Mclean/Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Give an overview of educational supervision;

- Explain what skills are needed to be an effective educational supervisor;

- Understand how effective supervision can support pharmacists.

Workplace learning has formed part of preregistration training (now foundation training) for many years, and supervision of this is becoming more embedded into pharmacy education and development — both at foundation and advanced level. Effective supervision in pharmacy has been shown to improve the ability of trainees to manage challenges in the workplace and develop their roles[1]. It is important that pharmacists and pharmacy professionals develop the right knowledge and skills to effectively support and supervise trainees. Being a supervisor is very rewarding and provides an excellent opportunity for both personal and professional development.

This article will explain the different supervisor roles within pharmacy and the skills needed to be an effective supervisor.

Supervisor roles within pharmacy

Supervision is a process of professional learning and development that enables trainees to reflect on and develop their knowledge, skills and competence through agreed, regular support with another professional. Supervision has been defined as “the provision of guidance and feedback on matters of personal, professional and educational development in the context of a trainee’s experience of providing safe and appropriate patient care”[2]. Mentoring has also been described as providing guidance and support[3]. A supervisor can also be a mentor, but the element of assessment within the supervisor role can mean it is better, where possible, to have an independent mentor who does not have line management responsibilities for the trainee.

The quality of the relationship between supervisor and trainee is an important factor for effective supervision[2]. This involves both the supervisor and trainee being committed to teaching and learning, and having the appropriate attitudes and interpersonal skills. In addition to clinical competence, there are certain behaviours and interpersonal skills required to be an effective supervisor and these are listed in Box 1[2].

Box 1: Behaviours and interpersonal skills required for supervisors

- Providing direct guidance;

- Linking theory and practice;

- Being a role model;

- Involving trainees in patient care;

- Active listening;

- Negotiation skills;

- Assertiveness;

- Counselling skills;

- Being supportive;

- Providing timely, effective feedback;

- Self-awareness;

- Respect for others;

- Empathy;

- Being positive;

- Being enthusiastic;

- Appraisal skills.

There is a variety of supervisor roles within pharmacy designed to support learners at different stages of their training. They can be broadly classed as either educational or practice-based.

Educational supervisor roles

An educational supervisor in pharmacy has responsibility for a trainee’s educational progress during a series of training placements or an entire programme[4]. Some examples of educational supervisor roles in pharmacy are listed in Box 2.

Box 2: Examples of educational supervisor roles within pharmacy

- Designated supervisor

- Post-registration foundation educational supervisor

- Designated prescribing practitioner

- National Vocational Qualification internal assessor

Educational supervisors should have a thorough understanding of the programme’s learning outcomes and facilitate a range of learning, assessment and support opportunities in the workplace to meet these. An educational supervisor will support the trainee in developing objectives and action plans that are individual to them at the outset. The supervisor will then meet regularly with the trainee to help them evaluate their progress towards meeting their objectives and set further objectives, as required, until all learning outcomes for the programme have been met. An educational supervisor’s role may also involve liaising with any practice-based supervisors who also have responsibility for the trainee.

Practice-based supervisor roles

A practice-based supervisor is responsible for the day-to-day supervision of pharmacists in the workplace[5]. Practice-based supervisors facilitate learning in the workplace by working with the trainee pharmacist to identify learning opportunities, assess the trainee, provide feedback on performance and identify any difficulties. However, the overall responsibility of supervising the trainee pharmacist, reviewing the trainees’ progress and portfolio and signing them off sits with the educational supervisor. It may be that the educational supervisor for a trainee is also the practice-based supervisor, depending on the workplace structure.

Coaching

Coaching has been defined as “unlocking a person’s potential to maximise their own performance”[4]. It is an essential element of good supervision. There is a need to ensure safe practice in pharmacy, meaning that coaching in pharmacy education must include some guidance for trainees, as well as supporting independent development and the ability to self-assess[6]. Finding their own answers through coaching helps the trainee to build self-belief.

To coach successfully, there must be a trusting relationship between the coach and trainee. Remaining calm, listening actively and having a supportive and non-threatening environment helps to establish a trusting relationship[7,8].

Essential communication skills for coaching include powerful questioning, active listening and awareness[4]. A trainee cannot change what they are not aware of — this is known as ‘unconscious incompetence’[9]. It is the coach’s role to raise awareness in the trainee through powerful questioning. Questions beginning with ‘what, when, who, how much and how many’ focus attention and help the trainee develop self-motivation[4]. The coach should avoid the use of ‘why’, as this can imply criticism. By asking broad, open questions first and then focusing on the detail, the coach encourages the trainee to develop. The coach must engage in active listening to know what question to ask next. Active listening includes listening for emotion in the voice, watching body language and listening to the words[4].

