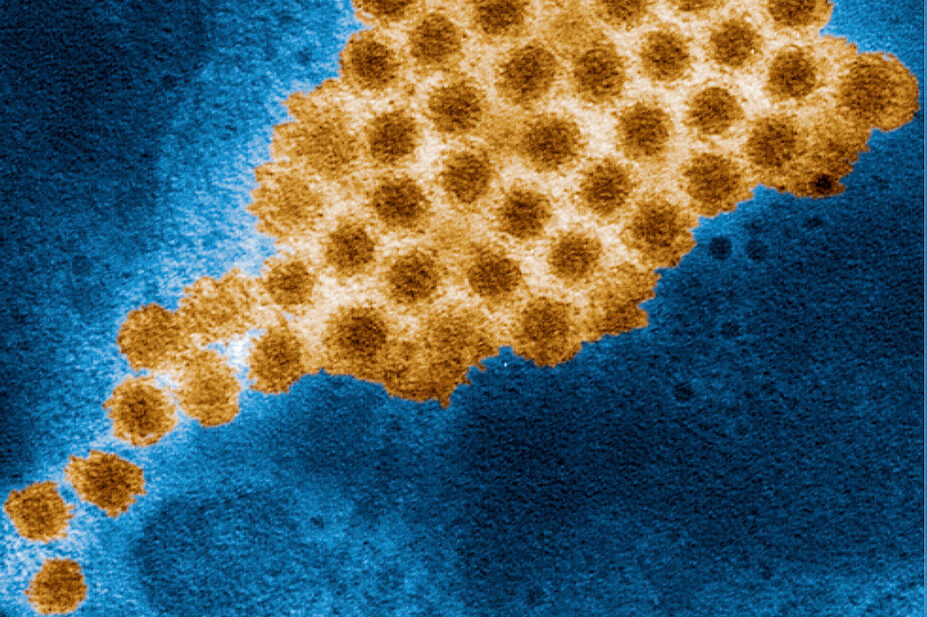

BSIP SA/Alamy Stock Photo

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Recognise the clinical signs and symptoms of norovirus infection;

- Know which patients are vulnerable to contracting norovirus infection;

- Understand the role of the infection control team in managing norovirus infections;

- Understand the strategies to prevent transmission, treat and control the infection.

Norovirus, often colloquially referred to as the ‘winter vomiting bug’, is one of the leading causes of acute gastroenteritis worldwide. While typically self-limiting, it represents a substantial public health burden, particularly in vulnerable groups and institutional settings, such as hospitals and care homes.

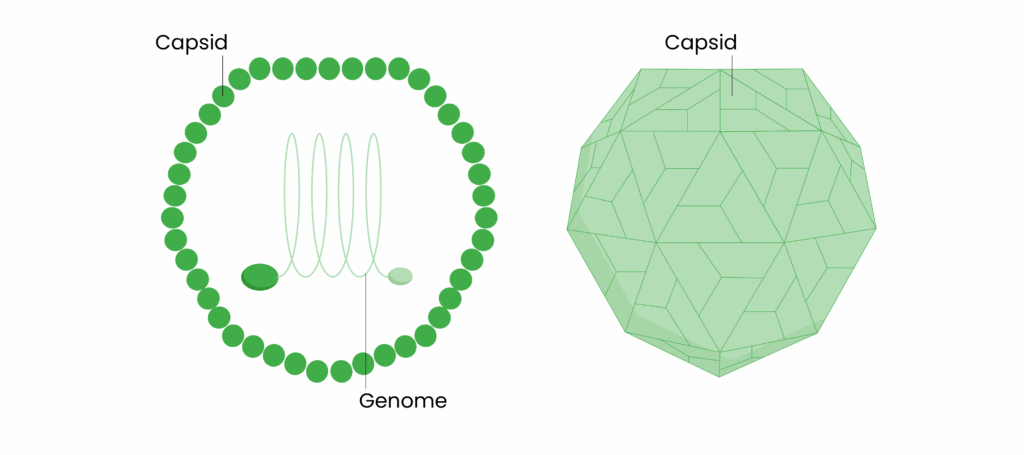

Norovirus is a highly contagious, enteric non-enveloped virus belonging to the Caliciviridae family and norovirus genus (see Figure). It is highly stable under extremely hostile conditions, including a range of pHs (3–7) and temperatures as high as 60°C1. These factors give some indication of the difficulty of eradicating and controlling the spread of norovirus infection.

