SOVEREIGN/ISM/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Define and describe the different types of angina;

- List the causes of angina;

- Understand the different diagnostic tools used to diagnose stable angina;

- Describe the management and treatment of stable angina.

Chest pain associated with inadequate blood flow of oxygen to the myocardium owing to progressive narrowing of coronary arteries is known as angina[1]. A common cause of angina is coronary artery disease, which is responsible for 45% of all cardiovascular deaths in the UK[1,2]. Other less common causes include valvular disease (such as aortic stenosis), hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy or hypertensive heart diseases[1].

Around 2 million people in England have experienced angina pain[3]. Data from the 2006 Health Survey for England showed that around 8% of men and 3% of women aged 55–64 years have experienced symptoms of angina. This increases to 14% of men and 8% of women for people aged 65–74 years[3]. As with most long-term conditions, there is a link between increased risk and increasing age[3]. Compared with other cardiovascular diseases, angina also causes disability at a relatively younger age[4].

Angina can be subdivided into[2,5]:

- Stable angina — pain occurring on physical exertion that resolves on rest or with medication;

- Unstable angina — pain occurring at rest and associated with acute coronary syndrome;

- Variant angina — a rare form of angina that can occur at rest because of coronary artery spasms.

Stable angina is associated with a predictable chest pain that is precipitated by activities such as exercise, emotional stress, cold temperatures or heavy meals[1,2,5]. In most cases of stable angina, atherosclerotic plaques remain intact but carry a small risk of plaque rupture. In contrast, unstable angina is caused by ruptured plaques in the coronary arteries or the formation of blood clots that reduce coronary flow through narrowed arteries in the myocardium (see Figure 1)[6]. If left untreated, this can result in a myocardial infarction and is considered a serious condition requiring immediate medical treatment. Variant angina is caused by sudden spasms in coronary arteries resulting in temporary narrowing reducing blood flow to the myocardium and causing severe chest pain.

This CPD module will focus on identification, assessment and management of stable angina, which can have detrimental effects on patient quality of life owing to pain, limited exercise tolerance and poor general health status[4]. It will also describe the integral role of pharmacists working alongside the wider multidisciplinary team in patient management in both primary and secondary care.

Symptoms

Angina is described as a heavy, tight feeling in the front of the chest resulting in constricting discomfort that may radiate to the neck, shoulders, jaw, back or arms. Some patients may present with atypical symptoms, such as gastrointestinal discomfort, breathlessness, fatigue, sweating or nausea[5].

Stable angina is triggered by physical activity because the heart demands more blood supply to the myocardium[1–3]. In a narrowed coronary artery, blood flow is hindered and unable to meet the demands required. The pain is predictable and like any previous events, usually lasts five minutes or less and resolves on rest or after administration of glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) antianginal medication[1–3].

Complications

Stable angina associated with progressive coronary artery disease can lead to further obstruction of coronary blood flow to the myocardium potentially resulting in stroke, myocardial infarction, unstable angina and reduced quality of life[1].

Pharmacists can support patients in preventative management, including the management of modifiable risk factors, medicines education and liaising with the wider multidisciplinary team in primary and/or secondary care. For example, appropriate referral to the GP, assisting transfer of care on discharge from hospital to the community and clarifying details for ongoing management in discharge summaries.

Risk factors and lifestyle advice

The presence of risk factors, such as obesity, increasing age, smoking, poor diet, high cholesterol, hypertension, poor diabetic control and a sedentary lifestyle, can increase the incidence of cardiovascular disease and angina (see Table 1)[1,2,6].

The pharmacy team should use every opportunity to share lifestyle advice with patients who possess modifiable risk factors. For example:

- Encourage patients with a BMI of ≥25 or sedentary lifestyle to increase their physical activity as tolerated, eventually working up to at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity a wee[7,8].

- Offer smoking cessation advice to all smokers and tailor management to the patient and their preferences[9]. A visual guide to help pharmacy teams support individuals to quit smoking can be found here.

- Promote a healthy diet low in saturated fats and salt but high in fibre and omega 3 (e.g. fish such as mackerel and salmon, cod liver oil, wholegrains and beans).

More information around lifestyle advice can be found here.

Assessment

Patients presenting to a community pharmacy with suspected angina should be assessed immediately by a pharmacist in a consultation room. Pharmacists should assess the patient’s physical appearance, vital signs and pattern of angina symptoms. The consultation should aim to identify and exclude serious causes of chest pain that may require immediate medical attention and hospitalisation (e.g. an acute coronary event).

The severity of angina can be graded using the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) class system as follows[10]:

- Class I: Ordinary activity such as walking or climbing stairs does not precipitate angina;

- Class II: Angina precipitated by emotion, cold weather or meals and by walking up stairs;

- Class III: Marked limitations of ordinary physical activity;

- Class IV: Inability to carry out any physical activity without discomfort. Anginal symptoms may be present at rest.

The consultation should include a detailed history of symptoms and the presenting complaint[11]. The following questions should be asked to determine whether the pain is cardiac in nature and warrants medical referral:

- Describe the pain to me;

- Are you currently in pain?;

- Have you experienced any chest pain within the past 12 hours?;

- When do you experience the chest pain?;

- Is the chest pain triggered by activity?;

- How long does it last?;

- Does the pain travel to other parts of the body?;

- Have you tried anything to relieve the pain?;

- Are you experiencing any other symptoms?[11]

SOCRATES is a useful mnemonic that can be used when assessing patients with chest pain (see Box 1)[12].

