Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Recognise the symptoms of iron deficiency and know how the condition is diagnosed;

- Understand the causes and risk factors for developing iron deficiency anaemia;

- Know how to manage and monitor the condition, with particular focus on iron supplementation.

Anaemia is defined as a condition in which either the number of circulating erythrocytes (red blood cells), or the haemoglobin (Hb) concentration contained within them, are below reference range; it is classified based on the size of erythrocytes and the Hb concentration[1].

Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) is described as microcytic (erythrocytes that are smaller than normal, as measured by a low mean cell volume [MCV]) and hypochromic (lower amounts of mean cell Hb)[1].

There are anaemias with different aetiologies, such as anaemia of chronic disease, thalassaemia and sideroblastic anaemia; however, IDA is the most common type of anaemia. Globally, it is reported to affect 1 billion people, where 3% of men and 8% of women in the UK have IDA[1,2]. It is a public health issue seen in both high- and low-income countries, and this article will outline the multifactorial causes. In low- and middle-income countries, lower intake of processed foods or animal products may contribute to a higher prevalence of anaemia[3].

Globally, the highest incidence of anaemia is in children under five years and women of reproductive age (15–49 years)[1]. The UK prevalence is estimated to be 23% in pregnant women and 12% in premenopausal women[2]. In 2019, the global prevalence was 36.5% in pregnant woman and 29.6% in non-pregnant women of reproductive age[4]. The prevalence of anaemia in children aged under 5 years is 15.5% in the UK and 39.8% globally[1]. In comparison, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) estimates the prevalence to be 2–5% in adult men and postmenopausal females in high income countries[2].

Iron plays a pivotal role in the function of various cellular mechanisms; it is an essential component of haemoglobin and myoglobin — an oxygen-binding protein found exclusively in cardiac and muscle cells — that contains around 60% of the total body iron[5].

Iron is involved in production of erythrocytes in bone marrow and is vital for oxygen binding to Hb. IDA occurs when fewer erythrocytes are produced as a result of low iron stores[6]. Iron is stored as ferritin and hemosiderin in liver, spleen, marrow, duodenum and skeletal muscle[7]. A typical western diet contains around 15mg of iron daily, of which 10% (1–2mg) is absorbed; however, 20–25mg of iron is required daily for erythrocyte production[5]. Iron sources are obtained from iron stores, as well as recycled from aged erythrocytes that have a lifecycle of 120 days within the circulation[8].

Pharmacists have a role in the management of IDA to ensure patients are educated on their iron replacement therapy for optimal effect, and can also advise on side effect management. Pharmacists should be aware of differential diagnosis, treatment selection, dosing and monitoring of different iron preparations, all of which are described below.

Signs and symptoms

IDA is commonly seen in general practice, and symptoms are dependent on how rapidly it develops and its severity[9]. In chronic IDA or slow blood loss, patients can often tolerate markedly low levels of Hb, with minimal symptoms, owing to haemodynamic compensatory mechanisms maintaining adequate oxygen delivery[10].

