Shutterstock.com

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Understand the causes of hypothyroidism depending on their different aetiologies;

- Recognise the symptoms of hypothyroidism and understand the different biochemical tests that are used to diagnose the condition;

- Know how hypothyroidism is treated, including how the condition is monitored and how any side effects are managed.

Hypothyroidism occurs when the thyroid is unable to produce sufficient levels of thyroid hormone, owing to thyroidal dysfunction, insufficient stimulation or, in rare cases, where peripheral tissues are resistant[1]. Globally, it is most prevalent in countries where iodine deficiency is common because of low dietary intake, but this is difficult to accurately quantify owing to the differences among aetiological variations[1]. In countries such as the UK, where dietary iodine intake is usually sufficient, hypothyroidism affects around 1–2% of the population and is 10 times more common in women than men[1,2]. Incidence rises with advancing age, to more than 5% in patients aged over 60 years and more than 10% in patients aged over 80 years[3].

Thyroid structure and function

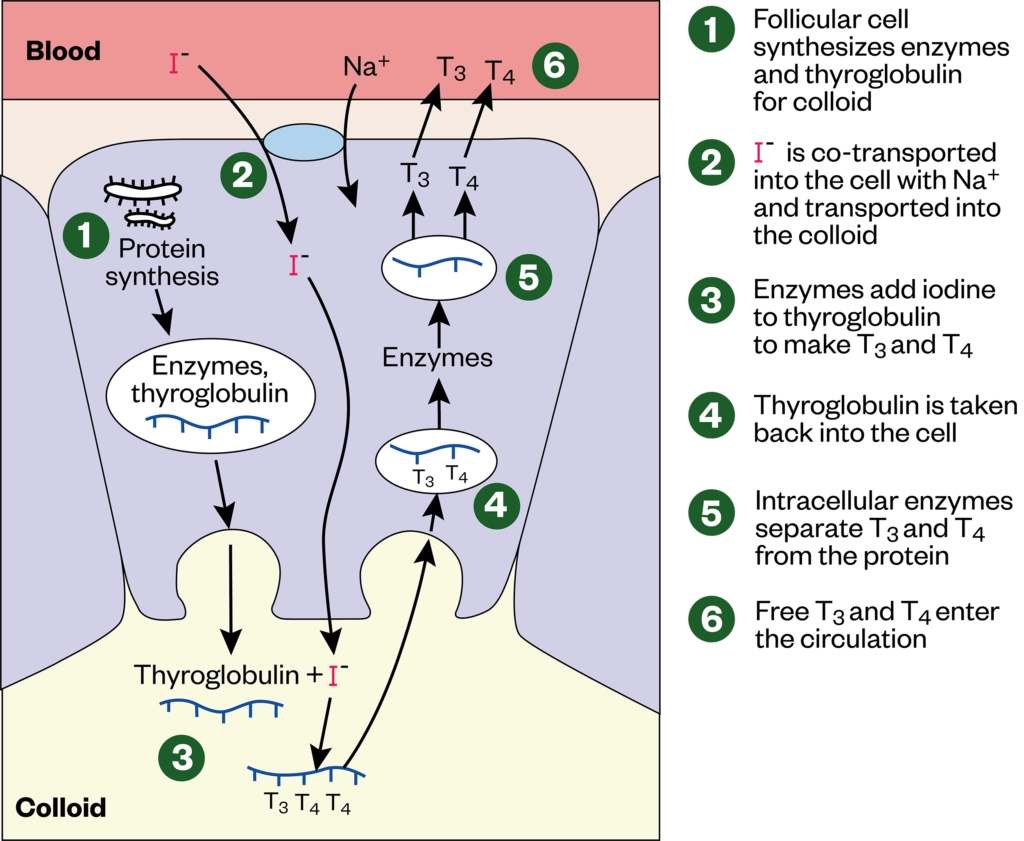

The thyroid is a small butterfly-shaped gland located at the front base of the neck[4]. It consists of two lobes that are connected by a thin tissue, known as the isthmus, and are comprised of cells called ‘thyroid follicles’[4]. The primary function of the thyroid is the synthesis and release of two main thyroid hormones — triiodothyronine (T3) and the relatively inactive prohormone tetraiodothyronine (T4), which is more commonly known as thyroxine[1]. T3 and T4 synthesis is summarised in the Figure.

