Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Identify the steps required to design and implement effective health education interventions in primary care pharmacy settings;

- Apply the ‘Making every contact count’ (MECC) framework to deliver health promotion consultations at different levels of the MECC pyramid;

- Map behaviour change interventions to the national guidelines to ensure evidence-based practice;

- Develop strategies to overcome challenges in delivering health education interventions in pharmacy settings, focusing on improving their impact on public health outcomes.

Introduction

Pharmacists and pharmacy teams working across primary care, including community pharmacies, have an important role in the healthcare system, not only as dispensers of medications but also as providers of health education1. With their unique position in communities, pharmacies are accessible and often the first point of contact for patients seeking healthcare advice. As registered and trusted healthcare professionals, pharmacists possess the expertise and accessibility to educate individuals about managing their health, improving their wellbeing and making informed decisions2,3.

Health education interventions are aimed to improve health status, educate people about health issues, create self-awareness, alter unhealthy behaviours and encourage positive change4. Health education interventions in pharmacy settings are essential in addressing the increasing demand for preventative care and promoting healthier lifestyles5. By empowering individuals with the knowledge and resources needed to make positive changes — such as smoking cessation, weight management and vaccinations6 — pharmacists contribute to improving public health outcomes and reducing the burden on healthcare services7.

Examples of how pharmacists can build public health literacy and improve patients’ ability to understand and manage their health through education can be found in ‘Smoking cessation services: how nicotine replacement therapy and counselling through pharmacy can support adherence and quitting’, published by The Pharmaceutical Journal in September 2023.

Brief and impactful interactions foster a culture of proactive health management, where patients are encouraged to take ownership of their health, seek timely interventions and adopt healthier behaviours. Proactive health management is particularly important in the context of rising rates of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and respiratory conditions, which can be managed and even prevented through education and behaviour change.

This article discusses the frameworks that are available to support the identification, design and delivery of health education interventions in primary care.

Frameworks that support engagement

To effectively deliver health education in primary care pharmacy settings, pharmacists and pharmacy teams can use established frameworks, such as the ‘Making every contact count’ (MECC) approach guideline and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) ‘Behaviour change: individual approaches’ guideline8,9. These frameworks provide structured approaches to help pharmacy teams engage patients, deliver consistent messages and tailor interventions to individual needs.

‘Making every contact count’ framework

The MECC framework empowers healthcare professionals to promote health and wellbeing during routine interactions, such as medicines consultations or dispensing visits. MECC focuses on delivering brief, non-judgemental and supportive conversations to raise awareness and provide simple health messages, as well as signpost patients to appropriate services8.

