Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the acute complications of diabetes in adults;

- Support people living with diabetes to minimise their risk of developing acute risk complications;

- Provide advice or signpost people who may be experiencing an acute complication of diabetes appropriately for timely management or treatment.

More than 5.3 million people are currently living with diabetes in the UK. Of these, around 4.3 million people will have been formally diagnosed, with a further 850,000 people living with the condition but who are yet to be diagnosed[1]. The NHS spends 10% of its entire budget — around £10bn per year — on diabetes, with 80% of this spent on treating complications related to diabetes[2].

Acute complications of diabetes include diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state (HHS) and hyperglycaemia. These complications can be fatal if not diagnosed early and managed appropriately[3].

DKA is normally seen in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), with around 4% of patients experiencing DKA each year, equating to around 8.0–51.3 cases per 1,000 people with T1DM[4,5]. People with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) may also experience DKA, especially if they have ketosis-prone diabetes or have not stopped their sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) during periods of illness; however, this is less common[5]. DKA will not be covered in this article, as this has been previously covered in ‘Diabetic ketoacidosis in adults: identification, diagnosis and management’.

Diabetes places a significant burden on both the individual and wider society. Pharmacists working in all sectors are increasingly likely to encounter people living with diabetes who are at high risk of developing, or are currently experiencing, an acute complication. Pharmacists therefore need to be aware of the signs, symptoms and the management of the acute complication of diabetes to ensure patients receive appropriate advice and/or treatment.

This article will cover the acute complications of diabetes: hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia and HHS, and how to manage sick days in both T1DM and T2DM.

Hypoglycaemia

A common complication, people with T1DM experience around two episodes of mild hypoglycaemia each week.

Hypoglycaemia occurs when the level of blood glucose falls below 3.9mmol/L and results from an imbalance between glucose supply, glucose utilisation and existing insulin levels[6].

The American Diabetes Association recognises three levels of hypoglycaemia:

- Level 1: Glucose level: <3.9mmol/L

- Level 2: Glucose level: <3.0mmol/L

- Level 3: A severe event characterised by altered mental and/or physical status (rather than a measurable glucose number) requiring assistance for treatment[7].

Risk factors

A range of factors, including medical and lifestyle issues, and reduced carbohydrate intake or absorption, can contribute to hypoglycaemic episodes (see Table 1). For example, hypoglycaemia is the most common side effect of insulin, sulfonylurea and meglitinide therapy[8]. People with T2DM who are on insulin treatment are more likely to be admitted to hospital with severe hypoglycaemia compared with those who have T1DM[6].

Symptoms

Although the symptoms of hypoglycaemia can vary considerably between individuals, there are three main categories (see Table 2)[6]. Autonomic symptoms usually occur first and act as a prompt to the individual to take action to treat the hypoglycaemia. Neuroglycopenic symptoms result from the brain’s deprivation of glucose during hypoglycaemia, which can lead to confusion, tiredness or drowsiness, and more generalised symptoms can occur in some older people[9].

Consequences of hypoglycaemia include:

- Neurological:

- Seizures

- Coma

- Cognitive dysfunction

- Cardiovascular:

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Ischaemic heart disease

- Poor concordance with treatment;

- Accidents and injury;

- Psychological:

- Fear of hypoglycaemia

- Diabetes distress

- Reduced quality of life;

- Economic costs[10,11].

Repeated episodes of hypoglycaemia can also impair the counter-regulatory system’s response to falling glucose levels, potentially leading to the development of impaired hypoglycaemia awareness (IAH), which is the reduced ability to recognise the onset of acute hypoglycaemia and often means symptoms of hypoglycaemia are not triggered until glucose levels are very low[12,13]. IAH effects around 20–25% of people with T1DM and 10% of people with T2DM treated with insulin therapy[13].

Management

Immediate treatment is required when symptoms of hypoglycaemia arise. If the person is able to swallow, they should eat or drink around 15–20g of quick-acting carbohydrates; for example:

- 200mL of orange juice (not sugar free);

- 150mL full-sugar cola;

- 60mL glucojuice;

- Five glucose tablets;

- Six dextrose tablets;

- Five large jelly babies or seven small jelly babies;

- Three or four heaped teaspoonfuls of sugar added to a cup of water;

- Two tubes of glucose 40% gel[14].

If necessary, repeat treatment after 15 minutes, up to a maximum of three treatments in total, if blood glucose levels remain less than 4mmol/L or if the person still does not feel well. Once the hypoglycaemia has been successfully treated, and it is not mealtime yet, they should also be advised to eat some starchy foods, such as two plain biscuits, a small banana or one slice of toast[15].