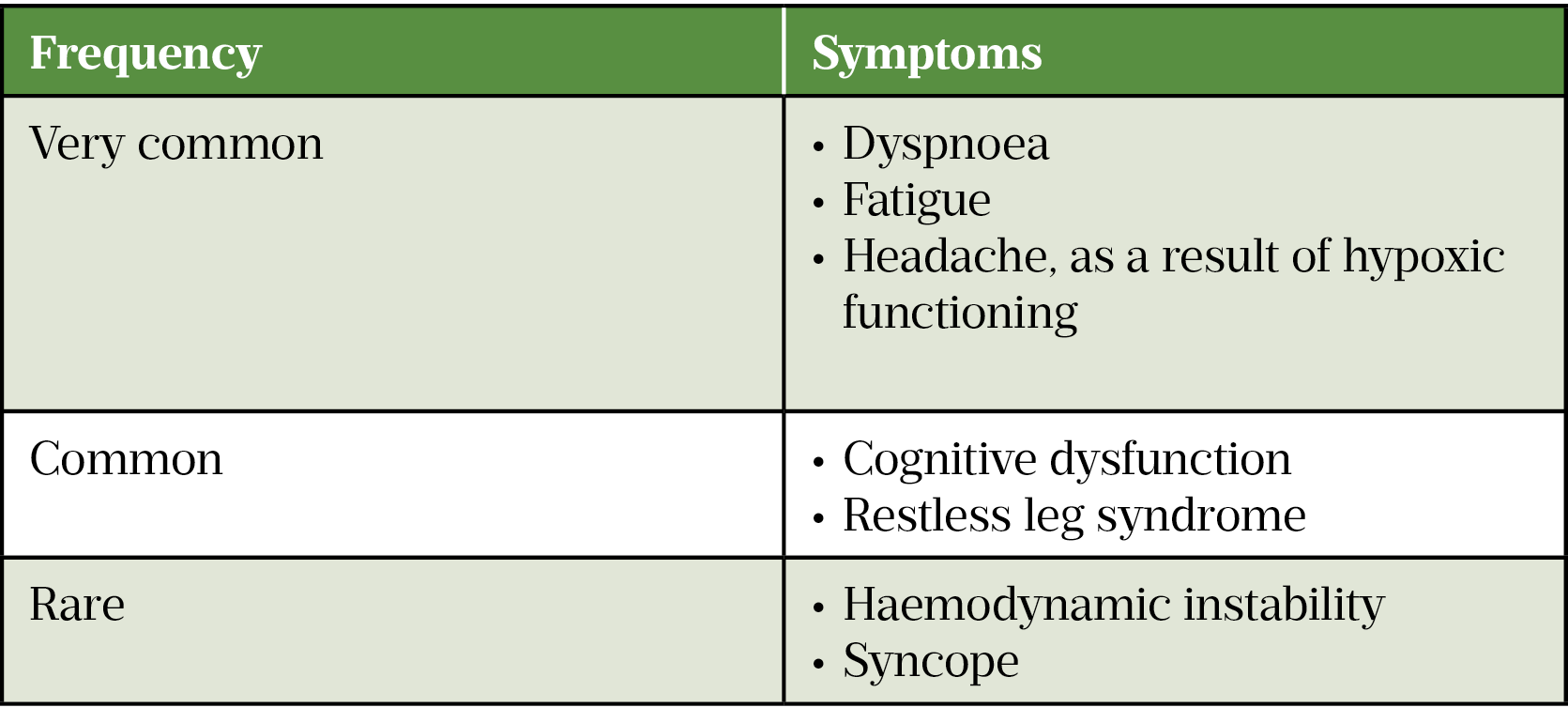

Patients with anaemia may present with non-specific symptoms, such as those listed in Table 1. Children may present with reduced appetite[11].

Other symptoms of anaemia include:

- Dizziness;

- Weakness;

- Irritability;

- Palpitations;

- Pica (unusual dietary craving — for example, ice or dirt)[2,12].

Patients with mild-to-moderate IDA may be asymptomatic. Some common symptoms of IDA include:

- Pallor (pale skin);

- Atrophic glossitis (inflammation of the tongue);

- Dry and rough skin;

- Dry and damaged hair;

- Alopecia (hair loss)[2].

Another common sign of IDA is angular cheilosis (ulceration of the corners of the mouth). Changes to the nails, such as koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails), are a rare symptom of IDA[2].

Severe symptoms, such as tachycardia or signs of worsening of pre-existing heart failure (e.g. ankle oedema or dyspnoea at rest), would require immediate treatment[2,12].

