Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Differentiate between haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, including their main processes and benefits;

- Identify and mitigate complications specific to each dialysis modality;

- Understand the physiological changes that occur in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and how this affects medicines dosing and monitoring;

- Know the role of the pharmacist in managing patients with ESRD.

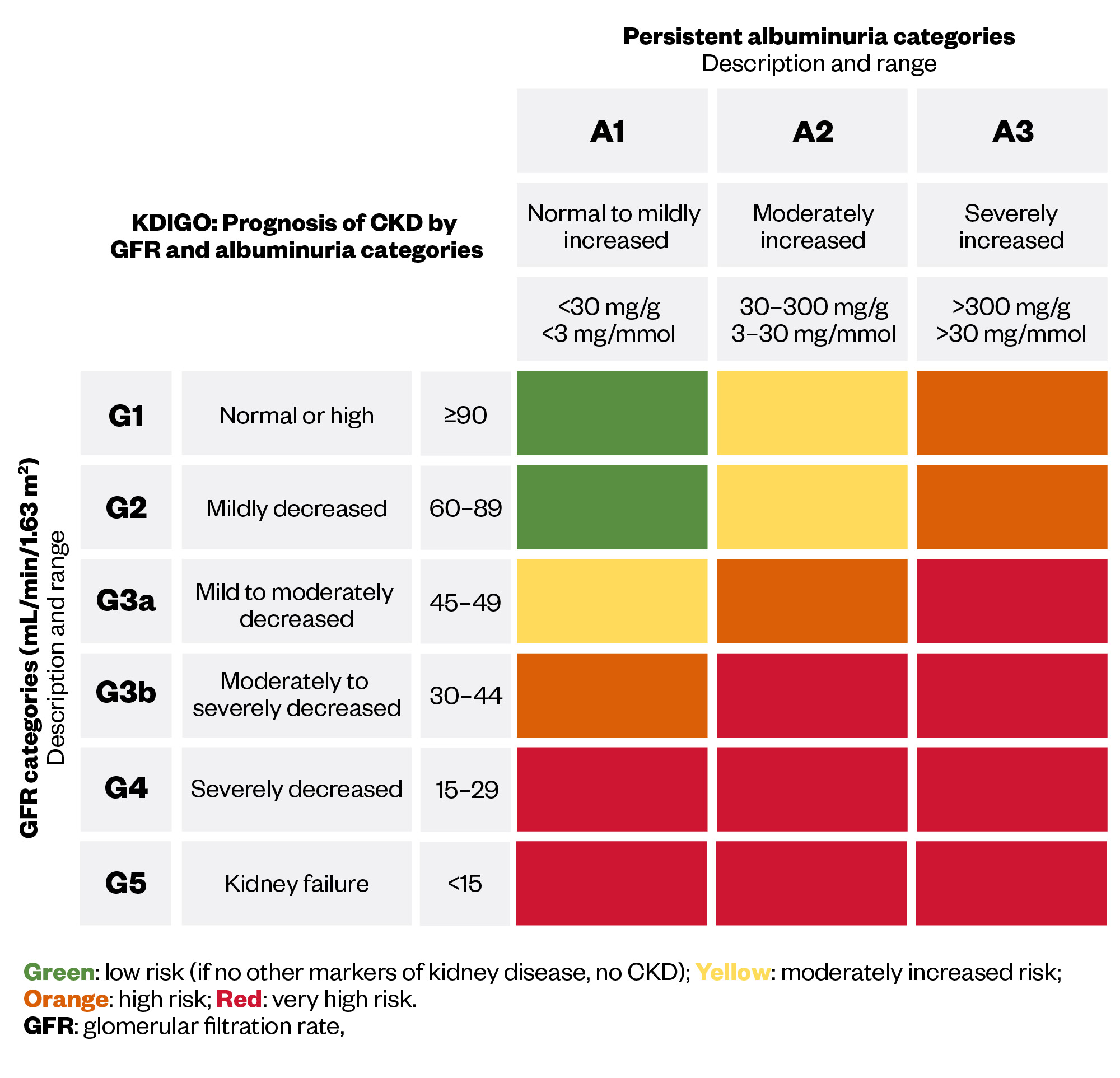

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) represents a significant global health challenge, affecting an estimated 10% of the population worldwide1. This trend is mirrored in the UK with more than 7 million people experiencing the condition2. CKD profoundly reduces quality of life, leads to premature death and is forecast to be the fifth highest cause of years of life lost by 20403,4. CKD is diagnosed when abnormalities in the kidney structure or function are present for more than three months, leading to gradual loss of kidney function over time. CKD is a progressive condition, which is classified as stages 1–5 (see Figure 1) using the calculated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in conjunction with the urine albumin–creatinine ratio5.

The risk of all-cause mortality increases as CKD progresses, with a large proportion of deaths in those with CKD being attributed to cardiovascular events, such as stroke and myocardial infarction7. Those who reach stage 5 CKD are deemed to be in kidney failure or end-stage renal disease (ESRD). At this point, the kidneys can no longer perform their excretory (e.g. removing urea or water), endocrine (e.g. erythropoiesis) and regulatory functions (e.g. maintaining pH) and maintain a physiological fluid and electrolyte balance8. Patients who progress to ESRD experience an array of symptoms, including fatigue, bone pain, itching, breathlessness and reduced urine output6. ESRD is ultimately fatal without intervention with renal replacement therapy (RRT), although some patients may opt for supportive care, such as symptom management and psychological support9. The management of CKD before ESRD is beyond the scope of this article, please consult the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) ‘Chronic kidney disease: assessment and management’ guideline for more information10.

Pharmacists are involved in the management of patients on RRT by ensuring the safe and effective use of medicines, including dose adjustments, patient education and the facilitation of medicines supply. This article will provide an overview of the different types of RRT, their associated complications and considerations for medicines use.

