Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the mechanism of action for SGLT2 inhibitors and their role in the management of indicated conditions;

- Identify the benefits and risks associated with the inpatient use of SGLT2 inhibitors to make informed decisions about the appropriateness of prescribing;

- Know the monitoring requirements for SGLT2 inhibitors to mitigate risk and ensure the safe and effective use of SGLT2 inhibitors;

- Appreciate the importance of collaboration within the multidisciplinary team and cross-speciality, when indicated, to meet individual patient needs.

Introduction

Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors act on the renal proximal convoluted tubule, which inhibits SGLT2, to reduce the absorption of sodium and glucose into the blood and encourage their excretion in urine1. These medicines have shown to improve glycaemic control, lower HbA1c and encourage weight reduction in people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)1.

SGLT2 inhibitors have the potential to improve cardiovascular outcomes, demonstrating blood pressure control and symptom relief of heart failure (HF), as well as presenting clinical benefits for those living with chronic kidney disease (CKD)1. These cardiorenal benefits can be attributed to the natriuretic properties of SGLT2 inhibitors in reducing blood volume and blood pressure by around 4–6mmHg systolic and 1–2mmHg diastolic on average2. Dapagliflozin and empagliflozin are the most commonly prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors and are licensed for the following indications:

- In patients with T2DM as monotherapy when metformin is considered inappropriate or not tolerated;

- In patients with T2DM as an adjunct with other glucose-lowering medicines;

- For CKD, as outlined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance, with consideration of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR);

- For symptomatic chronic HF3–7.

Canagliflozin and ertugliflozin are licensed for T2DM only4–7.

An array of large-scale, randomised studies demonstrates statistically significant relative reductions in cardiorenal events with the prescribing of an SGLT2 inhibitor compared with placebo8,9. In 2020, results of the dapagliflozin–CKD study presented a 39% risk reduction of renal function decline with dapagliflozin compared with placebo, regardless of the presence or absence of T2DM10. Similarly, results of the dapagliflozin–HF study, published in 2019, presented the merit of dapagliflozin compared to placebo (in the presence or absence of T2DM), where a 25% risk reduction was observed for cardiovascular death and hospitalisations owing to HF11. The cost-effectiveness of SGLT2 inhibitors has been proven by their efficacy to lower serum glucose and improve renal and cardiovascular outcomes to minimise costly clinical events and improve quality of life8,9.

A blanket approach for suspending SGLT2 inhibitors for all inpatients, regardless of the presenting complaint, was adopted within Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals (NuTH), owing to safety concerns raised by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) regarding the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). NuTH has regularly updated its Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust internal guideline on these concerns since April 20168,12. This approach differs from surrounding service providers, who continued prescribing unless contraindicated and assessed the clinical presentation on admission as to whether prescribing or suspending the SGLT2 inhibitor was appropriate. In addition, hospital admission alone was not deemed a barrier to prescribing. The MHRA has advised to “interrupt SGLT2 inhibitor treatment in patients who are hospitalised for major surgery or acute serious illnesses; treatment may be restarted once the patient’s condition has stabilised”12. As the risk of DKA is increased for those diagnosed with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), the use of SGLT2 inhibitors is contraindicated12. The development of DKA, during acute illness, may occur owing to an increase in cortisol that contributes to insulin resistance9. Furthermore, glycosuria induced by SGLT2 inhibitors causes a reduction in carbohydrate stores and promotes the oxidation of fat and ketogenesis, which increases the risk of DKA13,14.

As the evidence base supporting the use of SGLT2 inhibitors for glucose-lowering properties and cardiorenal benefits continues to grow, alongside a UK population with increasing prevalence of T2DM, obesity and associated cardiovascular and renal disease, the incidence of prescribing these medicines increases8,9. During a patient’s hospitalisation, pharmacists can provide counselling on the use or suspension of SGLT2 inhibitors, analysis of blood test results (including serum ketones in this instance) and the prescribing of SGLT2 inhibitors if they are registered as a prescriber and are competent to do so. As a result, it is important that pharmacists have the support and guidance they need to appropriately prescribe and monitor these medicines in hospitalised patients9.

This article will outline how SGLT2 inhibitor use can be evaluated in hospitalised patients, allowing a well-balanced approach that means patients can continue to benefit from SGLT2 inhibitors, where appropriate, while managing and reducing the risk of DKA.

