Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Apply the techniques of evidence-based medicine to clinical practice;

- Assess a research study’s validity, results and relevance;

- Find the best evidence that connects with the values and preferences of patients.

Finding and using research results to support professional decisions must be a systematic process, based on the principles of evidence-based medicine (EBM) and healthcare[1,2]. A previous article in this series discussed the theory of critical appraisal and how to develop skills to apply EBM to practice[3].

This article presents a hypothetical scenario in which a clinical pharmacist is required to use EBM to decipher a clinical problem. It provides a step-by-step guide, presented in the previous article, to choosing the best available option, not only based on the evidence in the literature but also considering the patient’s lifestyle and preferences.

Clinical scenario

A consultant endocrinologist seeks advice from a clinical pharmacist regarding a patient she is currently treating. The patient is at increased risk of cardiovascular events owing to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and the consultant is considering an add-on therapy of dulaglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, to improve the patient’s glycaemic control. Insulin therapy has been ruled out as the patient is fearful of self-injecting but is happy for the practice nurse at the local health centre to administer dulaglutide subcutaneous injection once a week because it is convenient and can fit around family and work commitments. The consultant wants to know whether dulaglutide added to her drug regime is as effective as insulin therapy and the risk of hypoglycaemic events.

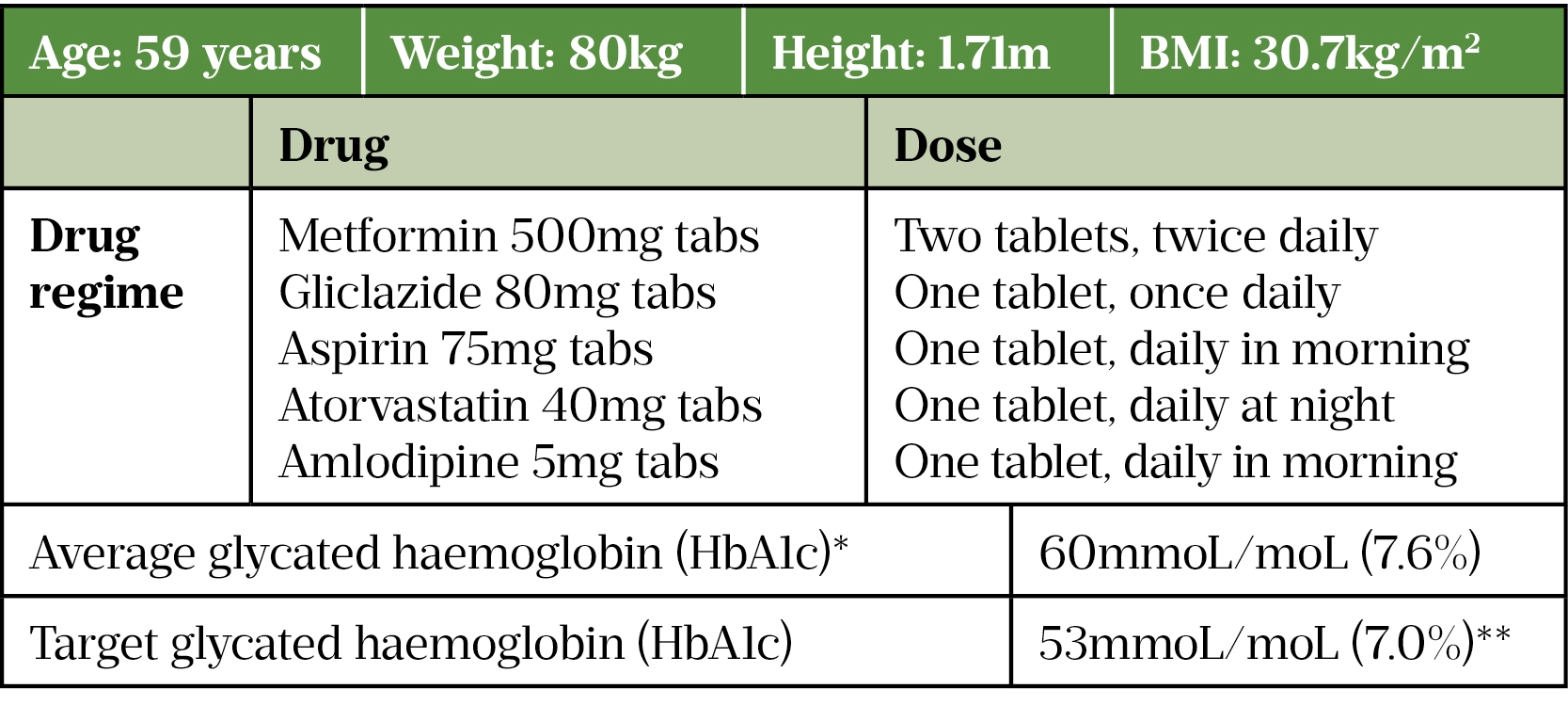

The pharmacist obtains the patient’s clinical history:

* Average blood glucose level over two to three months.

**NICE guideline recommends that for adults with T2DM who are managing HbA1c levels with lifestyle and diet alone or combined with a single drug not associated with hypoglycaemia, the target level aimed for is 48mmol/mol (6.5%). For adults on a drug associated with hypoglycaemia, an HbA1c level of 53mmol/mol should be aimed for.

The patient is moderately obese, and her clinical history indicates she is at increased risk of cardiovascular disease because she is receiving additional drug therapy to lower LDL (low density lipoproteins) cholesterol levels and blood pressure, including anti-platelet therapy (aspirin 75mg). Furthermore, she has elevated HbA1c levels of 7.6%, indicating that her current oral antihyperglycemic medication (OAM) is inadequate.

Practising evidence-based medicine

Follow the three steps below to help embed evidence-based medicine[4] into practice:

