Shutterstock.com

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Know the different pharmacological options available for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, and understand how management differs between the conditions;

- Understand management strategies for different patient groups, including pregnant and breastfeeding women;

- Understand the screening requirements prior to treatment initiation and the need for any ongoing monitoring;

- Provide vaccination advice, where appropriate.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a term used to describe Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). This article is the second in a series and focuses on the management of IBD. Information relating to symptoms and diagnosis can be found in the first part ‘Inflammatory bowel disease: symptoms and diagnosis’.

The primary aims of IBD management is to induce and maintain remission, reduce the risk of complications and improve patient quality of life (QoL)[1]. Remission can be determined as either clinical or endoscopic[1]. There is currently no consensus on how clinical and endoscopic remission are defined, additional evidence is required for how they can be used in clinical practice as outlined by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines[1].

Patients are generally managed by a gastroenterologist in conjunction with IBD specialist nurses, as well as pharmacists and colleagues in primary care. Other specialties, such as radiology, surgery, psychology, dietetics and metabolic bone disease, may be involved as needed. Particularly complex cases are usually managed by tertiary centres.

The impact of COVID-19 has significantly affected the diagnosis and management of IBD. Face-to-face clinics have largely been replaced by remote consultations (via telephone or video call), with reduced capacity for endoscopic investigations and elective surgeries. This has resulted in increased waitinmg times for patients requiring investigation of their symptoms, as well as delays for patients with IBD who are waiting for outpatient review appointments. Many of these patients are prescribed immunosuppressant medications that place them at higher risk of complications. The long-term impact of these changes remains to be seen[2].

This article will cover current pharmacological management strategies for both UC and CD.

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians have an important role to play in the management of IBD as part of a multidisciplinary team (MDT). Currently, only 13% of IBD teams in the UK meet the standards for pharmacist involvement, demonstrating that additional work is needed in this area[3]. This includes recognising signs of a flare-up and facilitating appropriate referral to primary or secondary care services for review; being aware of the local IBD specialist team and their contact details to aid referral or request advice; developing or being familiar with shared care policies between primary and secondary care for monitoring of drugs; managing home care services for supply of high-cost treatments and helping signpost patients to IBD support groups for information and advice.

Pharmacological management

Despite advancements in therapy over the past two decades, pharmacotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment with surgery reserved for refractory cases[1]. Surgical management is beyond the scope of this article; more information on this can be found in the BSG guidelines[1].

Conventional pharmacological therapy options include aminosalicylates, corticosteroids and thiopurines. These are usually initiated in secondary care following a formal diagnosis. After discharge home, primary care management with secondary care team input occurs via shared care agreements.

When consulting with patients, healthcare professionals should consider the thoughts and feelings of patients when making decisions about therapy. The following questions can help to facilitate the discussion:

- How do you feel about your illness?

- What is important to you in terms of controlling symptoms and quality of life?

- What activities are important to you?

- What are the thoughts and experiences that take you away from parenteral products (i.e. products for injection or infusion)?

Pharmacists should ensure patients are counselled on the following points:

- Medications — especially administration of rectal (see Box 1) and subcutaneous (SC) formulations to ensure effectiveness and adherence.

- Adherence to therapy even during periods of disease remission. For example:

- “It is important to continue to take your medications even when your symptoms are under control. This helps reduce the risk of complications, such as flares or colorectal cancer developing.”

- Importance of smoking cessation. For example:

- “Have you thought about trying to quit smoking? It is one of the best things you can do to help your IBD symptoms. I am here to help you quit. Let me know if you would like more information.”[1]

All information and advice provided to patients and/or carers with IBD should be appropriate for their age and cognitive level.

Aminosalicylates

The 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) class of drugs (mesalazine and sulphasalazine) are considered safe and effective long-term treatment options for IBD, and are available in both oral and rectal preparations (suppositories, enemas and foams)[1,4].

The mechanism of action of 5-ASAs is not well understood; however, they are thought to reduce inflammation by inhibiting release of interleukin-1 and preventing recruitment of leucocytes into the bowel wall[5].

Common adverse effects include renal complications, drug-induced liver injury, dyspepsia, rash, urticaria and eosinophilia[6,7]. When starting patients on therapy, it is important that baseline and ongoing renal and liver function tests are taken because renal disease or liver disease may be a primary complication of IBD itself[1].

In mild-to-moderate UC, 5-ASAs are the treatment of choice and all patients should be offered a 5-ASA at a dose of 2.0-3.0g/day orally. Patients experiencing flare-ups can be escalated to 4.0–4.8 g/day[1]. Ideally, all UC patients should be offered a combination of oral and enema 5-ASA[1]. The 5-ASA used will depend on the location and disease type. Pharmacists can optimise medication regimens to help reduce waste; for example, recommending once daily 5-ASA dosing instead of twice daily.

Studies have shown that a combination of high-dose oral and rectal mesalazine therapy is more effective at inducing remission of mild-to-moderate symptoms compared with oral therapy alone. Time to remission is also quicker (between two to eight weeks for most patients)[8–15]. This is particularly true for patients also taking steroids[8].

Once in remission, 5-ASA therapy for UC should be reduced to a maintenance dose as appropriate, to limit adverse effects but still reduce the risk and frequency of flares[16].

Patients on oral monotherapy who experience incomplete response should have a rectal agent added[17,18].

Treatment with 5-ASAs is not recommended for induction or maintenance treatment of CD[19–21]. This is despite a few historic studies showing possible benefits of sulphasalazine when used to induce remission[22,23].

However, mesalazine suppositories are the first-line therapy for proctitis, a disease confined to the rectum that is common in people with UC and CD[24]. It achieves a much higher drug concentration in the mucosa with a more rapid onset of action and better efficacy than oral 5-ASA monotherapy or rectal steroids alone[25]. Combination therapy with oral and rectal 5-ASAs achieve higher response rates and should therefore be offered first line to both UC and CD patients with proctitis; however, in mild cases a topical preparation may suffice[1].

Despite the efficacy of 5-ASAs, it remains practically difficult for some patients to administer and retain rectal formulations. Pharmacists should provide support and education around administration as summarised in Box 1.

Box 1: Practical consultation tips for administration of rectal formulations

Example advice given to patients for administration of suppositories:

- You might find it easier to use a suppository before bed to minimise any leakage;

- Wet the tip of the suppository with water or a water-based lubricant to make it easier to insert;

- Try not to go to the toilet for an hour after inserting the suppository to give it time to work;

- You may experience leakage during the night. This is normal because the suppository starts to melt once inserted. Placing a towel on the bed may help to absorb any leaks;

- If a suppository comes out within ten minutes of inserting it, do not worry. Try another suppository.

Example advice given to patients for administration of enemas and foam enemas:

- You might find it easier to use enemas before bed to minimise leakage;

- When administering the enema, stand with one leg raised on a chair or lie down on your side. This gently creates an opening for the enema applicator which can then be inserted into the bottom as far as possible;

- If lying on your side, a pillow may help to lift the bottom up. You may also use a towel to absorb any leakage.

For sleeping, find a comfortable position that helps keep the liquid inside for as long as possible. The longer it stays in, the better chance it will work.

Cessation of 5-ASA’s in patients with UC and Crohn’s colitis should only be considered once the risks and benefits have been considered. There is some evidence that 5-ASAs may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer in these patients; however, it is unclear whether this a direct effect of 5-ASAs or owing to benefits related to mucosal healing[26].

Corticosteroids

Patients with UC and CD who do not achieve remission with 5-ASAs can be escalated to a more potent anti-inflammatory agent, such as corticosteroids; however, they should only be used acutely and not for maintenance therapy. The aim of treatment is to induce remission and to maximise local effects while limiting systemic effects. This has been even more important during the COVID-19 pandemic because it is vital to limit the time spent in hospital by immunocompromised patients[27].

Corticosteroids, such as prednisolone, beclomethasone and budesonide, are broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory agents that work by modulating several inflammatory pathways[28,29].

Prednisolone

Oral prednisolone is superior to 5-ASA for inducing remission of mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe UC[1,30]. It is also effective as an oral step-down agent for patients that have responded to the initial treatment of intravenous (IV) corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 100mg four times a day) following hospitalisation for acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC)[1,31]. Patients should be assessed for a clinical and biochemical response after three days of IV) steroid therapy to determine the need for salvage pharmacological or surgical therapy[31].

The optimal dose for both UC and CD is uncertain; however, the current dose recommendation for oral prednisolone is 40mg a day, with an aim to taper over six to eight weeks (usually tapered by 5mg per week)[1]. There is limited evidence with doses higher than 40–60mg/day; doses above this range are associated with increased adverse effects with repeated courses (e.g. acne, oedema, mood disturbance, infection risk, glucose intolerance, dyspepsia and osteoporosis)[32].