In severe hypoglycaemia (requiring third party assistance), if the patient is unconscious:

- Call 999 and seek urgent medical assistance;

- If the patient is breathing, place them in the recovery position;

- If the patient is not breathing, commence cardiopulmonary resuscitation;

- 1mg of glucagon can be injected by a trained person;

- Once the individual is conscious and able to eat, they should be given a larger portion of long-acting carbohydrates to replenish glycogen stores (e.g. four biscuits, two slices of bread, or 400–600mL of milk) or a normal carbohydrate-containing meal, if due[15].

Prevention

Pharmacists can recommend actions that can be taken by people with diabetes to prevent episodes of hypoglycaemia; these include:

- Encouraging people with diabetes on a sulfonylurea and/or insulin therapy to know the early symptoms of hypoglycaemia and how to treat it promptly;

- Educating a person with diabetes on insulin therapy to be able to self-titrate and adjust timing of their insulin doses based on glucose levels, especially after increased physical activity, missed meals, or eating foods that can cause postmeal hyperglycaemia;

- Providing advice on ensuring sensible intake of alcohol (see ‘How to provide advice on alcohol consumption and explain the potential health risks’ for more information);

- Providing guidance on good injection technique and injection site rotation;

- Reminding the person with diabetes to have easy access to appropriate hypoglycaemia treatment, even when away from home and when driving;

- Encouraging people with diabetes to have meals and include a small portion of starchy carbohydrate with each meal (e.g. potatoes, rice, pasta, bread or cereals);

- Ensuring patients are having an annual diabetes review, and a HbA1c check at least every six months, if HbA1c is at target. More information can be found in ‘How to conduct a clinical review of a patient’s medicines’[14–20].

Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state

Previously called hyperosmolar non-ketotic diabetic coma, hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS) is a medical emergency and early diagnosis and management is vital. HHS is caused by a complete or relative lack of insulin and requires emergency hospital admission[21].

It is a condition that affects only people with T2DM owing to poorly treated T2DM or delayed diagnosis[21]. Although it occurs 7 times less frequently than DKA, it is associated with a mortality rate of 5–20%, which is 10 times higher than that reported for DKA[22].

Symptoms and risk factors

Infection or cardiovascular events are the most common predisposing factors for HHS. Patients affected are usually frail, severely dehydrated and clinically very unwell, with an altered level of consciousness, ranging from lethargy and confusion, to coma. Strict differentiation between HHS and DKA is often difficult as some patients with HHS may present with ketonuria. The onset of symptoms with HHS is slow, whereas symptoms of DKA occur rapidly, and the presenting blood glucose readings are often the key indicator as values with HHS can be 30–40 mmol/L or more (see ‘Diabetic ketoacidosis in adults: identification, diagnosis and management’ for further information)[23].

Common symptoms include:

- Increased urination;

- Increased thirst;

- Nausea;

- Dry skin;

- Disorientation and, in later stages, drowsiness and a gradual loss of consciousness[23].

