This content was published in 2002. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Identify gaps in your knowledge

- What are the two key elements for giving an effective presentation?

- List three attention grabbing techniques.

- What kind of signs indicate that an audience member might be confused?

This article could relate to the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s core competencies of “management”, “health promotion” and “staff training” (see “Medicines, ethics and practice — a guide for pharmacists”, number 26, July 2002). You should consider how it will be of value to your practice.

According to author Suzy Siddons: “A good presentation contains many of the same constituents as a good restaurant meal. The participants should be hungry. The chef should be at least competent, if not inspired. The menu should be tempting, understandable and offer a range of choices to all the diners. The ingredients should be the best possible.”1 And she’s right. The thing that whets your appetite the most for a meal is the first impression. Even if a meal surprises you because it tastes better than it looks, your mood for the meal is set from the moment you see it.

The same is true of presentations. Try to think of the best presentation you have ever heard. You probably knew you were going to enjoy the presentation within the first few moments, when the speaker opened “with a bang” or said or did something to raise your curiosity about what was to follow. Good, memorable presentations do not happen by accident. They are carefully planned and competently delivered. In this article I will focus on the two key elements for giving effective presentations: preparation and delivery.

PREPARATION

What you say

Like any other form of communication, in order for a presentation to be effective you have to consider your audience and you have to think of structure. Think about other forms of communication such as newspaper articles or radio programmes. Your interest in reading or listening is aroused by the introduction. The body of the story contains the detail and at the end, there should be some kind of summary. For any presentation to be successful the same rules apply — it must have an introduction, a body and a conclusion.

But before you even think about how to structure a presentation you have to know why it is being given in the first place. If you have been invited to give an after dinner presentation then it is most likely that you will be expected to entertain the audience. For most other types of presentation your audience will expect to be instructed, persuaded, inspired or motivated and you need to have a strategy for meeting these expectations.

Who are your audience?

Knowing your audience is fundamental to pitching your presentation at the right level. For example, will the audience be experts in a particular field, a mixture of health care professionals or a group of pregnant women? It is impossible for a presentation to meet the needs of all, so the safest option is to aim for the middle. It might also be prudent to check with the organisers on any audience history. For example, have members of the audience had negative experiences with the organisation that you represent in the past? Being aware that your audience might be predisposed to negative feelings can help you to tailor your presentation to take account of previous difficulties or at least to be prepared for a hostile audience, eg, by anticipating divisive questions. If you do encounter a difficult audience, always try to remain friendly and calm.

Preparing your subject matter

Having identified the purpose of your presentation and armed with knowledge about your audience, you can start to prepare your information. Gather information that you know will be relevant to the needs of your audience and their level of expertise and experience. Sort your information into a logical order much as you would do if you were writing an essay. Become familiar with the subject not just by reading about it but by thinking it through.

The more you know your subject, the better your presentation. However being an expert in a subject can be a disadvantage. According to the authors of ‘Powerful presentations — great ideas for making a real impact’2: “The most dangerous subject in the world is the subject where you are the great expert or enthusiast. You can so easily drone on about it, regardless of your audience, for your own interest or pleasure”. Be conscious of directing your presentation to the audience and as you prepare your material, think “you”, “your” and “yours” rather than “me”, “my” and “mine” to avoid falling into the trap of concentrating too much on your personal experience.

Having organised your material into logical groups, you can then start to think about “route mapping”. As mentioned before, presentations have a clear purpose. They have to take audiences on a journey that leads somewhere and that final destination has to be mapped. There are various ways of getting to that final destination and you have to decide which is best. For example:

- Chronological approach: outline what has happened with time (eg, state the origin and development of a drug)

- Theory-practice approach: outline the theory (eg, new legislation) then discuss the impact and implications of the theory

- Problem-solution approach: outline details of a problem (eg, dispensing errors) then discuss solutions

- Cause-effect approach: discuss practical consequences of different types of action (eg, choosing between providing a local pharmaceutical service and not providing one)

- Simple-complex approach: use building blocks to talk about complex processes

- Compare-contrast approach: apply the same model to different events (eg, ask what the clinical and cost benefits are of using drug A or drug B)

You can use alternative formats or even choose to combine aspects of different approaches, but whichever option you choose, it needs to be logical.