Causes and risk factors

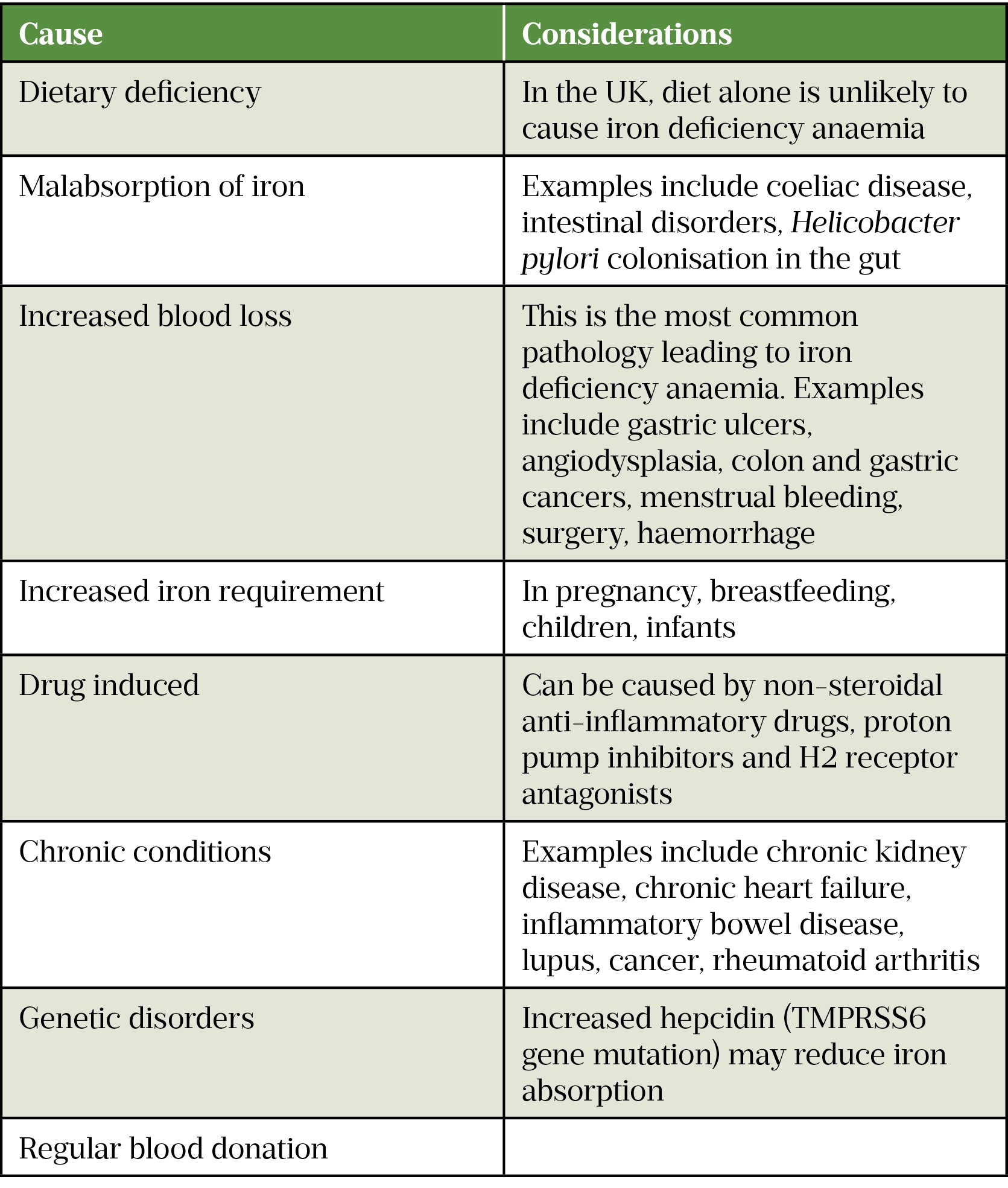

The risk of developing IDA can be multifactorial; causes are shown in Table 2.

Additionally, infants, particularly with a history of prematurity, can be at risk of IDA owing to growth spurts utilising the iron stores accumulated during gestation[5].

Iron requirements in pregnancy are elevated owing to increased maternal erythrocyte production for growth of the placenta and fetus[9]. Menstruation is the most common cause of IDA in pre-menopausal women[2].

Environmental factors, such as exposure to contaminated water leading to parasitic infections of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (e.g. whipworm and hookworm, which can be picked up when travelling in low-income countries), can cause IDA[9]. Athletes can also experience IDA owing to haemolysis (i.e. breakdown of erythrocytes)[13].

Diagnosis

A thorough clinical history should be taken when IDA is suspected. A physical examination should include an assessment of the skin, tongue, nails, eyelids and heart rate. Questions that can aid diagnosis are shown in Box 1. Medication history should be reviewed, including use of over-the-counter medicines. Exploration of rectal bleeding can reveal a range of causes, from signs of haemorrhoids to carcinoma of the GI tract. Examples of GI symptoms include pain, cramps, swelling of the abdomen and melena[14]. For pre-menopausal women, prolonged or abnormally heavy menstruation is indicative of IDA[15].

Box 1: Questions to ask as part of an iron deficiency anaemia assessment

- Have you experienced heavy bleeding or bruising?

- Do you have any shortness of breath?

- Have you experienced any chest pain, palpitations or ankle swelling?

- Are you experiencing tiredness?

- What does your diet consist of?

- Are you currently taking any medication?

- Do you have a history of blood donation?

- Have you travelled abroad recently?

For IDA diagnosis, a full blood count should be requested. In instances where both Hb and MCV are low, a ferritin level will confirm diagnosis of IDA. Hb levels for hypochromia diagnosis are dependent on gender and age, and are classified as follows:

- In children aged 3–6 months: Hb 95g/L

- In children aged 6 months to 2 years: Hb 105g/L

- In children aged 2–11 years: Hb <115g/L

- In children aged 12–14 years: Hb <120g/L

- In men aged over 15 years: Hb <130g/L

- In non-pregnant women aged over 15 years: Hb <120g/L

- In pregnant women: Hb <110g/L throughout pregnancy:

- Hb >110g/L appears adequate in the first trimester; Hb of 105g/L appears adequate in the second and third trimesters.

- Hb levels in pregnancy are reduce owing to haemodilution, whereby the red cell mass and plasma volume both increase.

- Postpartum: below 100g/L[15,16]

The reference range for Hb is 135–175g/L in males and 115–160g/L in females[15].

Microcytosis is classified as MCV less than 80 femtolitres[2]. The reference range for MCV is 80–96 femtolitres[15]. It should be noted that MCV alone cannot be used to diagnose IDA; although the lower the value, the higher the likelihood of IDA. For example, an MCV<75 femtolitres will only identify 68% of people with IDA[2].