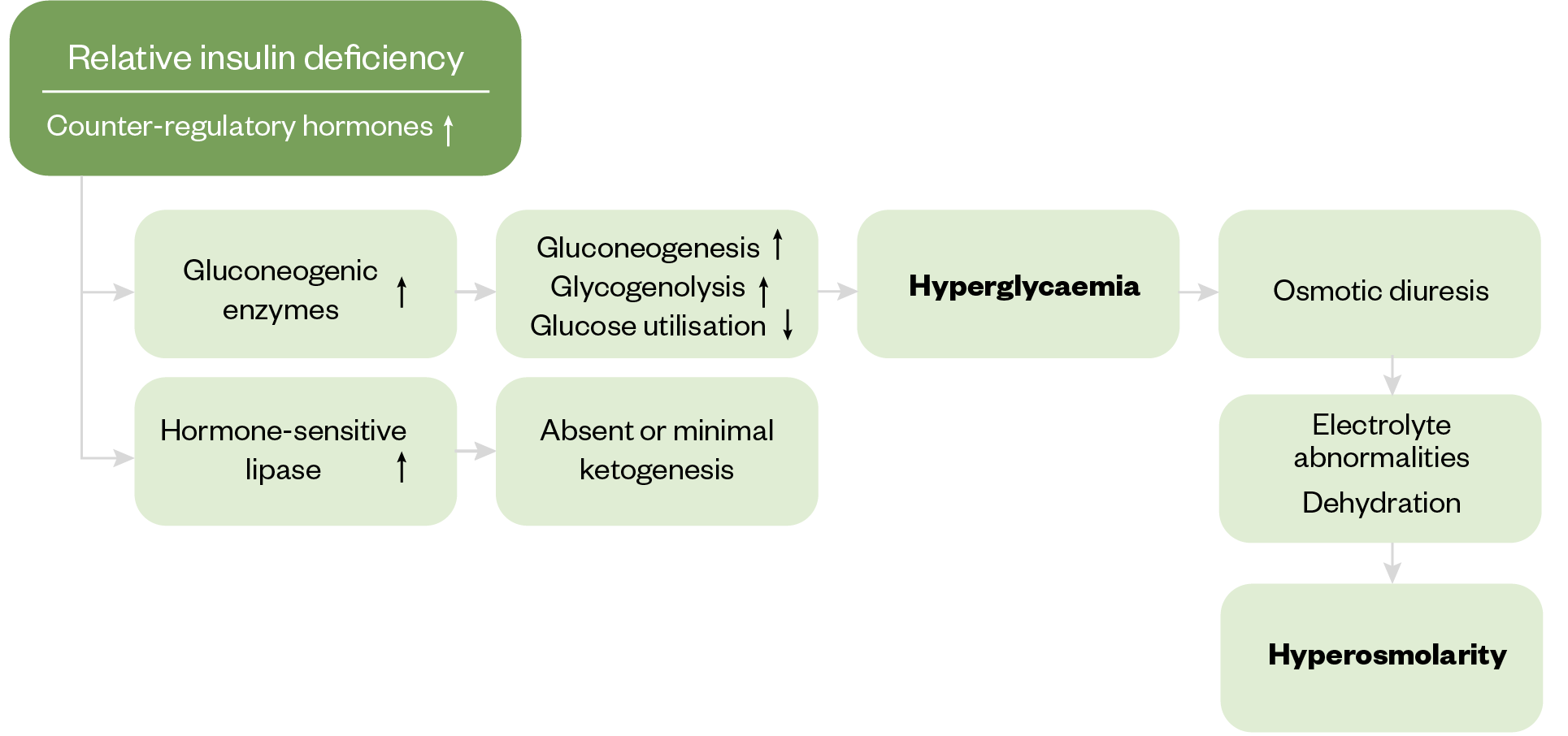

Owing to the deficiency of insulin, there is a decrease in glucose utilisation by the peripheral tissue, causing hyperglycaemia. Counter-regulatory hormones, including glucagon, growth hormone, cortisol and catecholamines are also released, stimulating gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, causing blood glucose levels to be raised even higher[21]. The pathophysiological changes that give rise to the symptoms of HHS are outlined in Figure 1[21].

Severe hyperglycaemia results in a rise in plasma osmolality in the extracellular fluid, which causes a shift of water from the intracellular to the extracellular space. Free water with electrolytes and glucose is lost via urinary excretion, producing glycosuria, which causes moderate to severe dehydration. Dehydration is usually more severe in HHS compared to DKA, and there is increased risk for cardiovascular collapse[21].

As a result of insulin deficiency, there is increased lipolysis, which causes an increased release of fatty acid as an alternative energy substrate for the peripheral tissues. In HHS, however, because insulin is still being produced by the beta cells in the pancreas, the generation of ketone bodies is minimal as insulin inhibits ketogenesis[24]. However, if ketone concentrations are high, the local DKA protocol may be appropriate[21].

International guidelines vary as to the precise definition of HHS, but there are characteristic features that differentiate it from other hyperglycaemic states such as DKA. These are summarised in Figure 2.

(<3.0mmol/L)

Management

The goals for treatment of HHS are to address the underlying cause(s) and to gradually and safely:

- Normalise the osmolality;

- Replace fluid and electrolyte losses;

- Normalise blood glucose.

Other management goals include the prevention of:

- Arterial or venous thrombosis;

- Other potential complications (e.g. cerebral oedema, central pontine myelinolysis and osmotic demyelination syndrome);

- Foot ulceration[22,25–27].

Hyperglycaemia

High levels of blood glucose, or hyperglycaemia, occur when levels are above 7mmol/L before a meal and above 8.5mmol/L two hours after a meal[28].

Symptoms and risk factors

Common causes for hyperglycaemia include:

- Poor compliance or under treatment with glucose-lowering medication;

- Excess intake of carbohydrates (>130g/day);

- Stress;

- Infection;

- Over-treatment of hypoglycaemia[28,29].