The introduction

Once you have worked out the structure and body of your presentation, you can start to think about how to introduce it. Because first impressions count, your introduction must not only open your presentation effectively but it must also grab and hold the audience’s attention. If you lose your audience in the first five minutes, you have lost them for the rest of the presentation. You can grab your audience’s attention by using any of the following techniques:

- Question: open with a direct question to the audience, eg, “How do you feel about online pharmacies?”

- Quote: use a quote or proverb such as “Evil people prosper because good people let them”

- Anecdote: tell a story about a particular character. This technique will engage your audience and get them to visualise anduse their imaginations to fill in the gaps

- Shock openings: open with something that will shock your audience into alertness, eg,“Every day 10 million people in Britain phone their employers and pretend to be sick”

Having captured your audience’s attention you can then continue to introduce your subject. At this point, it helps if you remind them how long you intend to speak for and whether you are prepared to take questions throughout or at the end of your presentation. Outline the structure of your presentation. Basically, tell them what to expect.

The conclusion

Your conclusion should be as strong as your introduction because the last words you say are the words most likely to be remembered. Your conclusion should relate to the theme of your presentation and should follow on logically from what was previously said. It should also link to your purpose for giving the presentation. If for example the presentation was designed to persuade, then you need to tell the audience what steps they need to take next. Likewise, if the presentation was designed to motivate, the audience should be clear about the actions they can take if they feel motivated. Your last sentences should sound final and should not leave your audience “up in the air”. Keep them short, succinct and conclusive.

Audio-visual aids

Use audio-visual aids to complement your presentation but not to replace it. If your presentation contains many figures, statistics and comparisons then perhaps audio-visual aids will help. Examples of aids you can choose from include overhead projector, 35mm slides, videos and film, computer projection (eg, Powerpoint), flip chart or white board, real objects (passed around the audience) and posters. In choosing audio-visual aids, considerwhether or not your audience is going to be taking notes.

Relax

A vital piece of preparation needed before delivering your presentation is to relax. Practise relaxation techniques and breathing exercises to calm your nerves. Look at ideas for relaxing before giving a presentation in ‘Speak for yourself’.3

DELIVERY

How you say it

The best presentations are ones that are unscripted and sound like the speaker is talking directly to you. You might be tempted to keep a script with you “just in case” but this is restrictive. Imagine what would happen if you suddenly missed a line in the script. Reading from a script also limits your ability to make contact with your audience.

Again the key is knowing your subject. If you have prepared thoroughly, you will only need cue or note cards to guide you through your presentation. This kind of delivery is known as extemporaneous and is based on key points or ideas written on cards as the basis of a presentation rather than a script. This allows you to talk freely and make contact with your audience. An extemporaneous presentation is also a more flexible form of delivery because you have ideas rather than words fixed in your mind. So, for example, if on the day of your presentation, you see that your audience is much younger than you imagined, you will be able to tailor your presentation to suit them.

Unlike the written word, a presentation does not allow the audience the space or time to go back and check on that one phrase they did not quite understand. Therefore your presentation needs to be unambiguous, clear and coherent. “The spoken word exists only for the moment. It must be instantly intelligible”.4 You can help your audience by using signposts. Tell them what is coming, where it leads to or why it is significant. Do not just deliver dry information but outline benefits, effects, implications, advantages, disadvantages and so on. Appeal to your audience’s emotions so that they become involved in the presentation and can see that the content of the presentation is personally relevant to them.

Rehearse

Practice is vital. Try to rehearse your delivery beforehand if only to get used to the sound of your own voice and also to practise projecting your voice. If you will be speaking without a microphone, you need to be sure that your voice will project to the back row of your audience. Rehearsal allows you to check your timing and make sure your presentation is of an appropriate length for the time allocated. It also gives you the important chance to rehearse the words that are most effective in enabling you to convey your thoughts and ideas. Use words that are natural to you. If you can find a willing relative or friend, practise your presentation in front of them and ask for feedback. Alternatively, video record your presentation and check for the following:

- Fluency: is your delivery fluent? Does it flow clearly or are there too many pauses?

- Varied speech: do you use pauses effectively to punctuate your presentation, change from one idea to another to emphasise a point or allow your audience to answer a rhetorical question? Do you vary the pitch of your voice by stressing particular words to convey the importance of an idea or thought? Is the tone of your voice varied? Is your vocabulary varied?