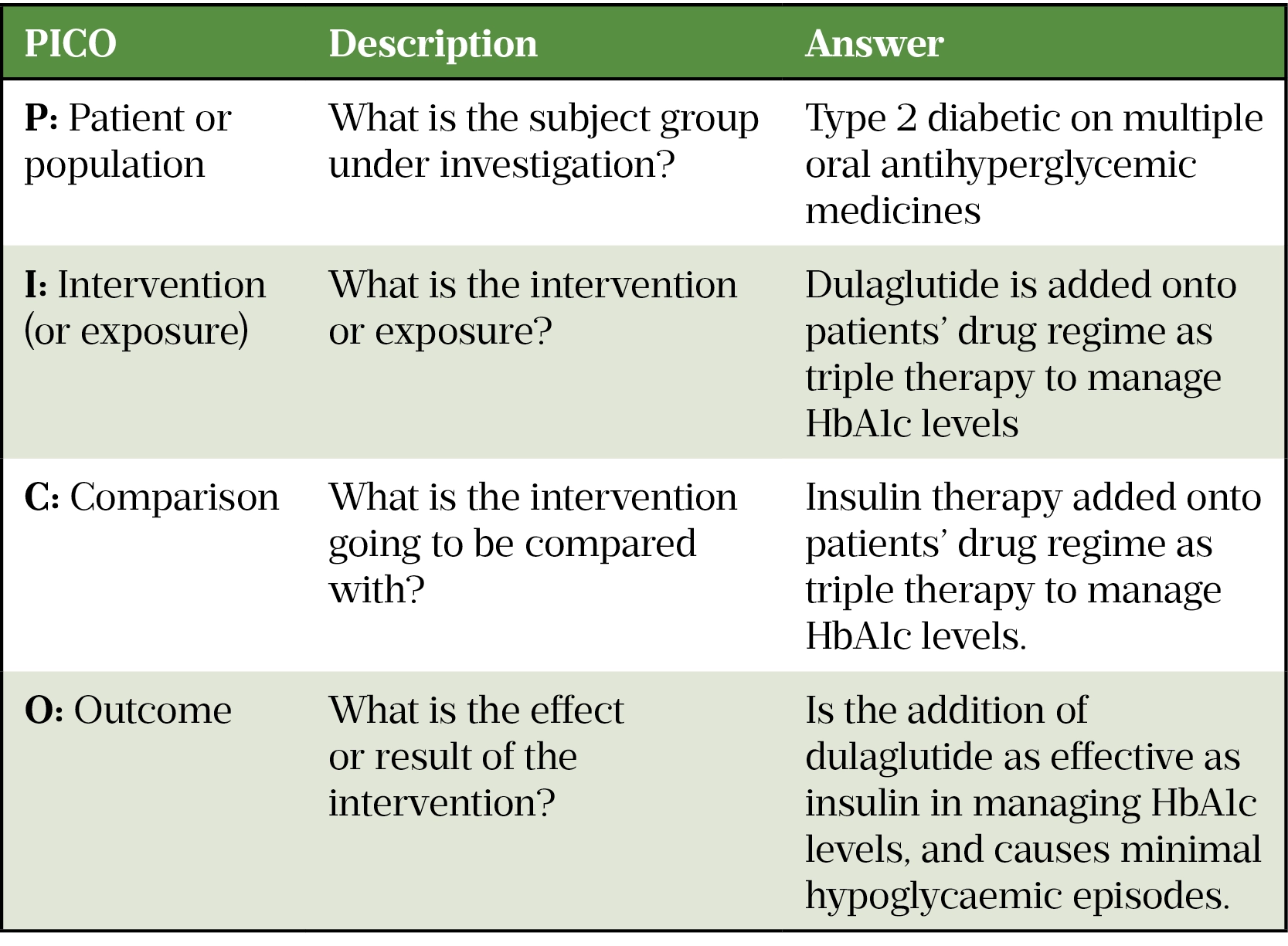

Step 1: Generate the clinical question

The first step is to convert the clinical query into an answerable question[5]. A helpful structured approach for developing appropriate clinical questions or hypotheses before conducting a literature search is by applying the population, intervention, comparator and outcome (PICO) framework and is recommended by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE; see Table 2)[6,7].

Step 2: Find the best possible evidence to answer the clinical question

By applying inclusion and exclusion criteria during a literature search, several relevant randomised clinical trials (RCTs) were identified[8,9]. In practice, several papers should be appraised to prove the effectiveness of an intervention, but only one research paper will be discussed in this article[10].

The study by Giorgino et al assessed the efficacy and safety of once-weekly dulaglutide versus insulin glargine in patients with T2DM who are already being treated with metformin and glimepiride[9]. The article can be accessed here.