Serum ferritin tests are indicative of iron stores. The reference range for ferritin is 30–300 micrograms/L in males and 15–200 micrograms/L in females[15]. Ferritin levels less than 30 micrograms/L would confirm IDA diagnosis. The sensitivity and specificity of the ferritin test is 92% and 98%, respectively[17]. Serum ferritin is less reliable in pregnancy as it is expected to be low in the second and third trimester owing to increased demand for iron.

Other conditions that may affect serum ferritin are those with ongoing inflammation, such as rheumatoid arthritis and irritable bowel syndrome, or infection, where serum ferritin levels are raised as part of an immune response. Increased ferritin levels have also been observed in liver disease[15,18].

Very low ferritin is a reliable predictor for IDA, whereas normal, or elevated, ferritin is not a reliable predictor for iron repletion when there is concurrent inflammation. In both acute and chronic inflammation states, increased ferritin levels can be falsely elevated and therefore independent of iron levels. IDA can be present when ferritin levels are >50micrograms/L, which can make diagnosis difficult; therefore, further tests would be required to facilitate interpretation of results, such as the level of C-reactive protein, which is raised in inflammatory conditions[2]. Other more specific tests include total iron binding capacity (TIBC) and transferrin saturation[19]. TIBC measures the blood ability to attach itself to iron. In IDA, serum iron falls and TIBC raises, whereas transferrin substantially reduces in IDA, which is the ratio of serum iron to TIBC[15]. Raised reticulocyte (i.e. young erythrocytes) haemoglobin is also a strong predictor of IDA. It can be used for difficult-to-diagnose cases and is useful when ferritin is raised[20].

Deficiency of iron, vitamin B12 and folate can occur in the presence of small bowel disease and therefore all should be checked and corrected.

When an IDA diagnosis is made for men and postmenopausal women, without any obvious blood loss, upper and lower GI investigations should be considered to rule out malignancy or peptic ulcer disease[21].

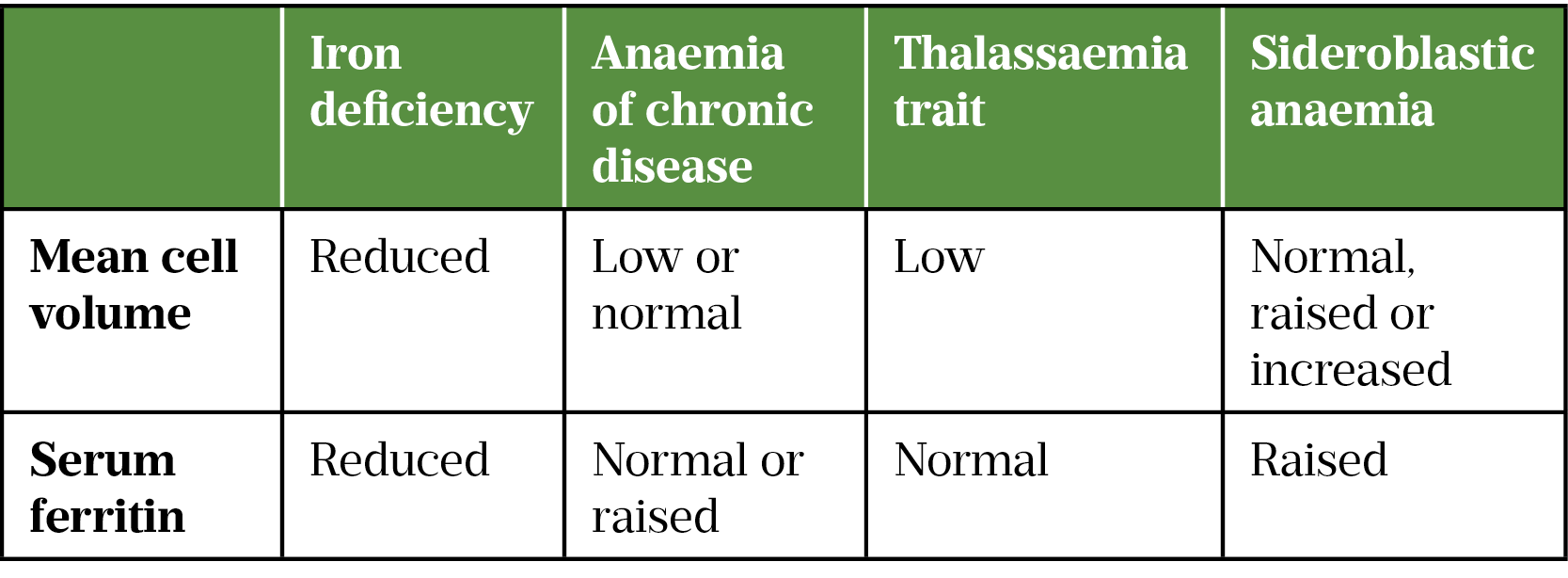

Differential diagnosis

Microcytosis and hypochromia can also occur in other anaemias of chronic disease (e.g. chronic inflammatory diseases, rheumatoid arthritis and malignant diseases) and haemoglobinopathies, such as thalassaemia and sideroblastic anaemia[15].

