SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the various causes of acute diarrhoea

- Elicit the necessary information to guide management

- Effectively manage patients presenting with acute diarrhoea

- Know when to refer patients for medical review

Diarrhoea is defined as the passage of three or more loose stools in 24 hours, or defecation more frequent than what is normal for an individual[1]. Diarrhoea can be classified as:

- Acute — symptoms lasting less than 14 days;

- Persistent — symptoms lasting more than 14 days; or

- Chronic — symptoms of more than 4 weeks duration[1].

This article discusses the diagnosis and management of acute diarrhoea and when pharmacists should refer patients for a further medical opinion.

Acute diarrhoea has a considerable impact on UK morbidity. Approximately 50% of acute diarrhoea patients report absence from work or school and around 25% of the UK population is affected by infectious diarrhoea annually[2,3]. During the winter months, gastroenteritis also carries a significant financial burden, costing the NHS an estimated £7m to £10m per year owing to resultant hospital bed closures and staff sickness[4].

Taking an accurate history is essential when assessing patients with diarrhoeal symptoms. The assessment should determine the onset, duration, frequency and severity of symptoms, the presence of any red flags and attempt to determine the underlying cause. It is also important to assess patients for complications, such as dehydration[4].

Symptoms

Children or adults presenting at a pharmacy with faecal urgency, abdominal cramps, abdominal pain, frequent passing of loose, watery faeces, nausea and/or vomiting need to be assessed carefully[4]. Immediate referral is required if the patient presents with any ‘Red flag’ symptoms and signs of significant disease, which are summarised in Box 1. Although most episodes of diarrhoea tend to be short lived, self limiting and benign, identifying cases that represent potentially serious illness can be a challenge[4].

Box 1: Red flag symptoms[5–8]

Patients presenting with ‘one or more’ of the following symptoms should be referred:

- Feeling generally unwell with fever and vomiting — risk of severe dehydration;

- Age <6 months with symptoms >24 hours duration — refer immediately and provide oral rehydration salts immediately;

- Infants with sunken fontanelle;

- Age >6 months with symptoms >48 hours duration;

- Vomiting or unable to tolerate oral rehydration;

- Pre-existing medical conditions worsened by diarrhoea (e.g. diabetes, congestive heart failure);

- Immunocompromised or on immunosuppressive medications;

- Abdominal pain;

- Blood or mucus in stool;

- Bleeding from rectum;

- Evidence of dehydration (e.g. skin turgor) or shock (e.g. tachycardia, systolic blood pressure <90mmHg, weakness, confusion, oliguria or anuria, marked peripheral vasoconstriction);

- Unintentional weight loss;

- Ongoing diarrhoea after recent completion of an antibiotic course;

- Nocturnal symptoms;

- Abdominal or rectal mass.

Pharmacists should use their clinical judgement when deciding on the urgency of the referral and whether it is necessary to refer to the GP or urgent care.

Aetiology

The majority (90%) of acute diarrhoea cases are associated with bacterial or viral infection[5]. Norovirus and Campylobacter are the most common diarrhoea-causing agents in the community[5]. Travellers’ diarrhoea can be caused by bacteria and parasites such as Escherichia coli, Campylobacter, Shigella and Salmonella[9].

Other causes of acute diarrhoea include food allergies (products containing sorbitol), alcohol, excess stress, recent pelvic irradiation, medication side effects (e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] or antibiotics) and acute flares of chronic inflammation, such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, which affect water reabsorption in the colon resulting in loose and/or watery stools[7].

There are many causes of acute diarrhoea in babies, most commonly viral gastroenteritis; however, the cause may be extra-intestinal (such as meningitis, chest infection, ear infection or a urinary tract infection)[5].

Assessment

Eliciting an accurate history of symptoms is the most effective way of diagnosing acute diarrhoea and will guide the choice of management. Box 2 summarises the questions pharmacists should ask to guide patient assessment.

