Science Photo Library

Menorrhagia, also known as heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), is widely accepted as the loss of menstrual blood of ≥60–80ml per cycle, compared with 30–40ml for the average woman with ‘normal’ periods[1]

,[2]

. Menstrual blood volume is impractical to measure; therefore, it is usual to make an assessment based on information from the patient. Women with HMB may describe having to use both tampons and sanitary towels, having to frequently change sanitary towels, and/or the presence of large menstrual clots. These can negatively impact activities of daily living (e.g. avoiding playing sports or going out). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) defines HMB more holistically as “excessive blood loss that interferes with the woman’s physical, emotional, social and material quality of life”[3]

.

Prevalence

HMB increases with age, affecting 25% of women aged 30–50 years[2],[4]

. Furthermore, of 1.2 million referrals to specialist gynaecologist services, around 20% are for HMB[4]

.

Each year in England and Wales around 40% of women who are referred to specialists after experiencing HMB for the first time require surgical intervention[5]

. A national audit of HMB conducted by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) found that on first presentation to gynaecological outpatients, almost 50% of women had concomitant issues, such as fibroids, endometriosis and/or polyps, with nearly a third reporting that they had received no previous treatment in primary care[4]

. This may or may not be owing to immediate referral being an appropriate option (e.g. for women with extensive fibroids)[4]

.

By the age of 60 years, 20% of women in the UK will have had a hysterectomy, mainly for heavy bleeding, even though histologically 40% of these women will have a normal uterus on examination[2],[6]

.

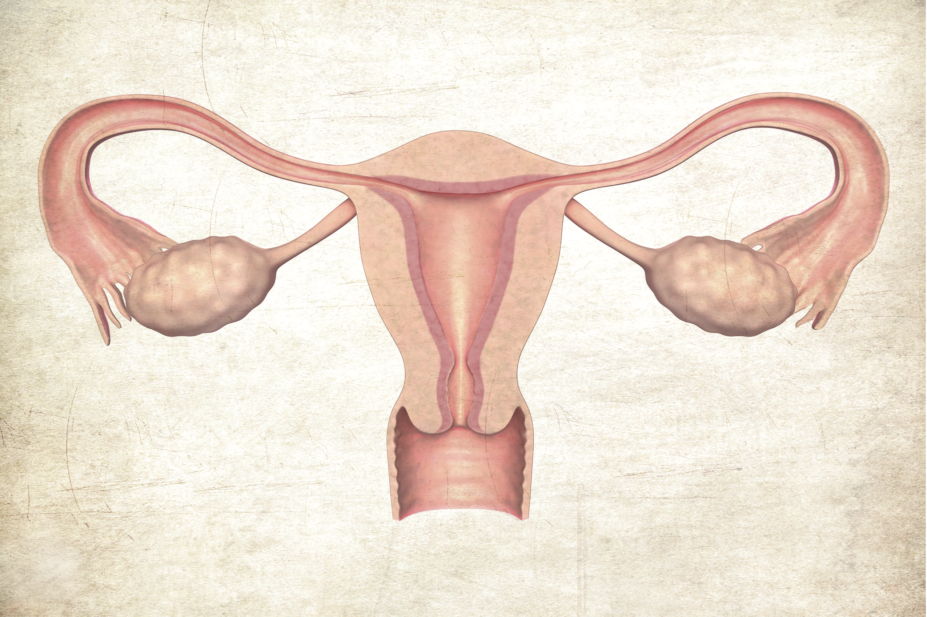

Pathophysiology

During menstruation, oestrogen and progesterone released from the ovaries results in the production of prostaglandins (PGs), cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases, which are responsible for the cyclical regeneration of the functional layer of the endometrium[2]

. Disruption of the complex processes at play results in abnormal uterine bleeding[2]

.

Women with HMB are often found to have:

- A disturbance in the endometrial coagulation process;

- Shifts in PG secretion from vasoconstrictory (PGF2α) to vasodilatory PGs (PGE2, PGI2);

- Thinning of the vascular smooth muscle cell layer of the spiral arterioles[2],[7]

.

