Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the diagnostic criteria for hypertension and blood pressure (BP) targets;

- Know the most used medications to treat hypertension and their main contra-indications, adverse effects and monitoring requirements;

- Support patients to manage their hypertension, including measuring their BP at home;

- Consider the practical aspects when conducting remote consultations for hypertension.

Introduction

High systolic blood pressure (BP) is the most prevalent modifiable cardiovascular (CV) risk factor and a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for 10.8 million deaths in 2019[1]. Hypertension is a common condition within the UK; in 2017, it was suggested that 11.8 million adults had a diagnosis, which equates to one in four adults[2]. Lowering systolic BP by 20mmHg (or diastolic BP by 10mmHg) halves the risk of dying from stroke, ischaemic heart disease and other vascular causes[3]. Additional information can be found in ‘Assessment and prevention of cardiovascular disease’. The systolic pressure refers to the pressure the blood exerts on the walls of the arteries when the heart is pumping blood around the body; it is the higher of the two numbers. The diastolic pressure is the smaller of the two numbers and refers to the pressure in the patient’s arteries when the heart is relaxed. A normal BP is typically in the range of 90/60mmHg to 120/80mmHg[4]. Ensuring good control of BP in general practice, especially when using their prescribing qualification, is an excellent opportunity for pharmacists to improve patient care and save lives.

This article will provide an overview of the pharmacological management of hypertension and the role of the pharmacist prescriber in general practice. For information on the range of non-pharmacological interventions that can be adopted by patients, please see ‘Managing hypertension: the role of diet and exercise’.

Diagnosis

In most people, hypertension is asymptomatic, hence the importance of regular BP checks. Patients with an optimal BP <120/80mmHg should have their BP checked in clinic at least every five years; if their BP is in the range of 120–129/80–84mmHg it should be repeated at least every three years; for those with high-normal BP readings, i.e. 130–139/85–89mmHg, their BP should be checked at least annually. This patient cohort may benefit from ambulatory blood pressure (ABPM) monitoring to assess for masked hypertension (when clinic readings are lower than those measured at home). A clinic value of systolic BP >140mmHg or diastolic BP >90mmHg must be followed up with ABPM to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension[5]. If clinic BP is more than 180/120mmHg, it may require specialist same-day referral or immediate treatment with antihypertensives, rather than waiting for ABPM results[6]. For full details on diagnosing hypertension, please refer to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines[6].

Pharmacists may be involved in the fitting and interpretation of ABPM. This involves fitting the patient with a BP monitor and cuff that automatically inflates — for example, every half hour during the day and less often (e.g. every hour) at night. A mean daytime figure of ≥135/85mmHg confirms a diagnosis of hypertension. An average of at least 14 daytime measurements should be taken during the patient’s usual waking hours to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension[6].

NICE recommends home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) if ABPM is not tolerated[6]. HBPM is when the patient measures their own blood pressure, this can be carried out on a device supplied by the GP practice or on a patient’s own device, provided it is approved for use in the UK. Patients wishing to purchase their own monitor can be directed to the British Heart Foundation online shop[7]. ABPM has the advantage over HBPM in that more readings will be collected, and at random, so patients cannot decide when their readings are done (e.g. during times when they feel very relaxed)[2]. Having access to nocturnal BP readings also allows identification of patients whose BP does not decrease at night. During sleep, it is normal for both systolic and diastolic BP to fall by about 10–20% of the daytime values[8]. If BP does not fall by 10% or more at night, patients are termed ‘non-dippers’ and are at increased cardiovascular risk[8].

A patient undergoing HBPM should be advised:

- For each BP recording, two consecutive measurements should be taken, at least one minute apart and with the person seated;

- BP should be recorded twice daily, ideally in the morning and evening;

- BP recording should be continued for at least four days, but ideally for seven days[6].

The measurements taken on the first day should be discarded and the average value of all the remaining measurements should be used to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension[6].

If ABPM or HBPM reveals that the patient’s mean daytime systolic blood pressure is ≥135mmHg and/or mean daytime diastolic BP is ≥85mmHg, a diagnosis of hypertension is made. NICE also subclassifies the diagnosis, according to stage, as shown in Table 1[6]. This will not affect treatment choice, but later stages are likely to require more aggressive treatment to bring BP to target.