Figure: The structure of norovirus

Norovirus is a leading cause of waterborne and foodborne acute gastroenteritis worldwide, responsible for approximately 18% of all diarrheal disease and around 200,000 deaths annually1. It causes approximately 685 million cases of gastroenteritis each year, including 200 million in children aged under five years, resulting in over 200,000 deaths annually, mainly in low and middle-income countries2–4.

In the UK, an estimated 3 million people are affected by norovirus annually, equating to about 47 cases per 1,000 population5. There was a sharp rise in cases in the 2024/2025 season, with 548 outbreaks reported in NHS acute hospitals during that time — 56.5% higher than the five-season average of 3506. A daily average of 784 hospitalised patients was recorded early in the 2024/2025 season, peaking at 1,160 patients by mid-February — more than double the figure from the previous year7,8.

Norovirus is not a notifiable disease in England and, owing to its often mild symptoms, many cases go unreported9. Nonetheless, laboratory-confirmed reports during 2024/2025 showed an earlier onset and prolonged season stretching into spring and summer.

The factors likely to have contributed to this were:

- Post-pandemic changes in population immunity;

- Changes in diagnostic testing capabilities;

- Changes in reporting to national surveillance; and

- A true rise in norovirus transmission owing to the emergence of GII.1710.

At-risk populations

Certain populations are especially vulnerable to severe or prolonged norovirus infection:

- Young children, particularly those aged under five years11;

- Older adults, especially those in care homes12;

- Immunocompromised individuals13;

- Healthcare workers and residents in institutional settings14;

- Closed communities such as cruise ships, prisons or military barracks15.

Seasonality and transmission

Norovirus peaks during winter months in temperate climates16. It spreads primarily through person-to-person contact, contaminated food or water and touching contaminated surfaces.

With a very low infectious dose and the ability to survive on surfaces for days or even weeks, the virus is notoriously hard to control17,18.

Clinical features

Norovirus is subdivided into multiple genogroups. Genogroups GI, GII, GIV, GVIII and GIX include human pathogens. The most common cause of human norovirus infection is GII, mostly GII.4, followed by other types such as GII.2 and GII.17, followed by GI and GIV. The GII.4 viruses have been highly predominant and associated with more severe outcomes than other norovirus genotypes, including higher hospitalisation and death rates1.

Less than 100 viral particles are sufficient to cause infection. Viral shedding is at maximum in the first 24–48 hours after onset of illness. Average shedding duration is 4 weeks; in immunocompromised patients, viral shedding can persist for months. The transmission of the virus occurs via faecal-oral route, airborne droplets from vomit, contaminated food or water1.

Norovirus replicates in the small intestinal epithelium. Although detailed molecular mechanisms are still under study, its stability and mutational capacity contribute to continued transmission and outbreak19,20.

Typical symptoms include:

- Nausea;

- Vomiting;

- Abdominal cramping;

- Diarrhoea;

- Myalgias;

- Headache;

- Chills.

Symptom onset usually occurs within 12–48 hours of exposure and symptoms typically last 1–3 days19,20.

Complications, such as dehydration, are most common among vulnerable populations, which include mainly older adults, infants aged <12 months and immunocompromised patients. In patients with severe disease, fever is common and the illness may last several days longer than in healthy people.

Strategies for prevention, treatment and control

Effective prevention strategies include:

- Hand hygiene after using the toilet or before handling food. Handwashing with soap and water is more effective than alcohol-based hand sanitisers for removing norovirus particles19,20;

- Alcohol-based sanitisers work by dissolving lipid membranes, meaning that norovirus is resistant to alcohol-based sanitisers owing to its tough protein capsid (see Figure) and lack of lipid envelope that makes it difficult to be inactivated by alcohol1;

- Surface disinfection using bleach-based products15;

- Following food safety practices, such as cooking shellfish thoroughly21.