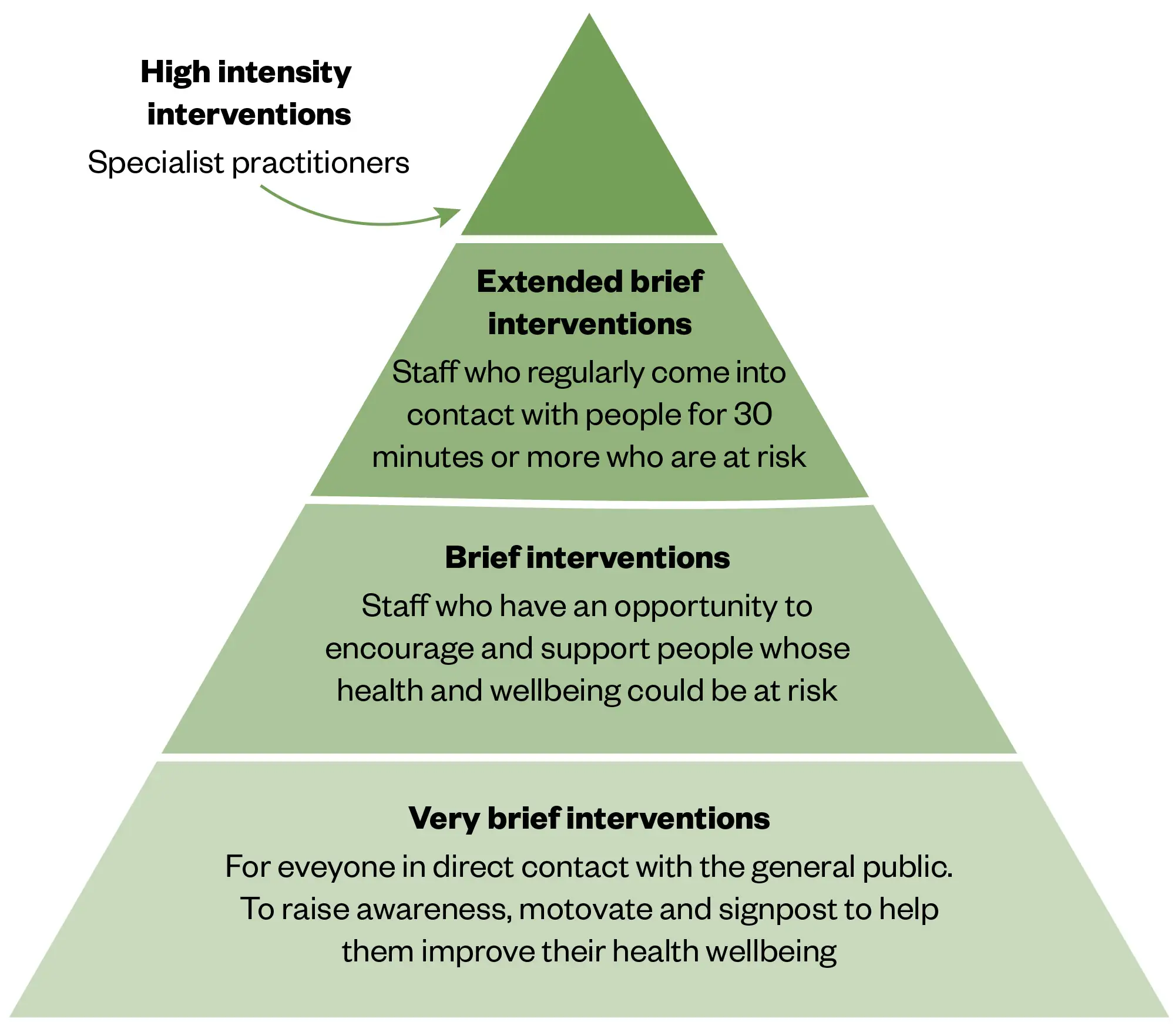

By incorporating these interventions at every opportunity, pharmacy teams can influence patient behaviour, encourage healthier choices and motivate individuals to seek additional support. MECC operates at varying levels, from basic signposting and brief advice to more intensive behaviour change interventions for those needing greater support (see Figure 110).

The Pharmaceutical Journal

‘Behaviour change: individual approaches’ guideline

The NICE guideline focuses on behaviour change and provides evidence-based recommendations for delivering individual interventions to improve health outcomes11. This framework is grounded in the COM-B model (capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour), which helps healthcare professionals understand the factors that influence behaviour and how to tailor interventions accordingly.

Pharmacists can apply these principles by assessing each patient’s specific needs, offering personalised support and motivating individuals to make sustainable changes. The NICE guideline recommends a range of techniques, which include goal-setting, self-monitoring, motivational interviewing and social support — all of which can be effectively utilised in the pharmacy setting.

To implement these strategies, pharmacists should follow a structured process. The following steps outline how to design, deliver and evaluate health education interventions within the pharmacy setting, which ensure that these efforts are impactful, sustainable and aligned with best practices (see Figure 2)11.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Step 1: Assessing the need for health education

Carrying out a thorough needs assessment can help to identify priority health concerns and ensure tailored interventions:

- Identifying health issues: Use local data (e.g. the prevalence of chronic conditions, such as hypertension or smoking) to identify education gaps, which can be accessed via NHS England Digital;

- Example: Local NHS stop smoking service data can provide insights into the demand and success rates of cessation programmes12.

- Engaging stakeholders: Consult patients, pharmacy staff and other healthcare professionals to pinpoint vital health education needs;

- Examples:

- Pharmacies in the UK surveyed patients about their health priorities and discovered a high interest in managing hypertension13;

- Pharmacist-managed diabetes programmes can help improve treatment adherence and patient outcomes14;

- Pharmacists were integrated into GP teams to manage long-term medical conditions yielding a number of benefits15.

- Examples:

- Defining SMART objectives: Goals such as “increasing smoking cessation attempts by 20% within six months” ensure focused efforts.

- Examples:

- SMART goal setting by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention16;

- SMART objectives by NHS Health Scotland17;

- The World Health Organization (WHO)’s guidance on target setting for health promotion18;

- Public Health England’s ‘Population health toolkit’.

- Examples:

Step 2: Designing health education interventions

Health education interventions are most effective when aligned with established frameworks like MECC and behaviour change models.

‘Making every contact count’ framework

MECC focuses on embedding brief health-promoting conversations into everyday interactions. Pharmacy teams can use these short engagements to raise awareness, motivate change and signpost services10.