Second generation corticosteroids

Beclomethasone diproprionate and slow release budesonide are second generation corticosteroids with a high affinity for the intracellular glucocorticoid receptor in the GI tract, exerting local and selective, potent anti-inflammatory effects at the site of inflammation[33]. These drugs have a lower systemic availability owing to extensive pre-systemic metabolism within the mucosa of the small intestine and the liver and are therefore known as ‘topically acting’ even though they are taken orally[34].

The efficacy of these second generation corticosteroids is superior to placebo and mesalazine for mild-to-moderate UC; superior to placebo for ileo-colonic CD; and inferior to systemic glucocorticoids with an improved safety profile for both indications[1,24,35–37]. Once remission is achieved, these should be tapered over one to two weeks[1]. It is important to ensure they are prescribed with the brand specified as they have slightly different sites of release and licensed indications.

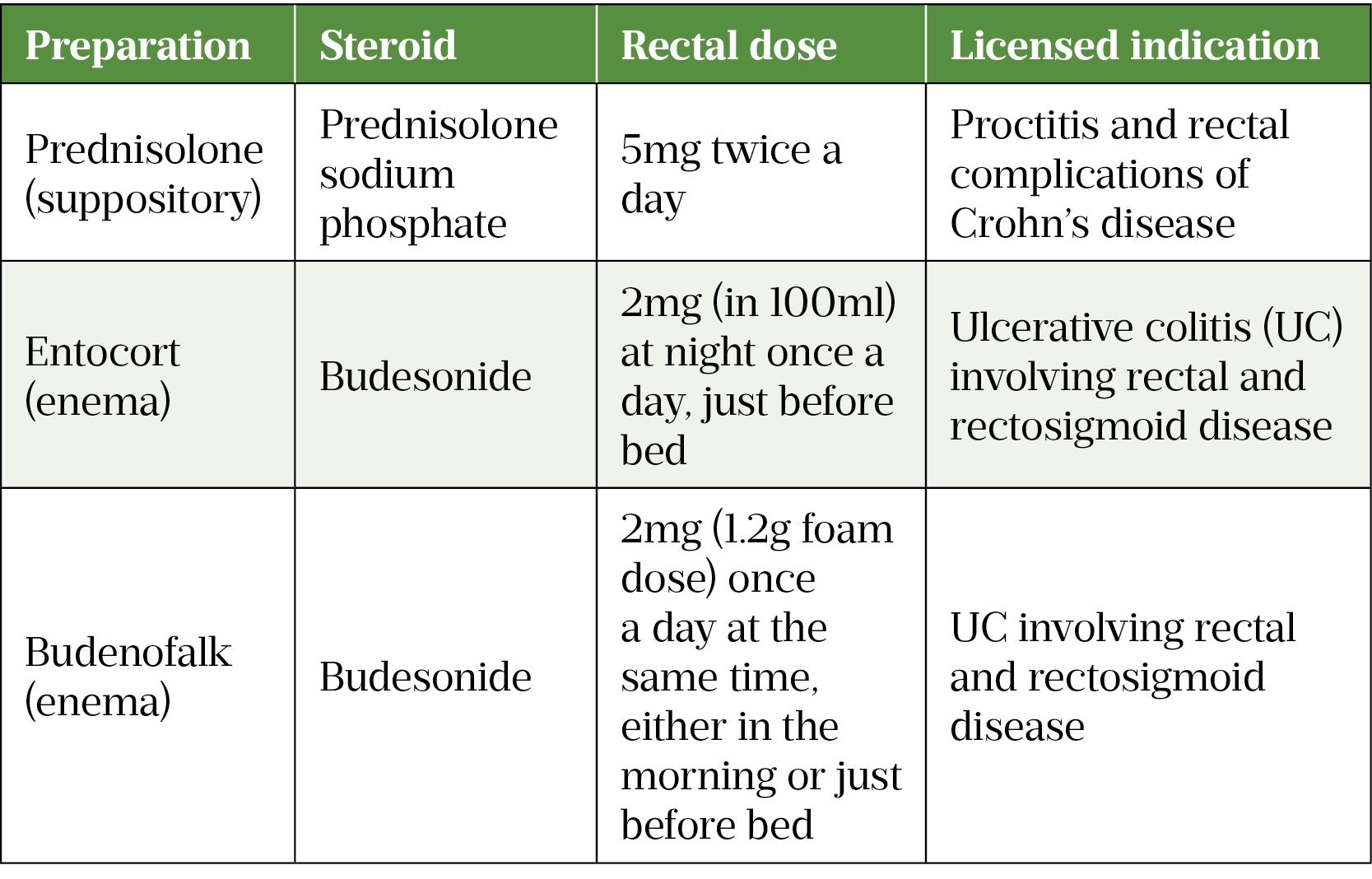

Rectal steroid preparations can be used to treat proctitis, proctosigmoiditis and colitis in CD. Rectal mesalazine should be used for UC owing to higher efficacy[24,35]. It is important to choose the preparations according to the part of the colon affected, see Table 1[38–40].

Immunomodulators

Drugs that alter the activity of the immune system are known as immunomodulators. In IBD therapy, these include thiopurines, methotrexate, ciclosporin and biologic or targeted cell therapies[41].

Use of these agents increases the risk of patients succumbing to opportunistic infections which are easily preventable through screening and vaccination[41]. Before initiating any form of immunosuppressant or biologic therapy, it is good practice to pre-screen patients with IBD for the following and receive the relevant vaccinations if necessary:

- Tuberculosis;

- Hepatitis B;

- Hepatitis C;

- Varicella-Zoster;

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV);

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV);

- Cytomegalovirus;

- Baseline renal function;

- Baseline liver function[1].

All patients with IBD receiving immunosuppressants should also receive influenza, pneumococcal and COVID-19 vaccinations (see below for more information).

Thiopurines

Around 60% of patients with IBD receive oral thiopurines (e.g. azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine or in rare cases tioguanine). These immunosuppressive agents deactivate T-lymphocyte processes that lead to inflammation and are effective at maintaining steroid-free remission in CD and UC[24,35,42]. However, they should not be used to induce remission[43–46].

In patients with UC, thiopurines can be initiated if ≥2 exacerbations have occurred within a 12-month window; if remission is not maintained by 5-ASAs or after a single episode of ASUC[24].

For patients with CD, thiopurines can be added to glucocorticoids or budesonide to induce remission if the patient has had ≥2 exacerbations within a 12-month period or if tapering of glucocorticoids has failed[35]. Monotherapy can be continued to maintain remission of CD[35].