Pharmacists working in general practice can check that the following tests, which are recommended by NICE, have been completed when a patient is diagnosed with hypertension. These are conducted to detect target organ damage (e.g. left ventricular hypertrophy, renal disease, hypertensive retinopathy)[6].

- Blood tests: Plasma glycated haemoglobin (HbA1C), electrolytes, creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration (those with chronic kidney disease [CKD] should have their BP well controlled), liver function and lipids;

- CVD risk calculated: A pharmacist can estimate QRISK3 by using various risk factors that have been recorded within the patient’s clinical records (e.g. BP, lipids, age, smoking status, ethnicity, family history of ischaemic heart disease and the presence of other conditions that increase CVD risk, such as CKD, atrial fibrillation, diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis). Those with an estimated CVD risk of ≥10% should have a formal QRISK3 calculated and offered a statin (atorvastatin 20mg daily) if ≥10%[9];

- Urinalysis: Test for haematuria and proteinuria using a reagent stick. Send urine for albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) to detect elevations in albuminuria, which is an early indicator of renal damage. Reduction in microalbuminuria has been shown to delay the progression of diabetic and non-diabetic CKD[10];

- Fundoscopy: Examination of fundi may detect hypertensive retinopathy; however, if the patient attends an optometrist for regular eye checks, most optometrists perform retinal photography as part of the routine screening, making fundoscopy in these patients less clinically useful[6,11];

- 12-lead electrocardiogram: This is useful for detecting left ventricular hypertrophy, previous myocardiaI infarction or atrial fibrillation[5]. For more information on the basic principles of the electrocardiogram and how to recognise common abnormalities, see ‘Interpretation of electrocardiograms’.

Pharmacists should also ensure that a sitting and standing check of BP is completed in the following patients:

- Those with type 2 diabetes mellitus;

- Those with symptoms of postural hypotension (e.g. falls or postural dizziness);

- Those aged 80 years and over[6].

When to start treatment for hypertension

NICE guidelines provide clinicians with a useful decision aid to support discussions with patients regarding when is the most appropriate time to commence pharmacotherapy[6]. Decisions to commence pharmacotherapy must be patient-centred and aligned to the key principles of medicines optimisation[12]. All patients should be able to understand the risks and benefits associated with the treatment recommendations offered to them, allowing them to make an informed decision about ongoing management.

NICE recommends that pharmacotherapy is commenced in conjunction with lifestyle modification in all patients with persistent stage 2 hypertension (clinic blood pressure ≥160/100mmHg), irrespective of age; more information on the role of lifestyle modifications can be found here. It will be necessary to use and apply clinical judgment to treatment decisions in patients of any age with documented frailty. Documented discussions regarding the commencement of therapy should occur with patients in whom persistent stage one hypertension is noted, who have one or more of the following:

- Target organ damage;

- Established CVD;

- Renal disease;

- Diabetes;

- QRISK3 score of greater than 10%[6].