Behaviour change and NICE recommendations

The NICE ‘Behaviour change: individual approaches’ guideline recommends:

- Assessing individual capability, opportunity and motivation to change (aligned with COM-B);

- Offering personalised interventions, such as brief advice, motivational interviewing and ongoing support11,19.

Selecting health topics

Interventions may target relevant public health issues, for example:

- Cardiovascular disease;

- Smoking;

- Sexual health, reproductive health and HIV;

- Healthy ageing;

- Mental health;

- Vaccination20.

An example of smoking cessation intervention carried out in a community pharmacy can be seen in Box 1.

Integrating the MECC pyramid

The MECC framework organises interventions into three levels:

- Signposting: Providing information and resources (e.g., leaflets and referral to services);

- Brief advice: Delivering concise, tailored advice during routine interactions;

- Behaviour change interventions: Offering structured support to individuals motivated to change11.

Box 1: Example: smoking cessation intervention in a community pharmacy

- Signposting:

- Description: Provide patients with accessible information and connect them to appropriate resources or services for tobacco cessation;

- Example:

- A pharmacy assistant hands out NHS leaflets on tobacco cessation to patients purchasing over-the-counter cold remedies;

- The assistant informs patients about local smoking cessation clinics and how to access them;

- Contact information for a free Quitline is prominently displayed at the pharmacy counter.

- Brief advice:

- Description: Deliver concise, tailored advice to encourage patients to take the first step toward quitting;

- Example:

- A pharmacist identifies a patient, who smokes, collecting a prescription for antihypertensives;

- During a routine medicines consultation, the pharmacist explains the impact of smoking on blood pressure and the benefits of quitting;

- The pharmacist advises trying nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and refers the patient to the pharmacy’s smoking cessation lead for further support.

- Behaviour change interventions:

- Description: Offer structured, personalised support for patients who are ready to quit smoking;

- Example:

- A pharmacy technician, trained as the smoking cessation lead, conducts one-on-one sessions with referred patients;

- The sessions involve creating a personalised quit plan, selecting appropriate NRT options and using motivational interviewing techniques to address barriers;

- The technician performs regular follow-ups, including carbon monoxide breath tests and progress tracking, to reinforce commitment and adjust the intervention as needed.

Step 3: Engaging and training pharmacy teams

Pharmacy teams play a central role in delivering health education and preparing them involves:

- Training on MECC and behaviour change techniques: Equip teams with the skills for effective communication, motivational interviewing and cultural competency. NHS England has the MECC e-learning programme, which is freely available to access without having to register, unless a certificate is needed21;

- Defining roles: Assign responsibilities for delivering brief advice, running workshops and managing follow-ups;

- Collaboration: Partner with general practitioners (GPs), nurses and public health officials to ensure a cohesive approach.

How pharmacy teams can best used and trained using the previous smoking cessation example can be seen in Box 2 and a suggested workflow in Box 3.

Box 2: Continuation of the example: smoking cessation intervention in a community pharmacy

- Pharmacist:

- Primary responsibility: Deliver brief advice during routine consultations;

- Tasks:

- Identify patients who smoke using patient records or routine questioning;

- Use MECC principles to provide two to three minutes of brief advice on tobacco cessation;

- Explain benefits of quitting and available support (e.g., nicotine replacement therapy and local smoking cessation services);

- Refer interested patients to the designated smoking cessation lead for follow-up.

- Smoking cessation lead (pharmacy technician):

- Primary responsibility: Manage follow-ups and run smoking cessation workshops;

- Tasks:

- Schedule one-on-one follow-up appointments for patients referred by the pharmacist;

- Organise weekly group workshops on tobacco cessation strategies;

- Monitor patient progress using CO breath tests and self-reported smoking diaries;

- Keep accurate records of outcomes for evaluation purposes.

- Pharmacy assistant:

- Primary responsibility: Support logistics and patient engagement;

- Tasks:

- Distribute educational leaflets on tobacco cessation at the pharmacy counter;

- Assist patients in signing up for workshops or follow-up appointments;

- Maintain supplies for cessation aids (e.g., nicotine patches and gum);

- Record patient interest in health education programmes for future outreach.

- Collaborating GP or nurse:

- Primary responsibility: Provide additional clinical support;

- Tasks:

- Manage referrals from the pharmacy for patients requiring prescription cessation aids;

- Conduct follow-up health checks (e.g. monitoring blood pressure and lung function);

- Communicate outcomes to the pharmacy team to ensure continuity of care.