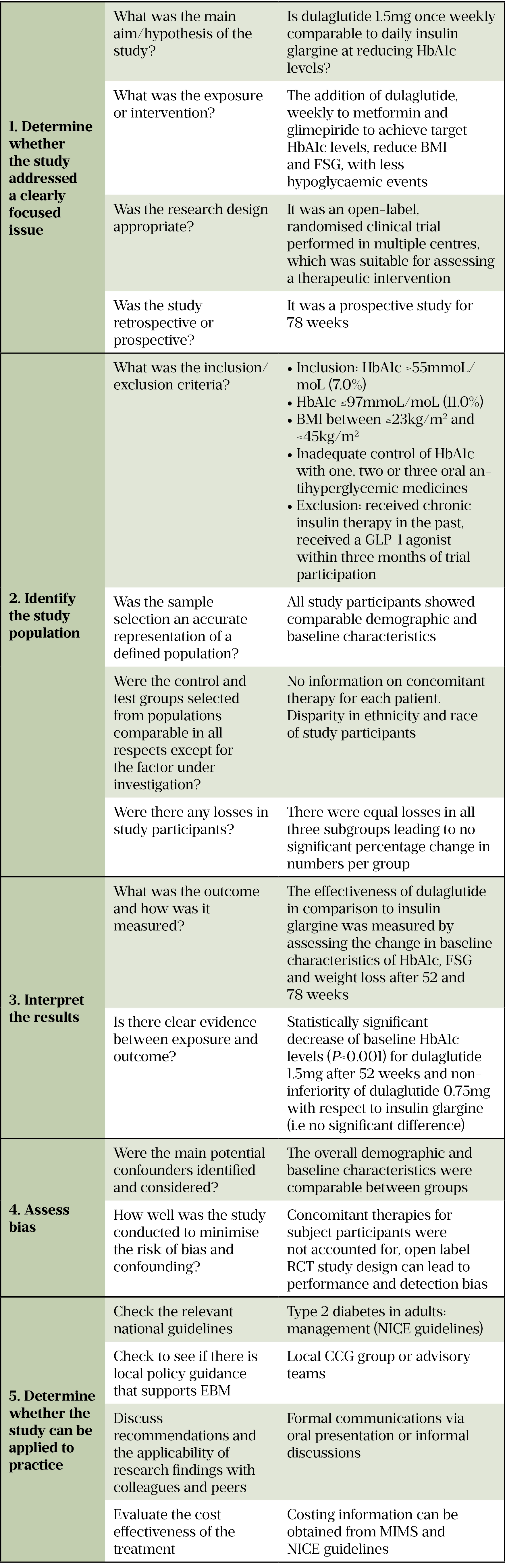

Step 3: Critically appraise the evidence

When critically appraising evidence pharmacists should use the following checklist:

1. Determine whether the study addressed a focused issue

What was the main aim/hypothesis of the study?

To determine the suitability of dulaglutide 1.5mg administered once weekly as a substitute for insulin therapy, with similar efficacy (in terms of reduction of HbA1c levels) and safety profile, as well as improved weight loss and hypoglycaemic outcomes.

Was the research design appropriate?

The research design was an open-label RCT (double-blind for the dulaglutide dose) where both the researchers and participants know which treatment is being administered[11]. A previous double-blind RCT study (dulaglutide/insulin vs placebo/insulin) established superiority for the combination therapy over the comparator, with dulaglutide proving to be efficacious and well tolerated[12]. Therefore, the current study is appropriate to gather further clinical data about dulaglutide.

Open-label trials can be conducted as follow-on studies to further determine the safety profiles of new medicines. Research ethics committees need to be convinced of the motives, as well as the quality, and its execution before supporting such studies[13]. In this case, participants, clinicians and researchers were unaware of which patient was being administered the dulaglutide dose, indicating that the purpose of this study was to determine the optimal dose of dulaglutide.

Was the study retrospective or prospective?

It was a multi-centre, prospective study.

2. Identify the study population

What were the inclusion/exclusion criteria?

Inclusion criteria:

- Adult patients;

- An HbA1c of ≥53mmol/mol (7.0%) and ≤97mmol/mol (11.0%);

- Body mass index (BMI) ≥23kg/m2 and ≤45kg/m2 and stable weight for longer than three months;

- HbA1c levels were not optimally controlled with one, two or three oral antihyperglycemic treatment (of which one had to be metformin or a sulfonylurea).

Exclusion criteria:

- Received chronic insulin therapy at any time in the past;

- Received a GLP-1 receptor agonist within three months of screening.

Was the sample an accurate representation of a defined population?

Table 1 in the original paper summarises the study group baseline and demographic characteristics. There were equal numbers of males and females in each subgroup, of similar age distribution.

The majority (72%) of the study population was white, indicating potential selection bias. A study in the New England Journal of Medicine reported the underrepresentation of minority groups in clinical trials and the lack of data to assess the effectiveness or safety of new drugs in these populations[14,15].

Were the control and test groups selected from populations comparable in all respects except for the factor under investigation?

Baseline characteristics measured for study participants at the point of screening were similar across all three subgroups. All patients were stabilised on the same two oral antihyperglycemic drugs.

Were there any losses of study participants?

In total, 11% of participants (87) dropped out of the study. It is generally accepted that an attrition rate of up to 20% in RCTs is acceptable and will not introduce significant bias to the outcome[16,17]. The percentage of participants lost was the same across all three groups within the study, indicating no significant disparity in group numbers. Furthermore, participant losses were explicitly accounted for in the study design[9] (see Figure 1 in original paper).