A supervisor new to the role may find coaching daunting. The use of a coaching model, as a structure to work within, can be helpful. Models include the 3-D Technique, the Practice Spiral Model and the GROW Model[8]. Coaching skills require practice and are not necessarily intuitive, so training may be necessary.

A barrier to coaching is a lack of belief in the process by the trainee[6]. To help reduce this barrier, it is important that the trainee has an expectation of feedback and is open to receiving it. This requires education of all participants to ensure they are fully aware of the expectations.

Assessment tools

Assessment in the workplace is critical to determining trainee readiness to provide safe, effective and efficient patient care[10]. Workplace-based assessments (WBAs) have been used in workplace training across other healthcare professions for many years; however, in 2011, the General Medical Council recommended that WBA activities with a focus on assessment for learning be termed ‘supervised learning events’ (SLEs) and WBAs with summative consequences be called ‘assessment of performance’[11]. This rebranding was to emphasise that WBAs should provide a structured and supportive approach to training, rather than be onerous, excessive, ‘tick-box’ exercises to achieve programme requirements[12].

SLEs provide a learning opportunity, where the benefit comes from reflection upon developmental feedback provided by the supervisor. The feedback should be specific, highlighting what the trainee has done well and areas that require improvement[13]. The feedback should then feed into the trainees’ action plan to enable continued development.