Box 1: SOCRATES

Site — Where are you experiencing pain?

Onset — When did the pain start?

Character — Describe the pain to me

Radiation — Is the pain spreading to other parts of the body?

Associated symptoms — Please tell me about any other symptoms you’re experiencing

Time course — How long have you been experiencing these symptoms?

Exacerbating / relieving factors — Does anything make the pain better or worse?

Severity — How severe is the pain from 1–10? Where 10 is the worse pain you have ever felt?

In addition to eliciting an accurate history, physical observations such as weight and blood pressure should be taken to determine cardiovascular risk[13]. Monitoring of blood biochemistry, including serum lipid profile and HbA1c to measure diabetes control, is also necessary[14]. Pharmacists should use these results to aid in optimising therapy where possible.

Referral

Patients who are stable but generally present with the following should be referred to their GP for further assessment[13,14]:

- Poor diabetic control: HbA1c of ≥48mmol/L;

- Clinic blood pressure of ≥140/90mmHg; or

- Raised lipids.

- Serum cholesterol >5mmol/L

- HDL cholesterol <1mmol/L

- Non-HDL >4mmol/L, and

- Triglycerides >2.3mmol/L

Patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia should be referred for further assessment. Management targets will differ and should be tailored to patients depending on primary or secondary prevention.

An acute coronary event should be suspected if patients have the following[11]:

- Known coronary artery disease with acute symptoms;

- Clammy and unwell presentation;

- Exertional chest pain that increases with time;

- Heavy tight pressure type pain that radiates to other areas;

- Pain associated with nausea, vomiting and breathlessness.

Chest pain that is persistent and localised is more suggestive of a pulmonary or musculoskeletal cause[2,11]. Acute onset of central chest pain radiating to the patient’s jaw, back, shoulders or arms is highly suggestive of cardiac pain[2,11]. A myocardial infarction should be suspected if the pain lasts longer than 15 minutes and radiates to other areas of the body. Nausea, vomiting, sweating, or feeling breathless is associated with haemodynamic instability (e.g. a systolic blood pressure measuring less than 90mmHg)[2,11].

Pharmacists should call 999 to arrange transfer of the patient to the nearest hospital for further investigation and urgent treatment. If patients are stable and the pain is not severe or cardiac in nature and is relieved on rest or with medication, the patient should be referred for assessment via their GP, NHS 111 or NHS 24 in Scotland.

It is likely that patients will be anxious about their chest pain, particularly if the cause is unknown. It is important that pharmacists acknowledge this and answer any questions patients may have as best as possible. When referral is necessary, the need for further investigation should be explained and discussed with the patient[15].

Investigations and diagnosis

Patients with a blood pressure of >140/90mmHg, heart rate >80 beats per minute and respiratory rate >18 breaths per minute require further investigation and will undergo a number of diagnostic tests (see below) to determine the cause of chest pain and risk of serious cardiovascular events[3,13,14]. These parameters do not indicate a diagnosis of stable angina but will aid further assessment to establish whether the presentation is related to a cardiac event such as stable angina.

Electrocardiogram

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is used to detect abnormalities in cardiac rhythm and support the diagnosis of coronary artery disease[16]. Some changes may include pathological Q waves, left bundle branch block, ST-segment and T-wave abnormalities (see Figure 2) and indicate ischaemia or previous myocardial infarction[17]. However, an ECG is unable to confirm whether chest pain is owing to stable angina. Therefore, a stable angina diagnosis cannot be ruled out based on a normal resting ECG[15].

MAG / Shutterstock.com

Troponin

In stable angina, levels of the cardiac specific enzyme, troponin, are not routinely measured; however, increased levels reflect damage to the heart (e.g. as in MI)[15]. Cardiac biomarker proteins, such as troponin, are released into the bloodstream following injury to the myocardium. Patients undergoing investigation for MI should have their troponin level measured on admission and again 6–12 hours later[16].

Cardiac imaging

Patients usually undergo the following imaging tests, performed by cardiologists, to investigate the nature of the stable angina and other culprit coronary vessels, which may require intervention at a later stage owing to stenosis and patient symptoms.

Images courtesy of Barts Heart Centre

A non-invasive computerised tomography-coronary angiography (CTCA) scan is recommended as a first-line diagnostic tool if ischaemia is suspected following assessment in a chest pain clinic[16]. CTCA allows visualisation of the heart and chest to reveal narrowing of coronary arteries or heart enlargement[15].

If coronary artery disease is suspected or found, then a coronary angiogram can be performed to obtain a detailed look at the coronary arteries and to determine if further intervention with angioplasty is needed[15].

An ECG uses sound waves to produce images of the heart that can be helpful when identifying damaged heart muscle related to poor blood flow[16]. This test can be performed under stress to confirm areas of the heart receiving inadequate supply of blood and is particularly useful in patients with suspected myocardial infarction requiring assessment for heart failure or structural abnormalities[15,16].