Box 2: Questions to ask during a consultation with a patient experiencing diarrhoea

“When did it start?”

Onset of symptoms:

- Within one to two days of ingesting food suggests contaminated food (Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella or E. coli, Bacillus cereus toxin or norovirus)[10,11]

“What does it look like?”

Amount, consistency and frequency[12]:

- Higher volume and/or frequency of watery stools;

- Blood, mucus and/or pus in stools suggest severe inflammation and/or infectious cause;

- Mucus and pus indicate a chronic inflammatory cause or infective pathogen.

“How do you feel?”

Associated symptoms:

- Pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, fever, tenesmus;

- Thirsty but no appetite;

- What does the patient look like? Ill or well, nutritional status, fever?

“Where have you been recently?”

Travel, diet and lifestyle[6,9]:

- Recent travel or consumption of foods, such as meat, eggs, dairy or seafood, are suggestive of infection. Ask about any recent picnics or barbecues as well as water intake;

- Exposure to pets or cattle suggests infectious cause;

- Individuals who work in day care centres, hospitals or nursing homes suggests infection;

- Social history, such as sexual practice, alcohol use or drug use;

- Family history of cancer, irritable bowel disease (prevalence 0.5–1.0%), coeliac disease (prevalence of 0.5–1.0%) or irritable bowel syndrome (prevalence 10.0–13.0%).

Patients who are systemically unwell — such as those recently admitted to hospital and/or taking antibiotics, who have blood or pus in their stool, or who are immunocompromised — must be referred for further investigation involving routine microbiology of stool samples[3].

Testing for Clostridium difficile infection is also warranted for patients who have recently completed a course of antibiotics, are on a proton pump inhibitor, have been recently discharged from hospital, or have recently returned from foreign travel[7]. Additional testing for ova, cysts and parasites, including amoebae, Giardia or Cryptosporidium, is also recommended following travel abroad, particularly if diarrhoea is persistent (≥14 days) or the person has travelled to an at-risk area, such as Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and most parts of Asia[3,9]. Box 3 summarises the diet and personal hygiene measures travellers should follow to reduce their risk of developing travellers’ diarrhoea.

Patient advice

It is important that pharmacists provide patients and carers with the following advice to help manage symptoms[13].

Do:

- Stay at home and get plenty of rest;

- Drink lots of fluids, such as water or squash — take small sips if you feel sick;

- Eat when you feel able to — you do not need to eat or avoid any specific foods;

- Take paracetamol if you’re in discomfort — check the leaflet before giving it to a child.

- Carry on breast or bottle feeding your baby — if they’re being sick, try giving small feeds more often than usual;

- Give babies on formula or solid foods small sips of water between feeds;

Do not:

- Have fruit juice or fizzy drinks — they can make diarrhoea worse;

- Make baby formula weaker — prepare formula at its usual strength;

- Give children aged under 12 years medicine to stop diarrhoea;

- Give aspirin to children aged under 16 years.

If the patient works with older people or young children, they may pose a risk of passing on the infection. Provide infection prevention and control advice as summarised below[13]:

Do:

- Wash your hands with soap and water frequently;

- Wash any clothing or bedding that has faeces or vomit on it separately on a hot wash;

- Clean toilet seats, flush handles, taps, surfaces and door handles every day.

Do not:

- Prepare food for other people, if possible;

- Share towels, flannels, cutlery or utensils;

- Use a swimming pool until two weeks after the symptoms stop.

Return to work should be delayed until 48 hours after symptoms resolve and if symptoms do not improve or resolve within 1 week of onset, the patient should ring NHS 111 or visit their GP for further investigation of the cause[13].

Treatment

There is a high risk of dehydration associated with acute diarrhoea, particularly in young children, frail people and older people[5,7,14]. It is important to assess the level of dehydration (see Box 1) and determine whether referral is needed or if the patient can be safely managed with over-the-counter treatments, such as oral rehydration therapy (ORT). In severe dehydration (e.g. caused by dysentery and cholera), patients may require referral for intravenous hydration[5,7,14].