Treatment choice and stepwise approach

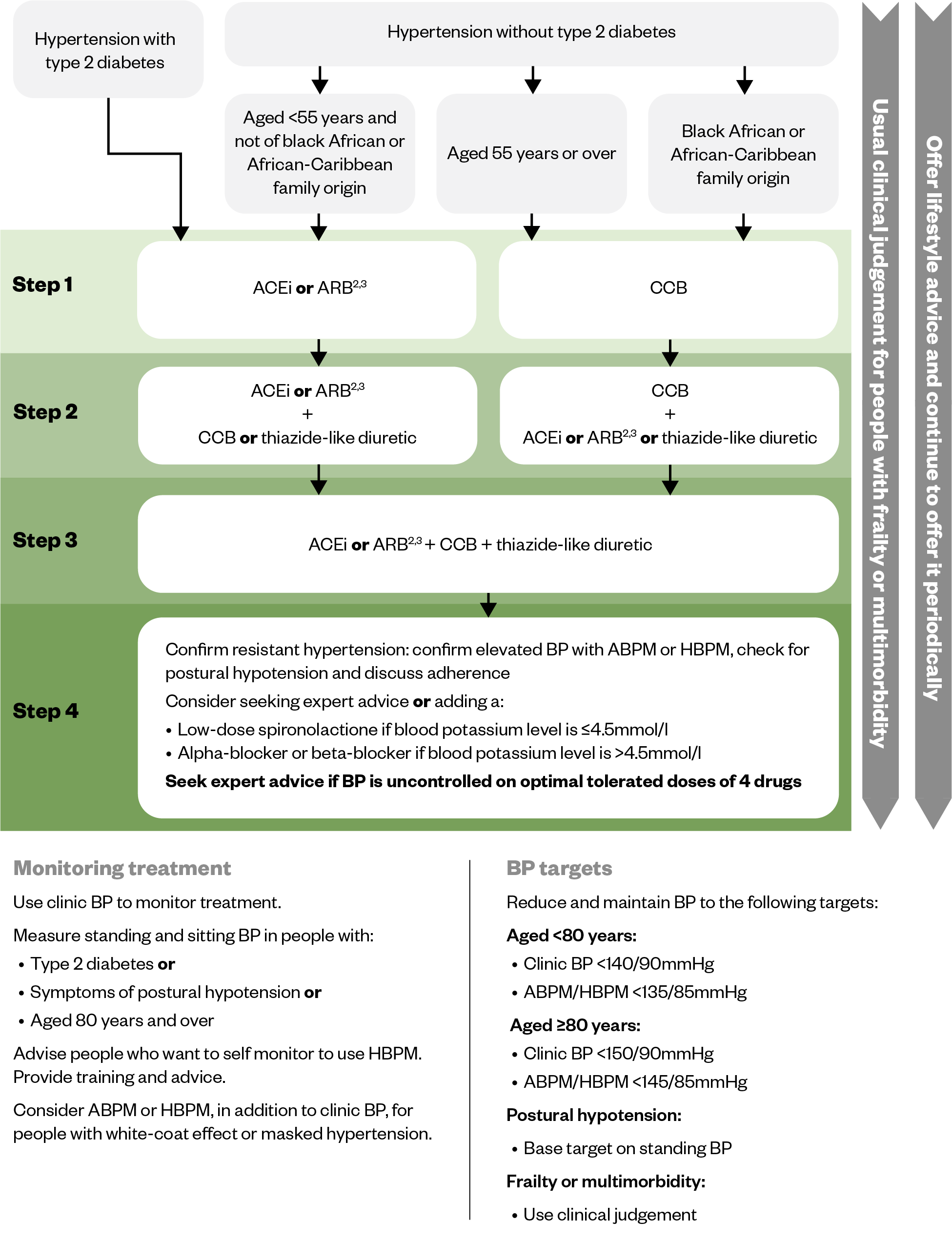

NICE guidelines take a stepwise approach to pharmacological management, with choices made that account for both the patient’s age and ethnicity[6]. This stepwise approach is outlined in Figure 1.

ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin receptor blockers; CCB: calcium channel blocker

Table 2 provides an overview of the medicine classes used in the management of hypertension as shown in steps one to three of the NICE algorithm[13–17] (see Figure 1). Note that treatment choice should be based on comorbidities and any contraindications or cautions relevant to the individual patient.

Please note, this article discusses some of the main points to consider when prescribing antihypertensive drugs. For full details on these medicines, consult the latest edition of the British National Formulary (BNF) or summary of product characteristics within the Electronic Medicines Compendium.

Management in specific patient groups

First-line choice of antihypertensive agent will depend on any patient comorbidities. For example, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are first-line choices for patients with diabetes and those with CKD, in whom good BP control is particularly important, owing to their increased CVD risk[6]. Note from Figure 1 that first-line treatment for patients who are of black African or African-Caribbean family ethnicity is a calcium channel blocker (CCB), irrespective of patient age[18]. This is owing to the influence of genetics — within this population, lower levels of renin result in a lesser response to medicines, which exert their pharmacological influence on BP through the renin-angiotensin system, such as in the use of ACEIs, ARBs and betablockers. If further treatment is required in this patient group, an ARB is preferable over an ACEI[6]. The choice of first-line antihypertensive agent will also be influenced by any compelling indications or contra-indications that an individual patient may have. For example, in patients with peripheral oedema or heart failure, or at risk of developing heart failure, a thiazide (or thiazide-like) diuretic is preferred to a CCB. Beta-blockers and ACEIs/ARBs may be first-line agents in patients who also have heart failure or in those who have had a myocardial infarction[19,20].