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) — also known as the nuclear stress test — examines the coronary arteries and identifies areas of damaged myocardium post MI. If a large area of heart disease is found, interventional cardiologists may consider a coronary angiogram for further investigation and treatment. The MPS test relies on injection of a radioactive substance into the patient’s bloodstream travelling to the heart. A scanner can detect movement of the radioactive material and poor blood flow[15].

The use of CTCA, MPS and ECG tests depends on local availability, expertise in the area and the individual physician’s preference for myocardial assessment[16]. Patient factors to consider include disability, frailty and concerns over the use of pharmacological agents during the tests[16]. Non-invasive functional tests are associated with high accuracy for the detection of flow-limiting coronary stenosis compared with invasive functional testing[16].

Differential diagnoses

The use of cardiac investigations and accurate history usually allows for a straightforward diagnosis of stable angina in most patients. However, chest pain can also be linked with gastrointestinal, thoracic, musculoskeletal and other cardiac causes. Table 2 lists some of the differential diagnoses of angina[18].

Management

The aim of management is to stop or minimise symptoms and to improve the patient’s quality of life and long-term morbidity and mortality[3]. Management options should be discussed with patients and include lifestyle advice, drug treatment and revascularisation techniques using percutaneous or surgical interventions[3]. Figure 3 provides a summary of management for patients with stable angina[19].

Pharmacological therapy

Anti-anginal medicines increase overall coronary blood flow and decrease myocardial oxygen consumption by reducing heart rate, blood pressure and myocardial contractility[20].

Short-acting sublingual glyceryl trinitrate can be used to provide rapid relief of angina symptoms[3]. Following this, optimal medical treatment refers to the use of one or two anti-anginal drugs as necessary, plus secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

The recommended optimal treatment for angina is either a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker[3]. The choice of agent is dependent on the patient’s allergy status, previous intolerances, comorbidities and individual preference. Data from several trials have shown no difference in cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke or death rates between the two treatments[3,21]. If symptoms are poorly controlled on the maximum licensed or tolerated dose of one drug, another drug can be added from a different class[3].

If good control has still not been achieved following treatment with dual therapy, a referral to a cardiologist should be made as there is insufficient evidence to support the use of three or more anti-anginal medicines for the management of stable angina[1,3].

Beta blockers

Multiple beta blockers, including bisoprolol, atenolol and metoprolol, are licensed for use in stable angina and work by blocking the beta-receptors of the sympathetic nervous system. They also confer cardioprotective benefits to patients with left ventricular dysfunction[22]. Standard release metoprolol has a short half-life and is preferred if tolerability needs to be assessed in certain individuals (e.g. patients at risk of bradycardia)[23]. Doses of beta blockers (see Table 3[22,23]) should be titrated according to patient response and heart rate (e.g. increase or withhold if heart rate falls to <60bpm) and should continue to be taken until a cardiology clinic follow-up appointment or until post revascularisation review[3,15].

Side effects associated with beta blocker use include: hypotension, bradycardia, dizziness, headache, syncope, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, sexual dysfunction, coldness of extremities, paraesthesia, numbness (more prevalent in patients with peripheral artery disease), fatigue, sleep disturbance, nightmares. and bronchospasms[22].

Patients with the following should not take beta blockers:

- A history of asthma or bronchospasm;

- Intolerance or hypersensitivity to beta blockers;

- severe or symptomatic bradycardia (heart rate <60 beats per minute);

- Sinoatrial block;

- Second or third-degree heart block;

- Severe or uncontrolled heart failure;

- Hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90mmHg);

- Severe peripheral artery disease;

- Raynaud’s syndrome; or

- Frequent episodes of hypoglycaemia[1,22].

Examples of dialogue that can be used during patient education sessions include[24]:

- “Beta blockers can make you feel dizzy or faint so take care when standing up quickly to reduce your risk of falls”;

- “Your medication can affect your circulation and you might feel the cold in your hands and feet more”;

- “Tiredness, impotence, vivid dreams, and nightmares can occur – speak to your GP if you experience any of these and find them bothersome”;

- “It is important not to stop taking your beta blockers suddenly.”