Initiating renal replacement therapy

RRT replaces the non-endocrine kidney functions in patients with ESRD and allows for the removal of uraemic toxins. The therapy is commenced when those with ESRD have one or more of the following intolerable symptoms: uncontrollable acidosis, electrolyte imbalances, such as hyperkalaemia, uraemic symptoms or fluid overload refractory to diuretic therapy11. Assessment and preparation for RRT should ideally begin at least one year before it is likely to be needed to allow for adequate discussion and consideration of options11.

However, in practice, patients with ESRD often present late to renal services requiring dialysis with minimal prior nephrologist input — colloquially known as ‘crash-landers’. In 2022, 18.5% of individuals who started RRT were first seen by kidney services within 90 days of commencing treatment. Initiating dialysis in this manner is associated with higher mortality rates and lower quality of life12–14.

According to the ‘UK Renal Registry 26th annual report’14, in 2022, around 71,000 people in the UK relied on RRT to manage their ESRD — this included haemodialysis (HD), peritoneal dialysis (PD) and renal transplantation. Renal transplantation is the most commonly used form of RRT (56.2%) and is associated with the best outcomes; however, waiting lists for transplantation average 2.5–3.0 years. In-centre haemodialysis is the second most common RRT (36.4%), followed by peritoneal dialysis (5.4%) and home haemodialysis (2.1%)14. Mortality rates for patients initiating dialysis remain high, with unadjusted five-year survival rates lower than those for men with prostate cancer and women with breast cancer15.

Both clinical and social factors play a role in the selection of RRT modality. The ‘Getting it right first time (GIRFT)’ report, published in March 202116, recommends that 20% of patients on RRT should utilise a home-based modality, such as PD or home haemodialysis (HHD). The choice between PD and HD should be the patient’s prerogative, which is independent of clinician bias or resource constraints. An individualised, person-centred approach with empowered patients choosing their dialysis modality has a lower mortality risk and increased rates of transplantation17.

The ability to perform RRT in the home environment, without the need to travel to a dialysis unit, gives patients more freedom and autonomy. This benefits those who live in remote areas and who would otherwise have to travel significant distances to receive in-centre HD18.

Box 1: When learning about RRT, it is important to be aware of the following definitions

- Extracorporeal circuit: Blood circuit that occurs outside the body;

- Solutes: A substance that is dissolved in a liquid or solvent (i.e. sodium) and urea are solutes in blood;

- Solvent: A substance, usually a liquid, which dissolves a solute to form a solution;

- Diffusion: Passive movement of molecules from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration until an equilibrium is achieved;

- Diffusion gradient: The difference in concentration of a substance between two areas. Steeper gradient leads to a faster rate of diffusion;

- Diffusion coefficient: The measure of how a solute moves through a medium, owing to diffusion;

- Convection: The movement of solutes, owing to pressure gradients rather than differences in concentration;

- Hydrostatic pressure: The pressure exerted by a fluid through gravitational force;

- Ultrafiltration: Process that removes excess fluid from the blood during dialysis19.

Haemodialysis

HD is a form of RRT involving extracorporeal filtration of blood using a dialysis machine. HD can be provided for inpatients, outpatients and for some patients at home. The most common setting for haemodialysis in the UK is in nurse-led, outpatient dialysis units where patients attend treatments three times per week, but frequency can vary depending on clinical need20. In 2022, there were over 25,000 people using in-centre haemodialysis in the UK, which is the second most common form of RRT after transplantation14.