Symptoms of high blood glucose usually develop gradually and may only start when blood glucose levels become very high. These include:

- Polyuria, especially nocturnal;

- Polydipsia;

- Tiredness and lethargy;

- Thrush or other recurring bladder and skin infections;

- Headaches;

- Blurred vision;

- Weight loss;

- Feeling sick[28].

Prolonged hyperglycaemia can increase the risk of diabetes-related complications, including microvascular complications (e.g. retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy), macrovascular complications (e.g. cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral arterial disease), and metabolic complications (e.g. dyslipidaemia and DKA)[28].

Prevention

Hyperglycaemia can be prevented by: compliance with glucose-lowering medication; awareness of hyperglycaemia symptoms; dietary awareness, such as carbohydrate counting; avoiding high-glycaemic-index foods; increasing fibre; managing stress; doing regular exercise; losing weight; and following “sick day rules” appropriately (see Box)[29].

Management

Hyperglycaemia can be managed by seeking advice from a diabetes specialist team when experiencing symptoms of hyperglycaemia; self-increasing the dose of insulin if the patient has knowledge on how to do this safely; amending diet to reduce carbohydrate intake (if intake >130g daily); and increasing compliance of glucose-lowering drugs if not taken regularly.

Box: Sick-day rules

During periods of illness, patients with diabetes should be advised to:

- Keep hydrated (drink at least 100mL water every hour);

- Maintain carbohydrate intake (meals can be replaced with sugary drinks or ice cream);

- Continue taking insulin if prescribed and adjust insulin doses if needed (see TREND illness in type 1 diabetes and TREND illness in type 2 diabetes for more information);

- Stop some medicines, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers, SGLT2i, metformin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and diuretics, to prevent acute kidney injury (see sick-day rule cards);

- Seek medical attention if glucose levels are persistently above 18mmol/L or if they are unable to stay hydrated owing to vomiting;

- Stop sulfonylureas (if prescribed) if they are not eating or drinking to prevent hypoglycaemia;

- Stop glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (if prescribed) if there is a risk of dehydration owing to continuous vomiting and/or diarrhoea, or reduction of fluid intake;

- Monitor their glucose levels if they have access to continuous glucose monitoring/flash device or record glucose levels using a blood glucomes monitor at least four times daily;

- Look out for symptoms of hyperglycaemia, including thirst, passing more urine than usual and tiredness[30–32].

Best practice for pharmacists and pharmacy professionals

- Ensure that you can recognise the signs, symptoms and risk factors of acute complications in diabetes, so that people living with diabetes who are at risk of these can receive appropriate advice or timely treatment;

- Counsel patients on insulin and/or sulfonylureas on the symptoms and treatment of hypoglycaemia, including during an annual diabetes review;

- Counsel patients who do not have access to a blood glucose meter on the symptoms and treatment of hyperglycaemia;

- Ensure people on insulin and/or sulfonylureas have access to glucose monitoring (people with T1DM should have access to a dual blood/ketone monitoring meter);

- Educate people living with diabetes on sick day rules and awareness of which glucose-lowering medicine should be stopped temporarily during periods of illness;

- Encourage people living with diabetes to seek advice from their diabetes specialist team when needed;

- Support people living with diabetes to become empowered in managing their diabetes appropriately and thereby reducing the risk of acute complications of diabetes.

- 1How many people in the UK have diabetes? Diabetes UK. 2022. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/about-us/about-the-charity/our-strategy/statistics?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAy9msBhD0ARIsANbk0A9FEYB3fRSz-QK8LoWFmA3aM_UETPZJutvoqyIvld4ynBnwT0sNoMkaAmQWEALw_wcB (accessed April 2024)

- 2Whicher CA, O’Neill S, Holt RIG. Diabetes in the UK: 2019. Diabet. Med. 2020;37:242–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14225

- 3Negera GZ, Weldegebriel B, Fekadu G. <p>Acute Complications of Diabetes and its Predictors among Adult Diabetic Patients at Jimma Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia</p> DMSO. 2020;Volume 13:1237–42. https://doi.org/10.2147/dmso.s249163

- 4Misra S, Oliver NS. Diabetic ketoacidosis in adults. BMJ. 2015;h5660. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h5660

- 5Diabetic ketoacidosis in adults: identification, diagnosis and management. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2022.1.129204

- 6The hospital management of hypoglycaemia in adults with diabetes mellitus. Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care . 2023. https://abcd.care/sites/default/files/site_uploads/JBDS_Guidelines_Current/JBDS_01_Hypo_Guideline_with_QR_code_January_2023.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 76. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2021;45:S83–96. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-s006