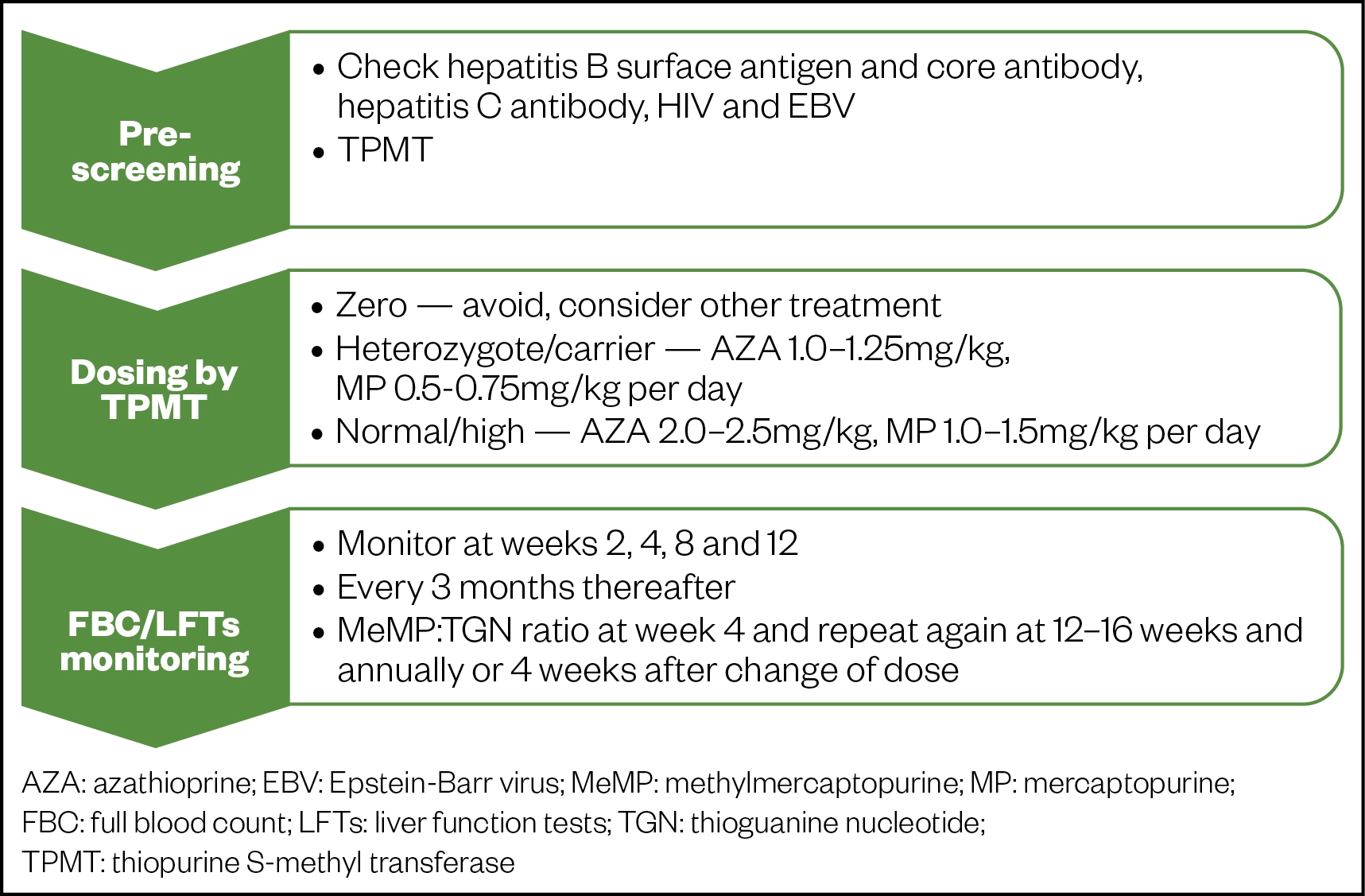

Prior to starting therapy, patients should undergo pre-screening for viral infections and enzyme activity that could affect dosing. Figure 1 summarises dosing and the necessary tests required.

Nausea may be experienced by a minority of patients, this can lead to intolerance[47]. Advising patients to take their tablets after meals can help to relieve this. Severe diarrhoea, recurring on rechallenge, has been reported in patients treated with azathioprine and pharmacists should be aware that such symptoms might be drug-related[47]. Other serious adverse events from thiopurine use include myelosuppression and opportunistic infections, deranged liver function and hypersensitivity reactions, including pancreatitis[48]. Long-term thiopurine use may be associated with an increased risk of lymphoproliferative disorders and non-melanoma skin cancer. The risk of relapse should be weighed against the risks of long-term thiopurine therapy. In particular, the risk of lymphoma rises markedly with increasing age[43,49,50]. At least two years should elapse between completion of cancer treatment and starting therapy for IBD with thiopurines or biologics, although this depends on the agent being considered and availability of other options to control disease[51].

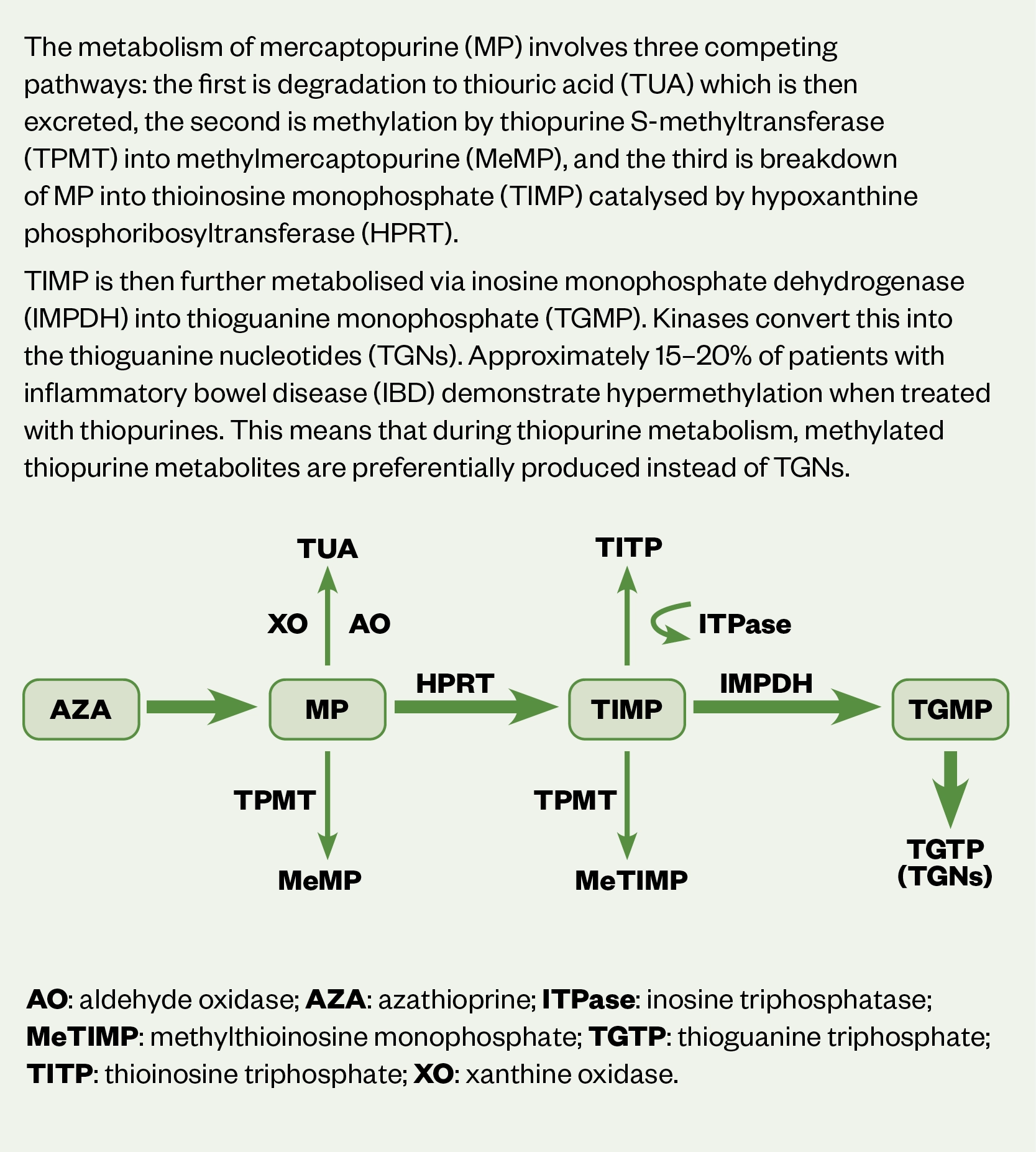

Thiopurines are associated with a high risk of toxicity and careful monitoring is advised[42]. Figure 2 provides a detailed summary of thiopurine metabolism. After administration, the pro-drug azathioprine is metabolised to 6-mercaptopurine (MP). Thioguanine nucleotide (TGN), the active metabolite of MP disrupts DNA replication of rapidly dividing cells, such as activated T-cell lymphocytes. Increased levels of TGN can lead to leucopenia and bone-marrow failure[42].

Conversion of MP to TGN occurs through several processes, including methylation by the enzyme, thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TMPT)[42]. Individual TMPT activity determines the extent of MP metabolism with increased risk of severe and potentially fatal myelosuppression at standard doses in patients who have no or low levels of activity[42]. It is therefore necessary to assess levels of TMPT prior to starting therapy[42].

Tests for TGN levels determine the thioguanine count in DNA structure and should ideally be requested at weeks 4 and 12 after starting therapy, thereafter bi-annually/annually, or 4 weeks after a dose change[42]. A therapeutic TGN range of 235–450 pmol/8 x 108 red blood cells (RBCs) correlates with a sufficient clinical response[52,53]. Increasing the dose by 25–50mg per day may be sufficient for TGN to reach therapeutic range, if subtherapeutic. Equally if levels are above range, reducing the dose by 25–50mg may be enough to bring it down to range[42]. See Figure 1 for further information on relevant dose adjustments[42].

Around 15–20% of patients with IBD demonstrate hypermethylation when treated with thiopurines, resulting in preferential metabolism of MP to methylmercaptopurine (MeMP)[54]. A ratio of MeMP to TGN of >11 is linked to poor response if levels of TGN are sub-therapeutic. In addition, MeMP levels >5,700 pmol/8 x 108 RBCs result in a higher risk of hepatoxicity[53]. Although monitoring of TGN:MeMP is routine in practice, wide variation in levels suggest poor cost-effectiveness[55].

In patients with sub-therapeutic TGN levels or associated hepatotoxicity, hypermethylation can be corrected using low-dose thiopurine (25–50% of standard monotherapy dose, i.e. 50–75% dose reduction of thiopurine in combination with allopurinol 100mg daily)[42]. The inhibition of xanthine oxidase blocks the conversion of MP into thiouric acid[56–58].