Oral rehydration therapy

Fluid and electrolyte depletion caused by diarrhoea is often prevented or reversed by ORT. Dehydration is the most common complication of acute diarrhoea and correction of hydration is best done with an orally administered low-osmolarity (i.e. hypotonic) alkaline rehydration solution containing glucose and sodium (240–250 mOsm/L)[5].

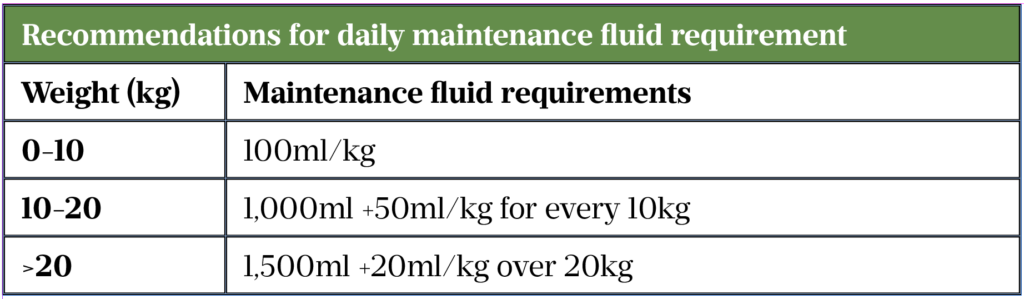

Each oral rehydration sachet (ORS) should be reconstituted with 200ml of water (freshly boiled and cooled water for children aged under 1 year) and may be kept at room temperature for up to 1 hour or in the fridge for up to 24 hours before discarding[5]. Frequent, small sips of refrigerated solutions may be more palatable and less likely to be regurgitated than giving a large volume quickly. When supplying ORS for children it may be helpful to provide an oral syringe for ease of administration. An alternative is to give the solution on a teaspoon or medicine spoon, or in a feeding bottle with a low flow teat. Administration of ORT to a healthy child is unlikely to cause any harm. Please see Table 1 for ORT recommendations.

Dosing of ORS in child with clinical dehydration = 50ml/kg over four hours plus maintenance fluids

Pharmacological treatment

Opiates

Antidiarrhoeal agents are mostly opioid based and should only be used for short-term, rapid control of symptoms (such as travellers’ diarrhoea), but should be avoided if infection suspected (see Case 1)[9]. Their use is limited by their actions on the central nervous system (CNS), which include CNS depression and the risk of dependence. Long-term use can also cause serious complications, such as toxic megacolon.

Loperamide is the antidiarrhoeal of choice for travellers, but should be avoided if blood or mucus is present in stools[9]. The recommended dosage is 4mg initially, followed by 2mg after each loose stool, up to 12mg a day for a maximum of 2 days if supplied over the counter or up to 16mg a day if prescribed [9]. In patients with short bowel syndrome, higher doses of orodispersible tablets should be prescribed owing to rapid intestinal transit times and minimal absorption[16]. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency reports serious cardiac adverse reactions at high doses and recommends caution[17]. Notable side effects include drowsiness, headache, constipation, nausea and flatulence.

Codeine increases the risk of colonic perforation if used in acute infective diarrhoea and should not be recommended[18,19]. However, in stoma patients with shorter transit time and reduced absorption, codeine is given at doses of 15–30mg up to every 4 hours, titrated to response[19]. Pharmacists should monitor patients for the usual opioid side effects, such as drowsiness and constipation[19].

Antimotility agents

Antimotility drugs should not be used in patients with a high fever or blood and/or mucus present in their stool (dysentery), or in confirmed E. coli (VTEC) or Shigellosis infections[20].