Most patients with anaemia of chronic disease are normocytic and normochromic; microcytosis and hypochromia are seen in around 20% of cases[2]. Ferritin levels remain within reference range in anaemia of chronic disease and thalassaemia, in comparison to IDA. Sideroblastic anaemia, in which ferritin levels are raised, is a rare anaemia that can be inherited or acquired.[22]. Hepatosplenomegaly is a feature in one-third to one-half of sideroblastic anaemia patients and is not seen in IDA[2].

Management

Initial management of IDA aims to identify the underlying cause and treat it, alongside correcting anaemia with iron replacement therapy[21]. Several factors can lead to treatment failure, such as malabsorption (e.g. in the case of coeliac disease), the underlying cause not being corrected or the presence of another anaemia[15]. Lack of adherence to oral iron therapy caused by side effects and multiple daily dosing can also contribute to ongoing symptoms of IDA.

Onward referrals should be made to the wider multidisciplinary teams as appropriate; for example, referrals should be made to dieticians for dietary support and advice. Suspected gastrointestinal tract (lower) cancer pathways should be used for patients based on symptoms, age and other complications, a comprehensive list can be accessed using the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary: ‘Referral for suspected gastrointestinal tract (lower) cancer[23]. Gastroenterology referrals should be made when GI bleeds are suspected. Gynaecology referrals should be made for menorrhagia concerns. Haematology referrals should be made for ongoing anaemia not responding to therapy. A comprehensive list of when and who to refer someone with iron deficiency anaemia can be accessed using the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary: ‘Management of iron deficiency anaemia’[2].

Lifestyle changes

Patients diagnosed with IDA can be advised to make changes to their diet by eating iron rich foods, such as leafy vegetables (watercress and kale), meat, dried fruit (apricots, prunes and raisins) and pulses (beans, peas and lentils). Tea, coffee, milk and dairy products should be reduced as they can impact iron absorption[24]. The World Health Organization recommends fortification of complementary foods with iron-containing micronutrient powders in infants and young children aged 6–23 months[25].

Oral iron replacement

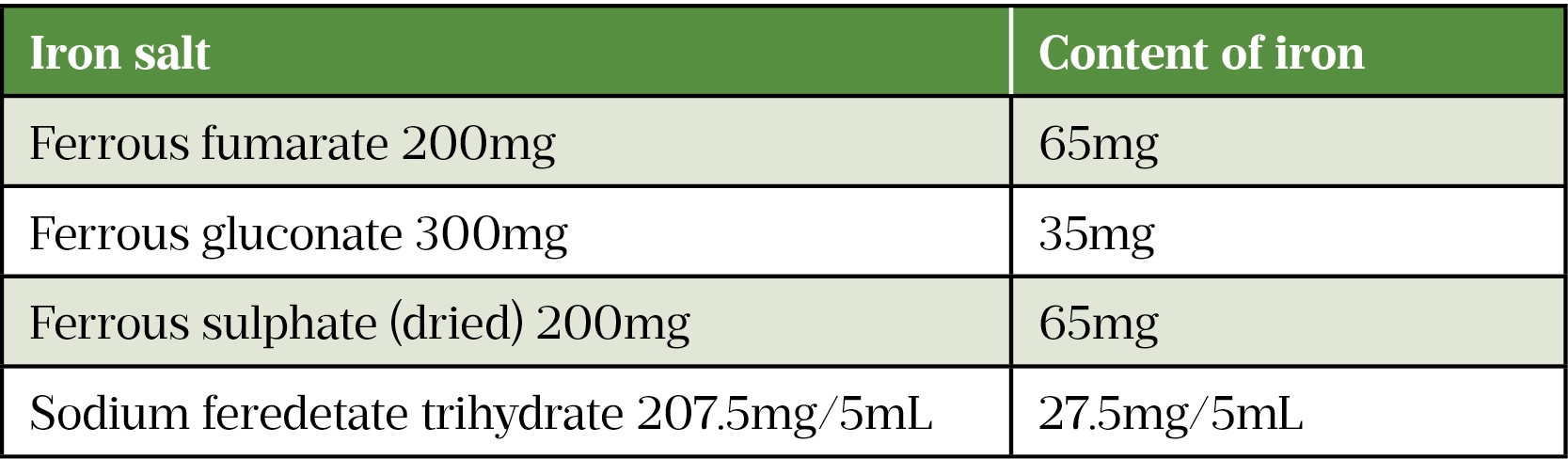

There are several oral iron salt preparations available, containing varying degrees of elemental iron, as shown in Table 4. When starting therapy, lower doses of iron are recommentded as this may be just as effective and likely associated with a lower rate of adverse effects. NICE guidelines therefore state that a once-daily dose of 65mg elemental iron (e.g. ferrous sulphate 200mg daily) is sufficient for treating IDA[2].