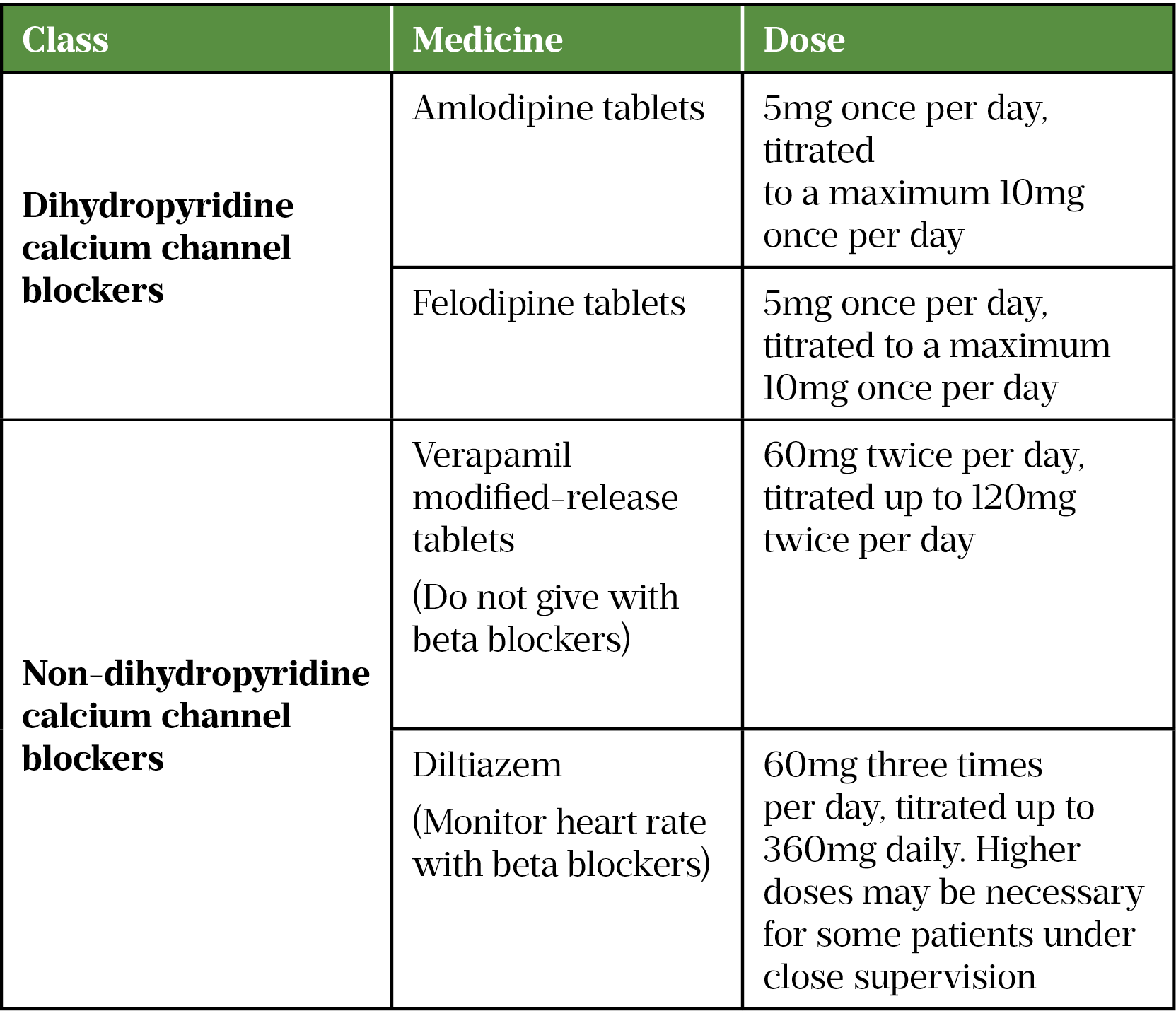

Calcium channel blockers

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) work by inhibiting voltage dependent L-type calcium channels. This reduces intracellular calcium leading to decreased vascular smooth muscle contractility, increased smooth muscle relaxation, and inducing vasodilation[25].

A non-dihydropyridine (rate limiting) CCB, such as diltiazem or verapamil, is preferred over a dihydropyridine CCB (amlodipine or felodipine).

Verapamil and beta blockers must not be given together but it is acceptable to co-prescribe a beta blocker and diltiazem when patients are closely monitored owing to a risk of bradycardia. Rate limiting CCBs are contraindicated in patients with heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction. This is owing to a reduction in myocardial contractility and heart rate[25]. However, if a patient is taking a beta blocker, a dihydropyridine should be prescribed to avoid cardio depression and bradycardia[1,25]. Table 4 summarises dosing recommendations for each CCB[25–28].

Vasodilatory effects such as facial flushing, headaches, postural hypotension and ankle swelling are common with CCBs. Other side effects include dizziness and gastrointestinal disturbances[25].

Contraindications to rate limiting CCBs include severe bradycardia and second- or third-degree heart block. Contraindications to dihydropyridine CCBs include severe hypotension, uncontrolled heart failure and cardiac outflow obstruction (a cardiac defect interfering with the ejection of blood from the chambers of the heart)[1,25].

Examples of dialogue that can be used during patient education sessions include[29]:

- “You have been prescribed a calcium channel blocker for your angina. This is a medicine that can also be used to control high blood pressure”;

- “Calcium channel blockers relax the blood vessels and increase blood flow. You may develop flushing, headaches or feel faint. These effects tend to ease over a few days of taking the medicine”;

- “Mild ankle swelling is common – but be sure to move around and raise your legs frequently when sitting for long periods of time.”

Other pharmacological treatments

If angina symptoms are still poorly controlled following beta blocker and calcium channel blocker monotherapy/dual therapy, consider a nitrate, ranolazine, ivabradine or nicorandil as an adjunct.