T3 and T4 secretion is regulated by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which, in turn, is regulated by thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH), produced by the anterior pituitary gland and the hypothalamus, respectively[5]. In times of increased metabolic rate or when circulating levels of T3 and T4 are low, TRH and TSH stimulate the release of T3 and T4 into the bloodstream[4]. Around 80% of this will be T4 and only 10% will be the active T3, as T3 has a short half-life of 24–36 hours, in comparison to that of T4, which has a half-life of 6–7 days[1].

Causes

There are multiple types of hypothyroidism classified according to aetiology: primary, secondary, tertiary and peripheral.

The most common form is primary hypothyroidism, arising from dysfunction within the thyroid itself and accounting for around 99% of cases — of which 95% can be attributed to chronic autoimmune destruction of thyroid follicle cells, known as Hashimoto’s disease[1,6]. Other causes of primary hypothyroidism include dietary iodine deficiency — following ablative treatment for hyperthyroidism (i.e. total thyroidectomy) — or an adverse drug reaction (e.g. to amiodarone used to treat arrhythmias, or lithium used in the management of bipolar disorder)[5]. This can be further subcategorised into ‘overt’, where TSH is raised and free levels are low, or ‘subclinical’, where TSH is raised, yet free within standard reference range[5,7].

Both secondary and tertiary hypothyroidism — also referred to as central hypothyroidism — occur subsequent to reduced thyroid stimulation, owing to dysfunction outside the thyroid, either within the anterior pituitary gland or the hypothalamus, respectively; unlike primary hypothyroidism, these occur equally in men and women[6,8]. Central hypothyroidism most commonly arises from pituitary dysfunction, with 50% of cases attributable to pituitary adenoma, but can be caused by hypothalamic tumours, some infiltrative disorders (e.g. amyloidosis), following physical trauma, surgery or even medications (e.g. cocaine, glucocorticosteroids and metformin)[9,10]. Regardless, the decreased TSH and/or TRH production ultimately leads to decreased synthesis and release of thyroid hormones and hypothyroidism[5].

Finally, peripheral hypothyroidism occurs when freely circulating levels of T3, T4 and, often, TSH are sufficient. Symptoms of hypothyroidism occur despite patients’ normal biochemical results, either owing to thyroid hormone resistance arising from genetic disorders within peripheral tissues or thyroid hormone deactivation by increased production of ‘deiodinase 3’ produced by some tumour cells. These symptoms vary between patients and likely depend on the origin of the tumour[6].

Additionally, around 1 in every 2,000–3,000 babies born in the UK suffer from congenital hypothyroidism, where the thyroid gland is absent, underdeveloped or unable to synthesise thyroid hormones, yet there is no known direct cause[11].