PGI2 (prostacyclin) also has a role in preventing platelet aggregation. An increase in PGE2 and PGI2 receptors have been shown in women with menorrhagia[8]

.

Other conditions associated with HMB

Although there is no identifiable cause of HMB in more than half of cases, HMB can be a result of other underlying disorders[8],[9]

(see Box 1). HMB is not usually considered a life-threatening condition; however, patients who present with symptomatic anaemia, abnormal coagulation profiles or current haemorrhage require urgent medical attention[2]

.

Box 1: Possible underlying conditions causing heavy menstrual bleeding[2],[9]

Abnormal menstrual bleeding can be symptomatic of another underlying condition, including:

- Choriocarcinoma;

- Chronic renal/hepatic disease;

- Ectopic pregnancy;

- Endometrial polyps;

- Endometriosis;

- Endometritis;

- Hypothyroidism;

- Miscarriage;

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS);

- Salpingitis/pelvic inflammatory disease (PID);

- Uterine/cervical malignancy;

- Uterine fibroids;

- von Willebrand disease.

Iatrogenic causes include intrauterine contraceptive devices, tubal ligation, anticoagulants, tamoxifen and exogenous oestrogens[9],[10]

. It is important to remember that herbal remedies, such as ginseng, ginkgo and soya, can alter oestrogen levels and coagulation parameters, leading to menstrual irregularities[2]

.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common cause of anovulation in women of reproductive age. The resultant unapposed oestrogen causes endometrial hyperplagia, which often leads to HMB. Other causes of anovulation include hyperprolactinaemia, hypothyroidism, hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis dysfunction, and dysfunction of the corpus luteum owing to inadequate production of progesterone[2],[11]

.

Diagnosis

Obtaining a detailed history from the patient is the best way to diagnose HMB (see Table 1), with physical examinations (see Table 2) and tests (see Table 3) performed to exclude more serious conditions.

History

History-taking should include questions on the nature of the bleeding, the patient’s perspective on whether this variation falls within normal fluctuations in their cycle and blood loss, and how it is affecting their quality of life, as well as questions on their medical history (see Table 1).

Women aged 55 years and over who have post-menopausal bleeding should be referred using a suspected cancer pathway referral for an appointment within two weeks as per NICE guidelines.

| History-taking questions | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Age and cycle regularity | Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) can be associated with irregular cycles because of anovulation in the first year of menstruation and during perimenopause |

| Gravidity (number of pregnancies) | There is a correlation between endometrial adenomyosis and multiple pregnancies |

| Fatigue, dyspnoea on exertion and orthostatic symptoms | These can be indicative of anaemia |

| Intolerance to cold, hair and skin changes, weight gain | These are suggestive of hypothyroidism |

| Unexplained weight loss | Can indicate underlying disease or malignancy |

| Medication history | Intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUDs), anticoagulants, tamoxifen, hormonal therapies, herbal remedies (e.g. ginseng, soya, ginkgo) alter oestrogen levels or coagulation parameters and cause irregular menstruation |

| Related symptoms: sustained intermenstrual bleeding, pelvic pain | Pelvic pain or the presence of any pressure symptoms can be indicative of uterine cavity abnormality, histological abnormality, adenomyosis or fibroids |

| Personal/family history of a coagulation disorder – easy bruising, bleeding gums, prolonged bleeding after minor injuries, epistaxis or HMB since onset of menstruation | Can be an indication of von Willebrand disease |

Physical examination

A physical examination should be performed by an appropriate healthcare professional when a patient presents with HMB accompanied by other related symptoms (e.g. pelvic pain) or when a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) is indicated for treatment (see Table 2)[2],[12]

.