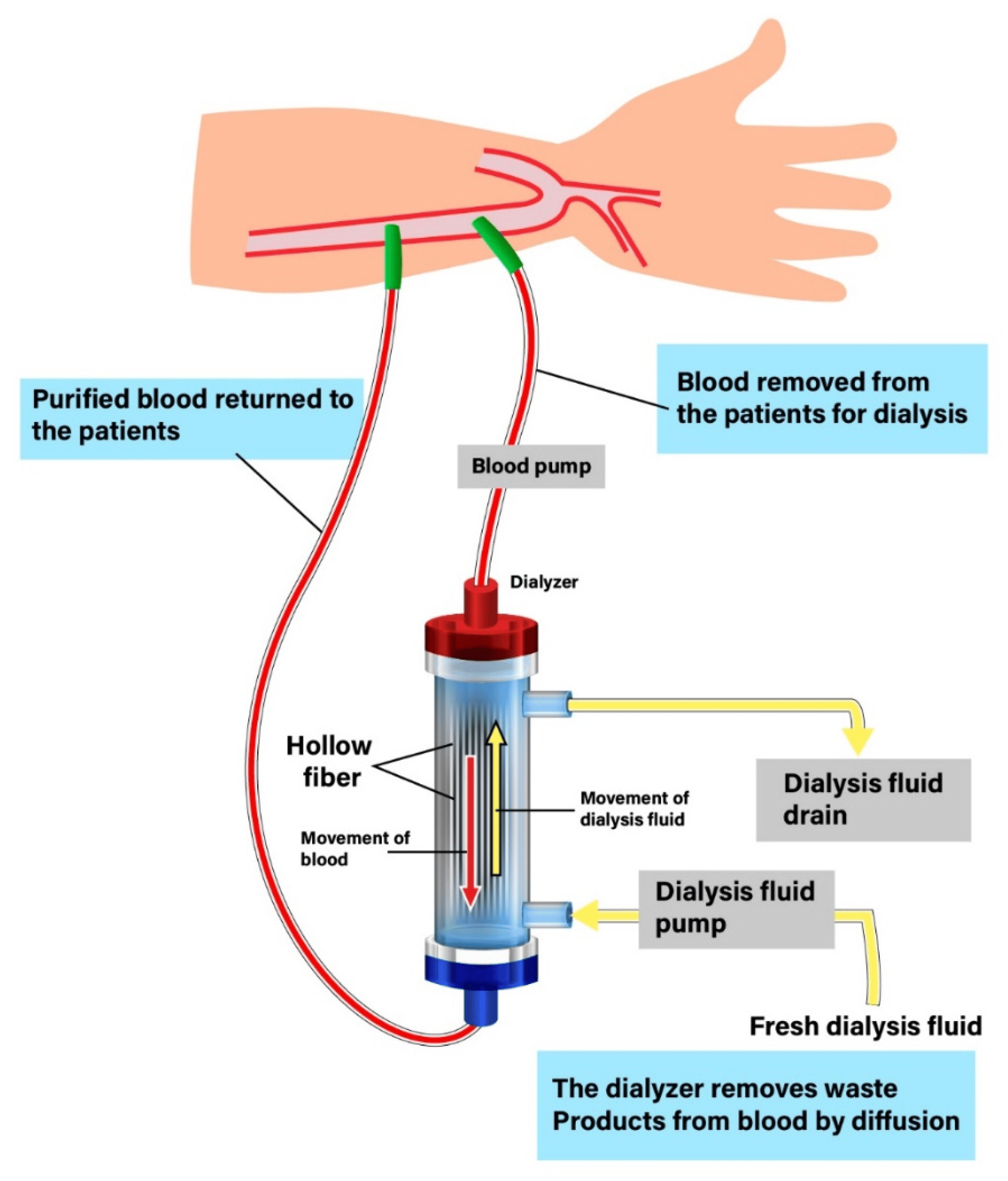

During HD, blood is removed from the patient and passed through a dialyser, followed by venous return of filtered blood to the patient (see Figure 2). The dialyser contains hollow, tube-like fibres made from cellulose or synthetic polymers21. The dialysers’ hollow and porous shape creates a large surface area for blood and dialysis fluid to pass through, allowing for removal of solutes through diffusion and convection21. Dialysers are classified as low or high-flux, which correlate to pore size, where high-flux dialysers have a larger pore size. This difference in pore size allows for an increased clearance of uraemic toxins and medicines in high-flux HD22.

Dialysis fluid, or dialysate, is a mixture of electrolytes and purified water that flows in the opposite direction to blood to maximise diffusion gradients23. The selection of dialysis fluid is bespoke, accounting for the patient’s biochemistry22. For example, a low-potassium dialysate (1.0-3.0mmol/L) may be used for patients at risk of hyperkalaemia, especially those prescribed a maximal dose of a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor or with a high-potassium diet. This creates a greater concentration gradient, facilitating correction of hyperkalaemia.

Anticoagulation is often administered during HD and is used to prevent clotting of the extracorporeal circuit. Unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparins are commonly used. However, the decision to use anticoagulation is influenced by multiple factors, such as systemic anticoagulation and bleeding risk, and must be tailored to each patient22.

The rate of diffusion is dependent on the concentration difference, diffusion coefficient of the membrane and the flow rate of both blood and dialysate. The movement of solutes, along with their solvent through convection, owes to an increase in hydrostatic pressure where the rate of convection is dependent on molecular size. This process is most important for molecules too large for diffusion, but still smaller than the membrane pores25,26. These middle-sized molecules, such as beta-2-microglobulin and tumour necrosis factor-alpha, are plasma proteins and are postulated to contribute to uraemia and increase cardiovascular disease risk27. Larger molecules, such as albumin (60,000 Da) and monoclonal antibodies (approximately 150,000 Da), are too large to pass through the membrane pores and, hence, will not be removed by HD23.

Ultrafiltration on HD refers to the removal of plasma water from blood through a pressure gradient across the dialysis membrane. This mechanism of HD is responsible for achieving euvolemia (i.e. optimal fluid balance) in patients with ESRD26. To prevent excess fluid weight gain, a large majority of patients are dialysed on alternate days with a two-day dialysis-free window per week. Although this schedule is the most common, some patients may require dialysis more or less frequently. Patients are typically assigned a target dry weight, representing optimal weight when free of excess fluid23.

Vascular access

Patients undergoing HD need permanent vascular access. There are three main types of dialysis access: arteriovenous fistulas, grafts and tunnelled central venous catheters28. There are many factors that must be considered when selecting vascular access. The risk of infection and bloodstream infections is higher in patients with catheters when compared with grafts and fistulas28. The UK Kidney Association’s (UKKA) ‘Clinical practice guidelines vascular access for haemodialysis’28 involved a systematic literature search, comparing mortality, access complications and patient experience.

The report concludes that fistulas are preferred, owing to fewer associated complications; however, patient choice, vascular anatomy and clinical urgency should be considered28. The NHS provides financial incentives and renumerates institutions according to type of vascular access used. However, trusts are paid 20% less for catheter patients when compared with fistula or grafts, owing to differing rates of complications28. Table 1 provides an overview of the different dialysis access types.

Table 1: Common access types for haemodialysis29,30

Complications

Patients established on HD are susceptible to complications related to the pathophysiology of their underlying disease, alongside the treatment itself. Complications associated with HD include, but are not limited to, dialyser reactions, cramps, infection and difficulties obtaining vascular access31. Uncommonly, a phenomenon known as dialysis disequilibrium syndrome can occur when there is rapid solute removal from the extracellular space. This is more commonly observed in patients for whom there is an urgent need for dialysis owing to metabolic acidosis or uraemia. Patients may experience nausea, headaches, blurred vision and, in severe cases, convulsions that stem from cerebral oedema. The risk can be minimised by dialysing acutely unwell patients for shorter periods of time, to allow for less rapid extracellular solute shifts32,33.

Intradialytic hypotension

One of the most common complications of HD is intradialytic hypotension (IDH), which has a prevalence of around 11%34,35. The European best practice guidelines define IDH as a fall of ≥30mmHg of systolic blood pressure during dialysis34. The pathophysiology of IDH is multifactorial. It is caused by a combination of cardiac (e.g. decreased cardiac output) and autonomic responses (e.g. decreased vasoconstriction) to hypovolaemia (i.e. loss of volume) during ultrafiltration.