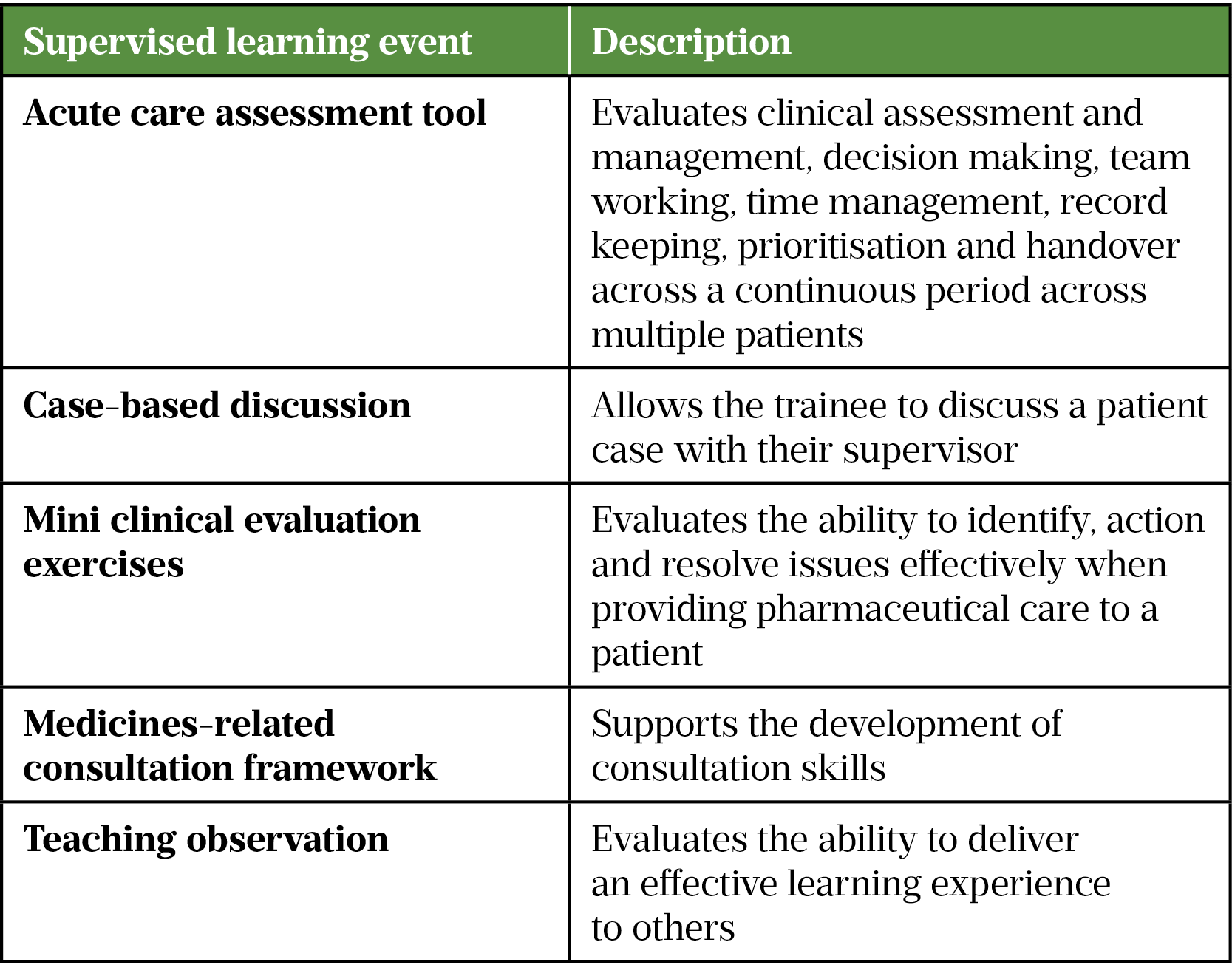

SLEs have been used in some preregistration and postgraduate programmes for some time. They are now becoming more embedded into foundation and early careers programmes (see Table for examples of SLEs used in pharmacy practice)[14,15].

Feedback

The ability to give constructive feedback is an essential skill for any supervisor. Feedback is the process of providing information to a trainee with the aim of ‘narrowing the gap between actual and desired performance’[16]. Constructive feedback can raise a trainee’s self-awareness and help them to achieve their potential[17]. Not giving feedback, however, can encourage poor performance as the trainee is unaware of areas that need to be improved[18]. This can put patients at risk of harm. Not giving feedback also means good performance is not encouraged, which could lead to a lack of motivation and job satisfaction.

To avoid judgemental feedback, it is necessary to learn constructive ways in which to give feedback. Trainees may be defensive to feedback[17]. Ensuring feedback is routine within the organisational culture will help to overcome this, as it will seem less personal.

Valuable feedback is regular, timely and non-judgemental[9,18–21]. It should encourage reflection and there should also be a good rapport between the supervisor and trainee.

Models of how to deliver feedback include the feedback sandwich, the reflective feedback conversation and the Pendleton model[16,22,23].

- Feedback sandwich: the trainee is first given positive feedback, then there is a focus on areas for improvement and finally the interaction ends on a positive note. A disadvantage of this model is the tendency for the trainee and supervisor to focus on the positive aspects;

- Reflective feedback conversation: the trainee is encouraged to reflect on their own performance and identify what could be improved. A disadvantage of this method is the lack of feedback on what went well;

- Pendleton model: this involves a structured conversation, in which the trainee’s comments are followed by the teacher’s comments, focusing on the positive first; for example, asking the trainee ‘What do you think went well?’ and then ‘What do you think could be improved?’. The advantage of this model is that it encourages the trainee to assess their own performance. It also allows time to discuss both the positives and what can be improved.

The challenge in using these models is to find one that works for the supervisor and the trainee in any given situation. The supervisor must be aware of the models in the first place and know which to use in each situation. To do this, the supervisor must practice using the different feedback models and reflect to acquire, maintain and develop the skill of delivering effective feedback.

Supporting trainees in difficulty

Sometimes trainees have difficulties in the workplace, which can lead to performance concerns. There can be a tendency to delve in without investigation of the causal factors. There are models designed to help in such situations. The RDM-p model, for example, helps distinguish between performance and causal/influential factors (Box 3)[24].

Box 3: The RDM-p model for diagnosing problems

Relationships — relationships with others

Diagnostics — such as analytical and decision-making skills

Management — the ability to organise and manage one’s own work and that of others

Professionalism — includes attitude, honesty and integrity

The RDM-p model starts with collecting specific evidence about the trainee based on observed events — both from the trainee and others. It is important to collect as much specific evidence as possible. The evidence is then mapped to the RDM-p model, allowing performance themes to be identified. For example, a trainee who is often late may come under ‘M’ (management of one’s own time) but also ‘P’ (the professionalism domain). The trainee should be made aware of the findings and a meeting arranged to discuss the causal and influential factors using the SKIPE framework (see Box 4)[25].

Box 4: The SKIPE framework for diagnosing performance problems

Skills

Knowledge

Internal: within the individual (e.g. attitude, personality, health)

Past factors (e.g. culture, education)

External factors (e.g. work environment, home, social life)

In the example of the trainee who is often late, investigation might reveal that there has been a change to a bus timetable — this is an external factor. Considering all possible factors and asking non-judgemental questions allows the real cause of the problem to be identified and hopefully produce a solution.

Summary

A supervisor’s role is to coach, support and supervise trainees as they apply their learning within the workplace and develop new skills. There are assessment tools available to aid trainees to develop in their role by reflection upon events and feedback. It is also important for supervisors to reflect upon their own educational needs: they must ensure they have the appropriate training and qualifications and are competent to supervise a trainee in practice. The level of supervision will reduce over time as the trainee develops competence and confidence. Trainees should continue to work under supervision until they have demonstrated competence to ensure patient safety is not compromised.