3. Interpret the results

What was the outcome and how was it measured?

The primary outcome was the decrease in baseline HbA1c compared with the change in baseline achieved with insulin glargine. Other outcomes were the number of patients achieving target HbA1c levels, fasting serum glucose (FSG), and weight loss. Hypoglycaemic events were assessed to determine the safety profile of dulaglutide.

Changes from baseline in HbA1c were analysed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), in which factors for treatment, country and baseline values were used as covariates. This mathematical programme is recommended for RCTs when a quantitative outcome of before-treatment and after-treatment differences is determined[18].

Is there clear evidence of a link between exposure and outcome?

There was clear evidence of statistically significant differences between the dulaglutide 1.5mg group and the insulin glargine group.

Dulaglutide 1.5mg was found to have superior efficacy to insulin glargine (P<0.001) and dulaglutide 0.75mg was found to have similar efficacy to insulin glargine (P<0.001). Throughout the trial, patients in the dulaglutide treatment group exhibited a loss in body weight, while those in the insulin glargine group gained weight (P<0.001). There was a greater reduction in FSG for patients in the insulin glargine group (P<0.001).

4. Assess the bias

Were the main potential confounders identified and considered?

A confounder is defined as “a variable, other than the one studied, that can distort the outcome of interest”[19]. In any research, some confounders should be considered in the planning phase of a trial and must be accounted for[20].

In this study, randomisation was stratified by country and baseline HbA1c. Stratified random sampling uses random selection within each group to ensure that no bias, deliberate or accidental, interferes with the representative nature of the patient sample[21].

The overall demographic and baseline characteristics in this study were comparable between groups. Therefore, the main confounders that could influence the outcome of the study (age, weight, BMI, FSG and HbA1c) were accounted for[22].

How well was the study conducted, to minimise the risk of bias and confounding?

Two confounding factors were not accounted for in this clinical trial.

- Concomitant therapy, such as long-term glucocorticoid therapy, can induce hyperglycaemia and therefore influence study outcomes[23]. There was no information regarding additional therapy being taken by the study participants;

- The difference in administration of oral dulaglutide versus subcutaneous insulin does not permit blinding and was not concealed from patients and clinicians, except for the different dulaglutide doses (0.75mg or 1.5mg)[24]. Therefore, the chances of performance bias and detection bias is increased.

5. Determine whether the results can be applied to practice

Check the relevant national guidelines

According to NICE guidance, if triple therapy with metformin and two other OAMs is not effective, not tolerated or contraindicated then combination therapy with metformin, a sulfonylurea and a GLP-1 agonist should be considered[25]. For those patients who have a BMI <35kg/m2 and are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and would benefit from weight loss, the addition of a GLP-1 agonist, such as dulaglutide, is also recommended.

Check for local clinical policies that are supported by EBM

Review any relevant local guidelines published by clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) or local advisory teams. All the published guidelines follow a similar format, providing a detailed account of advice, recommendations and treatment algorithms which are supported by EBM, developed to support the implementation of NICE guidelines[26,27].

Discuss the applicability of research findings with peers

Whether it is an informal discussion with a colleague or a more formal oral presentation, it is necessary to share your findings with people of similar competencies who can review and evaluate your work. The process functions like the peer-review process in scientific publishing[28].

Evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the treatment

Making an informed choice of treatment for a patient is not as simple as selecting the cheapest option[29]. All potential treatments should be evaluated for cost but also considered in combination with the patient’s values and lifestyle, as well as providing efficacy and long-term safety. Therefore, although dulaglutide is the more expensive option, its benefits outweigh the cost, in terms of beneficial health outcomes (statistically significant reduction in hypoglycaemic events and reduction in BMI), and patient choice. There is strong evidence to show that involving patients in decisions about their treatment not only improves decision making, but also prevents the overuse of treatments that informed patients do not value[30].

Costing information for dulaglutide and insulin glargine can be obtained from various sources, including NICE guidelinesand the Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS), which is a pharmaceutical prescribing reference guide[25][31,32].