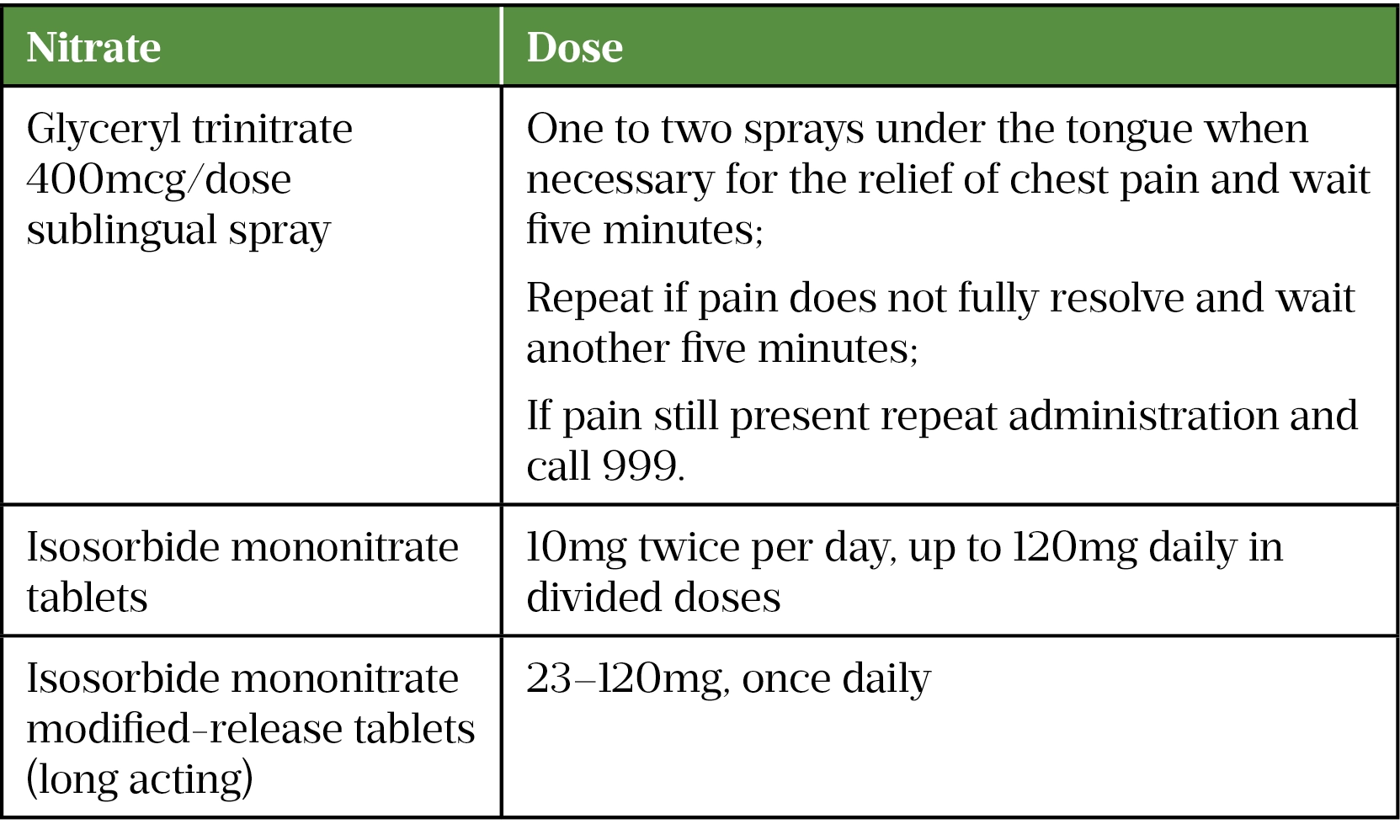

Nitrates

Nitric oxide is primarily produced by vascular endothelial cells that cause vasodilation. The nitrate class of drugs act directly on the vascular smooth muscle to cause relaxation and are known as vasodilators. Nitrates can reduce preload and afterload and reduce overall oxygen demand[1,30].

Nitrates are available in a variety of formulations, including a short acting sublingual spray to be used as required and isosorbide mononitrate (ISMN) standard and modified release tablets for maintenance therapy[31]. There is little evidence to show any clear benefits between the use of modified release (MR) and immediate release preparations, however, to improve compliance the MR formulation may be favourable[32]. Nitrate dosing information is summarised in Table 5[31,33].

Common nitrate side effects include transient hypotension, headache, burning, stinging, or tingling of the mouth, especially with sublingual formulations[33].

Patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, aortic/mitral valve stenosis or diseases associated with a raised intracranial pressure including cerebral haemorrhage should not take nitrates[31,33].

Examples of dialogue that can be used during patient education sessions include[34]:

- “Use your GTN spray under the tongue whenever you feel chest pain. It is important to follow the instructions carefully” (see Table 5 for dose and administration instructions);

- “Avoid medicines such as sildenafil or similar used for erectile dysfunction when taking nitrates for stable angina. Taking these together can cause a sudden drop in your blood pressure which can be dangerous.”

Some degree of tolerance is observed following chronic use of nitrates. To help protect against ischaemia while avoiding the development of tolerance, a dosing strategy should be used to include an 10–14 hour nitrate-free period. This is especially important in patients taking immediate release tablets twice a day.