Signs and symptoms

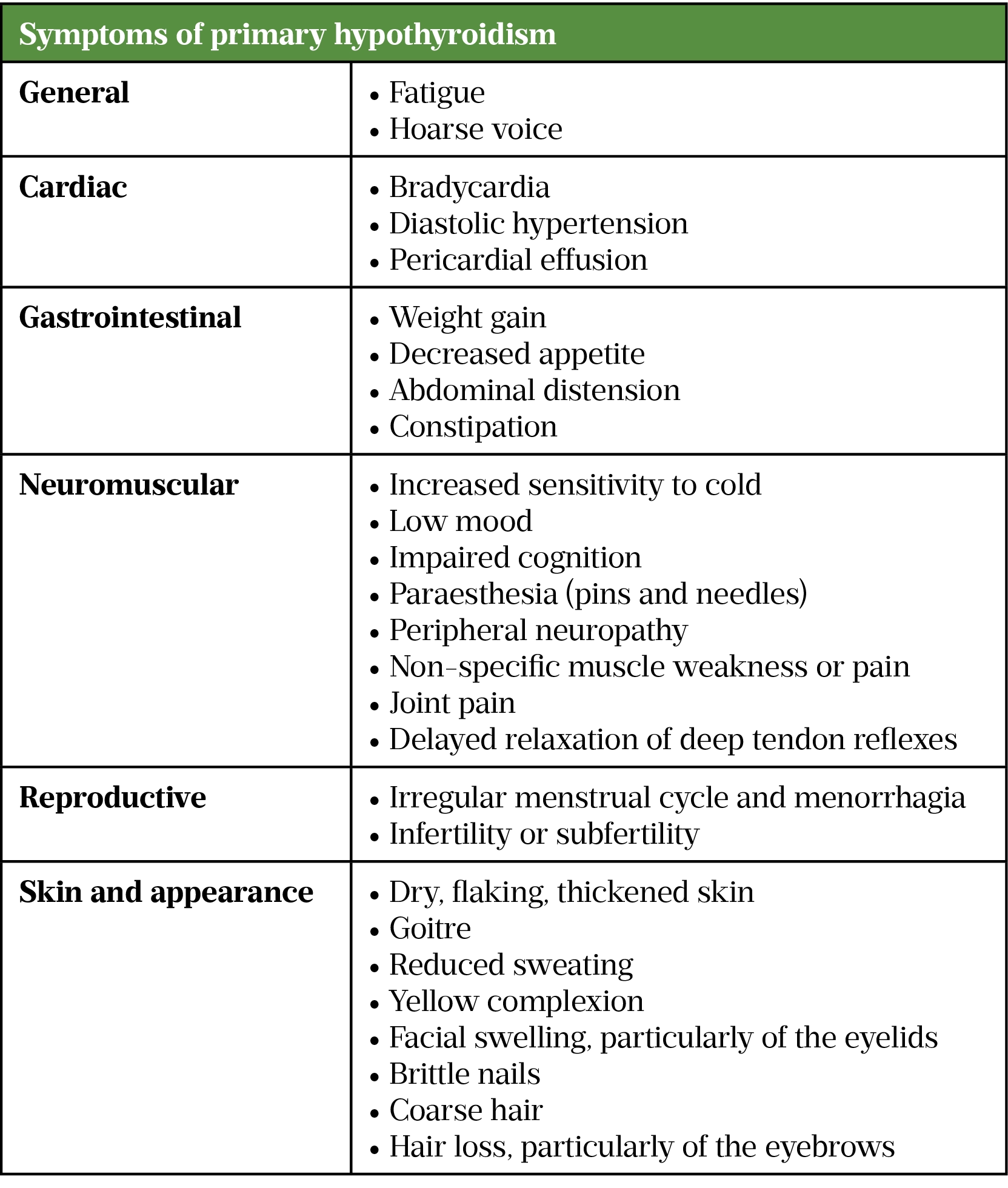

The symptoms of hypothyroidism are non-specific and, because of the insidious nature of the onset of the disease, are often missed during patient reviews or attributed to advancing age. Common symptoms of hypothyroidism are summarised in the Table[1].

Patients with central hypothyroidism are likely to have similar symptoms to those with primary hypothyroidism. However, they may also experience additional features, including general symptoms (e.g. recurrent headache), diplopia (i.e. double vision) and other visual disturbances[5]. More specific symptoms of pituitary dysfunction include erectile dysfunction, amenorrhoea, Cushing’s syndrome or acromegaly[5].

There are very few identifying symptoms for congenital hypothyroidism. Some babies struggle to sleep and feed, but this is not uncommon in newborns. All babies are therefore screened with a heel-prick test at five days of age for a number of conditions, including hypothyroidism[11].