Emerging data suggest that thiopurine monotherapy and combination therapy with TNF antagonists may be associated with an increased risk of severe COVID-19. All risks and benefits for the use of thiopurines in the context of COVID-19 should be considered (e.g. age, disease severity, the risk of disease flare on withdrawal of thiopurine therapy and increased risk of immunogenicity). Further studies in large population-based cohorts are needed to confirm[59,60].

Other immunosuppressants

Use of immunosuppressants, such as methotrexate and ciclosporin, are rarely indicated following wider availability of biologics and targeted cell therapies. The introduction of biosimilars has also improved the cost-effectiveness of some biologic therapies[61]. Nevertheless, they are still useful as second-line agents to induce remission in CD when other agents, such as biologics fail[1].

The dose for methotrexate starts at 15mg weekly with SC formulations having better bioavailability compared with oral, particularly at higher doses, owing to malabsorption[1]. Folic acid (5mg weekly) should be given with methotrexate to reduce risk of gastrointestinal and liver toxicity[1].

Ciclosporin for ASUC treatment has been superseded by infliximab; however, IV ciclosporin can be given as salvage therapy for ASUC at 2mg/kg/day with a target trough concentration of 150–250ng/mL[1,62–64]. Therapeutic drug monitoring is required to minimise the risk of toxic side effects, including serious infections, nephrotoxicity, anaphylaxis and death[65,66]. Administration should be via non-PVC infusion sets to mitigate any adsorption of drug onto equipment[67].

Biologic and targeted cell therapy

Escalation to biologic or targeted cell therapy occurs when conventional options have failed or contraindications are present (e.g. hepatitis B infection, low levels of TPMT or severe renal/liver impairment). Initiation and management of therapy is overseen by secondary care clinicians[56].

Prior to initiation, it is important to consider the following:

- Mode of action;

- Practicality of administration for patient;

- Speed of onset, especially if the goal is to induce remission;

- Comorbidities (e.g. cancer, heart failure);

- Extraintestinal manifestations (e.g. uveitis, pyoderma gangrenosum);

- Supportive therapy[1].

Regional medicines optimisation committee (RMOC) guidance suggests that decisions regarding biologic treatments, whether in treatment naïve patients or in those using sequential therapies , should be based on shared-decision making to ensure treatment is appropriate, safe and clinically and cost effective[68]. It is therefore paramount that patients are offered the best choice of treatment first time in line with ‘get it right first time’ principles[69].

Anti-tumour necrosis factor monoclonal antibodies

Infliximab and adalimumab are licensed for both UC and CD with comparable efficacy, while golimumab is currently licensed for UC only[70–73]. These monoclonal antibodies bind and inactivate circulating tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, disrupting the inflammatory cascade with a more targeted approach than corticosteroids and thiopurines[71].

Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody with both murine and human amino-acid sequences and is available as IV and SC formulations[71]. IV infusions are administered at 5mg/kg at weeks 0, 2 and 6 reducing to every 8 weeks thereafter. Patients can be converted to 120mg SC every fortnight following IV loading at weeks 0 and 2[71]. Thiopurines can be added to avoid loss of response to infliximab providing an additive effect and thiopurine suppression of immunogenicity[74]. Monitoring of infliximab trough levels (target: 3–7 mg/mL) will determine whether dosing can be increased to 5mg/kg every 4 weeks or 10mg/kg every 8 weeks[75]. It is important that response is reviewed following the third dose post titration.

Adalimumab is a fully humanised monoclonal antibody available as a SC formulation. Licensed dosing is 80mg at week 0 then 40mg every fortnight thereafter. Clinicians can opt for an accelerated initiation with 160mg given at week 0, then 80mg at week 2, reducing to 40mg every fortnight thereafter[76–78]. Patients showing signs of losing response to therapy (e.g. signs of flare-ups) should have adalimumab levels measured (target: >8.5micrograms/mL) for consideration of dose escalation to 40mg weekly or 80mg every fortnight[79].

Combination anti-TNF-alpha and thiopurine therapy increases the risk of serious opportunistic infections and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. This should be weighed against the potential benefits[80,81]. Concomitant corticosteroids as a third immunosuppressive therapy when used to induce remission, may further increase the relative risk of serious and opportunistic infections. Prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jiroveci (previously carinii) with oral co-trimoxazole 960mg three times a week or 480mg daily should be considered[1,82].

There is an association between patients who carry the HLA-DQA1*05 gene and development of antibodies against anti-TNF agents[83]. Pre-treatment testing can determine which patients might benefit from combination anti-TNF-alpha and immunomodulator therapy[83,84].

Anti-integrin therapy

Movement of leucocytes into the intestinal mucosa facilitates the inflammatory response in IBD. Integrin are transmembrane receptors that facilitate cell adhesion. Inhibiting the actions of integrin on the surface of immune cells and endothelial cell adhesion molecules inhibits interaction between leucocytes and intestinal vasculature which blocks the inflammatory process[85].

Vedolizumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody that inhibits lymphocyte adhesion, particularly the mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1), which is selective for α4β7 integrin[86]. Vedolizumab is more specific to the GI tract than other leucocyte adhesion inhibitors, such as natalizumab, and has been shown to be both safe and effective in IBD[86–90].

Vedolizumab is licensed for both UC and CD for induction and maintenance therapy and is available as IV and SC formulations[86]. The licensed IV dosing is 300mg at weeks 0, 2 and 6, with 8 weekly infusions thereafter[86]. If the patient opts for the SC formulation as maintenance treatment, it must be initiated following at least two IV infusions (at weeks 0 and 2)[86]. The intravenous dose can be increased to 300mg every 4 weeks to target therapeutic levels >7.4micrograms/mL if patients are showing loss of response[91].

Vedolizumab is currently approved by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for moderate-to-severe active CD if anti-TNF treatment has failed, or if anti-TNF agents cannot be tolerated or are contraindicated[92]. For moderate-to-severe active UC, vedolizumab can be used as a first-line option[93].

Vedolizumab is associated with a theoretical risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML)[94]. Pharmacists should monitor for, and counsel patients on, any new or worsening neurological signs and symptoms, such as:

- Progressive weakness on one side of the body, or clumsiness of limbs;

- Disturbance of vision;

- Changes in thinking, memory and orientation, leading to confusion and personality changes[86].

Patients displaying any signs and symptoms suggestive of PML should be immediately referred to a neurology team and vedolizumab should be withheld[86].

Interleukin inhibitors

Ustekinumab is an antagonist of the p40 subunit of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-12 and interleukin-23, recently licensed for induction and maintenance therapy in CD and UC[95–97]. The initiation dose is always given intravenously at around 6mg/kg, thereafter it is switched to a SC formulation at 90mg 12-weekly or 8-weekly[95]. NICE currently recommends the use of ustekinumab for moderate-to-severe active CD for adults who have not responded to anti-TNF or conventional therapy or have contraindications to such therapies[98]. In moderate-to-severe active UC, ustekinumab is recommended in adults who have not responded or have contraindications to anti-TNF therapy[99].

Common side effects of ustekinumab include:

- Sore throat or cold;

- Dizziness and headaches;

- Diarrhoea, nausea or vomiting;

- Itching;

- Back pain, muscle pain or joint pain;

- Fatigue.

Patients should also be aware of less common side effects, such as depression, tooth infections, injection site reactions, Bell’s palsy and vaginal infections in women[100].

Janus kinase inhibitors

Small molecules called Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors disrupt phosphorylation of JAK enzymes on cytokine receptors, inhibiting inflammatory pathways in IBD[101].

Currently, tofacitinib is the only licensed JAK inhibitor for UC. It is formulated as an oral tablet and as a small molecule it does not have the issue of immunogenicity as with other immunomodulators[1]. It is dosed at 10mg twice a day for 8 weeks (this can be further extended for another 8 weeks for a total of 16 weeks if there is partial response), followed by 5mg twice a day for maintenance[102–104].

A recent network meta-analysis took into consideration all the available treatments for UC (except ustekinumab) and concluded that tofacitinib is an efficacious treatment for moderate-to-severe active UC and is likely to be a cost-effective use of NHS resources[105].

As a relatively new drug, tofacitinib carries a ‘black triangle’ warning, denoting that patients require extra monitoring while taking it[102]. Pharmacists must be aware of the contraindications, special warnings and precautions and ensure patients:

- Do not have risk factors for venous thromboembolism (see Box 2);

- Have a lymphocyte count >750 cells/mm3;

- Have a neutrophil count >2,000 cells/mm3, contraindicated if <1,000 cells/mm3;

- Have baseline lipid measurements;

- Are not at risk of serious infections;

- Have a full vaccination screening/history.

This list is not exhaustive, please refer to the summary of product characteristics for an extensive list[102].