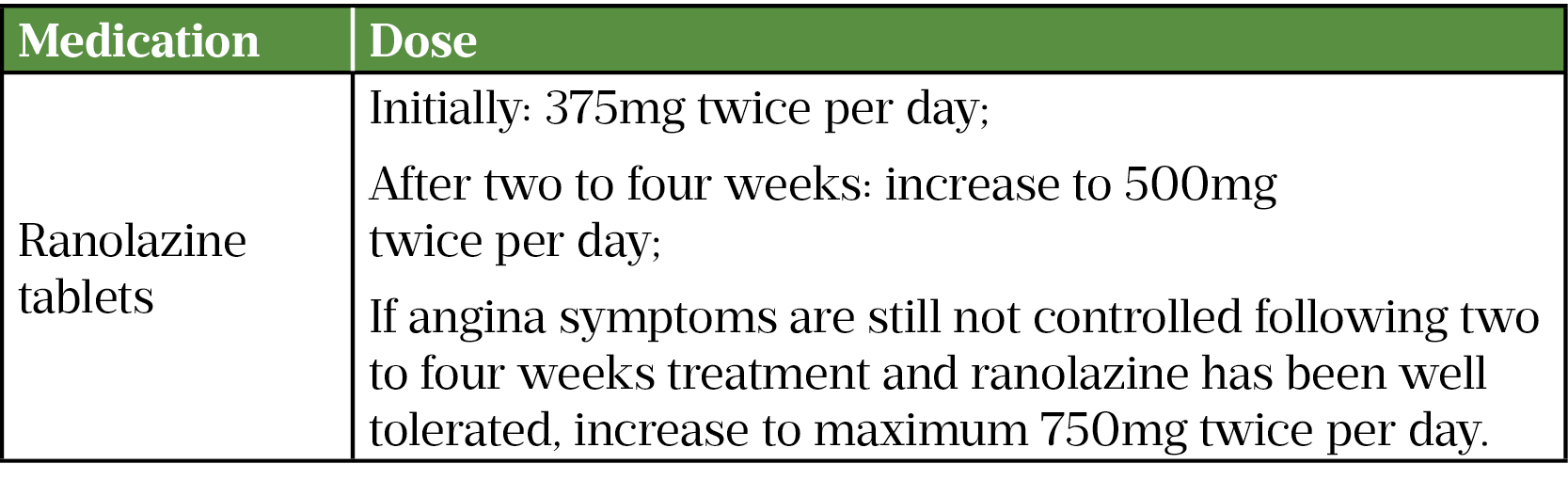

Ranolazine

Calcium overload in ischaemia causes impaired relaxation and increases ventricular diastolic wall stress and end diastolic pressure impairing overall blood flow through the coronary arteries[35]. Ranolazine blocks the late inward sodium currents in cardiomyocytes. Calcium overload and diastolic wall stress is reduced leading to improved coronary blood flow[35]. It is a good option for patients with generally low blood pressure but doses (see Table 6[35]) should be titrated carefully in patients who weigh <60kg. Low-weight patients should be initiated with 375mg twice a day and titration should be exercised with caution owing to the higher incidence of side effects in patients with low body weight[30]. Ranolazine should be initiated and reviewed by a cardiologist to assess response and if no symptomatic benefits are experienced then treatment should be reviewed and stopped[35].

Side effects of ranolazine can include dizziness, headaches, nausea, vomiting, asthenia, constipation and prolonged corrected QT interval (QTc)[35].

Patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30mL/min) or moderate or severe hepatic impairment, or who are pregnant or breastfeeding, should not take ranzolazine[35].

Examples of dialogue that can be used during patient education sessions include[35]:

- “You may experience headaches, feeling faint or dizziness when starting ranolazine. These are common side effects and should resolve after a few days”;

- “It is important to tell your cardiologist or GP if your angina symptoms do not improve while taking this medicine.”

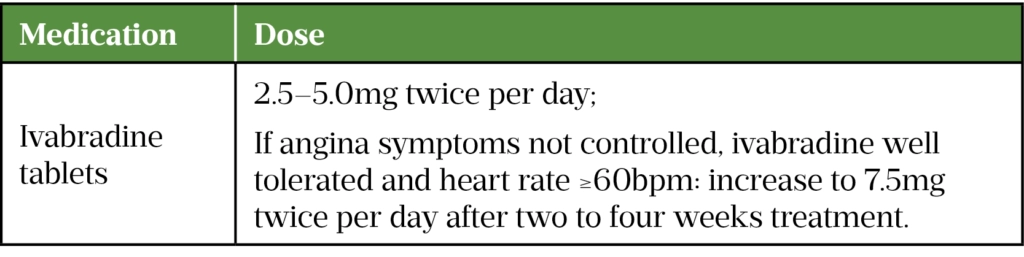

Ivabradine

Ivabradine selectively inhibits the pacemaker If current in a dose-dependent manner. The If current is also known as the ‘funny current’, which is responsible for generating spontaneous activity and controls the heart rate by acting specifically on the cardiac rate and rhythm control. Inhibiting this channel reduces cardiac pacemaker activity, selectively slowing the heart rate and allowing more time for blood to flow to the myocardium[1]. Ivabradine should therefore only be initiated in patients with normal sinus rhythm at doses recommended in Table 7[36]. Heart rate should be checked regularly to ensure patients maintain ≥60bpm[36].

Side effects affecting vision are common, including blurred vision and luminous phenomena (brief spots/flashes of light). Bradycardia, headaches and gastrointestinal disturbances have also been reported[36].