Local audit

The authors conducted an audit within the NuTH pharmacy department to identify a practical prescribing approach for SGLT2 inhibitors in hospital, in accordance with the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust internal guideline, which had adopted the blanket approach of suspending SGLT2 inhibitors during hospitalisation. Crucial findings from this audit include the suspension of SGLT2 inhibitors for 85% (n=150) of the sample population (76% of whom were diagnosed with T2DM and were considered at risk of DKA), appropriate monitoring was conducted for 9% of the sample population and documentation that medicines counselling had been conducted for 8% of the sample population. Results from the audit revealed that SGLT2 inhibitors were prescribed inappropriately or unnecessarily suspended for 33% of the population, largely owing to the blanket approach. The findings encouraged an update of the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust internal guideline to support clinicians with the appropriate prescribing of these medicines, in consideration of the risks and benefits of treatment, to ensure clinical excellence and patient-centred care. This update to the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust internal guideline aims to ensure that patients who do not present a risk of developing DKA can continue to benefit from their medicines1.

Prescribing considerations

Table 1 presents the contraindications and cautions associated with the prescribing of SGLT2 inhibitors for all patients, regardless of the prescribing indication, which should be assessed in the first instance9,15,16.

Table 1: The contraindications and cautions for all patients prescribed an SGLT2 inhibitor9,15,16

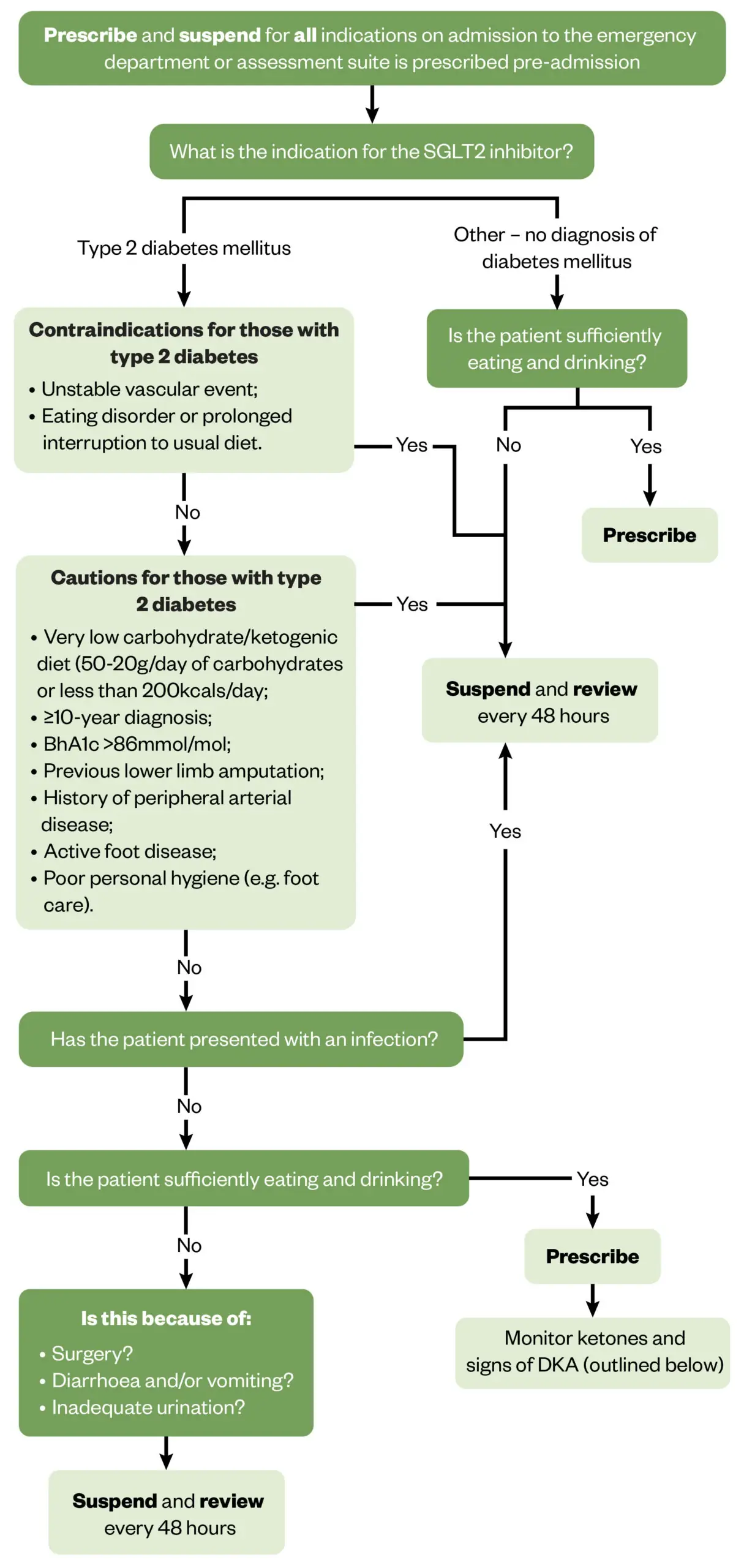

Considerations that pharmacists should take into account when deciding whether to prescribe or suspend an SGLT2 inhibitor surrounds the ability of the patient to tolerate oral intake and/or cope with acute stress on the body, such as in the event of surgery or infection, which includes vomiting and diarrhoea12. These considerations can be explained by the mechanism of DKA development, as explored earlier, and should be evaluated on an individual patient basis, using Figure 1 for support9,15,16.