Considerations for treatment intensification

Only about a quarter of all patients with hypertension will be well controlled on monotherapy[21]. Many patients are likely to require two or more antihypertensive drugs to reach target. It is often beneficial to advise patients of this from the outset of treatment to avoid them feeling demotivated if control is not achieved with the first medication[22]. Please refer to the BNF for initiation and maintenance doses of antihypertensive agents[23]. The current thiazide-like diuretic of choice is indapamide, but it is important to note that for patients established on and stable with bendroflumethiazide 2.5mg once daily, there is no need to change therapy. There is also no additional anti-hypertensive benefit derived from bendroflumethiazide 5mg once daily; increasing to this dose predisposes the patient to an increased risk of side effects. Although the BNF states the dose range for lisinopril is 10mg to 80mg daily, there is little further antihypertensive benefit from increasing beyond 20mg daily[24].

It should be noted that the adverse effects of dihydropyridine CCBs are dose related, with a much higher rate of ankle swelling on amlodipine 10mg than amlodipine 5mg[25].

These factors need to be considered when deciding whether to increase the antihypertensive dose or add in an additional antihypertensive agent. In practice, combining two or more drugs allows lower doses to be used, which is likely to be better tolerated than titrating one antihypertensive drug up to maximum dose[26].

Blood pressure targets

Once established on therapy, patients must be aware of their own BP target. These targets should be based on the recommendations within NICE guidelines, while also considering patients’ underlying comorbidities, age and frailty status (these are summarised in Tables 3 and 4)[6]. The general target for patients aged under 80 years (including those with diabetes) is clinic BP <140/90mmHg for both primary and secondary prevention. For those aged 80 years or more, this target is <150/90mmHg. Note that some populations have lower targets than this; for example, those with CKD and proteinuria (ACR >70 mg/mmol), clinic BP target is <130/90mmHg[6]. Clinic BP should be used to monitor the response to treatment or lifestyle modifications. ABPM/HBPM can be used if clinic BP remains high following treatment or if ‘white coat’ hypertension (i.e. when BP readings are higher in clinical settings than when at home) is suspected. When the patient has achieved their target BP, they should be reviewed, no less frequently than annually.

Supporting patients to measure blood pressure at home and manage their hypertension

NHS England supports patients who wish to monitor their condition at home through the ‘bloodpressure@home’ scheme[7]. This scheme emphasises the importance of using a validated BP monitor and has involved the distribution of more than 220,000 BP monitors (since October 2020) around England, so that patients can record their BP and send their readings to their GP practice to review. The British Heart Foundation has a useful resource for patients on measuring BP at home, including where to buy validated monitors, how to measure BP, and lifestyle measures to reduce CVD risk[27]. Additional resources for both healthcare professionals and patients on home BP monitoring can be accessed on the British and Irish Hypertension Society’s website[28].

Impact of COVID-19 and remote monitoring

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in an unprecedented suspension to normal pathways of care. Dale et al. noted a decreasing trend in CVD medicines dispensed over the course of 2020/2021, suggesting a reduction in the active management of CVD in the UK population[29]. An estimated 491,306 fewer individuals commenced antihypertensive medication across England, Scotland and Wales during this time frame. The consequences of this are potentially huge, with an estimated additional 13,662 additional CVD events over the course of a person’s lifespan, should individuals remain untreated for hypertension. Detection and treatment levels are improving, but to date are not yet back to pre-pandemic levels[29].