Diagnosis

As symptoms of hypothyroidism are similar to ageing and menopause — as well as conditions such as anaemia, diabetes mellitus, Addison’s disease, vitamin deficiencies, stress and depression — it is important the thyroid is not forgotten during clinical examination and consultations[1,5,12].

Diagnosis of hypothyroidism is based on patients’ presenting symptoms, alongside biochemical testing of TSH and free T4 levels (FT4)[7,13]. Testing of the ‘free’ hormone ideally provides a more reliable diagnostic result, as it only represents hormone available for action, as opposed to inactive protein-bound hormone[1,14].

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance recommends that all patients presenting with new-onset atrial fibrillation, type 1 diabetes or other autoimmune disorders should be offered biochemical testing for thyroid dysfunction and that it should be considered in patients with unexplained depression and anxiety[13].

Initial testing of TSH level alone, if within reference range of 0.4–4mU/L, is sufficient evidence to rule out primary hypothyroidism[13]. If TSH is raised, a free T4 level, ideally tested from the same sample, is performed to confirm primary aetiology[12]. A high TSH and low FT4 would indicate appropriate hypothalamic-pituitary response to low hormone levels and the thyroid gland’s inability to respond to this adequate stimulation. However, if TSH is low, both a free T3 (FT3) and FT4 level should be ordered, ideally from the same sample, to investigate for secondary hypothyroidism and also rule out potential hyperthyroidism[13]. FT3 is regularly within range even in severe hypothyroidism and is therefore not considered diagnostically relevant for hypothyroidism[12]. Reference ranges for FT4 and FT3 are 9–25 pmol/L and 3.5–7.8pmol/L, respectively[15].

For patients who develop new symptoms or whose symptoms worsen, these tests should be re-checked no sooner than six weeks following initial testing, as re-testing any sooner is unlikely to show clinically significant changes[13]. Although NICE guidance suggests a TSH level should only be taken initially for people not thought to be suffering from central hypothyroidism, this can sometimes lead to a delayed diagnosis, especially in primary care[13]. Therefore, in clinical practice, many centres will test TSH and FT4 at presentation of symptoms as standard assessment[1].

Treatment

The aim of treatment is to effectively replace thyroid hormones through pharmacological intervention, to resolve symptoms and bring TSH levels back within standard range[1].

First-line treatment for primary and central hypothyroidism in all adults and children is oral levothyroxine, a synthetic form of T4, which provides replacement hormone to correct the deficiency in production[13]. Starting dose in people aged under 65 years with no pre-existing cardiovascular disease (CVD) is 1.6 micrograms/kg daily, rounded to the nearest 25 micrograms[13,16]. However, as overtreatment with levothyroxine can increase cardiac workload, people aged over 65 years or with pre-existing CVD should start at 25-50 micrograms daily, which can then be titrated up slowly every 4 weeks in steps of 25 micrograms until therapeutic effect is achieved[13]. For congenital hypothyroidism, starting doses of levothyroxine are given at 10–15 micrograms/kg per day for the first 3 months of life, after which the dose is adjusted dependent on TSH and free T4 levels[13].

Levothyroxine is contraindicated in individuals with hyperthyroidism, those who have experienced hypersensitivity reactions and in patients with uncontrolled adrenal insufficiency[17]. Patients with adrenal insufficiency should be started and stabilised on corticosteroid therapy prior to commencing levothyroxine to reduce the precipitating adrenal crisis on levothyroxine initiation[18].

For those truly intolerant of levothyroxine, liothyronine is a synthetic form of T3 that displays a similar pharmacological action[19]. Liothyronine is five times more potent, with a more rapid onset of action metabolism[20]. While there has previously been debate regarding the use of liothyronine as monotherapy for management of hypothyroidism, or even combination treatment with levothyroxine, the Royal College of Physicians strictly advises against this, owing to a lack of clinical evidence[5,11,21]. Although there is a small cohort of patients who require liothyronine, because of this lack of clinical evidence and greater cost, specialist endocrinologist assessment and consultation is vital for use within hypothyroidism management[20,22].