Box 2: Venous thromboembolism risk with tofacitinib

Safety alerts were issues by the European Medicines Association in November 2019 and the Medicines Health products Regulatory Agency in March 2020 in light of an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) associated with the higher dosing of 10mg twice a day. It is important to exercise caution in the following[106]:

- Previous VTE;

- Patients undergoing major surgery;

- Immobilisation;

- Myocardial infarction (within previous three months);

- Heart failure;

- Use of combined hormonal contraceptives or hormone replacement;

- Inherited coagulation disorder;

- Malignancy[106,107].

Other VTE risk factors that should be considered include age, obesity (BMI >30), diabetes, hypertension and smoking status[106].

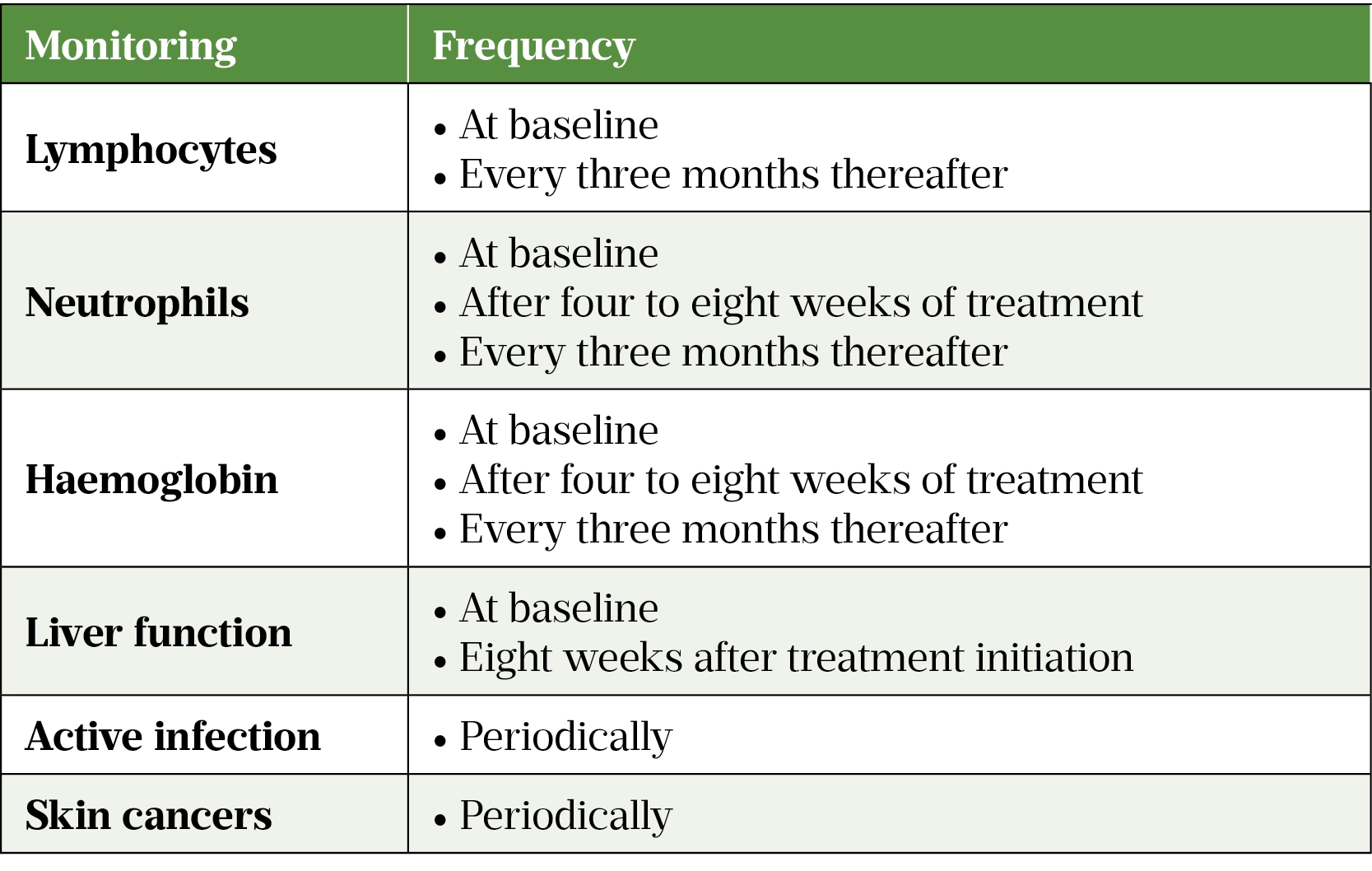

Additional monitoring for signs of infection, deranged liver function, skin cancer and cardiovascular events should be undertaken[108]. It may be practical to monitor all of these at baseline, at week eight and every three months thereafter, for the duration of treatment. Table 2 summarises the type and frequency of monitoring required.

The use of tofacitinib in patients with active infections is contraindicated. The benefits and risks must be considered in patients with recurrent infections, those who have a history of serious or opportunistic infection, or travel to areas of endemic mycoses, and in those who are immunosuppressed[106].

Ongoing monitoring

Nutrition is an important part of IBD because absorption and secretion of electrolytes is usually impaired, which can result in electrolyte and acid-base imbalances in IBD patients[109]. Electrolyte transport mainly takes place in the colon, therefore UC is typically associated with electrolyte disorders in contrast to CD[109]. These micronutrients play a vital role in regular cell function, energy production and immune function.

Nutritional assessment should be conducted by a dietician to identify appropriate management with patients at risk of malnutrition (undernourishment as well as overnourishment)[1,110]. Pharmacists should ensure important nutritional markers are monitored and corrected if required. The most common micronutrient deficiencies to be aware of are iron, calcium, selenium, zinc, magnesium, B12, folic acid, and fat-soluble vitamins, such as A, D, and K[111].

Vaccinations

Patients with IBD are at increased risk of opportunistic infections. It is therefore necessary that all immunosuppressed patients receive vaccination for influenza, pneumococcus and COVID-19.

The administration of live vaccines is contraindicated in patients on biologic agents and tofacitinib[71,72,86,95,102,112]. It is safe to administer a live vaccine four weeks prior to commencing biologic therapy[112]. Patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. anti-TNF, high dose corticosteroids, etc.) alone or in combination should avoid receiving live vaccines, until at least six months after terminating such treatment[112]. There is no contraindication for the administration of live vaccines to relatives or friends of patients on biologic or immunosuppressant drugs[112].

Influenza

Patients with IBD have a greater risk of contracting influenza and requiring admission to hospital[1]. Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all immunosuppressed patients, although vaccine efficacy may be reduced, particularly in those on anti-TNF therapy[1]. During biologic therapy, patients should receive seasonal inactivated influenza vaccines annually.

Pneumococcus

The pneumococcal vaccine should be given once only at two to four weeks prior to initiating a biologic as response after starting treatment can be poor[112]. If the patient is immunodeficient or presents with recurrent respiratory infections, titres may need to be measured[1,112].

COVID-19

The risks associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with IBD are very low and no one brand is better than the other. Neither IBD disease activity, nor the timing of SC/IV IBD medications, should delay vaccination. High-dose systemic corticosteroids, particularly in combination with other immunosuppressants, may reduce vaccine immunogenicity, as has been observed with annual influenza vaccination. Where possible, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination should be administered while patients are taking the lowest dose of systemic corticosteroid[113].

Vaccination of infants exposed to immunosuppressive drugs

Any infant who has been exposed to immunosuppressive treatment while in utero or via breastfeeding should have any live attenuated vaccination deferred[114]. As detectable levels of anti-TNF in the offspring are present in the first six months at least, the BSG guideline recommends live vaccines should be avoided in this period[1].

Current vaccination strategies with non-live vaccines for infants who have been exposed to a biologic medicine in utero do not differ from those for unexposed infants[112].

For up-to-date information, consult the Green Book[112].

Pregnancy & breastfeeding

Pregnancy

Patients planning to conceive should have their therapy optimised as best as possible to achieve remission. Additional emphasis should be given to general health to ensure adequate nutrition, smoking cessation and vaccination measures have been undertaken[1].