| Physical examination | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Observed pallor | Pale skin, conjunctiva and nail beds may indicate anaemia |

| Pelvic (bimanual) exam | May reveal uterine fibroids, adnexal masses or pregnancy. A tender uterus may suggest fibroids, adenomyosis, endometritis or pregnancy. Fibroids and pregnancy can also present with an enlarged uterus |

| Speculum exam | Can reveal lesions that are a source of bleeding and will require a biopsy |

| Obesity, non-pitting oedema, hair loss and brittle nails | Can be signs of hypothyroidism |

| Obesity, hirsutism and acanthosis nigricans | May indicate polycystic ovary syndrome |

| Acne, male pattern hair loss, hirsutism and clitoromegaly | Can be symptoms of excessive androgens |

| Jaundice, hepatomegaly and ecchymosis | Symptoms of liver disease and altered coagulopathy |

| Enlarged thyroid | Indicative of hypothyroidism |

Diagnostic tests

A full blood count should always be performed[12]

. In addition, a thyroid-stimulating hormone test, serum-free testosterone and a prothrombin time/activated partial thromboplastin time test could be informative depending on the symptoms identified while history-taking or during the physical examination[2],[12]

. Testing for coagulation disorders (e.g. von Willebrand disease, or platelet disorders) may be indicated when patients have had HMB since the onset of their menstruation or if there is a family history of such disorders[12]

. Other diagnostic tests may also be required (see Table 3).

| Diagnostic test* | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Pelvic ultrasound | When larger fibroids are suspected (the uterus is palpable abdominally, and/or pelvic mass probable, and/or inconclusive examination because of obesity). This test can be offered as an alternative if a hysteroscopy has been declined |

| Hysteroscopy | If the patient history suggests submucosal fibroids, polyps or endometrial pathology (i.e. persistent intermenstrual/irregular bleeding, obesity with infrequent heavy bleeding, polycystic ovary syndrome, women on tamoxifen, or where previous treatment has failed) |

| Endometrial biopsy (at time of hysteroscopy) | Recommended for those at high risk of endometrial pathology |

| *Routine serum ferritin levels are not required for patients with standalone heavy menstrual bleeding nor are female hormones or thyroid hormones. | |

Management

Treatment for HMB should be offered when there is no other suspected pathology or when women are waiting for further investigations or definitive treatment (see Table 4)[13]

,[14]

.

| Treatment option | NICE-recommended line of treatment[13] ,[14] | Dose | Common adverse effects (AEs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) 52mg | 1st | Should be inserted within seven days of the onset of menstruation (remove after five years and replace if required) [15] | Depression, headache, nausea, irregular bleeding, abdominal pain, acne, alopecia, back pain, breast pain, expulsion, hirsutism, migraine, nervousness, pelvic pain, peripheral oedema, salpingitis[25] |

| Tranexamic acid 500mg (oral) | 2nd NB. For over-the-counter treatment, patients do not need to have received a prior treatment | 1g three times a day (tds) to four times daily (qds) at the onset of heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) for a maximum of four days[18],[26] | Diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting[27] |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) Mefenamic acid (oral) | 2nd | 500mg tds on the first day of HMB until symptoms have subsided[19],[20],[28] | Diarrhoea, rashes, stomatitis[28] |

| Combined oral contraceptives | 2nd | See individual product information. Three packets can be taken consecutively without pill-free weeks[9] | Mood changes, headaches, nausea, fluid retention, breast tenderness[13] |

| Norethisterone 5mg (oral) | 3rd | 5mg tds from days 5 to 26 of cycle[13] | Weight gain, bloating, breast tenderness, headaches, acne[13] |

| Injected progesterone 50mg/ml (intramuscularly) | 3rd | 5–10mg daily for 5–10 days until two days before onset of menstruation[29] ,[30] | Weight gain, irregular bleeding, amenorrhoea, premenstrual like syndrome[13] |

| GnRH analogue (subcutaneous, intramuscularly, intranasal) | Alternative option. Has been used in secondary care | See individual product information. Because of AEs, it should not be used for more than six months[14] | Menopausal-like symptoms[13] |

| Ulispristal acetate 5mg (oral) | N/A Under review by European Medicines Agency – no new treatment courses to be commenced[12] | 5mg daily during first week of menstruation for up to three months[23],[31] | Abdominal pain, back pain, diarrhoea, dizziness, fatigue, gastrointestinal disturbances, headache, menstrual irregularities, muscle spasms, nausea, vomiting[31] |