It should be noted that bioavailability of iron preparations can vary significantly between individuals and is markedly decreased by consumption with food. It is suggested that absorption can vary from 2–28%[26]. There are minimal differences in efficacy and iron absorption of the different ferrous salts[27].

Side effects

Patients should be counselled on the side effects of oral iron therapy, which include abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting (usually dose related), constipation, diarrhoea and a metallic taste[28]. Box 2 outlines some approaches to minimise side effects.

Box 2: Approaches to minimise side effects of oral iron therapy

- Iron is best absorbed on an empty stomach but can be taken with meals to minimise GI disturbances;

- Reduce the frequency of dosing to alternate days[2,6].

Modified release preparations, available as once-daily doses, are usually more expensive and release iron past the optimal site of absorption; therefore, they are not recommended by NICE[2,27]. Liquid preparations are also available for children or patients with swallowing difficulties.

Frequency of side effects usually reduces over time; the importance of adherence should be stressed and reason/s for non-adherence should be explored. Patients are likely to have dark stools and should be informed that this is not harmful. Tannins (found in tea, coffee), zinc supplements and antacids reduce iron absorption and should be avoided where possible. Conversely, iron reduces the absorption of certain drugs, such as tetracyclines and quinolones. In instances where both medicines are administered, they should be taken anything from one to six hours apart, depending on the agent and the individual’s assessment. Food rich in vitamin C (e.g. oranges and tomatoes) may increase absorption of iron[27,29]. Combination preparations are available containing iron and ascorbic acid; however, therapeutic advantage is minimal and increases cost[27].

Monitoring

When the cause is addressed, Hb can increase by 10g/L per week with iron therapy. The duration of therapy is dependent on the time taken to correct Hb levels. As per NICE guidance, Hb is expected to rise 20g/L over 3–4 weeks; therefore, it is recommended to recheck the full blood count (FBC) within 4 weeks after starting therapy[2]. If there is an adequate response, a FBC should be repeated at 2–4 months to ensure Hb has returned to normal. Once normalised, therapy should then be continued for a further 3 months to replenish iron stores. Further monitoring is required periodically for example at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months[2]. Certain patient groups would benefit from oral iron at preventative doses (e.g. ferrous sulphate 200mg daily), such as in reoccurring anaemia, poor diet, malabsorption, menorrhagia, in pregnancy, cancer and after a gastrectomy[27].

Parenteral iron preparations

Parenteral iron preparations can be used for patients who: cannot tolerate oral iron; have iron losses greater than that which can be absorbed daily using oral agents; are severely anaemic; peri-operative; or in haemodialysis[30]. In comparison to oral iron, parenteral iron preparations produce rapid responses and better iron replenishment[31]. It is recommended that Hb is assessed no earlier than four weeks after the final administration of intravenous (IV) preparation to allow adequate time for erythropoiesis and iron utilisation[32].

Parenteral iron preparations available in the UK include iron dextran, iron sucrose, ferric derisomaltose and ferric carboxymaltose. All are administered intravenously, with the exception of iron dextran, which can also be administered via the intramuscular route. They all can be administered during haemodialysis, using the venous line of the dialysis machine.

A method of calculating the dose of the parenteral iron is the Ganzoni formula, which is:

Total iron deficit (mg) = body weight (kg) x (target Hb – actual Hb) (g/dL) x 2.4 + iron stores (mg)[33]

When using this equation, it is recommended to use the patient’s ideal body weight for obese patients, or pre-pregnancy weight for pregnant women. For a person with a body weight of ≥35kg, the iron stores are 500mg and for body weight <35kg, the iron stores are 15mg/kg[34]. Alternatively, the summary of product characteristics for each drug has a tabulated dose based on patient weight and Hb, for ease of calculation. Guidance for rates of administration can be found here.

All IV iron preparations carry a risk of serious hypersensitivity reaction, which is rare but fatal if not treated immediately. Hypersensitivity reactions include serious and potentially fatal anaphylaxis, characterised by sudden onset of respiratory difficulty and/or cardiovascular collapse. Less severe reactions include urticaria and itching[35]. Measures to minimise risk should therefore be put in place. Parenteral iron preparations must be administered under close medical supervision during the injection/infusion and for 30 minutes after every administration, where full resuscitation facilities are available. If such a serious reaction occurs, treatment should be stopped immediately and appropriate management initiated; this is beyond the scope of this article, more detail can be found here. Allergies, immune or inflammatory conditions, a history of severe asthma, eczema or other atopic allergy, and rapid infusion all predispose patients to hypersensitivity[35]. It should be noted that patients can still react to IV iron even if they have tolerated it previously.