Co-phenotrope (atropine 25 micrograms and diphenoxylate 2.5mg) is licensed as an adjunct to rehydration in acute diarrhoea but effectiveness is debatable. The recommended dosage is four tablets initially followed by two tablets every six hours until diarrhoea is controlled[20].

Racecadotril, an enkephalinase inhibitor, is licensed as an adjunct to rehydration. It is currently not available in the UK for adults and the Scottish Medicines Consortium advised against the use in children owing to insufficient evidence[21].

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not recommended in view of the infection being most likely viral, but are occasionally used for prophylaxis of travellers’ diarrhoea (e.g. ciprofloxacin)[22].

Advice for continuing care

In most cases, acute diarrhoea symptoms resolve within five to seven days[7,13].

Individuals should not return to work until 48 hours after their symptoms have resolved[13]. If symptoms do not improve or resolve after a week, the patient should be referred for further investigation[13].

It is essential to maintain good hydration with ORT[13] and antidiarrhoeals must be stopped immediately if symptoms of ileus, constipation or abdominal distension are present[23].

Box 3: Diet and personal hygiene measures to prevent travellers’ diarrhoea[9]

Foods and beverages to be avoided while travelling:

- Raw or undercooked meats, fish and seafood;

- Unpasteurised milk, cheese, ice cream and other dairy products;

- Tap water and ice cubes;

- Cold sauces and toppings;

- Ground-grown leafy greens, vegetables and fruit;

- Cooked foods that have stood at room temperature in warm environments;

- Food from street vendors, unless freshly prepared and served piping hot.

Hygiene measures:

- Render water potable by either bringing it to a boil or treating it with chlorine or iodine preparations and filtering with a filter of 1μm or less;

- Wash hands before and after eating.

Case studies

Case 1: Adult patient with acute diarrhoea

A woman aged 39 years presents to her local pharmacy requesting loperamide and co-codamol.

Consultation

The woman reports up to 10 episodes of watery diarrhoea in the past 24 hours. There are no obvious signs of blood or mucus in her stool. She has no appetite, is thirsty and has occasional cramping but no other pain. She has two children at the local school and works as a community carer for older people. She needs to go back to work owing to staff shortages.

Assessment

Viral or bacterial infection is the most likely cause with some signs of dehydration, thirst and dizziness. Cramping mainly on emptying her bowels and no pain making a flare of chronic diarrhoea less likely. No possible underlying causes identified, such as any recent surgery, faecal incontinence or overflow diarrhoea resulting from constipation. She is not immunocompromised and has no history of chronic bowel disease. The patient is exhibiting no red flag symptoms, therefore referral to her GP is not required.

Advice

Recommend ORS as the mainstay of management and explain that acute diarrhoea usually resolves within five to seven days[15]. An antidiarrhoeal should be used with caution as acute diarrhoea is a defence mechanism and there is a risk of toxic megacolon. Antibiotics are not indicated without microbiological tests. Advise her to drink water and isotonic sports drinks (e.g. Lucozade) to provide potassium but to avoid hypertonic sugary or fizzy drinks, fruit juices and milk, which can worsen symptoms owing to damage to the intestinal lining caused by infecting organisms[13,24,25]. Recommend the consumption of easily digestible foods with high water content, such as soup or broth containing sodium. Provide infection prevention and control advice. Return to work should be delayed until 48 hours after symptoms resolve, and if symptoms do not improve or resolve within seven days of onset, she should visit her GP for further investigation of the cause[13].

Case 2: Paediatric patient

A woman comes into the pharmacy on a Saturday afternoon asking for advice on diarrhoea management for her son who is six months old. The mother states she has kept him home from nursery as he hasn’t quite been himself and is a bit clingier than usual. He is requesting breast feeds more frequently and urine in his nappy is dark yellow in colour.

Consultation

The mother says the baby has had watery diarrhoea for around 36 hours. He has no other medical conditions, is not receiving medication and she has not taken any actions so far. The baby has not vomited and has no fever, but looks quite pale with cold hands and has a slightly sunken fontanelle.