First-line treatment

According to NICE, the recommended first-line treatment is a LNG-IUS if long-term management (≥12 months) is expected[9],[13]

. A LNG-IUS (a progestogen) inhibits the endometrial synthesis of oestrogen, therefore preventing proliferation and, sometimes, ovulation[9],[15]

,[16]

. It may take at least six cycles to see the maximal benefits and, during this time, there can be changes in bleeding patterns that can last longer than six months[9],[12]

. After one year of use, a LNG-IUS has been shown to decrease menstrual blood loss by up to 96%[9],[13]

. It is not only cost effective, but is the option of choice when preservation of fertility is important[5]

.

Second-line treatment

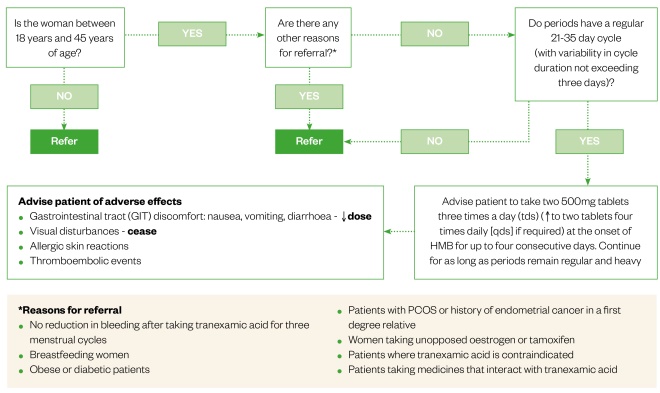

Recommended second-line treatment includes tranexamic acid, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and combined oral contraceptives (COCs)[12],[13]

.

Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic — a potent inhibitor of the activation of plasminogen to plasmin — which inhibits fibrinolysis, increases clot formation and reduces blood loss by up to 58%[13],[17]

,[18]

. Tranexamic acid tablets are available over the counter (OTC) as a pharmacy (P) medicine (see Figure 1). It should be noted that patients do not need to have been treated with a LNG-IUS (or any other treatment) before OTC tranexamic acid can be provided[17]

.

The anti-inflammatory activity of NSAIDs and their inhibitory actions on PGs reduces bleeding by 49%[13]

. NSAIDs would only be appropriate in an OTC setting if HMB occurred concurrently with dysmenorrhea because NSAIDs (apart from mefenamic acid, which is a prescription-only medicine) are not currently licenced for HMB in the UK. Therefore, the only suitable OTC treatment for HMB would be tranexamic acid[12],[19]

,[20]

.

COCs contain both oestrogen and progesterone, and have been estimated to reduce blood loss by up to 50%[9],[13]

. As COCs can also regulate bleeding, they have the additional benefit of reducing the number of menstruation cycles (three packets can be taken consecutively without pill-free weeks)[9]

. COCs are preferred when NSAIDs are inappropriate or contradindicated[14]

.

Figure 1: Supply of tranexamic acid over the counter (OTC)

Flowchart illustrating the criteria to be followed when supplying tranexamic acid tablets OTC

Third-line treatment

Norethisterone is the recommended third-line treatment. It prevents the proliferation of the endometrium and reduces blood loss by up to 83%[13]

. Injected progesterone can be an alternative to oral norethisterone[14]

.

In the event of initial treatment failure (i.e. no improvement after three menstrual cycles on tranexamic acid and/or NSAIDs), a combination of non-hormonal treatment and one hormonal treatment can be trialled prior to specialist referral[14]

. It is important to note that tranexamic acid should not be used in combination with COC or a LNG-IUS owing to an increased risk of venous thromboembolism[14],[21]

.