- Manager/team leader:

- Primary responsibility: Oversee the programme and ensure adherence to best practices;

- Tasks:

- Develop and implement workflows for the intervention;

- Provide staff training on MECC and NICE guidelines10,11;

- Monitor programme effectiveness and report outcomes to stakeholders (e.g., local health authorities);

- Address any challenges or resource needs to maintain smooth operations.

Box 3: Implementation workflow example

- Pharmacist interaction:

- A patient collecting repeat medicines is identified as a smoker;

- The pharmacist spends two minutes delivering brief advice and refers the patient to the smoking cessation lead.

- Follow-up by technician:

- The technician schedules a workshop or one-on-one session within a week;

- Patients are provided with NRT options and practical guidance on quitting.

- Logistics and monitoring by assistant:

- The assistant ensures workshop materials and cessation aids are prepared;

- Follow-up appointments are scheduled for CO testing or check-ins.

- Collaborative care:

- Patients with comorbidities are referred to the GP;

- The GP provides clinical interventions, such as prescribing varenicline, and shares updates with the pharmacy team.

- Evaluation by team leader:

- Programme outcomes (e.g., quit rates and patient satisfaction) are reviewed quarterly;

- Adjustments to roles or processes are made based on feedback.

Step 4: Implementing the intervention

Effective implementation combines strategic planning, community outreach and resource management. Delivery methods include:

- In-pharmacy services: One-on-one counselling or workshops during non-peak hours;

- Community outreach: Extending services to local schools, workplaces or events;

- Digital tools: Using apps, videos and online consultations for remote access.

Promoting accessibility ensures patients from diverse backgrounds can benefit. For example:

- Offering multilingual resources;

- Scheduling flexible session timings;

- Removing cost barriers by leveraging public health funding.

An overview of how the previously discussed smoking cessation can be implemented can be seen in Box 4.

Box 4: Continuation of the example: smoking cessation intervention in a community pharmacy

- In-pharmacy services:

- Description: Deliver one-on-one counselling or group workshops to patients seeking help with smoking cessation;

- Examples:

- Conduct personalised quit-smoking consultations during non-peak pharmacy hours;

- Host weekly workshops on smoking cessation strategies, including managing cravings and using NRT.

- Community outreach

- Description: Extend smoking cessation services beyond the pharmacy to reach broader audiences;

- Examples:

- Partner with local schools to educate students on the dangers of tobacco use and offer smoking prevention workshops;

- Collaborate with workplaces to provide employees with lunchtime tobacco cessation sessions or informational seminars;

- Set up an information booth at community health fairs, offering carbon monoxide breath tests and promoting cessation services.

- Digital tools

- Description: Leverage technology to provide remote and on-demand support for quitting smoking;

- Examples:

- Recommend a trusted smoking cessation app that tracks progress and offers motivational messages;

- Use pharmacy-branded videos to demonstrate proper use of NRT products and share them via social media or email;

- Offer online consultations with the pharmacy’s smoking cessation lead for patients unable to visit in person.

- Promoting accessibility

- Multilingual resources: Provide patient leaflets and workshop materials in multiple languages to cater to the community’s diverse population;

- Flexible timings: Offer consultations and workshops outside typical working hours, such as evenings or weekends, to accommodate patients with busy schedules;

- Removing cost barriers: Utilise public health funding or NHS smoking cessation programmes to offer free or subsidised NRT and support services.

Step 5: Monitoring and evaluation

Regular evaluation ensures interventions meet their objectives and improve over time:

- Data collection: Use surveys, interviews and health metrics (e.g., smoking cessation rates or weight changes);

- Outcome analysis: Compare baseline and post-intervention results;

- Feedback loops: Incorporate participant and staff feedback to refine approaches.

Suggestions for how the smoking cessation intervention can be evaluated can be seen in Box 5.

Box 5: Evaluation for smoking cessation intervention in a community pharmacy

- Data collection:

- Description: Gather quantitative and qualitative data to assess the effectiveness of smoking cessation efforts;

- Examples:

- Conduct surveys to measure patient satisfaction and identify barriers to quitting;

- Record health metrics, such as CO levels, at baseline and during follow-up visits;

- Track the number of patients enrolled in the programme, the types of NRT prescribed and their quit rates.

- Outcome analysis:

- Description: Analyse collected data to determine the impact of the intervention;

- Examples:

- Compare the percentage of patients who successfully quit smoking within three and six months to baseline data;

- Analyse trends, such as whether specific interventions (e.g. one-on-one counselling versus workshops) yield higher quit rates;

- Assess the effectiveness of digital tools, such as smoking cessation apps, in improving patient engagement and outcomes.