IDH has been linked with increased mortality in dialysis patients; therefore, various strategies have been adopted by clinicians to minimise this risk36,37. These strategies include dialysing patients lying flat, as opposed to sitting upright, minimising food intake during dialysis, decreasing core body temperature and administrating centrally acting sympathomimetics, such as midodrine; however, evidence for this is limited36,37. The biggest challenge for clinicians remains minimising fluid weight gain between dialysis sessions, which highlights the importance of accurate fluid assessments38.

Owing to the multi-factorial nature of the condition, there is a lack of research on the impact of antihypertensives on IDH. For patients with IDH, withholding antihypertensives on the morning of administering HD is a logical approach35. There is emerging evidence that haemodiafiltration (HDF) should be used in patients with minimal native function, as well as patients with IDH. HDF refers to the combination of diffusion and convection being applied simultaneously. A differentiating factor between low, high-flux HD and HDF is the large amount of fluid replacement given on HDF to allow for greater net ultrafiltration22.

Peritoneal dialysis

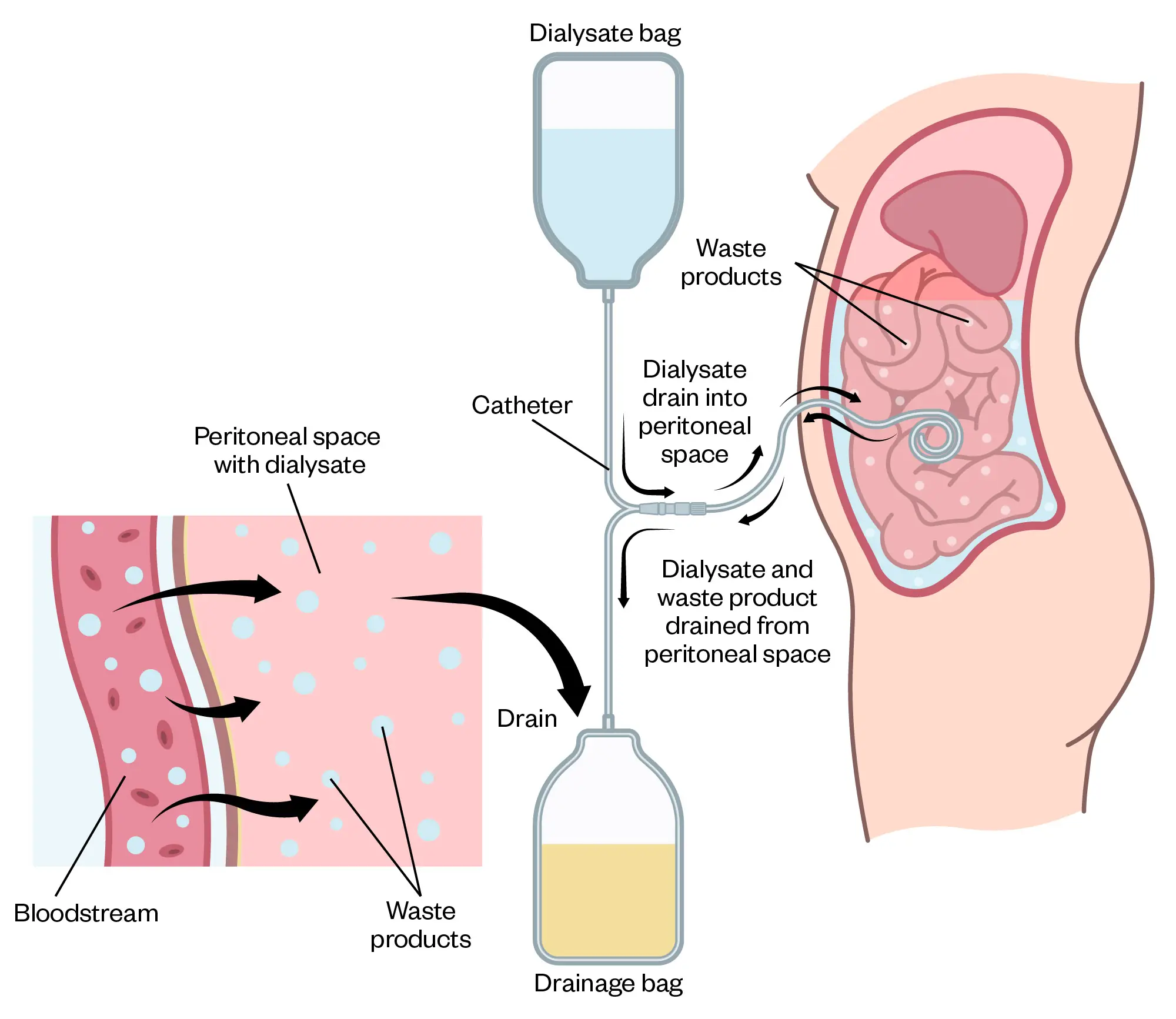

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is another dialysis modality available for patients requiring RRT. In 2022, there were around 3,800 in the UK using PD14. In PD, a dialysis solution, known as PD fluid, is introduced into the peritoneal cavity, where it comes into contact with the peritoneum, which is membrane that lines the abdominal cavity (see Figure 3). The peritoneum is highly vascular, with a large surface area, and acts as a semi-permeable membrane for dialysis39. The PD fluid sits in the peritoneal cavity for a defined period, which is known as a dwell. Uraemic toxins and solutes, such as potassium, diffuse from the blood into the PD fluid in a mechanism similar to HD.

The rate of diffusion diminishes with time and will eventually cease when equilibrium occurs between the plasma and the PD fluid. In contrast to HD, where ultrafiltration relies on hydrostatic pressure, PD utilises osmotic pressure created by the hypertonic nature of PD fluid40. The glucose content of the PD fluid is responsible for creating the osmotic gradient, where greater glucose concentrations result in increased ultrafiltration. Solutes are also removed by convection when water movement across the membrane drags solutes alongside it39,41.