Diagnosis

The child is already at a high risk of dehydration owing to his age and is displaying signs of clinical dehydration, such as dark urine, pallor, cold hands and a sunken fontanelle. Other red flag symptoms, such as the duration of diarrhoea, warrant referral[5].

Advice

The mother should be signposted to the local out-of-hours GP or hospital emergency department for assessment, but she should be supplied with and advised on the use of ORS so that treatment can commence immediately in case of clinical delay.

Reassure her that diarrhoea is usually self-limiting and manageable at home with ORS and can last five to seven days, but that it should stop within two weeks[5]. Provide infection prevention and control advice, delay return to nursery until 48 hours after symptoms resolve and advise to keep away from swimming pools for two weeks. Advise not to make formula weaker or give fruit juice as it can make diarrhoea worse[13].

Case 3: Travellers’ diarrhoea

A 25-year-old male patient presents at the pharmacy with complaints of diarrhoea (approximately 5 times per day), abdominal pain and nausea for the past 3 to 4 days. He also complains of dry mouth, abdominal cramping and overall malaise. He states that he recently travelled to India on an adventure trip and has returned the day before.

Consultation

The patient did not receive any vaccinations or medications prior to travel and has not received antibiotics in the past five years. He reports no blood in the stool. He was on the return journey when the symptoms started so has not sought any professional advice.

Diagnosis

Travellers’ diarrhoea is, for most people, a short-lived, self-limiting illness with recovery in a few days [6]. If the patient complains of blood in the stool and intermittent fevers and dehydration, he should seek medical advice as soon as possible[9].

Advice

ORS is the treatment of choice for mild travellers’ diarrhoea[9]. As a rough guide, advise to drink at least 200ml after each watery stool. This extra fluid should be taken in addition to what the patient would normally drink[9]. If the patient is vomiting, advise to wait five to ten minutes and then start drinking again but more slowly. Advise them to take a sip every two to three minutes but make sure that the total intake is as described above[26,27].

It used to be advised to avoid eating for a while; however, it is now advised to eat small, light meals if possible, such as plain bread or rice. Continue with fluids and avoid fatty, spicy or ‘heavy’ food[9].

Loperamide or bismuth preparations can be considered for short-term treatment (two days). Advise the person not to use loperamide or bismuth subsalicylate if they have blood or mucus in the stool and/or high fever or severe abdominal pain, but seek medical advice[9].

This article was amended on 1 September 2021 to clarify that the codeine dose is every four hours, not up to 4 per hour, and the maximum daily dose of loperamide is 12mg when supplied over the counter and 16mg when prescribed.

Useful resources

- NHS: Diarrhoea and/or vomiting advice sheet (gastroenteritis) — advice for parents and carers of children

- National Travel Health Network and Centre (NATHAC): Travel health information aimed at healthcare professionals advising travellers and people travelling overseas from the UK

- NHS: Diarrhoea and vomiting

- www.patient.info: Travellers’ diarrhoea patient information

- www.patient.info: Gastroenteritis in children patient information

- www.patient.info: Food poisoning in children patient information

- Medicines for Children: Oral rehydration salts patient information leaflet

- 1Diarrhoeal disease fact sheet. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease (accessed Jul 2021).

- 2Sandmann FG, Jit M, Robotham JV, et al. Burden, duration and costs of hospital bed closures due to acute gastroenteritis in England per winter, 2010/11–2015/16. Journal of Hospital Infection 2017;97:79–85. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2017.05.015

- 3Managing Suspected Infectious Diarrhoea: Quick Reference Guide for Primary Care. Public Health England. 2015.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/409768/Managing_Suspected_Infectious_Diarrhoea_7_CMCN29_01_15_KB_FINAL.pdf (accessed Jul 2021).