Additionally, in pregnancy, use of these preparations should be confined to the second and third trimester, and only used if the benefits of the treatment are outweighed by the risks to the foetus, such as anoxia and foetal distress[36].

In severe cases of IDA, blood transfusion can be offered when a rapid rise in Hb is required[6]. An alternative option for patients with cancer or chronic kidney disease (CKD) is erythropoietin-stimulating agents. Erythropoietin is a hormone produced by the kidney, which stimulates the bone marrow to create erythrocytes. However, in CKD, anaemia is largely caused by deficiency of this hormone[37].

Complications

Mild cases of IDA do not cause complications. However, IDA can become severe, leading to severe complications, such as tachycardia, chest pains and irregular heartbeat leading to heart failure. Heart failure can occur in those with a haemoglobin level less than 50g/L[2].

In a study of athletes, it was found that IDA can reduce muscular performance, impair endurance and exercise capacity[38].

IDA can result in a reduction in productivity in adults and negatively effects cognitive and physical development in children[6].

IDA in pregnancy and children is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, as these are vulnerable patient groups. Numerous observational studies have demonstrated a correlation in maternal anaemia and neurodevelopment impairment, including impaired motor cognition and language development in the neonate[39]. A UK observational study conducted in 2014 found that 60% of pregnant women with maternal anaemia with Hb <85g/L sustained postpartum haemorrhage[40]. Maternal anaemia has also been associated with perinatal and neonatal mortality, low birth weight and pre-term birth[40]. It is therefore vital that Hb is measured around 10 weeks of pregnancy and repeated at 28 weeks. If IDA is diagnosed, treatment should be started promptly. Otherwise, preventative therapy can be commenced in at-risk patients identified[38].

IDA can also lead to impaired immunity causing increased risk of infections[14].

Summary

IDA is a public health problem, with pre-menopausal women most affected. Pharmacists have an opportunity to improve the diagnosis and treatment of IDA in clinical practice by understanding the monitoring requirements. Knowing when to escalate therapy or carry out further investigations is essential for optimal treatment, as well as being able to offer the range of iron preparations.

This article was amended on 11 April 2022 to reflect National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance. It was then reviewed and updated by the expert authors in April 2024 to ensure it remains relevant, following its original publication in February 2022.

- 1McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, et al. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993–2005. PHN. 2008;12:444. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980008002401

- 2Anaemia — iron deficiency. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/anaemia-iron-deficiency/ (accessed April 2022)

- 3Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Özaltin E, et al. Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. 2011;378:2123–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62304-5

- 4Anaemia in women and children. World Health Organization. 2021. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/anaemia_in_women_and_children

- 5Lopez A, Cacoub P, Macdougall IC, et al. Iron deficiency anaemia. The Lancet. 2016;387:907–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60865-0

- 6Miller JL. Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Common and Curable Disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2013;3:a011866–a011866. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a011866

- 7Saito H. METABOLISM OF IRON STORES. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014;76:235–54.

- 8Steinbicker A, Muckenthaler M. Out of Balance—Systemic Iron Homeostasis in Iron-Related Disorders. Nutrients. 2013;5:3034–61. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5083034

- 9Yip R, Ramakrishnan U. Experiences and Challenges in Developing Countries. The Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132:827S-830S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/132.4.827s

- 10Hegde N, Rich M, Gayomali C. The cardiomyopathy of iron deficiency. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33:340–4.

- 11Ghrayeb H, Elias M, Nashashibi J, et al. Appetite and ghrelin levels in iron deficiency anemia and the effect of parenteral iron therapy: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0234209. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234209

- 12Provan D, editor. ABC of Haematology. 4th ed. London: BMJ 2018.

- 13Camaschella C. Iron-Deficiency Anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1832–43. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1401038

- 14Gasche C. Iron, anaemia, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2004;53:1190–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2003.035758

- 15Kumar P, Clark M. Kumar and Clark’s Clinical Medicine. 9th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier 2017.

- 16Wang M. Iron Deficiency and Other Types of Anemia in Infants and Children. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93:270–8.