- 1Styles M, Middleton H, Schafheutle E, et al. Educational supervision to support pharmacy professionals’ learning and practice of advanced roles. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022;44:781–6. doi:10.1007/s11096-022-01421-8

- 2Kilminster S, Cottrell D, Grant J, et al. AMEE Guide No. 27: Effective educational and clinical supervision. Medical Teacher. 2007;29:2–19. doi:10.1080/01421590701210907

- 3Launer J. Supervision, mentoring and coaching. In: Swanwick T, ed. Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. Oxford: : Wiley Blackwell 2013. 111–122.

- 4Whitmore J. Coaching for performance: the principles and practice of coaching and leadership. 25th ed. London: : Nicholas Brealey Publishing 2017.

- 5Jubraj B, Fleming G, Wright E, et al. Say goodbye to clinical tutors: standardising the terminology in education. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2010.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/opinion/say-goodbye-to-clinical-tutors-standardising-the-terminology-in-education (accessed Jul 2022).

- 6Armson H, Lockyer JM, Zetkulic M, et al. Identifying coaching skills to improve feedback use in postgraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2019;53:477–93. doi:10.1111/medu.13818

- 7Hart E. Seven keys to successful mentoring. San Diego, USA: : Center for Creative Leadership 2009.

- 8Narayanasamy A, Penney V. Coaching to promote professional development in nursing practice. Br J Nurs. 2014;23:568–73. doi:10.12968/bjon.2014.23.11.568

- 9Launer J. Unconscious incompetence. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2010;86:628–628. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2010.108423

- 10Burch V. The changing landscape of workplace-based assessment. Journal of Applied Testing Technology. 2019.http://jattjournal.com/index.php/atp/article/view/143675 (accessed Jul 2022).

- 11Tham TC, Burr B, Boohan M. Evaluation of feedback given to trainees in medical specialties. Clin Med. 2017;17:303–6. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.17-4-303

- 12Collins J. Foundation for Excellence: An Evaluation of the Foundation Programme. Medical Education England. 2010.http://cmec.info/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Foundation-for-Excellence-An-evaluation-of-The-Foundation-Programme-The-Collins-Report.pdf (accessed Jul 2022).

- 13Rees CE, Cleland JA, Dennis A, et al. Supervised learning events in the Foundation Programme: a UK-wide narrative interview study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005980. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005980

- 14Full programme of assessment. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2022.https://www.rpharms.com/development/credentialing/post-registration-foundation/post-registration-foundation-curriculum/programme-of-assessment/full-programme-of-assessment (accessed Jul 2022).

- 15Trainee Pharmacist Foundation Year Assessment Strategy. Health Education England. 2021.https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/HEE%20Trainee%20Pharmacist%20Foundation%20Year%20-%20Assessment%20Strategy_1.pdf (accessed Jul 2022).

- 16Cantillon P, Sargeant J. Giving feedback in clinical settings. BMJ. 2008;337:a1961–a1961. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1961

- 17Hesketh EA, Laidlaw JM. Developing the teaching instinct, 1: Feedback. Medical Teacher. 2002;24:245–8. doi:10.1080/014215902201409911

- 18McKimm J. Giving effective feedback. Br J Hosp Med. 2009;70:158–61. doi:10.12968/hmed.2009.70.3.40570

- 19Watson G. Characteristics of Good Student Feedback. YouTube. 2013.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Huju0xwNFKU (accessed Jul 2022).

- 20Chowdhury RR, Kalu G. Learning to give feedback in medical education. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2004;6:243–7. doi:10.1576/toag.6.4.243.27023

- 21Lefroy J, Watling C, Teunissen PW, et al. Guidelines: the do’s, don’ts and don’t knows of feedback for clinical education. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4:284–99. doi:10.1007/s40037-015-0231-7

- 22Pendleton D. The Consultation: an approach to learning and teaching. Oxford: : Oxford University Press 1984.

- 23Foundation training year 2021/22 — Designated supervisor development resource. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2021.https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/designated-supervisor-development-resource-2021-22_.pdf (accessed Jul 2022).

- 24Norfolk T, Siriwardena A. A unifying theory of clinical practice: Relationship, Diagnostics, Management and professionalism (RDM-p). Qual Prim Care 2009;17:37–47.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19281673

- 25Norfolk T, Siriwardena A. A comprehensive model for diagnosing the causes of individual medical performance problems: skills, knowledge, internal, past and external factors (SKIPE). Qual Prim Care 2013;21:315–23.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24119517

You might also be interested in…

RPS calls for authorisation of pharmacy technicians to supervise pharmacies to be documented

Pharmacy technicians may prepare and dispense medicines without supervision under government proposals