A PD catheter is required to provide access to the peritoneal cavity. The catheter is made from silicone rubber, containing one or two cuffs, and tunnels through the abdominal wall. The catheter can be placed percutaneously or laparoscopically under local or general anaesthesia, respectively. Most PD centres offer both options to aid patient choice and ensure timely insertions. PD catheters ideally require a break-in period of two weeks before starting PD to minimise mechanical complications. However, urgent (<72 hours) or early start (3–14 days) strategies can be used42,43. The break-in window allows dialysis nurses and technicians to train patients how to carry out PD safely, with emphasis on PD catheter exit-site care and the development of an aseptic catheter connection technique44.

Shutterstock.com

There are two types of PD: continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) and automated peritoneal dialysis (APD)45. CAPD requires the patient to manually infuse the PD fluid into the peritoneal cavity using gravity and then disconnect the system. The PD fluid will then dwell for four to six hours to allow dialysis and ultrafiltration to occur. The system is then reconnected, and the used dialysate is drained out into an empty bag, discarded and replaced by fresh PD fluid45. This process of instillation and drainage is known as an exchange. CAPD can require between one and four exchanges per day, which is carried out by the patient themselves or with assistance from a carer or relative. Ambulant patients can go about their day-to-day activities during the dwell period45.

In APD, a machine is used to carry out multiple exchanges automatically, usually overnight46. Assisted PD is also available in some units, this involves a trained nurse or technician assisting the patient in their home to perform all or part of their dialysis. This makes PD more accessible for those who prefer home therapy but may be frail or of older age47.

PD fluid is available in a range of sizes and in different glucose concentrations. This allows for bespoke prescriptions for each patient for adequate fluid and solute removal. Although fluid with higher glucose concentrations provide more effective ultrafiltration, they are usually avoided, as excessive glucose absorption through the peritoneum leads to detrimental functional changes and disruptions to glycaemic control46,48. Icodextrin, a starch-based polymer is used as an alternative to glucose and can dwell effectively for 8–16 hours. Exchanges with icodextrin are only suitable for once daily use owing to accumulation of its metabolites and are usually reserved for the final exchange of the day49.

There are many patient-reported benefits of PD over in-centre HD, including the increased flexibility around dialysis schedules. The flexibility of PD can favour those who wish to maintain or apply for employment50. Patients with vascular disease may prefer PD, as there is no requirement for permanent vascular access.

Some limitations to PD include the space taken up by PD supplies and can lead to medicalisation of the home environment50. PD fluid is delivered directly to the patient’s home from suppliers in large boxes and patients need adequate space to accommodate this. The process of PD can leave patients feeling full and bloated, as the fluid sits in the peritoneum. Not everyone is suitable for PD. While there are no absolute medical contraindications, those who have had previous abdominal surgery or with inflammatory bowel disease would need special consideration44. It remains difficult to ascertain if patients have better outcomes on PD when compared with HD, owing to variations in patient characteristics and comorbidities18.

Complications

Complications related to PD are not uncommon and are a significant cause of mortality and morbidity. The complications are broadly divided into infective and non-infective in nature41.

The most common infective complication of PD is bacterial peritonitis, which is a serious infection associated with increased hospital admission and alterations to the peritoneal membrane and death. Peritonitis presents as abdominal pain with cloudy dialysis effluent. When sent for analysis, the dialysis effluent has a high white cell count and a positive culture51. Gram-positive bacteria are the most implicated pathogen in PD peritonitis but gram-negative, fungal and culture negative peritonitis are also observed.

Empirical antimicrobial therapy should be commenced promptly — preferably administered intra-peritoneally by adding the antimicrobial agent to the PD fluid. Empiric treatment should cover both gram-negative and gram-positive pathogens before being rationalised accordingly after the culture results. In 2022, the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) published guidelines on the management of PD peritonitis, including stability data of various antimicrobial agents in PD fluid51.

Other infective complications, such as exit-site infections and tunnel infections, can precipitate peritonitis52. Preventing infectious complications is an essential strategy used to improve outcomes and focuses on assessment of PD exchange technique43, exit-site care and the appropriate use of prophylactic antimicrobials47,52. Topical application of antibacterials to the exit site, such as mupirocin nasal ointment, is recommended daily after cleaning. Caution should be exercised to minimise contact between topical antimicrobials and the PD catheter, as excipients in mupirocin ointment and gentamicin cream itself may lead to cracks and damage52.

Non-infective complications of PD include catheter-related mechanical issues and metabolic complications. Mechanical issues, such as fluid leaks or flow dysfunction, are often caused by constipation, when the distended bowel presses on the PD catheter18. It is, therefore, important for patients on PD to have regular bowel motions with the assistance of stimulant laxatives or stool softeners, where necessary. Metabolic complications are attributed to the glucose content in the PD dialysate that lead to weight gain and glycaemic dysregulation41.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations

Patients with ESRD have high symptom burdens and multiple comorbidities — each requiring complex medicines regimens53. The prevalence of polypharmacy in this population, combined with altered drug pharmacokinetics and reduced renal function, predisposes patients to medicines-related issues54. Pharmacists, therefore, play a pivotal role within the renal multidisciplinary team through detecting, resolving and preventing drug-related problems. Their knowledge of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics is utilised to tailor and optimise challenging medicines regimens to avoid toxicity and enhance efficacy55,56.

The progression of ESRD results in changes to drug response and susceptibility to adverse effects through altered pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters (see Table 2 and 3).

Table 2: Pharmacodynamic changes that occur in ESRD54–59

Table 3: Pharmacokinetic changes that occur in ESRD60–64

Medicines management in RRT

For patients requiring HD, pharmacists must consider additional factors to optimise therapy. For example, the potential for drug removal on dialysis will determine when a drug should be prescribed in the context of dialysis, if a top-up dose is required or if the dose needs to be altered. The removal of a drug on dialysis is dependent on its molecular weight, protein-binding properties and type of dialysis65. In general, medicines that are cleared by dialysis should be given after dialysis to avoid under-dosing38. For example, meropenem, an intravenous antibiotic, which has a low affinity for plasma protein-binding, will be easier to remove by dialysis when compared to flucloxacillin, which can be up to 95% protein bound.