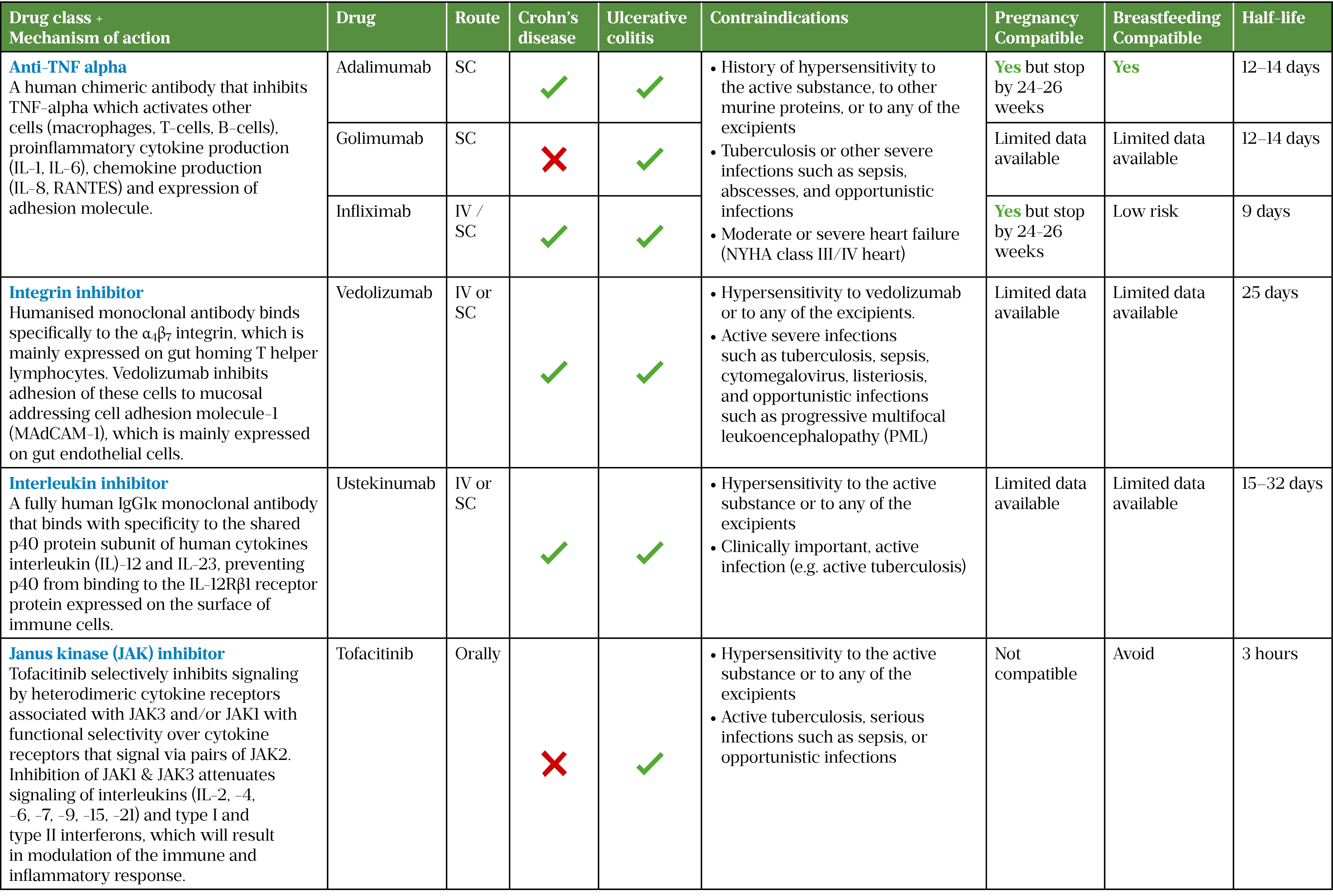

When giving family planning advice, clinicians (including pharmacists) should consider the half-life of the drug in use, advice on length of contraception after the most recent dose, as well as existing evidence for use in pregnancy and breastfeeding and paternal exposure if the drug is to be continued, see Table 3[1,115,116].

During pregnancy, patients require close surveillance by their consultants. Management should employ an MDT approach with obstetric input[1]. Most treatments, including VTE prophylaxis, are safe and the benefits outweigh the risks in pregnancy; however, avoiding methotrexate in patients of childbearing age is crucial owing to its major teratogenic effects[115]. Patients should be counselled about the risks to the foetus versus the benefits of continuing treatment throughout pregnancy[115].

In IBD, the physiological passage of immunoglobulins may have a deleterious effect upon the foetus with potential long-term implications (e.g. autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, myasthenia gravis, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, Sjogren’s syndrome)[116]. Infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab are all IgG1 monoclonal antibodies. For patients with active disease or a high risk of flare, therapy may be continued. However, for those with inactive disease it may be reasonable to stop at the start of the third trimester, in line with peak foetal development[1].

The decision to continue or stop biologic agents should be individualised, taking into account alternative therapies, the severity of the mother’s condition prior to therapy, the risk of disease flares caused by treatment cessation and the impact of a flare on the mother and the unborn child[1,116]. This should be discussed with the MDT. Delivery mode should be discussed with the obstetrician.

Breastfeeding

Breastfed infants of mothers receiving biologics, immunosuppressants or combination therapies have a similar risk of infection and development milestone at 12 months to non-breastfed infants and infants unexposed to these medicines[117].

A decision on whether to continue/discontinue breastfeeding or to continue/discontinue therapy should be made on an individual basis, taking into account the woman’s choice, the drug profile, the benefit of breastfeeding to the child, and the benefit of therapy to the woman[118].

For compatibility of the biologics and JAK inhibitors with breastfeeding, see Table 3[119–123].

Patient support

There are several organisations that patients can be signposted to:

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Shiva T Radhakrishnan, clinical research fellow (IBD), Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, for his support and guidance in writing this article.

- 1Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68:s1–106. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484

- 2Kennedy NA, Hansen R, Younge L, et al. Organisational changes and challenges for inflammatory bowel disease services in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020;11:343–50. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2020-101520

- 3Crohn’s and Colitis Care in the UK — The Hidden Cost and a Vision for Change. IBD UK. 2021.https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/improving-care-services/crohns-and-colitis-care-in-the-uk-the-hidden-cost-and-a-vision-for-change (accessed Oct 2021).

- 4Williams C, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, et al. Optimizing clinical use of mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) in inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4:237–48. doi:10.1177/1756283×11405250

- 5GREENFIELD SM, PUNCHARD NA, TEARE JP, et al. The mode of action of the aminosalicylates in inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2007;7:369–83. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00110.x

- 6Patel H, Barr A, Jeejeebhoy KN. Renal Effects of Long-Term Treatment with 5-Aminosalicylic Acid. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;23:170–6. doi:10.1155/2009/501345

- 7Octasa 800 mg modified-release tablets. Medicines Complete. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4479/smpc#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 8Sandborn WJ, Regula J, Feagan BG, et al. Delayed-Release Oral Mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800-mg Tablet) Is Effective for Patients With Moderately Active Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1934-1943.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.069

- 9Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Kornbluth A, et al. Delayed-Release Oral Mesalamine at 4.8 g/day (800 mg tablet) for the Treatment of Moderately Active Ulcerative Colitis: The ASCEND II Trial. Am J Gastroenterology. 2005;100:2478–85. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00248.x

- 10Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Dallaire C, et al. Delayed-Release Oral Mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800 mg tablets) Compared with 2.4 g/day (400 mg tablets) for the Treatment of Mildly to Moderately Active Ulcerative Colitis: The ASCEND I Trial. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;21:827–34. doi:10.1155/2007/862917

- 11Orchard TR, van der Geest SAP, Travis SPL. Randomised clinical trial: early assessment after 2 weeks of high-dose mesalazine for moderately active ulcerative colitis – new light on a familiar question. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2011;33:1028–35. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04620.x

- 12Mansfield JC, Giaffer MH, Cann PA, et al. A double-blind comparison of balsalazide, 6.75 g, and sulfasalazine, 3 g, as sole therapy in the management of ulcerative colitis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2002;16:69–77. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01151.x

- 13Lichtenstein GR, Kamm MA, Boddu P, et al. Effect of Once- or Twice-Daily MMX Mesalamine (SPD476) for the Induction of Remission of Mild to Moderately Active Ulcerative Colitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;5:95–102. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.025

- 14Levine DS, Riff DS, Pruitt R, et al. A randomized, double blind, dose-response comparison of balsalazide (6.75 g), balsalazide (2.25 g), and mesalamine (2.4 g) in the treatment of active, mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis1. Am J Gastroenterology. 2002;97:1398–407. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05781.x

- 15Pruitt R, Hanson J, Safdi M, et al. Balsalazide Is Superior to Mesalamine in the Time to Improvement of Signs and Symptoms of Acute Mild-to-Moderate Ulcerative Colitis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2002;97:3078–86. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07103.x

- 16Wang Y, Parker CE, Feagan BG, et al. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000544.pub4

- 17Ford AC, Khan KJ, Achkar J-P, et al. Efficacy of Oral vs. Topical, or Combined Oral and Topical 5-Aminosalicylates, in Ulcerative Colitis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107:167–76. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.410

- 18Marteau P. Combined oral and enema treatment with Pentasa (mesalazine) is superior to oral therapy alone in patients with extensive mild/moderate active ulcerative colitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Gut. 2005;54:960–5. doi:10.1136/gut.2004.060103

- 19Lim W-C, Wang Y, MacDonald JK, et al. Aminosalicylates for induction of remission or response in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008870.pub2

- 20Moja L, Danese S, Fiorino G, et al. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: comparative efficacy and safety of budesonide and mesalazine (mesalamine) for Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1055–65. doi:10.1111/apt.13190

- 21Akobeng AK, Zhang D, Gordon M, et al. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of medically-induced remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003715.pub3

- 22Summers R, Switz D, Sessions J, et al. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study: results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology 1979;77:847–69.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38176

- 23Malchow H, Ewe K, Brandes J, et al. European Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study (ECCDS): results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology 1984;86:249–66.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6140202

- 24Ulcerative colitis: management. NICE guideline [NG130]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng130 (accessed Oct 2021).