Pharmacists experienced with thyroid disorders may provide direct patient care through provision of thyroid clinics in primary or secondary care, assessing and managing patients as part of their multidisciplinary teams.

Monitoring

Although treatment is the same, monitoring of primary and central hyperthyroidism differ. For patients with primary hypothyroidism, regular blood monitoring of TSH levels is required to ensure patients are optimised on the most appropriate dose of levothyroxine. This should take place 4–6 weeks after starting treatment, and be repeated every 3 months until levels stabilise[13,16]. If a patient’s dose is too high, this will suppress TSH production, resulting in a low TSH level. Conversely, if a dose is too low, this will not adequately correct TSH values and will be indicated by a high TSH level. A patient would be considered as stabilised on a dose once two consecutive TSH levels are reported within standard range, which can take up to six months[13]. Once achieved, monitoring should be conducted annually, at a minimum, with additional TSH monitoring needed following any dose change to assess if further titrations are required[13]. For patients with central hyperthyroidism, TSH levels fail to provide an accurate overview of treatment response, as the nature of dysfunction impairs the homeostatic feedback loop that would otherwise correct TSH levels in response to adequate FT4[6]. Therefore, in practice patients with central hypothyroidism are monitored and dose adjusted on FT4 alone[1,14].

Prescribing of levothyroxine is usually generic so patients may often be switched between brands, dependent on stock at the community pharmacy they visit[23]. There are multiple reports of patients experiencing adverse effects — often symptoms of hypo- or hyperthyroidism — in response to switching between brands of levothyroxine, although the cause of this remains unclear[7,23]. In response to these reports, a 2021 Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency alert advises healthcare professionals to check thyroid function tests in those presenting with these symptoms and to ensure continuity of brand for these patients through product-specific prescribing[23]. If patients continue to experience poor thyroid control despite adhering to a specific brand, an oral solution formulation may be offered as an alternative[23].

Side effects

Levothyroxine is generally well tolerated, but may have some mild and inconvenient side effects, such as flushing, restlessness, palpitations or excessive sweating[17]. If persistent, these symptoms may be a sign that patients’ FT4 is raised owing to an unrecognised interaction increasing absorption (such as taking with grapefruit), or that their levothyroxine dose is too high and they should be signposted for review[24]. Although uncommon, severe side effects of insomnia, onset of angina or even thyrotoxic crisis can occur[17]. While angina can often be managed by withholding levothyroxine for 1–2 days and recommencing at a lower dose, mortality associated with thyrotoxic crisis is high (around 10–20%), and therefore requires immediate medical attention[25].

Medications counselling

Community pharmacists are often the last healthcare professional (HCP) a patient will see before commencing new treatments, and are likely the only HCP that patients see face to face for repeat supplies. They are therefore ideally placed to provide counselling on potential adverse effects to support patients’ adherence while on treatment[26].

Treatment of hypothyroidism often requires lifelong levothyroxine therapy, so patients may struggle with adherence, and even appropriately counselled patients may lack the capacity or capability to take their medication correctly[1]. In these cases, levothyroxine can be given in once-weekly doses with assistance from a relative or community team; this has been shown to be safe and effective[1].

It is imperative to discuss drug interactions during medications counselling. Absorption of levothyroxine can be reduced by ferrous sulphate, calcium supplements and cholestyramine[15,27]. As a prohormone, levothyroxine is hepatically metabolised to active T3. Therefore, drugs that affect liver enzymes, such as phenytoin, carbamazepine and rifampicin, may also impact therapeutic levels[16,17].