Treatment approaches

There is no specific antiviral treatment for norovirus. Management is mainly supportive, including:

- Oral or IV fluid replacement. Oral rehydration therapy is recommended in mild-to-moderate dehydration, especially in children, to maintain the balance of salts and sugars. Patients should be monitored for signs of dehydration, such as reduced urination. IV fluids are indicated for patients who are hospitalised and cannot keep up with the losses owing to vomiting or severe diarrhoea, or for those at increased risk, including infants, older people and immunosuppressed patients;

- Rest and isolation at home until 48 hours symptom free22;

- Education of hygiene practices, such as hand hygiene, surface disinfection, safe cooking practices and the washing of food products.

Role of the pharmacist in managing infection

Pharmacists can educate patients and caregivers on hydration strategies and supportive symptomatic care. For instance, pharmacists can guide a patient or caregiver in selecting appropriate rehydration or electrolyte replacement options. It is also important that pharmacists explain that antibiotics are not indicated for viral gastroenteritis. This is a crucial educational point to help prevent the inappropriate use of antibiotics and aligns with the principles of antimicrobial stewardship.

Pharmacists can also provide accurate information about hand hygiene and environmental cleanliness, acting as front-line educators for prevention. Community pharmacists frequently encounter patients seeking advice, such as parents looking for ways to treat children with a stomach bug. They have the ideal opportunity to reiterate the importance of proper hand hygiene measures, such as hand-washing after nappy changes and before eating.

Pharmacists in institutional settings, such as hospitals, can support infection control teams by monitoring and managing the supply needs of a ward area during outbreaks to prevent cross-contamination. For instance, they could ensure high stock levels of IV fluids for wards that experience outbreaks of norovirus.

Role of the infection control team

The infection control team is a specialised group that consist of doctors, nurses, pharmacists and microbiologists within a hospital or healthcare system that are responsible for the prevention and management of the spread of infections among patients, staff and visitors. In the context of norovirus, they are responsible for coordinating and enforcing actions required to contain norovirus during an outbreak.

The team lead implementation of outbreak protocols and develops and enforces policies and procedures related to norovirus outbreaks and cleaning requirements that limits further spread of the infection. These include:

- Isolating symptomatic individuals for 48 hours after symptoms stop23;

- Deep cleaning affected areas with appropriate disinfectants;

- Cohorting staff and restricting movement between wards;

- Temporary ward closures10.

The infection control team will also coordinate case finding, surveillance and isolation practices and monitor for clusters of symptomatic patients. For instance, if two or more patients on a ward suddenly develop vomiting and diarrhoea within 48 hours, ward staff are instructed to notify the infection control team. This allows the rapid identification of a possible norovirus outbreak, and early intervention reduces the further spread of infection.

The infection control team is also responsible for training healthcare staff and managing visitor restrictions during outbreaks to prevent further spread of the infection in the community.

Conclusion

Norovirus remains a major cause of acute gastroenteritis and places a significant burden on the healthcare system, especially in winter. While treatment is currently limited to supportive care, ongoing research into vaccines and antivirals offers hope for more effective prevention and control strategies in the future. Public health efforts must continue to focus on hygiene, outbreak management and surveillance to limit the impact of the virus, especially in patient groups at most risk.

Best practice for pharmacists

- Provide education for patients on hydration strategies, appropriate oral rehydration options and symptom management, especially for patients at higher risk of dehydration and complications;

- Support antimicrobial stewardship by reinforcing to patients that antibiotics are not indicated for viral gastroenteritis;

- Educate patients about the importance of hand hygiene, especially emphasising the use of soap and water handwashing rather than alcohol-based sanitisers, especially after nappy changes for those looking after babies, using the toilet, when cooking to prevent cross-contamination, and before eating;

- Advise on the importance of environmental cleanliness, emphasising the use of bleach-based disinfectants for cleaning contaminated surfaces, because alcohol-based cleaners are ineffective against norovirus.