- 8Nakhleh A, Shehadeh N. Hypoglycemia in diabetes: An update on pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention. WJD. 2021;12:2036–49. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v12.i12.2036

- 9Tesfaye N, Seaquist ER. Neuroendocrine responses to hypoglycemia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1212:12–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05820.x

- 10Amiel SA. The consequences of hypoglycaemia. Diabetologia. 2021;64:963–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05366-3

- 11Milne N. How to prevent, identify and manage hypoglycaemia in adults with diabetes. Diabetes & Primary Care . 2022. https://diabetesonthenet.com/wp-content/uploads/DPC_24-3_69-70.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 12Kalra S, Mukherjee J, Venkataraman S, et al. Hypoglycemia: The neglected complication. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2013;17:819. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.117219

- 13McNeilly AD, McCrimmon RJ. Impaired hypoglycaemia awareness in type 1 diabetes: lessons from the lab. Diabetologia. 2018;61:743–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-018-4548-8

- 14Hypoglycaemia. British National Formulary. 2024. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/hypoglycaemia/ (accessed April 2024)

- 15Hypoglycaemia in adults in the community: recognition, management and prevention. Trend Diabetes. 2023. https://trenddiabetes.online/portfolio/hypoglycaemia-in-adults-in-the-community-recognition-management-and-prevention/ (accessed April 2024)

- 16Managing mealtime insulin. Trend Diabetes. 2018. https://www.mydiabetes.com/media/1161/a5_mealtime_trend_final.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 17Diabetes: Insulin Initiation and Adjustment, Patients with Type 2 Primary Care: Guidance for Diabetes Specialist Nurses. NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. 2023. https://rightdecisions.scot.nhs.uk/media/2731/148-diabetes-insulin-initiation-amended.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 18FIT Recommendations. Fit4Diabetes. 2023. https://fit4diabetes.com/fit-recommendations/ (accessed April 2024)

- 19Type 2 diabetes in adults: management . National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28/resources/type-2-diabetes-in-adults-management-pdf-1837338615493 (accessed April 2024)

- 20Karslioglu French E, Donihi AC, Korytkowski MT. Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome: review of acute decompensated diabetes in adult patients. BMJ. 2019;l1114. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1114

- 21The management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS) in adults. Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care. 2022. https://abcd.care/sites/default/files/site_uploads/JBDS_Guidelines_Current/JBDS_06_The_Management_of_Hyperosmolar_Hyperglycaemic_State_HHS_%20in_Adults_FINAL_0.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 22Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state . Diabetes UK. 2024. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/complications/hyperosmolar_hyperglycaemic_state_hhs (accessed April 2024)

- 23Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome . National Library of Medicine. 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482142/ (accessed April 2024)

- 24Varela D, Held N, Linas S. Overview of Cerebral Edema During Correction of Hyperglycemic Crises. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:562–6. https://doi.org/10.12659/ajcr.908465

- 25Hegazi MO, Mashankar A. Central Pontine Myelinolysis in the Hyperosmolar Hyperglycaemic State. Med Princ Pract. 2012;22:96–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000341718

- 26Jain E, Kotwal S, Gnanaraj J, et al. Osmotic Demyelination After Rapid Correction of Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemia. Cureus. 2023. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.34551

- 27Hyperglycaemia (hyper). Diabetes UK. 2023. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/complications/hypers (accessed April 2024)

- 28High blood sugar (hyperglycaemia). NHS. 2022. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/high-blood-sugar-hyperglycaemia/ (accessed April 2024)

- 29Primary Care Sick Day Guidance for the management of adult patients with diabetes mellitus. Birmingham, Solihull, Sandwell and Environs Area Prescribing Committee. 2020. https://www.birminghamandsurroundsformulary.nhs.uk/docs/ACG/Primary%20Care%20Sick%20Day%20Information%20for%20Adult%20patients%20with%20diabetes.pdf?uid=310747648&uid2=20213189313357 (accessed April 2024)

- 30Type 1 diabetes: what to do when you are ill . Trend Diabetes. 2020. http://www.trenddiabetes.online/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/A5_T1Illness_TREND_FINAL.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 31Type 2 diabetes: what to do when you are ill. Trend Diabetes. 2020. http://www.trenddiabetes.online/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/A5_T2Illness_TREND_FINAL.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 32Down S. How to advise on sick day rules. Diabetes & Primary Care . 2020. https://diabetesonthenet.com/wp-content/uploads/pdf/dotn024ae8fb1b78500b7bc752b98e9b6d92.pdf (accessed April 2024)