- 4Arasaradnam RP, Brown S, Forbes A, et al. Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea in adults: British Society of Gastroenterology, 3rd edition. Gut 2018;67:1380–99. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315909

- 5Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis diagnosis, assessment and management in children younger than 5 years. NICE clinical guideline [CG84]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2009.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg84/resources/full-guideline-pdf-243546877 (accessed Jul 2021).

- 6Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut 2007;56:1770–98. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.119446

- 7Diarrhoea – adult’s assessment. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.https://cks.nice.org.uk/diarrhoea-adults-assessment#!topicSummary (accessed Jul 2021).

- 8Oral rehydration salts. Information for parents and carers leaflet. Medicines for Children. https://www.medicinesforchildren.org.uk/oral-rehydration-salts (accessed Jul 2021).

- 9Diarrhoea prevention advice for travellers. Clinical Knowledge Summary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/diarrhoea-prevention-advice-for-travellers/background-information/causes (accessed Jul 2021).

- 10Food poisoning. NHS Inform. https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/infections-and-poisoning/food-poisoning (accessed Jul 2021).

- 11BAM Chapter 14: Bacillus cereus. US Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bam-chapter-14-bacillus-cereus (accessed Jul 2021).

- 12Shane AL, Mody RK, Crump JA, et al. 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diarrhea. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017;65:e45–80. doi:10.1093/cid/cix669

- 13UK conditions: Diarrhoea and vomiting. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/diarrhoea-and-vomiting (accessed Jul 2021).

- 14Dehydration. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dehydration (accessed Jul 2021).

- 15Gastroenteritis. NICE clinical knowledge summary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://cks.nice.org.uk/gastroenteritis#!topicSummary (accessed Jul 2021).

- 16Owen S. Can high dose loperamide be used to reduce stoma output? . Specialist Pharmacy Service. 2019.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/UKMI_QA_Highdoseloperamide_updateSep-2018_FINAL_partial-update-Mar2019.pdf (accessed Jul 2021).

- 17Loperamide (Imodium): reports of serious cardiac adverse reactions with high doses of loperamide associated with abuse or misuse. Gov.uk. 2017.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/loperamide-imodium-reports-of-serious-cardiac-adverse-reactions-with-high-doses-of-loperamide-associated-with-abuse-or-misuse (accessed Jul 2021).

- 18Codeine phosphate 15mg tablets BP. Summary of product characteristics. Aurobindo Pharma – Milpharm Ltd. . medicines.org. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11268 (accessed Jul 2021).

- 19Pharmaceutical considerations for patients with stomas. Pharmaceutical Journal Published Online First: 2020. doi:10.1211/pj.2020.20208146

- 20Co-phenotrope drug monograph. British National Formulary. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/co-phenotrope.html (accessed Jul 2021).

- 21SMC advice racecadotril 10mg, 30mg granules for oral suspension (Hidrasec Infants®, Hidrasec Children®)SMC No.(818/12). Scottish Medicines Consortium. 2014.https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/medicines-advice/racecadotril-hidrasec-resubmission-81812 (accessed Jul 2021).

- 22Diarrhoea (acute) treatment summary. British National Formulary. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/diarrhoea-acute.html (accessed Jul 2021).

- 23Cipla EU L. Loperamide 2mg Capsules. Summary of product characteristics. medicines.org.uk. 2020.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10287/smpc (accessed Sep 2021).

- 24Knott L. Gastroenteritis. Patient. 2017.https://patient.info/digestive-health/diarrhoea/gastroenteritis (accessed Jul 2021).

- 25Lactose intolerance Causes. NHS. 2019.https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/lactose-intolerance/causes (accessed Jul 2021).

- 26Hill DR, Ryan ET. Management of travellers’ diarrhoea. BMJ 2008;337:a1746–a1746. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1746

- 27Traveller’s diarrhoea. Patient. https://patient.info/travel-and-vaccinations/travellers-diarrhoea-leaflet (accessed Jul 2021).