The updated Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust internal guideline advises that SGLT2 inhibitors are suspended while awaiting medical review in A&E and admissions assessment suite, as well as for the appropriateness of prescribing to be evaluated on base wards where close monitoring can be conducted (see Figure 1). This was a collaborative decision made by the multidisciplinary team (MDT) within renal, cardiology and endocrinology specialities to manage potential risks associated with the prescribing of SGLT2 inhibitors and maximise clinical outcomes for all patients. MDT collaboration is important with the review of these medicines, especially when the patient is under the care of multiple specialties — such as renal, cardiology and/or endocrinology — to ensure the medicine is safe and effective for the management of all indicated conditions.

Figure 1 presents considerations to aid the decision-making process on whether to prescribe or suspend the SGLT2 inhibitor during hospital admission for an individual. A medication review is undertaken ideally within the first 48 hours of admission and then as frequently as deemed clinically required, which is based on individual presentation. The medication review includes the consideration of the presenting complaint, analysis of blood test results and observations, as well as drug interactions. The patient should be medically reviewed as per Figure 1 and monitored appropriately. A review every 48 hours may include repeat blood tests in accordance with the presenting complaint and observations, as well as oral intake to inform the decision on whether to prescribe or suspend the SGLT2 inhibitor.

Figure 1: Decision-making considerations for the safe and effective prescribing of SGLT2 inhibitors in hospital patients9,15,16

The Pharmaceutical Journal (based on Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust internal guideline)

Monitoring

Serum ketone monitoring should be conducted within 24 hours of admission, even when the plasma glucose concentration is normal (euglycaemic), owing to the potential for euglycaemic DKA14,17. Thereafter, serum ketones should be measured every 24–48 hours as part of routine monitoring or immediately if there is a clinical suspicion of euglycaemic DKA. SGLT2 inhibitors should be suspended and not restarted if DKA is confirmed12,14. The signs of DKA are also discussed under patient counselling. If the initial serum ketones are <1 mmol/L, with <0.6 mmol/L considered normal and the SGLT2 inhibitor is suspended, there is no need to repeat ketone monitoring unless there is a clinical concern. Serum ketone monitoring is preferred to urinary monitoring, owing to improved accuracy, and it has been suggested that ketones in the urine may be reabsorbed2,12.

Adverse effects

In addition to the risk of developing DKA, SGLT2 inhibitors have the potential to cause other adverse effects that must be considered and strategies must be implemented to mitigate the risks, particularly for hospitalised patients who may be more vulnerable. Table 2 outlines some of these adverse effects and how they can be treated or prevented1,6,13,18,19.

Table 2: Potential adverse effects of SGLT2 inhibitors1,6,13,18,19

Patient case study

A 44-year-old female was admitted to the acute cardiology ward with a background of T2DM and HF, having experienced an increase in shortness of breath and peripheral oedema. Dapagliflozin 10mg daily was prescribed pre-admission, providing benefits for both indications.

Using Table 1 and Figure 1, the appropriateness of continuing dapagliflozin during the hospital admission was assessed:

- No cautions or contraindications presented; for example, the HbA1c was 53 mmol/mol, and there were no concerns of vascular disease and no disruption to oral intake, particularly carbohydrates;

- No presentation of infection, including fever and blood markers;

- Sufficient eating and drinking were observed during admission;

- No surgery planned;

- Diarrhoea or vomiting was not observed;

- Adequate urination observed (closely monitored with increasing the dose of diuretics).

Owing to the prescribing of antihypertensives and diuretics, hypotension and hypovolaemia were monitored alongside renal function (eGFR 50 mL/min/1.73m2), ketones (0.4 mmol/L) and blood glucose (8 mmol/L), while the SGLT2 inhibitor was prescribed during hospital admission.

Patient counselling

Patients should be counselled on the importance of personal hygiene, hydration and signs of hypoglycaemia, if relevant. This also applies to other potential adverse effects (as outlined above) to allow healthcare professionals to make an informed decision about prescribing the SGLT2 inhibitor, or not, and to rapidly respond to complications if they occur. Counselling is relevant for patients, both during their hospital admission and on discharge, but healthcare professionals are more readily available to be contacted for support during hospitalisation.