Contraindications include acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina, severe hypotension (blood pressure less than 90/50mmHg), sino-atrial block or third degree AV block, severe hepatic insufficiency, unstable heart failure, pregnancy, breastfeeding and patients who are concomitantly taking rate limiting calcium channel blockers[36].

Examples of dialogue that can be used during patient education sessions include[37]:

- “Ivabradine can cause your heart rate to slow. It is important that it is checked regularly to ensure it stays at 60 beats per minute or more”;

- “You may experience difficulties with changes in light and blurred vision. This is a common side effect. Do not drive, especially at night, until you know how you react to this effect.”

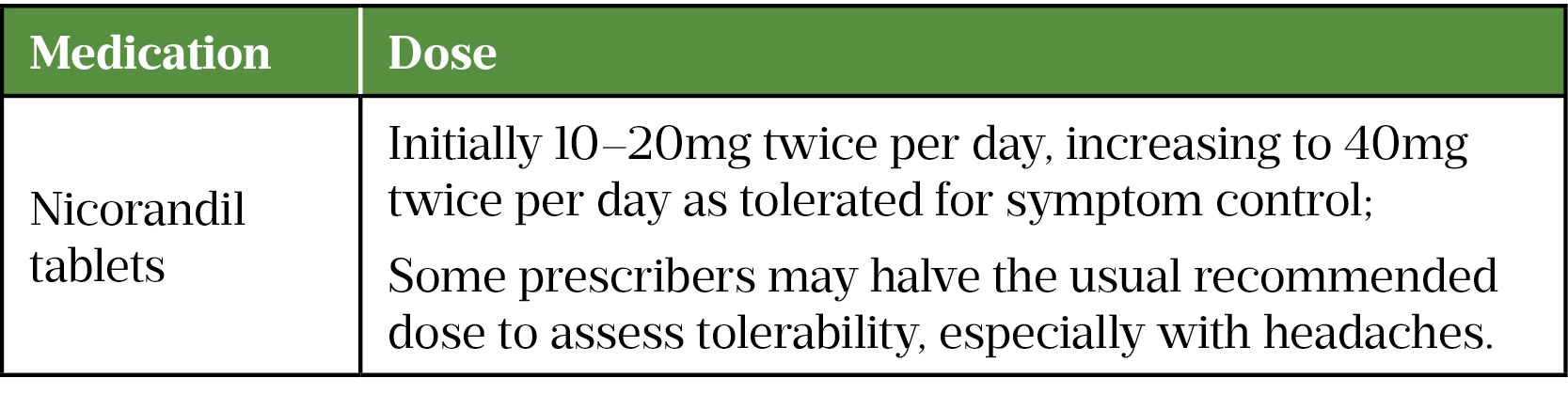

Nicorandil

Nicorandil is a vasorelaxant that has a nitrate group attached to its chemical structure. This reduces preload by acting directly on systemic venous vessels and dilates epicardial coronary arteries[1,38]. The recommended dose of nicorandil can be found in Table 8[39].

Side effects of nicorandil include headache, dizziness, tachycardia, flushing, nausea, vomiting and serious skin, mucosal, eye and gastrointestinal ulcers, which may progress to perforation. Medicines such as sildenafil or similar used for erectile dysfunction should be avoided when using nicorandil for stable angina owing to sudden drop in blood pressure, which can be dangerous[39].

Patients in cardiogenic shock, or who have severe hypotension, left ventricular failure, hypovolaemia or acute pulmonary oedema should not take nicorandil[39].

Examples of dialogue that can be used during patient education sessions include[39]:

- “You might experience side effects such as headaches or dizziness. These are common and should settle after a few days.”

Secondary prevention

Patients requiring symptom control and prevention of coronary artery disease progression require secondary prevention with:

- Aspirin 75mg once daily[40];

- Atorvastatin 40–80mg daily (or a similar high-dose statin for low density lipoprotein [LDL] reduction)[41];

- An angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker[3,16].

Clopidogrel can also be used in patient’s intolerant to aspirin, but consideration of gastrointestinal bleeding needs to be made[40]. This is important as it will help reduce cardiovascular events such as a myocardial infarction or stroke. Angina occurs because of coronary artery disease, which limits the blood flow to the myocardium, if left untreated the progression can lead to complications, such as a myocardial infarction and ischaemia resulting in myocardial injury[3,15,16]. Patients can be offered a proton pump inhibitor (e.g. lansoprazole capsules 30mg once a day) to take with/after meals to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding/intolerance[42].

Revascularisation

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) are revascularisation strategies offered to patients who have poorly controlled stable angina symptoms despite optimal medical treatment[3]. One type of PCI uses a catheter insertion with a balloon and drug eluting stent (DES) into the coronary arteries where blood flow is limited owing to narrowing. A DES is inserted via dilatation of the balloon, other approaches involve percutaneous old balloon angioplasty — using a balloon to open the obstructed coronary artery restoring blood flow[16].

CABG is a surgical opening of the chest using graft techniques to bypass the occluded sections of coronary flow[3,15,16].