HD itself can provide opportunity for intravenous medicines administration on a three-times-weekly schedule, such as erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, antimicrobials and treatments for renal bone disease, which removes the need for cannulation38.

The drug’s stability in the PD dialysis solution and its potential to degrade or lose potency during dialysis requires additional consideration. For example, stability and compatibility of antimicrobials added to PD dialysis solution for the treatment of PD peritonitis is one of the factors that influence treatment success51.

The evidence base for drug efficacy and safety in ESRD patients is limited owing to their frequent exclusion from clinical trials. In this context, pharmacists play an important role in ensuring medicines safety and contributing to the growing body of observational evidence to improve evidence-based practice. The Renal Drug Database is a specialist resource developed by renal pharmacists to assist healthcare professionals in the safe prescribing in patients with renal impairment of those undergoing RRT. The Renal Drug Database also provides information on vital pharmacokinetic changes seen for individual drugs in ESRD. The database can be accessed here66.

Management of conditions associated with ERSD

Anaemia is a common complication in ESRD, which can be attributed to a combination of iron deficiency and/or erythropoietin deficiency. UKKA recommends correcting other causes of anaemia, including iron deficiency anaemia, prior to treatment with erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESAs)67. In ESRD, there is a poor absorption of oral iron owing to chronically elevated concentrations of hepcidin68. Additionally, patient adherence to oral iron therapy remains a struggle owing to gastrointestinal side effects.

This, combined with additional losses of iron from the dialysis circuit and gastrointestinal bleeding, makes IV iron favourable in HD patients67. Pharmacists can optimise iron and ESA therapy, ensuring appropriate dosing, administration and monitoring, while minimising adverse effects associated with anaemia therapies.

Renal mineral bone disease is caused by dysregulation of calcium, phosphate and parathyroid hormone (PTH) in ESRD, manifesting most commonly as secondary hyperparathyroidism. Hypocalcaemia occurring from impaired renal activation of vitamins D is managed with activated vitamin D analogues that do not require renal activation, such as alfacalcidol and calcitriol. Excess parathyroid hormone (PTH) release in response to this hypocalcaemia leads to calcium resorption from bones, which increases the risk of fragility fractures and is conventionally managed by calcimimetics, such as cinacalcet. Pharmacological treatment of hyperphosphatemia is limited to oral phosphate binders, which should be taken with meals to optimise efficacy and should be separated from other medicines to prevent drug interactions. Pharmacists play a role in the counselling and monitoring of renal mineral bone disease therapies. If adherence is a concern, IV treatment regimens administered on HD can be utilised69,70.

Conclusion

A well-structure approach to the care of ESRD patients, incorporating early planning, individualised dialysis modality selection and optimised pharmacological management is crucial for improving outcomes. The contributions of pharmacy teams in ensuring safe medicines use, reducing polypharmacy risks and supporting medicines adherence are vital steps in the management of these patients. Enhanced multidisciplinary collaboration will continue to drive improvements in RRT and overall patient quality of life.

Best practice points

- Identifying dialysis modalities and associated therapies is an important step in the medicine’s reconciliation process for patients on RRT;

- Not all functions of the kidney are replaced by RRT, and these functions often need pharmacological intervention;

- The choice of dialysis modality is dependent on multiple clinical and social factors and patients should be empowered to choose;

- Healthcare professionals should use specialist resources, such as the Renal Drug Database to guide medicines dosing in various degrees of renal impairment.

- 1.Kovesdy CP. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney International Supplements. 2022;12(1):7-11. doi:10.1016/j.kisu.2021.11.003

- 2.Kidney disease: A UK public health emergency – The health economics of kidney disease to 2033. Kidney Research UK. June 2023. https://www.kidneyresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Economics-of-Kidney-Disease-full-report_accessible.pdf?_gl=1*lfhu1f*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTYzNTAyMzI2Mi4xNzMxMzI5Mjcz*_ga_737HY1XF35*MTczMTMyOTI3MS4xLjAuMTczMTMyOTI3MS4wLjAuMA

- 3.Kerr M, Bray B, Medcalf J, O’Donoghue DJ, Matthews B. Estimating the financial cost of chronic kidney disease to the NHS in England. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2012;27(suppl_3):iii73-iii80. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfs269

- 4.Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016–40 for 195 countries and territories. The Lancet. 2018;392(10159):2052-2090. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31694-5

- 5.CKD staging. The UK Kidney Association. https://ukkidney.org/health-professionals/information-resources/uk-eckd-guide/ckd-staging

- 6.Stevens PE, Ahmed SB, Carrero JJ, et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International. 2024;105(4):S117-S314. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018

- 7.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease and Mortality Risk. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;17(7):2034-2047. doi:10.1681/asn.2005101085

- 8.Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic Kidney Disease. The Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1238-1252. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32064-5

- 9.Murphy E, Burns A, Murtagh FEM, Rooshenas L, Caskey FJ. The Prepare for Kidney Care Study: prepare for renal dialysis versus responsive management in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2020;36(6):975-982. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfaa209

- 10.Chronic kidney disease: assessment and management. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng203

- 11.Renal replacement therapy and conservative management. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng107

- 12.Mendelssohn DC, Malmberg C, Hamandi B. An integrated review of “unplanned” dialysis initiation: reframing the terminology to “suboptimal” initiation. BMC Nephrol. 2009;10(1). doi:10.1186/1471-2369-10-22

- 13.Roy D, Chowdhury AR, Pande S, Kam JW. Evaluation of unplanned dialysis as a predictor of mortality in elderly dialysis patients: a retrospective data analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1). doi:10.1186/s12882-017-0778-0