Food intake can reduce absorption of levothyroxine by up to 80%[28]. Traditionally, patients have been counselled to take levothyroxine upon waking, 30 minutes before breakfast. However, studies have shown that taking levothyroxine in the evening or just prior to sleep provides similar biochemical thyroid function test corrections[28]. The best advice for patients is to take this medication on an empty stomach at a time that best fits their lifestyle, as long as they do so daily[29].

Complications

Pregnancy

Insufficient T4 can cause impaired fertility and harm the foetus during pregnancy, leading to miscarriage in some cases[30,31]. Any patient who has, or has previously suffered with, thyroid disease and is planning a pregnancy will need to consult with their GP and have frequent TSH level monitoring[5]. The British Thyroid Foundation recommend that once aware of the pregnancy, patients should increase their levothyroxine dose by 25–50 micrograms immediately and arrange for a TSH level to be taken[30]. TSH levels should be monitored every 4–6 weeks during the pregnancy, with the aim of achieving a TSH level of <2.5mU/L in the first trimester and <3.0mU/L in the second and third trimesters[31]. Patients’ TSH level will need to be checked again a few weeks after birth; most patients are able to return to their previous optimal dose[31]. Patients wishing to breastfeed should be supported in doing so and should be informed that levothyroxine is safe to be taken when breastfeeding[16,32].

Myxoedema coma

Patients with severe hypothyroidism may present in myxoedema coma, a rare complication affecting an estimated 0.22 patients per 1 million each year in the Western world; around 40% of whom are unaware of their thyroid dysfunction prior to admission[1,33]. Characterised by reduced consciousness, hypothermia, macroglossia, periorbital oedema and coarse hair, this severity of hypothyroidism is often fatal with high mortality rates of 25–60%[33,34]. Initial treatment includes intravenous levothyroxine and, in more severe cases, liothyronine[34]. Intravenous hydrocortisone is also given until adrenal insufficiency is ruled out, as levothyroxine therapy would further exacerbate an Addisonian crisis[18,34]. Once controlled, patients can be switched to oral levothyroxine and maintained as per standard hypothyroidism management[33].

This article has been reviewed by the expert author to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in The Pharmaceutical Journal in June 2021.

- 1Kalhan A, Page M. Thyroid and parathyroid disorders. In: Whittlesea C, Hodson K, eds. Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. London: : Churchill Livingstone 2018. 744–761.

- 2Vanderpump MPJ. The epidemiology of thyroid disease. British Medical Bulletin 2011;99:39–51. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldr030

- 3Ingoe L, Phipps N, Armstrong G, et al. Prevalence of treated hypothyroidism in the community: Analysis from general practices in North-East England with implications for the United Kingdom. Clin Endocrinol 2017;87:860–4. doi:10.1111/cen.13440

- 4Betts G, Young K, Wise J, et al. The Endocrine System: The Thyroid Gland. In: Anatomy and Physiology. Houston, Texas, USA: : Rice University 2017. N/A.https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology

- 5Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Hypothyroidism. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2020.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hypothyroidism/ (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 6Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, et al. Hypothyroidism. The Lancet 2017;390:1550–62. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30703-1

- 7Okosieme O, Gilbert J, Abraham P, et al. Management of primary hypothyroidism: statement by the British Thyroid Association Executive Committee. Clin Endocrinol 2015;84:799–808. doi:10.1111/cen.12824

- 8Persani L. Central Hypothyroidism: Pathogenic, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Challenges. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2012;97:3068–78. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-1616

- 9Haugen BR. Drugs that suppress TSH or cause central hypothyroidism. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2009;23:793–800. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2009.08.003

- 10Persani L, Brabant G, Dattani M, et al. 2018 European Thyroid Association (ETA) Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Central Hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J 2018;7:225–37. doi:10.1159/000491388

- 11Congenital Hypothyroidism. British Thyroid Foundation. 2018.https://www.btf-thyroid.org/congenital-hypothyroidism (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 12Vaidya B, Pearce SHS. Management of hypothyroidism in adults. BMJ 2008;337:a801–a801. doi:10.1136/bmj.a801