- Pace: do you speak too quickly, in a rush to end the “ordeal”

- Enthusiasm: does your presentation sound sufficiently enthusiastic? If you do not feel enthusiastic about your own presentation, do not expect your audience to feel enthusiastic

- Body language: are you glued to the spot or do you move? Do you move your arms to gesture? Body language is an entire subject in itself

During the rehearsal stage you will also need to look at practical issues such as the seating arrangements in the room, whether a microphone will be available, audio-visual facilities and so on.

During the presentation

A good speaker is able to read his or her audience (to gauge whether or not he or she is communicating clearly) and fine tune the presentation accordingly. If an audience member is confused he or she may give non-verbal signs which could include tilting the head, lowering the eyebrows, squinting the eyes, crossing arms and legs, turning away from you and avoiding eye contact. You can use such signs as a cue for you to spend longer explaining a concept.

DEALING WITH QUESTIONS

Having to deal with questions is probably the part of giving presentations that people dread most. However, time for questions is an opportunity for you to make sure that you get your message across. Try to think of the 10 questions you are most likely to be asked and plan your answers. If you rehearse your presentation in front of friends, they could supply the questions. When asked a question, compliment the person who has asked it (eg, “That’s a good question”). Make sure you understand the question being asked, for example paraphrase the question back to the questioner. This also gives you time to think about your answer. For large audiences, ask the questioner to stand up and state his or her name and organisation for background information.

In answering a question, make sure you do not digress. If you do not know the answer, offer to get back to the person with the answerat a later date. If questions are slow coming in, you could play devil’s advocate by posing a question to the audience. If you can, use the last question to summarise your presentation.

SUMMARY

Nobody is born a perfect speaker. Do not forget that you make presentations every day, albeit on a one-to-one basis. For example, you might use presentation skills in counselling a patient, training a member of staff or answering a query from another health care professional. Public speaking is a skill that can be acquired and with practice your skill and confidence will increase. You may even find yourself enjoying it. Panel 1 gives some more presentation tips.

Panel 1: Tips for giving presentations

- Make sure that you can sum up the purpose of your presentation in one concise sentence

- If possible, take the time to greet and chat to some of your audience as they arrive. This will mean that you are not talking to complete strangers

- Number your cue cards in case you drop them

- Look at the audience as much as possible. If you use visual aids, make sure you do not end up talking to the projector or the screen. And make sure you are not blocking the audience’s view

- Get to the venue early and familiarise yourself with the room. For example, are there any loose cables leading from equipment? Make sure you know how to work the equipment before your presentation

- If you use overhead projector transparencies or slides, choose your colours carefully. Orange and yellow do not show up well

- Silences may seem long to you, but will seem less so to your audience

- Make sure you have a glass of water on hand

- Do not attempt to make jokes unless you can do so naturally

- Do not worry about feeling anxious. Even experienced speakers feel some anxiety when making presentations — it is normal

Action: practice points

- Next time you demonstrate the use of an inhaler to a patient, ask a member of staff to judge your delivery skills in terms of fluency, tone, body language etc.

- There is no substitute for practice. Give a presentation about effective presentations to a small group of colleagues. Then ask for feedback. For example, colleagues could be asked to comment on or rate the extent to which your introduction captured their interest, the clarity of your presentation structure, the relevance of your material, whether or not visual aids were used effectively, whether or not you reinforced the key points in your conclusion, how well you delivered the presentation, how well you handled questions etc.

- Next time you go to a presentation, evaluate how effective it was and identify the skills and weaknesses of the presenter. In what ways could the presentation have been improved?

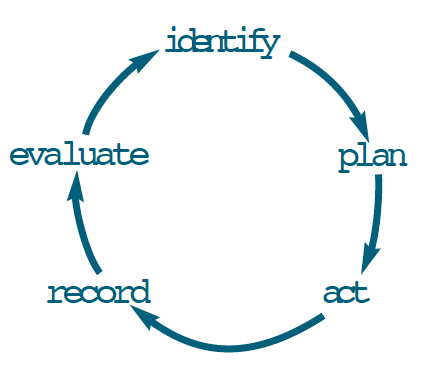

Evaluate

How could your learning have been more effective? What will you do now and how will this be achieved?

References

- Siddons S. Presentation skills. 2nd ed. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development; 1999.

- Ehronbog J, Mattock, J. Powerful presentations — great ideas for making a real impact. 3rd ed. London: Kogan Page; 2001

- Stuart C. Speak for yourself — the complete guide to effective communication and powerful presentations. London: Piatkus; 2000.

- Yoder, E. Essential presentation skills. Hampshire: Gower;1996.