Alternative management options

In secondary care, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists have been used to stop the production of oestrogen and progesterone, thereby decreasing menstrual blood loss and resulting in amenorrhoea in 89% of women[13],[14]

. Owing to their AEs (e.g. osteoporosis, vasomotor symptoms) long-term use (>6 months) is not recommended. GnRH agonists are principally used pre-operatively to decrease peri-operative blood loss and to reduce uterine and fibroid size[14]

.

Surgical treatments (i.e. hysterectomy, endometrial ablation, myomectomy and uterine artery embolisation [UAE]) are also treatment options[14]

; however, hysterectomy and ablation can result in loss of fertility[12]

. There is currently no strong evidence to support fertility preservation following surgery with either myomectomy or UAE[22]

, but it has been suggested that myomectomy may increase pregnancy rates compared with UAE[14]

.

Ulipristal acetate is indicated for use in adult women of reproductive age for either peri-operative treatment of moderate-to-severe symptoms of uterine fibroids or for the intermittent treatment of moderate-to-severe symptoms of uterine fibroids[23]

. However, in February 2018, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) made a recommendation that no new patients should be started on ulipristal acetate owing to reports of hepatotoxicity, including hepatic failure resulting in liver transplantation[24]

. The Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) — a sub-committee of the EMA — has recommended monthly liver function tests (LFTs) for all patients currently on ulipristal acetate, with cessation of treatment if LFTs are twice the upper limit of normal[24]

. Patients are advised to repeat LFTs two to four weeks after treatment cessation[24]

, and to report any nausea, vomiting, upper abdominal pain, lack of appetite, tiredness or signs of jaundice. These are temporary measures until the pending conclusion of a review of ulipristal acetate by the EMA (start date of November 2017).

Fertility preservation

While hormonal treatments (LNG-IUS, COCs, norethisterone, injected progesterone and GnRH analogues) have contraceptive actions, they are reversible and therefore preserve fertility. Likewise, while NSAIDs and tranexamic acid are contraindicated in pregnancy and may affect fertility (e.g. mefenamic acid), the effects are reversible[19],[20]

. However, surgical intervention is often irreversible and should be avoided in patients where fertility preservation is important.

Quality of life

It is important for pharmacists and other healthcare professionals to be aware of cultural, social and educational backgrounds of patients that present with HMB to ensure that the best quality of care is offered and that informed decisions are always made.

One review found the health-related quality-of-life score for women with HMB was below the 25th percentile for the general female population because it causes absence from work and affects physical, emotional and social wellbeing[4]

.

In 2014, the RCOG National HMB Audit found that ethnicity-influenced treatments, outcomes and experience of care, where improvements in condition and surgery were less likely for those of a non-white ethnicity[4]

. Non-white women reported being less satisfied with both the information they received and the decision-making process[4]

. It has been suggested that these findings may be a result of cultural differences[4]

. While differences in treatment and outcomes have also been reported in women from less affluent backgrounds, the difference in their overall experience of care was relatively small[4]

.

Summary

A wide range of treatments (including OTC options) for HMB or menorrhagia is available in pharmacies. Community pharmacists, in particular, are able to help women manage this condition that can negatively impact quality of life. Effective history-taking is key for effective management, as is identification of patients requiring urgent referral. Women seeking advice from pharmacists about HMB should be given evidence-based information and be actively involved in treatment decisions, as outlined in this article.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

How to have effective consultations on contraception in pharmacy

What benefits do long-acting reversible contraceptives offer compared with other available methods?

Community pharmacists can use this summary of the available devices to address misconceptions & provide effective counselling.