- Feedback loops:

- Description: Use feedback from patients and staff to enhance the intervention’s design and delivery;

- Examples:

- Hold debrief sessions with pharmacy staff to discuss what worked well and identify areas for improvement;

- Incorporate patient feedback to refine communication strategies, such as simplifying messages or tailoring advice to individual needs;

- Update resources and methods based on recurring themes, such as offering more multilingual materials or increasing follow-up frequency.

Which intervention strategy is best suited for specific goals and target populations?

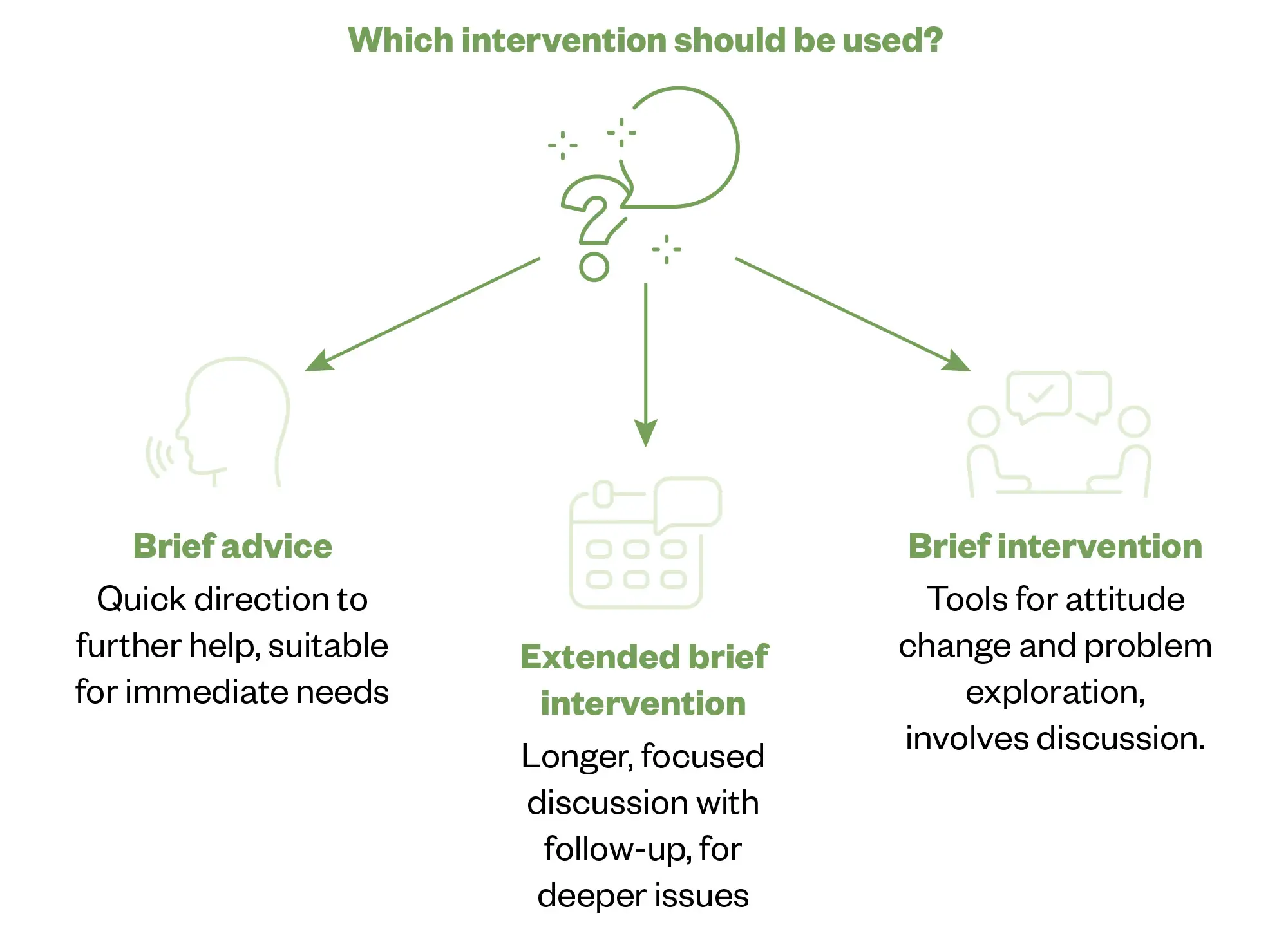

The choice of intervention strategy depends on the patient’s needs and the desired outcomes. For individuals who need minimal guidance or are not yet ready for behaviour change, MECC ‘Level 1: signposting (very brief intervention)’ is ideal, offering brief information and referrals to appropriate services. ‘Level 2: brief advice’ is effective for patients who need clear, concise recommendations and can take small actions, such as those seeking smoking cessation advice. ‘Level 3: behaviour change intervention’ works best for individuals motivated to make significant changes, offering structured support to help them adopt and sustain new behaviours (see Figure 3)10,11.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Sample scenarios aligning to the MECC Pyramid and mapping with NICE guidelines

The following scenarios highlight how different levels of interventions can be approached by considering the MECC pyramid and NICE guidelines.