- 25Harris MS, Lichtenstein GR. Review article: delivery and efficacy of topical 5-aminosalicylic acid (mesalazine) therapy in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2011;33:996–1009. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04619.x

- 26Bernstein CN, Eaden J, Steinhart AH, et al. Cancer Prevention in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and the Chemoprophylactic Potential of 5-Aminosalicylic Acid. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2002;8:356–61. doi:10.1097/00054725-200209000-00007

- 27Kennedy NA, Jones G-R, Lamb CA, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidance for management of inflammatory bowel disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gut. 2020;69:984–90. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321244

- 28Ramamoorthy S, Cidlowski JA. Corticosteroids. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 2016;42:15–31. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2015.08.002

- 29Williams DM. Clinical Pharmacology of Corticosteroids. Respir Care. 2018;63:655–70. doi:10.4187/respcare.06314

- 30Truelove SC, Watkinson G, Draper G. Comparison of Corticosteroid and Sulphasalazine Therapy in Ulcerative Colitis. BMJ. 1962;2:1708–11. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5321.1708

- 31Chen J-H, Andrews JM, Kariyawasam V, et al. Review article: acute severe ulcerative colitis – evidence-based consensus statements. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:127–44. doi:10.1111/apt.13670

- 32Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;106:590–9. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.70

- 33Edsb??cker S, Andersson T. Pharmacokinetics of Budesonide (Entocort??? EC) Capsules for Crohn???s Disease. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 2004;43:803–21. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443120-00003

- 34Seidegård J, Nyberg L, Borgå O. Presystemic elimination of budesonide in man when administered locally at different levels in the gut, with and without local inhibition by ketoconazole. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2008;35:264–70. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2008.07.005

- 35Crohn’s disease: management. NICE guideline [NG129]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng129 (accessed Oct 2021).

- 36De Cassan C, Fiorino G, Danese S. Second-Generation Corticosteroids for the Treatment of Crohns Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: More Effective and Less Side Effects? Dig Dis. 2012;30:368–75. doi:10.1159/000338128

- 37D’Haens GR, Kovács Á, Vergauwe P, et al. Clinical trial: Preliminary efficacy and safety study of a new Budesonide-MMX® 9mg extended-release tablets in patients with active left-sided ulcerative colitis. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2010;4:153–60. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.007

- 38Prednisolone 5mg Suppositories. Medicines Complete. 2018.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9149/pil#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 39Entocort Enema. Medicines Complete. 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/873/smpc#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 40Budenofalk 2mg/dose rectal foam. Medicines Complete. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/237/smpc#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 41Andrisani G, Armuzzi A, Marzo M, et al. What is the best way to manage screening for infections and vaccination of inflammatory bowel disease patients? WJGPT. 2016;7:387. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i3.387

- 42Warner B, Johnston E, Arenas-Hernandez M, et al. A practical guide to thiopurine prescribing and monitoring in IBD. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2016;9:10–5. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2016-100738

- 43Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Hanauer SB. Ulcerative colitis. BMJ. 2013;346:f432–f432. doi:10.1136/bmj.f432

- 44GISBERT JP, LINARES PM, MCNICHOLL AG, et al. Meta-analysis: the efficacy of azathioprine and mercaptopurine in ulcerative colitis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2009;30:126–37. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04023.x

- 45Chande N, Patton PH, Tsoulis DJ, et al. Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000067.pub3

- 46Hazlewood GS, Rezaie A, Borman M, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Immunosuppressants and Biologics for Inducing and Maintaining Remission in Crohn’s Disease: A Network Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:344-354.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.011

- 47Imuran Tablets 25mg. Medicines Complete. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3822/smpc/print#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 48Azathioprine 50mg tablets. Medicines Complete. 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3301/smpc#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 49Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. The Lancet. 2009;374:1617–25. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61302-7

- 50Huang S-Z, Liu Z-C, Liao W-X, et al. Risk of skin cancers in thiopurines-treated and thiopurines-untreated patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2018;34:507–16. doi:10.1111/jgh.14533

- 51Annese V, Beaugerie L, Egan L, et al. European Evidence-based Consensus: Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Malignancies. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2015;9:945–65. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv141

- 52Moreau AC, Paul S, Del Tedesco E, et al. Association Between 6-Thioguanine Nucleotides Levels and Clinical Remission in Inflammatory Disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2014;20:464–71. doi:10.1097/01.mib.0000439068.71126.00

- 53Dubinsky MC, Lamothe S, Yang HY, et al. Pharmacogenomics and metabolite measurement for 6-mercaptopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:705–13. doi:10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70140-5

- 54ANSARI A, ARENAS M, GREENFIELD SM, et al. Prospective evaluation of the pharmacogenetics of azathioprine in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2008;28:973–83. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03788.x

- 55Wright S. Clinical significance of azathioprine active metabolite concentrations in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53:1123–8. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.032896

- 56Blaker PA, Arenas-Hernandez M, Smith MA, et al. Mechanism of allopurinol induced TPMT inhibition. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2013;86:539–47. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.06.002

- 57ANSARI A, PATEL N, SANDERSON J, et al. Low-dose azathioprine or mercaptopurine in combination with allopurinol can bypass many adverse drug reactions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2010;31:640–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04221.x

- 58SPARROW MP, HANDE SA, FRIEDMAN S, et al. Allopurinol safely and effectively optimizes tioguanine metabolites in inflammatory bowel disease patients not responding to azathioprine and mercaptopurine. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:441–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02583.x

- 59Lees CW, Irving PM, Beaugerie L. COVID-19 and IBD drugs: should we change anything at the moment? Gut. 2020;70:632–4. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323247

- 60Ungaro RC, Brenner EJ, Gearry RB, et al. Effect of IBD medications on COVID-19 outcomes: results from an international registry. Gut. 2020;70:725–32. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322539

- 61Kim H, Alten R, Avedano L, et al. The Future of Biosimilars: Maximizing Benefits Across Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. Drugs. 2020;80:99–113. doi:10.1007/s40265-020-01256-5

- 62Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2012;380:1909–15. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61084-8

- 63Williams JG, Alam MF, Alrubaiy L, et al. Infliximab versus ciclosporin for steroid-resistant acute severe ulcerative colitis (CONSTRUCT): a mixed methods, open-label, pragmatic randomised trial. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2016;1:15–24. doi:10.1016/s2468-1253(16)30003-6

- 64Van Assche G, D’haens G, Noman M, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of 4 mg/kg versus 2 mg/kg intravenous cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis1 1Gert Van Assche, Severine Vermeire, Geert D’Haens, and Paul Rutgeerts have been instrumental in the design of the study, trial management, data analysis, and writing the paper. Maja Noman had a major contribution in the clinical ambulatory follow-up of the patients in the trial. Martin Hiele followed cyclosporine levels and adjusted drug doses of patients in the trial and provided statistical advice. Katrien Asnong was the study coordinator and had a major share in data analysis. Joris Arts analyzed safety data and followed patients clinically during the trial. Andre D’Hoore and Freddy Penninckx performed the surgical interventions in patients failing the trial and substantially contributed in evaluating patients for colectomy. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1025–31. doi:10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01214-9

- 65Cheifetz AS, Stern J, Garud S, et al. Cyclosporine is Safe and Effective in Patients With Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2011;45:107–12. doi:10.1097/mcg.0b013e3181e883dd

- 66Sternthal MB, Murphy SJ, George J, et al. Adverse Events Associated With the Use of Cyclosporine in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am J Gastroenterology. 2008;103:937–43. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01718.x

- 67Shibata N, Ikuno Y, Tsubakimoto Y, et al. Adsorption and pharmacokinetics of cyclosporin A in relation to mode of infusion in bone marrow transplant patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:633–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bmt.1702196

- 68Regional Medicines Optimisation Committee (RMOC) Advisory Statement: Sequential Use of Biologic Medicines. SPS. 2020.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/rmoc-advisory-statement-sequential-use-of-biologic-medicines/ (accessed Oct 2021).