- 1.O’Ryan MG. Norovirus. Up To Date. November 2025. Accessed January 2026. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/norovirus?search=NOROVIRUS&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~57&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H30

- 2.Ahmed SM, Hall AJ, Robinson AE, et al. Global prevalence of norovirus in cases of gastroenteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(8):725-730. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(14)70767-4

- 3.Burden of norovirus illness in the US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2023. Accessed January 2026. https://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/trends-outbreaks/burden-US.html

- 4.Norovirus worldwide. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2023. Accessed January 2026. https://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/trends-outbreaks/worldwide.html

- 5.Tam CC, Rodrigues LC, Viviani L, et al. Longitudinal study of infectious intestinal disease in the UK (IID2 study): incidence in the community and presenting to general practice. Gut. 2011;61(1):69-77. doi:10.1136/gut.2011.238386

- 6.National norovirus and rotavirus report: Week 23. UK Health Security Agency. 2025. Accessed March 2026. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-norovirus-and-rotavirus-surveillance-reports-2024-to-2025-season

- 7.Surge in norovirus cases keeps pressure on hospitals high. NHS England. January 2025. Accessed January 2026. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2025/01/surge-in-norovirus-cases-keeps-pressure-on-hospitals-high/

- 8.Record number of norovirus patients in hospital. NHS England. February 2025. Accessed January 2026. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2025/02/record-number-of-norovirus-patients-in-hospital/

- 9.BioMed Central . BMC Public Health. 2024. Accessed January 2026. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/

- 10.Why is norovirus reporting in England so high? UK Health Security Agency. November 2024. Accessed January 2026. https://ukhsa.blog.gov.uk/2024/11/29/why-is-norovirus-reporting-in-england-so-high-at-the-moment/

- 11.Payne DC, Vinjé J, Szilagyi PG, et al. Norovirus and Medically Attended Gastroenteritis in U.S. Children. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(12):1121-1130. doi:10.1056/nejmsa1206589

- 12.Increase in norovirus outbreaks in hospitals in England and Wales, 2002–2003 (holding reference). Emerging Infectious Diseases. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1001.030431

- 13.Green K. Caliciviridae: The noroviruses. In: Fields Virology . 6th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2013:2664. Accessed January 2026. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/ovid/fields-virology-6th-edition-15514

- 14.Hall AJ, Lopman BA, Payne DC, et al. Norovirus Disease in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(8):1198-1205. doi:10.3201/eid1908.130465

- 15.Freeland AL, Vaughan GH Jr, Banerjee SN. Acute Gastroenteritis on Cruise Ships — United States, 2008–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(1):1-5. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6501a1

- 16.Mounts AW, Ando T, Koopmans M, Bresee JS, Noel J, Glass RI. Cold Weather Seasonality of Gastroenteritis Associated with Norwalk‐like Viruses. J INFECT DIS. 2000;181(s2):S284-S287. doi:10.1086/315586

- 17.Teunis PFM, Moe CL, Liu P, et al. Norwalk virus: How infectious is it? Journal of Medical Virology. 2008;80(8):1468-1476. doi:10.1002/jmv.21237

- 18.Updated Norovirus Outbreak Management and Disease Prevention Guidelines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . March 2011. Accessed January 2026. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6003a1.htm

- 19.Norovirus: Guidance and surveillance. UK Health Security Agency. 2024. Accessed January 2026. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/norovirus-guidance-data-and-analysis

- 20.Preventing norovirus infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Accessed January 2026. https://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/preventing-infection.html

- 21.Norovirus. Food Standards Agency. 2022. Accessed January 2026. https://www.food.gov.uk/safety-hygiene/norovirus

- 22.Norovirus (vomiting bug). NHS. 2023. Accessed January 2026. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/norovirus/

- 23.Norovirus: Guidance, data and analysis. Public Health England. 2017. Accessed January 2026. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/norovirus-guidance-data-and-analysis

You might also be interested in…

Everything you need to know about mpox

Case-based learning: insect bites and stings