Level 1: Signposting (very brief intervention)

Health topic: Seasonal flu vaccination22

Example of an intervention: A pharmacy team may identify a low uptake of flu vaccinations among working-age adults in their community. During routine dispensing interactions, staff can provide leaflets about the benefits of flu vaccination and offer information on booking an appointment.

Expected outcome: Leaflets may increase awareness and uptake of flu vaccinations, reducing community transmission rates.

Mapping with NICE guidelines: Signposting maps with NICE’s recommendation to raise awareness and encourage individuals to engage with health services11.

Level 2: Brief advice (brief intervention)

Health topic: Tobacco cessation23

Example of an intervention: During a medicines consultation, a pharmacist may identify a patient who uses smokeless tobacco and has mild hypertension. Applying the MECC approach, the pharmacist can spend two to three minutes providing brief advice on the health risks associated with tobacco use, the benefits of quitting and the availability of NRT. The patient can be referred to a local tobacco cessation support service.

Expected outcome: This advice may increase attempts to quit tobacco use and referrals to cessation programmes.

Mapping with NICE guidelines: Brief advice aligns with offering tailored support that motivates individuals to take the next step toward behaviour change11.

Level 3: Behaviour change intervention (extended brief intervention)

Health topic: Weight management24

Example of an intervention: A pharmacist can implement a structured weight management programme targeting patients with a BMI >30. The intervention may involve:

- Initial assessment: Setting personalised goals;

- Behavioural counselling: Weekly in-pharmacy sessions using motivational interviewing techniques;

- Digital support: Access to an app for tracking food intake and exercise.

Expected outcome: Participants may achieve significant reductions in BMI and improved metabolic markers.

Mapping with NICE guidelines: This maps with structured behaviour change interventions designed for individuals requiring more intensive support11.

Overcoming challenges in pharmacy health education

Pharmacy teams may face barriers to delivering health education. An example of a barrier is the time constraints that pharmacists may face. Strategies to address this include:

- Incorporating brief advice into routine interactions: Pharmacy teams can make use of the MECC framework, which encourages integrating brief health-promoting advice into everyday interactions with patients10. For example, while dispensing medicines or conducting a consultation, pharmacists can offer quick advice on smoking cessation, weight management or vaccination, ensuring that time spent with patients is optimised for both health education and service delivery.

Tip: Set a goal to incorporate at least one health-related message per patient interaction, focusing on the most relevant health issue based on their profile (e.g., age, current medicines or health status). - Use of technology for efficiency: Leveraging digital tools, such as apps or automated messaging systems, can streamline education. For instance, a pharmacy could send text message reminders about vaccination appointments, provide health tips via apps or even share educational videos on medicines management. Technology allows pharmacy teams to reach a larger number of patients with minimal additional time investment. More information about digital tools can be found in ‘Digital therapeutics: integration in practice’.

Tip: Implement a system for patients to receive educational materials post-consultation via email or text message to save time while reinforcing the advice. - Staff training for quick delivery: Train pharmacy staff to efficiently deliver vital health messages. Through role-playing scenarios and structured scripts, staff can deliver tailored advice within a short time window without sacrificing the quality of the interaction21.

Tip: Establish “key messages” that staff can quickly refer to during busy periods, ensuring that the most critical advice is always delivered, even under time pressures.

It may be difficult to engage patients with these interventions, some strategies to overcome this include:

- Ensure that health education materials are culturally sensitive and relevant to the patient population you serve. For example, provide information in multiple languages or use culturally appropriate images and examples in patient materials21.

Tip: Train pharmacy staff to be aware of cultural differences and to ask patients about their preferences and needs to tailor conversations effectively; - Involve patients in the decision-making process: Engage patients by involving them in setting their health goals and creating personalised action plans. For example, instead of simply telling a patient to stop smoking, ask them about their readiness to quit and discuss strategies that align with their preferences and lifestyle26.