- 17Mast AE, Blinder MA, Gronowski AM, et al. Clinical utility of the soluble transferrin receptor and comparison with serum ferritin in several populations. Clinical Chemistry. 1998;44:45–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/44.1.45

- 18Barragán-Ibañez G, Santoyo-Sánchez A, Ramos-Peñafiel CO. Iron deficiency anaemia. Revista Médica del Hospital General de México. 2016;79:88–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hgmx.2015.06.008

- 19Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity . World Health Organization. 2011. https://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin.pdf (accessed February 2022)

- 20Brugnara C. Reticulocyte Hemoglobin Content to Diagnose Iron Deficiency in Children. JAMA. 1999;281:2225. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.23.2225

- 21Goddard AF, James MW, McIntyre AS, et al. Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. Gut. 2011;60:1309–16. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.228874

- 22Meredith JL, Rosenthal NS. Differential Diagnosis of Microcytic Anemias. Lab Med. 1999;30:538–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/30.8.538

- 23Clinical knowledge summary: Gastrointestinal tract (lower) cancers — recognition and referral. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/gastrointestinal-tract-lower-cancers-recognition-referral/ (accessed April 2024)

- 24Iron deficiency anaemia. NHS. 2021. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/iron-deficiency-anaemia/ (accessed April 2024)

- 25WHO guideline: Use of multiple micronutrient powders for point-of-use fortification of foods and consumed by infants and young children aged 6–23 months and children aged 2–12 years. World Health Organization. 2016. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549943 (accessed February 2022)

- 26Stoffel NU, von Siebenthal HK, Moretti D, et al. Oral iron supplementation in iron-deficient women: How much and how often? Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2020;75:100865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2020.100865

- 27Anaemia, iron deficiency. British National Formulary. 2021. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/anaemia-iron-deficiency.html (accessed February 2022)

- 28Ferrous sulphate 200mg coated tablets. Electronic medicines compendium. 2017. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3130/smpc (accessed February 2022)

- 29HALLBERG L, BRUNE M, ROSSANDER-HULTHÉN L. Is There a Physiological Role of Vitamin C in Iron Absorption? Ann NY Acad Sci. 1987;498:324–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb23771.x

- 30Parenteral iron. Joint United Kingdom (UK) Blood Transfusion and Tissue Transplantation Services Professional Advisory Committee. 2014. https://www.transfusionguidelines.org/transfusion-handbook/6-alternatives-and-adjuncts-to-blood-transfusion/6-4-parenteral-iron (accessed February 2022)

- 31Ferinject (ferric carboxymaltose). Electronic medicines compendium. 2020. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5910 (accessed February 2022)

- 32Schaefer B, Meindl E, Wagner S, et al. Intravenous iron supplementation therapy. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2020;75:100862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2020.100862

- 33Ganzoni equation for iron deficiency anemia. MD Calc. 2022. https://www.mdcalc.com/ganzoni-equation-iron-deficiency-anemia (accessed February 2022)

- 34Intravenous iron and serious hypersensitivity reactions: strengthen recommendations. Medicine and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2014. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/intravenous-iron-and-serious-hypersensitivity-reactions-strengthened-recommendations (accessed February 2022)

- 35New recommendations to manage risk of allergic reactions with intravenous iron-containing medicines. European Medicines Agency. 2013. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/ document_library/Press_release/2013/06/WC500144874.pdf (accessed February 2022)

- 36Anaemia of chronic disease — approach. BMJ Best Practice. 2018. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/95 (accessed February 2022)

- 37Beard J, Tobin B. Iron status and exercise. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;72:594S-597S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/72.2.594s

- 38Pavord S, Myers B, Robinson S, et al. UK guidelines on the management of iron deficiency in pregnancy. British Journal of Haematology. 2012;156:588–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.09012.x

- 39Briley A, Seed P, Tydeman G, et al. Reporting errors, incidence and risk factors for postpartum haemorrhage and progression to severe PPH : a prospective observational study. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy. 2014;121:876–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12588

- 40Rahman MM, Abe SK, Rahman MS, et al. Maternal anemia and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis1,2. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016;103:495–504. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.107896

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

NICE 2021 has updated guidance on the recommended dosing or iron. There is now a recommendation that once daily oral iron (50-100mg elemental iron) is sufficient (not 100-200mg elemental iron as this paper suggests). This is due to hepcidin, which regulates iron uptake. Multiple daily dosing of iron increases the production of hepcidin, which reduces the amount of iron uptake. Hence, multiple daily dosing does not necessarily confer increased iron absorption but may lead to increased side effects.

This is taken from the updated NICE guidance:-

Traditionally oral iron salts were taken as split dose, two or three times a day. More recent data suggest that lower doses and more infrequent administration may be just as effective, while probably associated with lower rates of adverse effects.

The optimal drug, dosage and timing of oral iron for adults with iron deficiency anaemia are not clearly defined, and the effect of alternate day therapy on compliance and ultimate haematological response are unclear. Based on the available literature, a once daily dose of 50-100 mg of elemental iron (for example, one ferrous sulfate 200 mg tablet a day) taken in the fasting state may be the best compromise option for initial treatment.