol in Childhood Asthma. Chest. 2002;122:1956–65. doi:10.1378/chest.122.6.1956

- 11O’Byrne PM, Pedersen S, Lamm CJ, et al. Severe Exacerbations and Decline in Lung Function in Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:19–24. doi:10.1164/rccm.200807-1126oc

- 12Inhaled corticosteroid doses for NICE’s asthma guideline. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80/resources/inhaled-corticosteroid-doses-pdf-4731528781 (accessed Jul 2023).

- 13Sont JK. How do we monitor asthma control? Allergy. 1999;54:68–73. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1999.tb04391.x

- 14Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, et al. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial. Chest. 2006;129:15–26. doi:10.1378/chest.129.1.15

- 15BECKER A, SIMONS F. Formoterol, a new long-acting selective β-adrenergic receptor agonist: Double-blind comparison with salbutamol and placebo in children with asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1989;84:891–5. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(89)90385-0

- 16Bronsky EA, Pearlman DS, Pobiner BF, et al. Prevention of Exercise-induced Bronchospasm in Pediatric Asthma Patients: A Comparison of Two Salmeterol Powder Delivery Devices. Pediatrics. 1999;104:501–6. doi:10.1542/peds.104.3.501

- 17Simons FER, Villa JR, Lee BW, et al. Montelukast added to budesonide in children with persistent asthma: A randomized, double-blind, crossover study. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2001;138:694–8. doi:10.1067/mpd.2001.112899

- 18Chauhan BF, Jeyaraman MM, Singh Mann A, et al. Addition of anti-leukotriene agents to inhaled corticosteroids for adults and adolescents with persistent asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017;2017. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010347.pub2

- 19Dixon EG, Rugg-Gunn CE, Sellick V, et al. Adverse drug reactions of leukotriene receptor antagonists in children with asthma: a systematic review. bmjpo. 2021;5:e001206. doi:10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001206

- 20Bateman ED, O’Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, et al. Positioning As-needed Budesonide–Formoterol for Mild Asthma: Effect of Prestudy Treatment in Pooled Analysis of SYGMA 1 and 2. Annals ATS. 2021;18:2007–17. doi:10.1513/annalsats.202011-1386oc

- 21Bisgaard H, Le Roux P, Bjåmer D, et al. Budesonide/Formoterol Maintenance Plus Reliever Therapy. Chest. 2006;130:1733–43. doi:10.1378/chest.130.6.1733

- 22Sovani MP, Whale CI, Oborne J, et al. Poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids for asthma: can using a single inhaler containing budesonide and formoterol help? Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:37–43. doi:10.3399/bjgp08x263802

- 23Horne R. Compliance, adherence, and concordance: implications for asthma treatment. Chest 2006;130:65S-72S. doi:10.1378/chest.130.1_suppl.65S

- 24Jorup C, Lythgoe D, Bisgaard H. Budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy in adolescent patients with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2018;51:1701688. doi:10.1183/13993003.01688-2017

- 25Kim LHY, Saleh C, Whalen-Browne A, et al. Triple vs Dual Inhaler Therapy and Asthma Outcomes in Moderate to Severe Asthma. JAMA. 2021;325:2466. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7872

- 26Baan EJ, Hoeve CE, De Ridder M, et al. The ALPACA study: (In)Appropriate LAMA prescribing in asthma: A cohort analysis. Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2021;71:102074. doi:10.1016/j.pupt.2021.102074

- 27Mepolizumab for treating severe eosinophilic asthma. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta671 (accessed Jul 2023).

- 28Omalizumab for treating severe persistent allergic asthma. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2013.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta278 (accessed Jul 2023).

- 29Dupilumab for treating severe asthma with type 2 inflammation. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta751 (accessed Jul 2023).

- 30Tezepelumab for treating severe asthma. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta880 (accessed Jul 2023).

- 31Lo D, Beardsmore C, Roland D, et al. Spirometry and FeNO testing for asthma in children in UK primary care: a prospective observational cohort study of feasibility and acceptability. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70:e809–16. doi:10.3399/bjgp20x713033