Tip: Use motivational interviewing techniques, which focus on eliciting the patient’s own reasons for change and encouraging self-efficacy, thereby increasing engagement and commitment to health behaviour change; - Empathetic and active listening: Building rapport and trust is essential for effective patient engagement. Pharmacy teams should practice active listening, which means fully focusing on the patient, acknowledging their concerns and responding empathetically. This helps patients feel valued and heard, encouraging them to take action on health advice25.

Tip: Use open-ended questions, such as “How do you feel about managing your medication?” or “What concerns do you have about your health?”, to promote open dialogue; - Use of visual aids and interactive materials: Visual aids, such as charts, posters or apps, can help patients better understand their health conditions and the benefits of making lifestyle changes. Interactive tools, such as health trackers or medicines reminder apps, can keep patients engaged and motivated to follow through with health recommendations27.

Tip: Provide patients with a visual chart that tracks their progress, such as weight loss or smoking cessation, to give them a tangible sense of achievement as they make improvements.

Resource limitations may be a barrier to implementing health interventions. Examples to overcome resource limitations include:

- Collaborations with public health bodies and other agencies: Partnering with local health departments, public health organisations or non-profit organisations can help alleviate resource constraints. These bodies can provide funding, educational materials and support for health campaigns. For example, a pharmacy could collaborate with the local health authority to run flu vaccination campaigns, leveraging their resources to maximise reach.

Tip: Look for government or community grants dedicated to health promotion and reach out to local healthcare organisations for collaboration opportunities; - Utilising existing materials and resources: Many public health campaigns offer free or low-cost educational materials that pharmacies can distribute to patients. These can include brochures, posters or digital resources on topics like smoking cessation or healthy eating.

Tip: Utilise ready-made, evidence-based materials from reputable sources (e.g., NHS, WHO, or public health websites) to save on the cost and time of creating new content from scratch; - Community engagement for resource sharing: Partner with local schools, community centres or workplaces to create awareness about health education services offered by the pharmacy. In return, the pharmacy can offer to provide health education sessions or workshops, which can be a mutually beneficial exchange of resources.

Tip: Collaborate with local businesses to host health days or wellness events that provide the pharmacy with exposure and resources while benefiting the local community.

Conclusion

Designing and implementing effective health education interventions in primary care pharmacy settings is vital for improving public health outcomes. By understanding community health needs and leveraging frameworks, such as the MECC approach and NICE guidelines, pharmacies can address a wide range of health issues through tailored interventions. The MECC pyramid provides a structured approach for pharmacy teams to deliver impactful health education at varying levels of intensity based on patient needs.

The impact of health education interventions in pharmacy settings is significant. These interventions may contribute to improved health outcomes, such as reduced smoking rates, better chronic disease management and increased immunisation coverage. Interventions also may result in cost savings through the prevention of chronic conditions and the promotion of early intervention, which reduces long-term healthcare costs.

Furthermore, effective health education may foster stronger community trust, positioning pharmacies as integral parts of the local healthcare system and making them a vital resource for patients. With proper training, patient engagement and continuous evaluation, pharmacy teams can enhance their role as essential providers of accessible, evidence-based health education. By integrating these approaches, pharmacies will contribute to individual health improvements and support broader public health initiatives, creating healthier communities and a more sustainable healthcare system.

The RPS Foundation Pharmacist Framework

This article is aimed to support the development of knowledge and skills related to the following credentialing areas:

Domain 1.3: Has an awareness of the range of clinical, medicines-related and public health activities offered by a pharmacist across all sectors; seeks out opportunities to deliver different services in practice.

Domain 2.2: Works in partnership with individuals; viewing each individual receiving care as unique, seeking to understand the physical, psychological and social aspects for that person.

Domain 3.6: Demonstrates an understanding that data can support improving care; values the importance of the skills required for the interpretation, analysis and the effective use of data within clinical practice; considers how to use data to improve the outcomes for individuals.

Domain 4.3: Approaches the role with enthusiasm, seeks to demonstrate and promote the value of pharmacy across other healthcare professionals; educates the public about the role of the pharmacy team within individual healthcare management.

Domain 5.3: Recognises the value of members of the multidisciplinary team across the whole care pathway, drawing on those both present and virtually, to develop breadth of skills and support own practice.

Domain 8.1: Demonstrates a positive attitude to development within the role; has a desire and motivation to try new things.