Decision

After evaluating the evidence, the pharmacist can now provide the consultant with advice and guidance.

Advantages of dulaglutide treatment

- Dulaglutide 1.5mg, administered once weekly, is more effective at lowering HbA1c levels than insulin glargine. Therefore, the patient could benefit from the addition of dulaglutide to their treatment regime.

- As the patient does not like self-injecting, dulaglutide would be more suitable for her, since it is only administered once weekly, as opposed to insulin glargine that is injected daily.

- There were significantly fewer hypoglycaemic events experienced by study participants on dulaglutide therapy.

- Dulaglutide therapy causes statistically significant weight loss in comparison to insulin glargine that tends to cause weight gain. NICE guidelines recommend the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists if weight loss is beneficial to those patients with obesity-related comorbidities, therefore the patient’s clinical history indicates suitability that fits this criteria.

Disadvantages of dulaglutide treatment

- The cost of dulaglutide treatment for one year is greater than for insulin glargine[25,31,32].

- There is considerably more clinical and safety data on insulin glargine, as it has been in use for longer (received approval in June 2000)[33].

It is also feasible to discuss other treatment options with the consultant, as recommended by NICE guidelines[25]. The consultant might consider triple therapy with add-on OAMs such as dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor or pioglitazone[34,35]. This might be more agreeable to the patient, as she could avoid injections altogether. However, adverse effects, particularly an increased risk of hypoglycaemia, would have to be carefully considered if that option were selected.

Conclusion

This example demonstrates how to use EBM in clinical practice to make a logical and balanced decision. By accounting for the patient’s choices in treatment decisions, medication adherence is far more likely.

It is important to emphasise that it is not feasible to base clinical recommendations on a single study. In the scenario discussed above, it would be advisable to critically appraise more research, including studies that show dulaglutide in a less favourable light. Consequently, a more balanced argument could be presented to the consultant, so she can inform the patient of the various advantages and disadvantages of selecting dulaglutide over insulin as management of T2DM.

- 1Catchpole K, Bowie P, Fouquet S, et al. Frontiers in human factors: embedding specialists in multi-disciplinary efforts to improve healthcare. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2020;33:13–8. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzaa108

- 2Kelly MP, Heath I, Howick J, et al. The importance of values in evidence-based medicine. BMC Med Ethics 2015;16. doi:10.1186/s12910-015-0063-3

- 3Critical appraisal: how to evaluate research for use in clinical practice. Pharmaceutical Journal Published Online First: 2021. doi:10.1211/pj.2021.1.85492

- 4Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996;312:71–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

- 5Richardson W, Wilson M, Nishikawa J, et al. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. American College of Physicians Journal Club. 1995.https://asset-pdf.scinapse.io/prod/1572319397/1572319397.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 6Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014.https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/chapter/developing-review-questions-and-planning-the-evidence-review (accessed Nov 2021).

- 7Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, et al. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2007;7. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-7-16

- 8Tuttle KR, Lakshmanan MC, Rayner B, et al. Dulaglutide versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease (AWARD-7): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2018;6:605–17. doi:10.1016/s2213-8587(18)30104-9

- 9Giorgino F, Benroubi M, Sun J-H, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Once-Weekly Dulaglutide Versus Insulin Glargine in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes on Metformin and Glimepiride (AWARD-2). Dia Care 2015;38:2241–9. doi:10.2337/dc14-1625

- 10Rychetnik L. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2002;56:119–27. doi:10.1136/jech.56.2.119

- 11Understanding clinical trial terminology: what is an open-label clinical trial? Concert Pharmaceuticals. 2019.https://www.concertpharma.com/understanding-clinical-trial-terminology-what-is-an-open-label-clinical-trial/ (accessed Nov 2021).