- 13Thyroid disease: assessment and management: NICE guideline [NG145]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng145 (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 14UK guidelines for the use of thyroid function tests. British Thyroid Association, The Association for Clinical Biochemistry and British Thyroid Foundation. 2006.https://www.british-thyroid-association.org/sandbox/bta2016/uk_guidelines_for_the_use_of_thyroid_function_tests.pdf (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 15Thyroid Function Tests. British Thyroid Foundation. 2018.https://www.btf-thyroid.org/thyroid-function-tests (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 16British National Formulary: Levothyroxine (online) . Joint Formulary Committee. 2021.https://www.medicinescomplete.com (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 17Levothyroxine Tablets BP 100 microgram Summary of Product Characteristics. Accord UK LTD. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5806/smpc (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 18Murray JS, Jayarajasingh R, Perros P. Lesson of the week: Deterioration of symptoms after start of thyroid hormone replacement. BMJ 2001;323:332–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7308.332

- 19Liothyronine Sodium BP 20microgram Tablets Summary of Product Characteristics. Advanz Pharma. 2019.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5905/smpc (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 20Guidance – prescribing of Liothyronine. NHS England. 2019.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/RMOC-Liothyronine-guidance-V2.6-final-1.pdf (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 21The diagnosis and management of primary hypothyroidism. Royal College of Physicians. 2011.https://static1.squarespace.com/static/53b1670ee4b0be242b013ed7/t/543ee743e4b05588d7c67389/1413408579862/RCP+Diagnosis+and+management+of+primary+hypothyroidism+2011.pdf (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 22British National Formulary: Liothyronine (online). Joint Formulary Committee. 2021.https://www.medicinescomplete.com (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 23Levothyroxine: new prescribing advice for patients who experience symptoms on switching between different levothyroxine products. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency . 2021.www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/levothyroxine-new-prescribing-advice-for-patients-who-experience-symptoms-on-switching-between-different-levothyroxine-products (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 24Your guide to hypothyroidism. British Thyroid Foundation. 2018.https://www.btf-thyroid.org/hypothyroidism-leaflet (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 25Carroll R, Matfin G. Review: Endocrine and metabolic emergencies: thyroid storm. Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology 2010;1:139–45. doi:10.1177/2042018810382481

- 26How pharmacists can encourage patient adherence to medicines. The Pharmaceutical Journal Published Online First: 2018. doi:10.1211/pj.2018.20205153

- 27Thyroid dysfunction and drug interactions. The Pharmaceutical Journal Published Online First: 2015. doi:10.1211/pj.2015.20068601

- 28Bach-Huynh T-G, Nayak B, Loh J, et al. Timing of Levothyroxine Administration Affects Serum Thyrotropin Concentration. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2009;94:3905–12. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-0860

- 29Vanderpump M. What time should I take my levothyroxine? An endocrinologist’s blog for patients. 2020.https://www.markvanderpump.co.uk/blog/posts/what-time-should-i-take-my-levothyroxine (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 30Thyroid disorders and pregnancy. British Thyroid Foundation. 2019.https://www.btf-thyroid.org/thyroid-disorders-and-pregnancy (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 31De Groot L, Abalovich M, Alexander EK, et al. Management of Thyroid Dysfunction during Pregnancy and Postpartum: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2012;97:2543–65. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-2803

- 32Thyroid. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). 2018.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501739/ (accessed 1 Jun 2021).

- 33Mathew V, Misgar RA, Ghosh S, et al. Myxedema Coma: A New Look into an Old Crisis. Journal of Thyroid Research 2011;2011:1–7. doi:10.4061/2011/493462

- 34Gish DS, Loynd RT, Melnick S, et al. Myxoedema coma: a forgotten presentation of extreme hypothyroidism. BMJ Case Reports 2016;:bcr2016216225. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-216225