- 1.Jaam M, Naseralallah LM, Hussain TA, Pawluk SA. Pharmacist-led educational interventions provided to healthcare providers to reduce medication errors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaismoradi M, ed. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0253588. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0253588

- 2.Rajiah K, Sivarasa S, Maharajan MK. Impact of Pharmacists’ Interventions and Patients’ Decision on Health Outcomes in Terms of Medication Adherence and Quality Use of Medicines among Patients Attending Community Pharmacies: A Systematic Review. IJERPH. 2021;18(9):4392. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094392

- 3.Gregory PAM, Austin Z. Understanding the psychology of trust between patients and their community pharmacists. Can Pharm J. 2021;154(2):120-128. doi:10.1177/1715163521989760

- 4.Steckler A, Allegrante JP, Altman D, et al. Health Education Intervention Strategies: Recommendations for Future Research. Health Education Quarterly. 1995;22(3):307-328. doi:10.1177/109019819402200305

- 5.Steed L, Sohanpal R, Todd A, et al. Community pharmacy interventions for health promotion: effects on professional practice and health outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online December 6, 2019. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011207.pub2

- 6.Zhang X, Tang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of primary healthcare practitioners regarding pharmacist clinics: a cross-sectional study in Shanghai. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1). doi:10.1186/s12913-024-11136-3

- 7.How pharmacy teams can provide health education. Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2023. doi:10.1211/pj.2023.1.195448

- 8.Thomson K, Hillier-Brown F, Walton N, Bilaj M, Bambra C, Todd A. The effects of community pharmacy-delivered public health interventions on population health and health inequalities: A review of reviews. Preventive Medicine. 2019;124:98-109. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.003

- 9.Turner R, Byrne-Davis L, Michael P, et al. Experiences of implementing the ‘Making Every Contact Count’ initiative into a UK integrated care system: an interview study. Journal of Public Health. 2023;45(4):894-903. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdad173

- 10.Making Every Contact Count (MECC): Consensus statement. Public Health England. March 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/making-every-contact-count.pdf

- 11.Behaviour change: individual approaches – public health guideline [PH49]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. January 2, 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph49

- 12.Statistics on Local Stop Smoking Services in England. NHS England. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-nhs-stop-smoking-services-in-england

- 13.Tackling high blood pressure through community pharmacy. Pharmacy Voice. 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5baa380bed915d2c266f7ee7/PV_Blood_Pressure_Report.pdf

- 14.Orabone AW, Do V, Cohen E. Pharmacist-Managed Diabetes Programs: Improving Treatment Adherence and Patient Outcomes. DMSO. 2022;Volume 15:1911-1923. doi:10.2147/dmso.s342936

- 15.Karlovitch S. Collaboration between pharmacists and general practitioners yields benefits. Pharmacy Times. June 30, 2020. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/collaboration-between-pharmacists-and-general-practitioners-yields-benefits

- 16.National breast and cervical cancer early detection program writing effective objectives. Centers for Disease Control’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/pdf/smartie-objectives-508.pdf

- 17.Setting SMART objectives. NHS Education for Scotland. 2017. https://learn.nes.nhs.scot/7204

- 18.World Health Organization. Target setting for low carbon sustainable health systems. 2024. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/377724/9789240094468-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 19.Johnson JL, Blefari C, Marotti S. Application of the COM-B model to explore barriers and facilitators to participation in research by hospital pharmacists and pharmacy technicians: A cross-sectional mixed-methods survey. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2024;20(1):43-53. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2023.10.002

- 20.Pharmacy: A Way Forward for Public Health – Opportunities for action through pharmacy for public health. Public Health England. 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a81c115ed915d74e33ffe09/Pharmacy_a_way_forward_for_public_health.pdf

- 21.About the Making Every Contact Count programme. NHS England. https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/making-every-contact-count/

- 22.Parracha ER, Rodrigues AT, Oliveira‐Martins S, et al. Pharmacist’s role in influenza immunisation: a scoping review. Pharmacy Practice and Res. 2024;54(4):273-286. doi:10.1002/jppr.1932

- 23.Brief interventions for tobacco cessation: A toolkit for pharmacists. The Hague: International Pharmaceutical Federation . 2024. https://www.fip.org/file/6106

- 24.Blebil AQ, Saw PS, Dujaili JA, et al. Using COM-B model in identifying facilitators, barriers and needs of community pharmacists in implementing weight management services in Malaysia: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1). doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08297-4

- 25.Consultation and communication skills for pharmacy OSCEs. Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2024. doi:10.1211/pj.2024.1.323096

- 26.Principles of person-centred practice for prescribing. Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2023. doi:10.1211/pj.2023.1.196714

- 27.Communicating risk: how pharmacists should use data in conversations with patients. Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2024. doi:10.1211/pj.2024.1.324651