Content supported by Bayer

References

[1] NHS Choices. Heavy periods. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/heavy-periods (accessed June 2018)

[2] Assessment of menorrhagia. BMJ Best Practice. Available at: http://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/171 (accessed June 2018)

[3] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heavy menstrual bleeding. Quality standard. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs47/resources/heavy-menstrual-bleeding-pdf-2098671748549 (accessed June 2018)

[4] Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. National heavy menstrual bleeding audit. Final report July 2014. Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/research–audit/national_hmb_audit_final_report_july_2014.pdf (accessed June 2018)

[5] Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Advice for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) services and commissioners. November 2014. Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/research–audit/advice-for-hmb-services-booklet.pdf (accessed June 2018)

[6] Maresh MJ, Metcalfe MA, McPherson K et al. The VALUE national hysterectomy study: description of the patients and their surgery. BJOG 2002;109:302–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01282.x

[7] Livingstone M & Fraser IS. Mechanisms of abnormal uterine bleeding. Hum Reprod Update 2002;8(1):60–67. PMID: 11866241

[8] Adelantado JM, Rees MC, Bernal AL et al. Increased uterine prostaglandin E receptors in menorrhagic women. BJOG 1998;95:162–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1988.tb06846.x

[9] Maybin JA & Critchley HOD. Medical management of heavy menstrual bleeding. Women’s Health 2016;12(1):27–34. doi: 10.2217/whe.15.100

[10] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion. Management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Reaffirmed 2017. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Management-of-Acute-Abnormal-Uterine-Bleeding-in-Nonpregnant-Reproductive-Aged-Women (accessed June 2018)

[11] Sweet MG, Schmidt-Dalton TA, Weiss PM et al. Evaluation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women. Am Fam Physician 2012;25(1):35–43. PMID: 22230306

[12] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management. NICE guideline [NG88]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88 (accessed June 2018)

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Bites. October 2011, No 35. Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/NICE_BitesOct2011.pdf (accessed June 2018)

[14] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Menorrhagia. CKS. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/menorrhagia#!scenario (accessed June 2018)

[15] Electronic Medicines Compendium. Mirena®. SmPC. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1132/smpc (accessed June 2018)

[16] Therapeutic Goods Administration Australia. Mirena®. Product Information. Available at: https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2009-PI-01235-3&d=2018040716114622483&d=2018042016114622483 (accessed June 2018)

[17] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Tranexamic acid P medicine. Quick reference guide. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/quick-reference-guides/tranexamic-acid-p-medicine#what (accessed June 2018)

[18] Electronic Medicines Compendium. Cyklo-f 500mg film coated tablets. SmPC. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9256/smpc (accessed June 2018)

[19] Electronic Medicines Compendium. Ponstan Capsules 250mg. SmPC. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1598/smpc (accessed June 2018)

[20] Electronic Medicines Compendium. Ponstan Forte Tablets 500mg. SmPC. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1732/smpc (accessed June 2018)

[21] Electronic Medicines Compendium. Tranexamic Acid 500mg Tablets. SmPC. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4489/smpc (accessed June 2018)

[22] Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Clinical recommendations on the use of uterine artery embolization (UAE) in the management of fibroids. Third edition 2013. Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/23-12-2013_rcog_rcr_uae.pdf (accessed June 2018)

[23] Electronic Medicines Compendium. Esmya 5mg Tablets (ulipristal acetate). SmPC. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3951 (accessed June 2018)

[24] European Medicines Agency. Women taking Esmya for uterine fibroids to have regular liver tests while EMA review is ongoing. News and press releases. 9 February 2018. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2018/02/news_detail_002902.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1 (accessed June 2018)

[25] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. British National Formulary. Levonorgestrel Monograph. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/levonorgestrel.html (accessed June 2018)

[26] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Medicines, Ethics and Practice. The professional guide for pharmacists. Edition 41. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/publications/medicines-ethics-and-practice-mep (accessed June 2018)

[27] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. British National Formulary. Tranexamic acid monograph. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/tranexamic-acid.html (accessed June 2018)

[28] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. British National Formulary. Mefenamic acid monograph. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/mefenamic-acid.html (accessed June 2018)

[29] Electronic Medicines Compendium. Gestone 50mg/ml. SmPC Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6574/smpc (accessed June 2018)

[30] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. British National Formulary. Progesterone monograph. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/progesterone.html (accessed June 2018)

[31] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. British National Formulary. Ulipristal monograph. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/ulipristal-acetate.html (accessed June 2018)