- 14.UK Renal Registry 26th Annual Report. UK Kidney Association. 2022. https://ukkidney.org/audit-research/annual-report

- 15.Naylor KL, Kim SJ, McArthur E, Garg AX, McCallum MK, Knoll GA. Mortality in Incident Maintenance Dialysis Patients Versus Incident Solid Organ Cancer Patients: A Population-Based Cohort. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2019;73(6):765-776. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.12.011

- 16.Renal Medicine: National Specialty Report. NHS England – Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT). 2021. https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Renal-Medicine-Sept21k.pdf

- 17.Stack AG, Martin DR. Association of patient autonomy with increased transplantation and survival among new dialysis patients in the United States. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2005;45(4):730-742. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.12.016

- 18.Selgas R, Honda K, López-Cabrera M, Hamada C, Gotloib L. Peritoneal Structure and Changes as a Dialysis Membrane After Peritoneal Dialysis. Nolph and Gokal’s Textbook of Peritoneal Dialysis. Published online 2023:63-117. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-62087-5_39

- 19.Kulkarni M. Essentials of Dialysis. Springer Nature Singapore; 2024. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-2887-9

- 20.Daugirdas JT, Depner TA, Inrig J, et al. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Hemodialysis Adequacy: 2015 Update. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2015;66(5):884-930. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.015

- 21.Clark WR, Lysaght MJ. MEMBRANE SEPARATIONS | Dialysis in Medical Separations. Encyclopedia of Separation Science. Published online 2000:1687-1693. doi:10.1016/b0-12-226770-2/05141-3

- 22.Clinical Practice Guideline: Haemodialysis. UK Kidney Association. 2019. https://www.ukkidney.org/sites/default/files/FINAL-HD-Guideline.pdf

- 23.Vilar E, Farrington K. Haemodialysis. Medicine. 2011;39(7):429-433. doi:10.1016/j.mpmed.2011.04.004

- 24.Chen YA, Ou SM, Lin CC. Influence of Dialysis Membranes on Clinical Outcomes: From History to Innovation. Membranes. 2022;12(2):152. doi:10.3390/membranes12020152

- 25.Ashby D, Borman N, Burton J, et al. Renal Association Clinical Practice Guideline on Haemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1). doi:10.1186/s12882-019-1527-3

- 26.Neri M, Villa G, et al. Nomenclature for renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury: basic principles. Crit Care. 2016;20(1). doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1489-9

- 27.Neirynck N, Vanholder R, Schepers E, Eloot S, Pletinck A, Glorieux G. An update on uremic toxins. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;45(1):139-150. doi:10.1007/s11255-012-0258-1

- 28.Vascular Access for Haemodialysis: Clinical Practice Guideline. UK Kidney Association. 2023. https://www.ukkidney.org/sites/default/files/FINAL%20FORMATTED%20Vascular%20access%20for%20haemodialysis%20April%202023.pdf

- 29.Manuel W. A guide to vascular access in haemodialysis patients. Br J Nurs. 2017;26(14):1-7. doi:10.12968/bjon.2017.26.14.1

- 30.Robbin ML, Greene T, Allon M, et al. Prediction of Arteriovenous Fistula Clinical Maturation from Postoperative Ultrasound Measurements: Findings from the Hemodialysis Fistula Maturation Study. JASN. 2018;29(11):2735-2744. doi:10.1681/asn.2017111225

- 31.jameson MD, Wiegmann TB. Principles, Uses, and Complications of Hemodialysis. Medical Clinics of North America. 1990;74(4):945-960. doi:10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30528-4

- 32.DAVENPORT A. Intradialytic complications during hemodialysis. Hemodialysis International. 2006;10(2):162-167. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4758.2006.00088.x

- 33.Bhandari B, Komanduri S. Dialysis Disequilibrium Syndrome. StatPearls; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559018/

- 34.Kuipers J, Verboom LM, Ipema KJR, et al. The Prevalence of Intradialytic Hypotension in Patients on Conventional Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Am J Nephrol. 2019;49(6):497-506. doi:10.1159/000500877

- 35.Davenport A. Why is Intradialytic Hypotension the Commonest Complication of Outpatient Dialysis Treatments? Kidney International Reports. 2023;8(3):405-418. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2022.10.031

- 36.Davenport A. Intradialytic complications during hemodialysis. National Library of Medicine . April 10, 2006. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16623668/

- 37.Hamrahian SM, Vilayet S, Herberth J, Fülöp T. Prevention of Intradialytic Hypotension in Hemodialysis Patients: Current Challenges and Future Prospects. IJNRD. 2023;Volume 16:173-181. doi:10.2147/ijnrd.s245621

- 38.Lawrence A, Brown E, Levy J. Oxford Handbook of Dialysis. Oxford Medical Handbooks; 2016.

- 39.Perl J, Bargman JM. Peritoneal dialysis: from bench to bedside and bedside to bench. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2016;311(5):F999-F1004. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00012.2016

- 40.Devuyst O, Goffin E. Water and solute transport in peritoneal dialysis: models and clinical applications. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2008;23(7):2120-2123. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn298

- 41.Teitelbaum I. Peritoneal Dialysis. Ingelfinger JR, ed. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1786-1795. doi:10.1056/nejmra2100152

- 42.Blake PG, Jain AK. Urgent Start Peritoneal Dialysis. CJASN. 2018;13(8):1278-1279. doi:10.2215/cjn.02820318

- 43.Woodrow G, Fan SL, Reid C, Denning J, Pyrah AN. Renal Association Clinical Practice Guideline on peritoneal dialysis in adults and children. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1). doi:10.1186/s12882-017-0687-2

- 44.Crabtree JH, Shrestha BM, Chow KM, et al. Creating and Maintaining Optimal Peritoneal Dialysis Access in the Adult Patient: 2019 Update. Perit Dial Int. 2019;39(5):414-436. doi:10.3747/pdi.2018.00232