During the pandemic, face-to-face appointments were quickly replaced with a ‘new normal’ of remote consultations either via the telephone or through video consultations, with both clinicians and patients having to adapt to this new approach[30]. Remote consulting has been part of the pharmacists’ skillset for many years, with advantages noted for patients and clinicians. Many consultations do not require a face-to-face appointment and conducting consultations remotely can be more convenient and time-efficient for both patients and healthcare professionals. When conducting hypertension reviews virtually, pharmacists should adopt the CONSULT checklist, which embodies the importance of a person-centred approach and shared decision making[31]. It is essential that the pharmacist conducting the remote consultation acknowledges that this may not be the best approach for all patients. Judgements must be made about the digital health literacy of the patient, their ability to use the digital platform and the capability of the patient to monitor their condition safely at home. Practices should ideally have clinically-validated BP monitors to loan to patients to aid in the accurate home monitoring of BP if ABPM monitoring is not suitable for them to assist with diagnosis.

Conclusion

Given the vast body of evidence supporting the benefits of antihypertensive treatment, pharmacist prescribers are in an excellent position to use their knowledge and skills around medicines to reduce morbidity and improve patient care. A summary box of the main counselling points to support patients with hypertension is given below.

Box: Summary

Patient counselling and support

- Patients should be educated on the consequences of untreated hypertension (e.g. increased risk of heart failure, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, peripheral artery disease, vascular dementia, retinopathy);

- Ensure patients understand the lifestyle modifications (dietary and exercise) they can undertake to reduce their blood pressure (BP) and generally improve their overall health;

- Patients should ‘know their numbers’ i.e. their latest BP reading and what their BP target is based on their age and underlying comorbidities;

- Counsel patients on the dose, frequency and anticipated adverse effects of their prescribed medications and the importance of adherence. Counselling should cover any pertinent points related to their medicines, such as the best time of day to take them and any important food/drink interactions;

- Ensure patients are aware of any signs and symptoms that warrant return to the prescriber for review (e.g. dizziness or severe ankle swelling);

- Advise patients on the frequency of intended monitoring to ensure hypertension is controlled to target and they are not experiencing unwanted adverse effects;

- Advise patients on the benefits of home monitoring, and the importance of measuring BP properly, using a validated BP monitor;

- Consider providing written patient information and refer patients to the NHS and British Heart foundation resources[7,27].

Points to consider when prescribing for hypertensive patients

- If involved in the diagnosis of hypertension, ensure all patients have had the recommended baseline monitoring and tests done;

- Provide appropriate lifestyle advice and encourage even small positive changes to diet and exercise;

- Before choosing an antihypertensive agent for a patient, carefully consider its contraindications, compelling indications and expected adverse effects;

- Prescribe medicines that have a good evidence base for hypertension. These tend to be the medicines listed in local formularies;

- Prescribe antihypertensives that can be taken once daily, where possible;

- Ensure that doses are appropriate for the patient’s level of renal function;

- Ensure that medicines have had sufficient time to achieve their antihypertensive effect before increasing the dose or adding another antihypertensive. Most medicines need at least four weeks to exert their effect;

- Consider the patient’s eligibility for a statin i.e. all secondary prevention patients and any primary prevention patients whose CVD risk is ≥10% over the next ten years (using QRISK3);

- Ensure that systems are in place to facilitate regular review of patients and that they are called for BP checks and the required blood monitoring tests at the appropriate time;

- Support patients as per summary above on counselling and support.

Disclosures

Neither author has any affiliation or financial involvement with any drug industries who produce antihypertensive medications. Briegeen Girvin has written review articles and research articles on hypertension previously, including for Prescriber journal.

- This article was amended on 10 January 2024 to correct an error in Figure 1

- 1Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2020;396:1223–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30752-2

- 2Hypertension: How common is it? National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hypertension/background-information/prevalence/ (accessed December 2023)

- 3Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. The Lancet. 2002;360:1903–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8

- 4High blood pressure. British Heart Foundation. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/risk-factors/high-blood-pressure (accessed December 2023)

- 5Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. European Heart Journal. 2018;39:3021–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339

- 6Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136 (accessed December 2023)

- 7Home blood pressure monitoring. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/cvd/home-blood-pressure-monitoring (accessed December 2023)

- 8Mahabala C, Kamath P, Bhaskaran U, et al. Antihypertensive therapy: nocturnal dippers and nondippers. Do we treat them differently? VHRM. 2013;125. https://doi.org/10.2147/vhrm.s33515