- 69Getting It Right First Time. Getting It Right First Time. 2021.www.gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/ (accessed Oct 2021).

- 70Kennedy NA, Heap GA, Green HD, et al. Predictors of anti-TNF treatment failure in anti-TNF-naive patients with active luminal Crohn’s disease: a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2019;4:341–53. doi:10.1016/s2468-1253(19)30012-3

- 71Remsima SC 120mg pre-filled pen. Medicines Complete. 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11101/smpc#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 72Humira 40mg/0.4ml solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Medicines Complete. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7986/smpc#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 73Simponi 100mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Medicines Complete. . 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5133#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 74Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, Azathioprine, or Combination Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–95. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0904492

- 75Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, et al. Trough Concentrations of Infliximab Guide Dosing for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1320-1329.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.031

- 76Adalimumab. British National Formulary. 2021.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/adalimumab.html (accessed Oct 2021).

- 77Colombel J-F, Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, et al. Four-Year Maintenance Treatment With Adalimumab in Patients with Moderately to Severely Active Ulcerative Colitis: Data from ULTRA 1, 2, and 3. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;109:1771–80. doi:10.1038/ajg.2014.242

- 78Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Sandborn WJ, et al. Adalimumab Induces and Maintains Mucosal Healing in Patients With Crohn’s Disease: Data From the EXTEND Trial. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1102-1111.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.035

- 79Plevris N, Lyons M, Jenkinson PW, et al. Higher Adalimumab Drug Levels During Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease Are Associated With Biologic Remission. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2018;25:1036–43. doi:10.1093/ibd/izy320

- 80Marehbian J, Arrighi HM, Hass S, et al. Adverse Events Associated With Common Therapy Regimens for Moderate-to-Severe Crohn’s Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2524–33. doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.322

- 81Mackey AC, Green L, Liang L, et al. Hepatosplenic T Cell Lymphoma Associated With Infliximab Use in Young Patients Treated for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition. 2007;44:265–7. doi:10.1097/mpg.0b013e31802f6424

- 82Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious Infections and Mortality in Association With Therapies for Crohn’s Disease: TREAT Registry. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2006;4:621–30. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.002

- 83Sazonovs A, Kennedy NA, Moutsianas L, et al. HLA-DQA1*05 Carriage Associated With Development of Anti-Drug Antibodies to Infliximab and Adalimumab in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:189–99. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.041

- 84Sazonovs A, Kennedy N, Moutsianas L, et al. HLA-DQA1*05 Carriage Associated With Development of Anti-Drug Antibodies to Infliximab and Adalimumab in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2020;158:189–99. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.041

- 85Park SC, Jeen YT. Anti-integrin therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. WJG. 2018;24:1868–80. doi:10.3748/wjg.v24.i17.1868

- 86Entyvio 108mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11361/smpc#gref (accessed Nov 2021).

- 87Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699–710. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1215734

- 88Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV Jr, et al. Vedolizumab versus Adalimumab for Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215–26. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1905725

- 89Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Vedolizumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–21. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1215739

- 90Wang MC, Zhang LY, Han W, et al. PRISMA—Efficacy and Safety of Vedolizumab for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Medicine. 2014;93:e326. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000000326

- 91Vaughn BP, Yarur AJ, Graziano E, et al. Vedolizumab Serum Trough Concentrations and Response to Dose Escalation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. JCM. 2020;9:3142. doi:10.3390/jcm9103142

- 92Vedolizumab for treating moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease after prior therapy. Technology appraisal guidance [TA352]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta352 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 93Vedolizumab for treating moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. Technology appraisal guidance [TA342]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta342 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 94TYSABRI 300 mg concentrate for solution for infusion. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/18447/SPC/TYSABRI+300+mg+concentrate+for+solution+for+infusion/#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 95STELARA 130mg concentrate for solution for infusion. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4412/smpc#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 96Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1946–60. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1602773

- 97Sands B, Sandborn W, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2019;381:1201–14. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602773

- 98Ustekinumab for moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease after previous treatment. Technology appraisal guidance [TA456]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta456 (accessed Oct 2021).

- 99Ustekinumab for treating moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. Technology appraisal guidance [TA633]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta633 (accessed Oct 2021).

- 100Ustekinumab. Crohn’s and Colitis UK. 2020.https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/about-crohns-and-colitis/publications/ustekinumab (accessed Oct 2021).

- 101De Vries LCS, Wildenberg ME, De Jonge WJ, et al. The Future of Janus Kinase Inhibitors in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2017;11:885–93. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx003

- 102XELJANZ 10 mg film-coated tablets. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9410/smpc#gref (accessed Oct 2021).

- 103Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. Tofacitinib as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723–36. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1606910

- 104Sands BE, Armuzzi A, Marshall JK, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib dose de-escalation and dose escalation for patients with ulcerative colitis: results from OCTAVE Open. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;51:271–80. doi:10.1111/apt.15555

- 105Lohan C, Diamantopoulos A, LeReun C, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: a systematic review, network meta-analysis and economic evaluation. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019;6:e000302. doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2019-000302

- 106Tofacitinib (Xeljanz▼): new measures to minimise risk of venous thromboembolism and of serious and fatal infections. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2020.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/tofacitinib-xeljanz-new-measures-to-minimise-risk-of-venous-thromboembolism-and-of-serious-and-fatal-infections (accessed Oct 2021).

- 107EMA confirms Xeljanz to be used with caution in patients at high risk of blood clots. European Medicines Agency. 2019.https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-confirms-xeljanz-be-used-caution-patients-high-risk-blood-clots (accessed Oct 2021).

- 108Xeljanz (tofacitinib): Initial clinical trial results of increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and malignancies (excluding NMSC) with use of tofacitinib relative to TNF-alpha inhibitors. Pfizer Limited. 2021.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/608683928fa8f51b9988cbb0/Xeljanz_tofacitinib_25_March_DHPC_2.pdf (accessed Oct 2021).

- 109Barkas F, Liberopoulos E, Kei A, et al. Electrolyte and acid-base disorders in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterol 2013;26:23–8.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24714322

- 110Neuman MG, Nanau RM. Inflammatory bowel disease: role of diet, microbiota, life style. Translational Research. 2012;160:29–44. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2011.09.001

- 111Weisshof R, Chermesh I. Micronutrient deficiencies in inflammatory bowel disease. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2015;18:576–81. doi:10.1097/mco.0000000000000226

- 112The Green Book. Public Health England. 2020.https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book#the-green-book (accessed Oct 2021).

- 113Alexander JL, Moran GW, Gaya DR, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a British Society of Gastroenterology Inflammatory Bowel Disease section and IBD Clinical Research Group position statement. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2021;6:218–24. doi:10.1016/s2468-1253(21)00024-8

- 114Live attenuated vaccines: avoid use in those who are clinically immunosuppressed. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2016.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/live-attenuated-vaccines-avoid-use-in-those-who-are-clinically-immunosuppressed (accessed Oct 2021).

- 115Hashash J, Kane S. Pregnancy and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2015;11:96–102.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27099578

- 116Ciobanu AM, Dumitru AE, Gica N, et al. Benefits and Risks of IgG Transplacental Transfer. Diagnostics. 2020;10:583. doi:10.3390/diagnostics10080583

- 117Matro R, Martin CF, Wolf D, et al. Exposure Concentrations of Infants Breastfed by Women Receiving Biologic Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Effects of Breastfeeding on Infections and Development. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:696–704. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.040

- 118Jones W. How to advise women on the safe use of medicines while breastfeeding. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2021;306. doi:10.1211/PJ.2021.1.83993

- 119Merlob P, Weber-Schöndorfer C, Peters P, et al. Immunosuppression, rheumatic diseases, multiple sclerosis, and WIlson’s disease. In: Schaefer C, ed. Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation (Third Edition). San Diego: : Academic Press 2015. 1–23.

- 120Merlob P, Weber-Schöndorfer C, Peters P, et al. Immunomodulating and antineoplastic agents. In: Schaefer C, ed. Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation (Third Edition). San Diego: : Academic Press 2015. 775–782.

- 121Freyer AM. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation 8th Edition: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. Obstet Med. 2009;2:89–89. doi:10.1258/om.2009.090002

- 122Götestam S, Hoeltzenbein M, Tincani A, et al. The EULAR points to consider for use of antirheumatic drugs before pregnancy, and during pregnancy and lactation. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:795–810. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208840

- 123Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). NCBI. 2006.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922 (accessed Oct 2021).

- 124Shanks A. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk, 10th Edition. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2015;72:1239–40. doi:10.1093/ajhp/72.14.1239

- 125Peters P, Miller R. Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation (Third Edition). San Diego: : Academic Press 2015.