Healthcare professionals should also counsel patients on the signs of DKA, which can include nausea, vomiting, rapid breathing, abdominal pain, fever, stupor, fatigue, rapid weight loss, sleepiness, sweet smelling breath, sweet or metallic taste in the mouth and a different odour to urine and/or sweat9. DKA is a medical emergency, so patients and healthcare professionals should remain vigilant and treatment initiated if indicated using local or NuTH guidance14,17. Additional information on the management of DKA can be found in ‘Diabetic ketoacidosis in adults: identification, diagnosis and management’20. In addition, patients should be advised on the ‘sick day rules’ to suspend the SGLT2 inhibitor, in the event of acute illness where oral intake is compromised, such as in the case of diarrhoea and/or vomiting in the community, and consider monitoring blood glucose and ketones1,14.

Best practice points

- Education on the benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors to support compliance and the risks of treatment allows patients and healthcare professionals to make informed decisions about the suitability of treatment and promotes vigilance for adverse effects;

- Risk mitigation and maximised outcomes are achieved with best monitoring and counselling practices, with support from relevant specialities involved in individual patient care;

- A blanket approach demonstrates merit in risk management but has the potential to disadvantage patients who would benefit from continued treatment — thus, review on an individual patient basis ensures that individual needs are met.

Useful resources from The Pharmaceutical Journal

- 1.Chan JCH, Chan MCY. SGLT2 Inhibitors: The Next Blockbuster Multifaceted Drug? Medicina. 2023;59(2):388. doi:10.3390/medicina59020388

- 2.Heerspink HJL, Perkins BA, Fitchett DH, Husain M, Cherney DZI. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation. 2016;134(10):752-772. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.116.021887

- 3.Chronic kidney disease: Scenario: Management of chronic kidney disease. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. September 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/chronic-kidney-disease/management/management-of-chronic-kidney-disease/

- 4.Forxiga 10 mg film-coated tablets. AstraZeneca UK. September 24, 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7607/smpc#gref

- 5.Jardiance 10 mg film-coated tablets. Boehringer Ingelheim Limited. July 19, 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5441/smpc

- 6.Invokana 100 mg film-coated tablets. A. Menarini Farmaceutica Internazionale SRL. October 11, 2023. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8855/smpc

- 7.Steglatro 5 mg Film-Coated Tablets. Merck Sharp & Dohme (UK) Limited. April 13, 2022. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9803/smpc

- 8.Seidu S, Alabraba V, Davies S, et al. SGLT2 Inhibitors – The New Standard of Care for Cardiovascular, Renal and Metabolic Protection in Type 2 Diabetes: A Narrative Review. Diabetes Ther. 2024;15(5):1099-1124. doi:10.1007/s13300-024-01550-5

- 9.Wilding JPH, Evans M, Fernando K, et al. The Place and Value of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in the Evolving Treatment Paradigm for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13(5):847-872. doi:10.1007/s13300-022-01228-w

- 10.Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1436-1446. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2024816

- 11.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):1995-2008. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1911303

- 12.Dapagliflozin. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2024. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/dapagliflozin/

- 13.van Baar MJB, van Ruiten CC, Muskiet MHA, van Bloemendaal L, IJzerman RG, van Raalte DH. SGLT2 Inhibitors in Combination Therapy: From Mechanisms to Clinical Considerations in Type 2 Diabetes Management. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(8):1543-1556. doi:10.2337/dc18-0588

- 14.Chow E, Clement S, Garg R. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis in the era of SGLT-2 inhibitors. BMJ Open Diab Res Care. 2023;11(5):e003666. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003666

- 15.Diabetes – type 2: SGLT-2 inhibitors. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. December 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/diabetes-type-2/prescribing-information/sglt-2-inhibitors/

- 16.Heart failure – chronic: SGLT-2 Inhibitors. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. August 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/heart-failure-chronic/prescribing-information/sglt-2-inhibitors/

- 17.S. Padda I, U. Mahtani A, Parmar M. Sodium-Glucose Transport Protein 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576405/

- 18.Canagliflozin. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2024. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/canagliflozin/

- 19.Ueda P, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and risk of serious adverse events: nationwide register based cohort study. BMJ. Published online November 14, 2018:k4365. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4365

- 20.Beba H, Mills J. Diabetic ketoacidosis in adults: identification, diagnosis and management. The Pharmaceutical Journal. June 11, 2024. https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/diabetic-ketoacidosis-in-adults-identification-diagnosis-and-management