- 9Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181 (accessed December 2023)

- 10Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood-pressure-lowering treatment on outcome incidence. 12. Effects in individuals with high-normal and normal blood pressure. Journal of Hypertension. 2017;35:2150–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/hjh.0000000000001547

- 11How your eyes could help diagnose high blood pressure. University of Hertfordshire. 2022. https://www.herts.ac.uk/about-us/news-and-events/news/2022/how-your-eyes-could-help-diagnose-high-blood-pressure (accessed December 2023)

- 12Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 (accessed December 2023)

- 13Treatment summaries: Antihypertensive drugs. BNF. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/antihypertensive-drugs/ (accessed December 2023)

- 14Treatment summaries: Calcium treatment blockers. BNF. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/calcium-channel-blockers/ (accessed December 2023)

- 15Suggestions for Drug Monitoring in Adults in Primary Care. Specialist Pharmacy Service. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/home/tools/drug-monitoring (accessed December 2023)

- 16Staessen JA, Thijs L, Fagard RH, et al. Calcium Channel Blockade and Cardiovascular Prognosis in the European Trial on Isolated Systolic Hypertension. Hypertension. 1998;32:410–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.32.3.410

- 17Treatment summaries: Hypertension. BNF. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/hypertension/ (accessed December 2023)

- 18Lip GY. Hypertension and ethnicity – a perspective An article from the e-journal of the ESC Council for Cardiology Practice. European Society of Cardiology. 2004. https://www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-3/Hypertension-and-ethnicity-a-perspective-Title-Hypertension-and-ethnicity (accessed December 2023)

- 19Health Topics – Heart Failure. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/heart-failure-chronic/ (accessed December 2023)

- 20Health Topics MI-Secondary prevention. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/mi-secondary-prevention/ (accessed December 2023)

- 21Gradman A. Drug combinations. Hypertension Primer: The Essentials of High Blood Pressure: Basic Science, Population Science, and Clinical Management. Lippincott Williams & Williams 2003:408–11. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/ovid/hypertension-primer-the-essentials-of-high-blood-pressure-basic-science-population-science-and-clinical-management-4196 (accessed December 2023)

- 22High blood pressure – hypertension. NHS. 2023. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/high-blood-pressure-hypertension/treatment (accessed December 2023)

- 23British National Formulary. British National Formulary. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/ (accessed December 2023)

- 24Heran BS, Wong MM, Heran IK, et al. Blood pressure lowering efficacy of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003823.pub2

- 25Andrésdóttir MB, van Hamersvelt HW, van Helden MJ, et al. Ankle Edema Formation during Treatment with the Calcium Channel Blockers Lacidipine and Amlodipine: A Single-centre Study. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2000;35:S25–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005344-200000001-00005

- 26Johnston G. Fundamentals of cardiovascular pharmacology. Wiley-Blackwell 1999.

- 27How to choose a blood pressure monitor and measure your blood pressure at home. British Heart Foundation. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/heart-matters-magazine/medical/tests/blood-pressure-measuring-at-home (accessed December 2023)

- 28Home Blood Pressure Measurement. British Hypertension Society. https://bihsoc.org/resources/bp-measurement/hbpm/ (accessed December 2023)

- 29Dale CE, Takhar R, Carragher R, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cardiovascular disease prevention and management. Nat Med. 2023;29:219–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02158-7

- 30Nozato Y, Yamamoto K, Rakugi H. Hypertension management before and under the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons and future directions. Hypertens Res. 2023;46:1471–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-023-01253-7

- 31Remote consultations: how pharmacy teams can practise them successfully. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2020.20208102

2 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You might also be interested in…

Pharmacists can provide drug treatment for hypertension, WHO guideline says

Reducing systolic blood pressure to below NICE target could cut heart attacks and CVD deaths, study concludes

Please check in “Treatment choice and stepwise approach” section:

Under BP targets for Aged >= 80years, the article states Clinic BP < 50/90 mm Hg.

This should read < 150/90.

Hi Gillian,

Thank you for raising this. We have amended the figure.

Best wishes,

Sophie, senior subeditor