- 12Pozzilli P, Norwood P, Jódar E, et al. Placebo-controlled, randomized trial of the addition of once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist dulaglutide to titrated daily insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD-9). Diabetes Obes Metab 2017;19:1024–31. doi:10.1111/dom.12937

- 13Day RO, Williams KM. Open-Label Extension Studies. Drug Safety 2007;30:93–105. doi:10.2165/00002018-200730020-00001

- 14King TE Jr. Racial Disparities in Clinical Trials. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1400–2. doi:10.1056/nejm200205023461812

- 15Clark LT, Watkins L, Piña IL, et al. Increasing Diversity in Clinical Trials: Overcoming Critical Barriers. Current Problems in Cardiology 2019;44:148–72. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.11.002

- 16Dumville JC, Torgerson DJ, Hewitt CE. Reporting attrition in randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2006;332:969–71. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7547.969

- 17Bell ML, Kenward MG, Fairclough DL, et al. Differential dropout and bias in randomised controlled trials: when it matters and when it may not. BMJ 2013;346:e8668–e8668. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8668

- 18Van Breukelen GJP. ANCOVA versus change from baseline had more power in randomized studies and more bias in nonrandomized studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2006;59:920–5. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.02.007

- 19Attia A. Bias in RCTs: confounders, selection bias and allocation concealment. Middle East Fertil Soc J 2005;10:258–261.http://www.bioline.org.br/pdf?mf05044

- 20Boussageon R, Supper I, Erpeldinger S, et al. Are concomitant treatments confounding factors in randomized controlled trials on intensive blood-glucose control in type 2 diabetes? a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-107

- 21Patient stratification in clinical trials. Omixon (news). 2014.https://www.omixon.com/patient-stratification-in-clinical-trials/

- 22Cantrell RA, Alatorre CI, Davis EJ, et al. A review of treatment response in type 2 diabetes: assessing the role of patient heterogeneity. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2010;12:845–57. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01248.x

- 23Nowak KM, Rdzanek-Pikus M, Romanowska-Próchnicka K, et al. High prevalence of steroid-induced glucose intolerance with normal fasting glycaemia during low-dose glucocorticoid therapy: an oral glucose tolerance test screening study. Rheumatology 2020;60:2842–51. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keaa724

- 24Boutron I, Tubach F, Giraudeau B, et al. Blinding was judged more difficult to achieve and maintain in nonpharmacologic than pharmacologic trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2004;57:543–50. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.12.010

- 25Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. NICE guidelines [NG28]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 26Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus – Anti-Hyperglycaemic Treatment Pathway. Mid and South Essex Health and Care Partnership. 2021.https://midessexccg.nhs.uk/medicines-optimisation/clinical-pathways-and-medication-guidelines/chapter-6-endocrine-system-2/4248-adult-t2dm-treatment-guidelines/file (accessed Nov 2021).

- 27Waltham Forest and East London Medicines Optimisation and Commissioning Committee. Blood glucose management in type 2 diabetes in adults. Waltham Forest CCG. 2017.https://www.walthamforestccg.nhs.uk/downloads/ourwork/Medicines-optimsation/Medicines-guidelines/Endocrine/WEL-Type2-diabetes-guidance.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 28Weatherspoon D, Felman A. What to know about peer review. Medical News Today. 2019.https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/281528 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 29Zolkefli Y. Evaluating the Concept of Choice in Healthcare. MJMS 2017;24:92–6. doi:10.21315/mjms2017.24.6.11

- 30O’Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, et al. Toward The ‘Tipping Point’: Decision Aids And Informed Patient Choice. Health Affairs 2007;26:716–25. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.716

- 31Type 2 diabetes: dulaglutide. Evidence summary [ESNM59]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015.https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/esnm59/chapter/Key-points-from-the-evidence (accessed Nov 2021).

- 32Monthly Index of Medical Specialities. MIMS. https://www.mims.co.uk (accessed Nov 2021).

- 33Lantus – insulin glargine. EPAR summary for the public. European Medicines Agency. 2012.https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/overview/lantus-epar-summary-public_en.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 34Gallwitz B. Clinical Use of DPP-4 Inhibitors. Front Endocrinol 2019;10. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00389

- 35Alam F, Islam MdA, Mohamed M, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pioglitazone Monotherapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Sci Rep 2019;9. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41854-2