Summary

Appropriate management of stable angina symptoms relies on optimal medical management. Pharmacists are able to mitigate the development of serious complications by educating patients about their medicines and providing advice about symptom control.

Additional resources

- 1Angina – Causes, symptoms and treatments. British Heart Foundation. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/conditions/angina (accessed Nov 2021).

- 2Angina. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/angina/ (accessed Nov 2021).

- 3Stable angina: management Clinical guideline [CG126]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2011.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg126 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 4Angina. Mayo Clinic. 2020.https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/angina/symptoms-causes/syc-20369373 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 5Tendera M, Chassany O, Ferrari R, et al. Quality of Life With Ivabradine in Patients With Angina Pectoris. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:31–8. doi:10.1161/circoutcomes.115.002091

- 6Angina. Heart Foundation New Zealand. https://www.heartfoundation.org.nz/your-heart/heart-conditions/angina (accessed Nov 2021).

- 7Start losing weight. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/healthy-weight/start-losing-weight/ (accessed Dec 2021).

- 8Exercise. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise (accessed Nov 2021).

- 9Stop smoking treatments. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stop-smoking-treatments (accessed Nov 2021).

- 10SIGN 151 — Management of stable angina. A national clinical guideline. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2018.https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1088/sign151.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 11What are the red flags for chest pain? . British Journal of Family Medicine. 2019.https://www.bjfm.co.uk/blog/what-are-the-red-flags-for-chest-pain (accessed Nov 2021).

- 12Pandie S, Hellenberg D, Hellig F, et al. Approach to chest pain and acute myocardial infarction. S Afr Med J. 2015;106:239. doi:10.7196/samj.2016.v106i3.10323

- 13Blood pressure test . NHS. 2018.http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/blood-pressure-test (accessed Nov 2021).

- 14Guide to HbA1c. Diabetes.co.uk. 2019.https://www.diabetes.co.uk/what-is-hba1c.html (accessed Nov 2021).

- 15Recent-onset chest pain of suspected cardiac origin: assessment and diagnosis. Clinical guideline [CG95]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2010.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg95 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 16Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. European Heart Journal. 2019;41:407–77. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425

- 17Klabunde RE. Electrophysiological Changes During Cardiac Ischemia. Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts. 2016.https://www.cvphysiology.com/CAD/CAD012 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 18Boudonas G. β-Blockers in coronary artery disease management. Hippokratia 2010;14:231–5.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21311628

- 19Pathways – Managing Stable Angina. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/chest-pain/managing-stable-angina (accessed Nov 2021).

- 20Klabunde RE. Antianginal Drugs. Cardiovascular Pharmacology Concepts. 2007.https://www.cvpharmacology.com/Angina/antianginal (accessed Nov 2021).

- 21Harskamp RE, Laeven SC, Himmelreich JC, et al. Chest pain in general practice: a systematic review of prediction rules. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027081. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027081

- 22Bisoprolol 2.5mg film coated tablet. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6126/smpc#gref (accessed Nov 2021).

- 23Metoprolol Tartrate 50 mg tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5345/smpc#gref (accessed Nov 2021).

- 24Rull G. Beta blockers – Uses and side effects. Patient.info. 2018.https://patient.info/heart-health/beta-blockers (accessed Nov 2021).

- 25Amlodipine 5 mg tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6075/smpc (accessed Nov 2021).

- 26Felodipine tablets 5mg. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5884/smpc#gref (accessed Nov 2021).

- 27Verapamil SR tablets 5mg. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10613/smpc (accessed Nov 2021).

- 28Diltiazem tablets 5mg. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8008/smpc (accessed Nov 2021).

- 29Payne J. Calcium-channel Blockers. Patient.info. 2019.https://patient.info/heart-health/calcium-channel-blockers-leaflet (accessed Nov 2021).

- 30Klabunde RE. Nitrodilators. Cardiovascular Pharmacology Concepts. 2012.https://cvpharmacology.com/vasodilator/nitro (accessed Nov 2021).

- 31Monomil XL 60mg tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/549 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 32Angina: Nitrates. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/angina/prescribing-information/nitrates (accessed Nov 2021).

- 33Isosorbide Mononitrate tablets 10mg. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11208/smpc (accessed Nov 2021).

- 34Nitrate Medication. Patient.info. 2017.https://patient.info/heart-health/nitrate-medication (accessed Nov 2021).

- 35Ranolazine prolonged release tablets 375mg. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6442/smpc (accessed Nov 2021).

- 36Ivabradine film coated tablets 2.5mg. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11036/smpc (accessed Nov 2021).

- 37Allen H. Ivabradine tablets, Procoralan. Patient.info. 2019.https://patient.info/medicine/ivabradine-tablets-procoralan (accessed Nov 2021).

- 38Simmons MA. Nicorandil. Science Direct. 2007.https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/nicorandil (accessed Nov 2021).

- 39Nicorandil tablets 10mg. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/652/smpc (accessed Nov 2021).

- 40Aspirin tablets 75mg. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2408/smpc (accessed Nov 2021).

- 41Atorvastatin tablets 40mg. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5275/smpc (accessed Nov 2021).

- 42Lansoprazole GR capsules 30mg. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4761/smpc (accessed Nov 2021).

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I really enjoyed reeding the topic.

Thank you very much.