- 45.Andreoli MCC, Totoli C. Peritoneal Dialysis. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2020;66(suppl 1):s37-s44. doi:10.1590/1806-9282.66.s1.37

- 46.Poulikakos D, Lewis D. Principles of Peritoneal Dialysis. Imaging and Technology in Urology. Published online 2023:459-464. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-26058-2_81

- 47.Reyskens M, Abrahams AC, François K, van Eck van der Sluijs A. Assisted peritoneal dialysis in Europe: a strategy to increase and maintain home dialysis. Clinical Kidney Journal. 2024;17(Supplement_1):i34-i43. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfae078

- 48.Brown EA, Blake PG, Boudville N, et al. International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis practice recommendations: Prescribing high-quality goal-directed peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2020;40(3):244-253. doi:10.1177/0896860819895364

- 49.JOHNSON DW, AGAR J, COLLINS J, et al. Recommendations for the use of icodextrin in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrology. 2003;8(1):1-7. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1797.2003.00117.x

- 50.Sukul N, Zhao J, et al. Patient-reported advantages and disadvantages of peritoneal dialysis: results from the PDOPPS. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1). doi:10.1186/s12882-019-1304-3

- 51.Li PKT, Chow KM, Cho Y, et al. ISPD peritonitis guideline recommendations: 2022 update on prevention and treatment. Perit Dial Int. 2022;42(2):110-153. doi:10.1177/08968608221080586

- 52.Chow KM, Li PKT, Cho Y, et al. ISPD Catheter-related Infection Recommendations: 2023 Update. Perit Dial Int. 2023;43(3):201-219. doi:10.1177/08968608231172740

- 53.Manley HJ, Garvin CG, Drayer DK, et al. Medication prescribing patterns in ambulatory haemodialysis patients: comparisons of USRDS to a large not-for-profit dialysis provider. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2004;19(7):1842-1848. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfh280

- 54.Manyama TL, Tshitake RM, Moloto NB. The role of pharmacists in the renal multidisciplinary team at a tertiary hospital in South Africa: Strategies to increase participation of pharmacists. Health SA Gesondheid. 2020;25. doi:10.4102/hsag.v25i0.1357

- 55.Dyer SA, Nguyen V, Rafie S, Awdishu L. Impact of Medication Reconciliation by a Dialysis Pharmacist. Kidney360. 2022;3(5):922-925. doi:10.34067/kid.0007182021

- 56.Al Raiisi F, Stewart D, Fernandez-Llimos F, Salgado TM, Mohamed MF, Cunningham S. Clinical pharmacy practice in the care of Chronic Kidney Disease patients: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(3):630-666. doi:10.1007/s11096-019-00816-4

- 57.Rapa SF, Di Iorio BR, Campiglia P, Heidland A, Marzocco S. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Chronic Kidney Disease—Potential Therapeutic Role of Minerals, Vitamins and Plant-Derived Metabolites. IJMS. 2019;21(1):263. doi:10.3390/ijms21010263

- 58.Novel potassium binders: a clinical update. Br J Cardiol. Published online 2021. doi:10.5837/bjc.2021.014

- 59.Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, Chu A, Mann S, MacRury M. UKKA Clinical Practice Guideline – Management of Hyperkalaemia in Adults. UK Kidney Association. 2023. https://www.ukkidney.org/sites/default/files/FINAL%20VERSION%20-%20UKKA%20CLINICAL%20PRACTICE%20GUIDELINE%20-%20MANAGEMENT%20OF%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20IN%20ADULTS%20-%20191223_0.pdf

- 60.Usta M, Ersoy A, Ayar Y, et al. Comparison of endoscopic and pathological findings of the upper gastrointestinal tract in transplant candidate patients undergoing hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis treatment: a review of literature. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1). doi:10.1186/s12882-020-02108-w

- 61.Ozmen S, Kaplan MA, Kaya H, et al. Role of lean body mass for estimation of glomerular filtration rate in patients with chronic kidney disease with various body mass indices. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 2009;43(2):171-176. doi:10.1080/00365590802502228

- 62.Lang J, Katz R, Ix JH, et al. Association of serum albumin levels with kidney function decline and incident chronic kidney disease in elders. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2017;33(6):986-992. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfx229

- 63.Trobec K, Kerec Kos M, von Haehling S, Springer J, Anker SD, Lainscak M. Pharmacokinetics of Drugs in Cachectic Patients: A Systematic Review. Wölfl S, ed. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e79603. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079603

- 64.Sehgal AR, Leon J, Soinski JA. Barriers to adequate protein nutrition among hemodialysis patients. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 1998;8(4):179-187. doi:10.1016/s1051-2276(98)90016-4

- 65.Pea F, Viale P, Pavan F, Furlanut M. Pharmacokinetic Considerations for Antimicrobial Therapy in Patients Receiving Renal Replacement Therapy. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 2007;46(12):997-1038. doi:10.2165/00003088-200746120-00003

- 66.The Renal Drug Database. The Renal Drug Database. https://www.renaldrugdatabase.com/s/

- 67.UKKA Anaemia of CKD Guideline. UK Kidney Association. 2024. https://www.ukkidney.org/sites/default/files/FINAL%20VERSION%20-%20%20UKKA%20ANAEMIA%20OF%20CKD%20GUIDELINE%20-%20Sept%202024.pdf

- 68.Gutiérrez OM. Treatment of Iron Deficiency Anemia in CKD and End-Stage Kidney Disease. Kidney International Reports. 2021;6(9):2261-2269. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.05.020

- 69.Murray SL, Wolf M. Calcium and Phosphate Disorders: Core Curriculum 2024. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2024;83(2):241-256. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2023.04.017

- 70.KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention, and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease–Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney International Supplements. 2017;7(1):1-59. doi:10.1016/j.kisu.2017.04.001