Learning objectives

After reading the article, you should be able to:

- Define clinical reasoning;

- Describe why developing skills in clinical reasoning is important for pharmacists;

- Use the clinical reasoning cycle to support your decision making.

Pharmacists make clinical decisions daily that directly affect patient outcomes. The thought processes associated with clinical decisions are known as clinical reasoning — the ability to gather, analyse and use relevant information to benefit patients[1]. It is a cognitive process involved when choosing an appropriate management plan and includes shared decision-making[1]. Clinical reasoning is complex, requiring various mental processes to operate simultaneously during the clinical encounter, but it is an essential skill that pharmacists need to develop to expand their practice. Clinical reasoning is directly linked to patient safety and quality of care. The consequences of poor clinical reasoning can include diagnostic error, lack of evidence-based care, prescribing of unnecessary medication, inefficient management of medical conditions and the failure to implement relevant medical treatment[2].

Current pharmacy practice

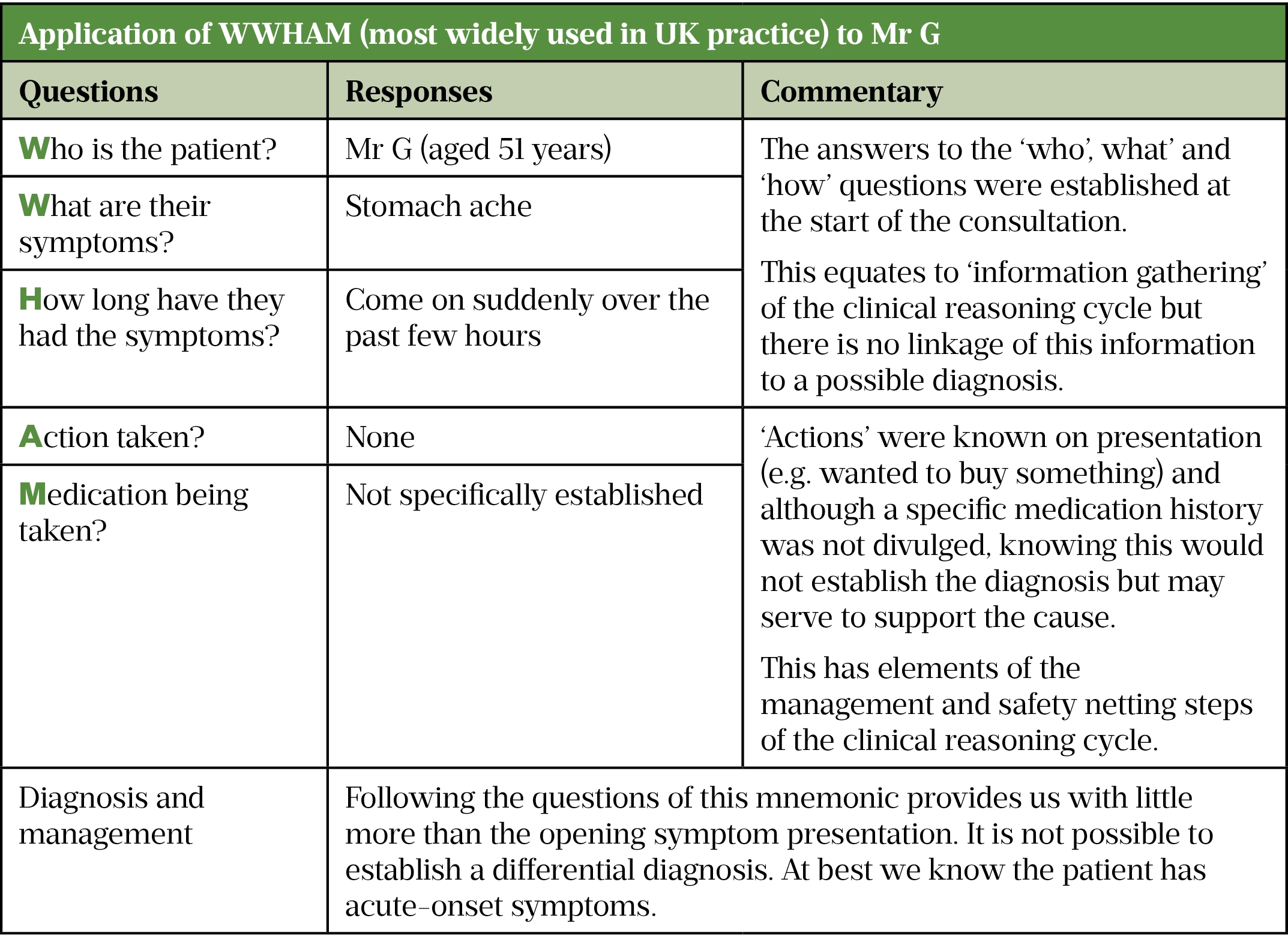

Pharmacists need to be able to competently manage patients to provide advice, treatment or onward signposting to others to ensure appropriate care. They also need to understand how a diagnosis has been reached. Studies have shown that clinical reasoning is a skill poorly performed and/or poorly articulated by pharmacists[3–6]. Mnemonics such as WWHAM (see Table 2) and ASMETHOD (see Table 3) have historically been widely advocated to guide information gathering during patient consultations[7]. However, their usefulness has been questioned and studies have shown that sole reliance on such methods leads to frequent incorrect diagnoses[8]. This is primarily owing to mnemonics being a generic ‘one size fits all’ approach that fails to consider the relevance of the information provided by the patient, which shapes subsequent information gathering. Additionally, asking set questions in a set order means that questions irrelevant to the examined condition might be asked, making the information acquired of little use[9].

Pharmacy educators are now starting to incorporate clinical reasoning in to undergraduate curricula as all newly qualified pharmacists from 2026 will have prescribing rights[10].

But just as importantly, the existing workforce requires upskilling, not only to take on new roles but also to supervise and train the next generation of pharmacists. However, and very importantly, the existing workforce requires upskilling, not only to take on new prescribing roles but also to supervise and train the next generation of pharmacists.

Clinical reasoning processes

To develop skills in clinical reasoning, it is important to understand the cognitive processes that underpin clinical reasoning.

There are several different types of reasoning used in clinical practice. Hypothetico-deductive reasoning is a common one, in which each competing diagnosis is considered and ruled out to leave one possible diagnosis. Abductive reasoning, often used in pharmacy, involves working backwards from a set of signs, symptoms and investigations to causes. The hypothesis that would best explain the available evidence is chosen but a limitation is that not all necessary information may be gathered to consider all possible diagnoses.

Dual process theory describes the two approaches to decision making[11]:

- Type 1 (intuitive) — this is a fast way of thinking that uses pattern recognition, illness scripts and heuristics;

- Type 2 (analytical) — this is a slow, controlled but high-effort way of thinking. It uses critical and logical thought and the generation and testing of hypotheses.

Heuristics are shortcuts that practitioners develop with experience to speed up their decision making. Illness scripts are a pharmacist’s own mental summary of a disease, which includes risk factors, pathophysiology and clinical characteristics[12]. They act as the mental ‘medical library’ that is perused to formulate a differential diagnosis. Experts tend to use ‘Type 1’ thinking much more than the novice but will switch into ‘Type 2’ thinking when faced with an unfamiliar case. Novices do not have the bank of illness scripts to use, or the experience to build pattern recognition, and their thinking tends to be more analytical and deliberate.

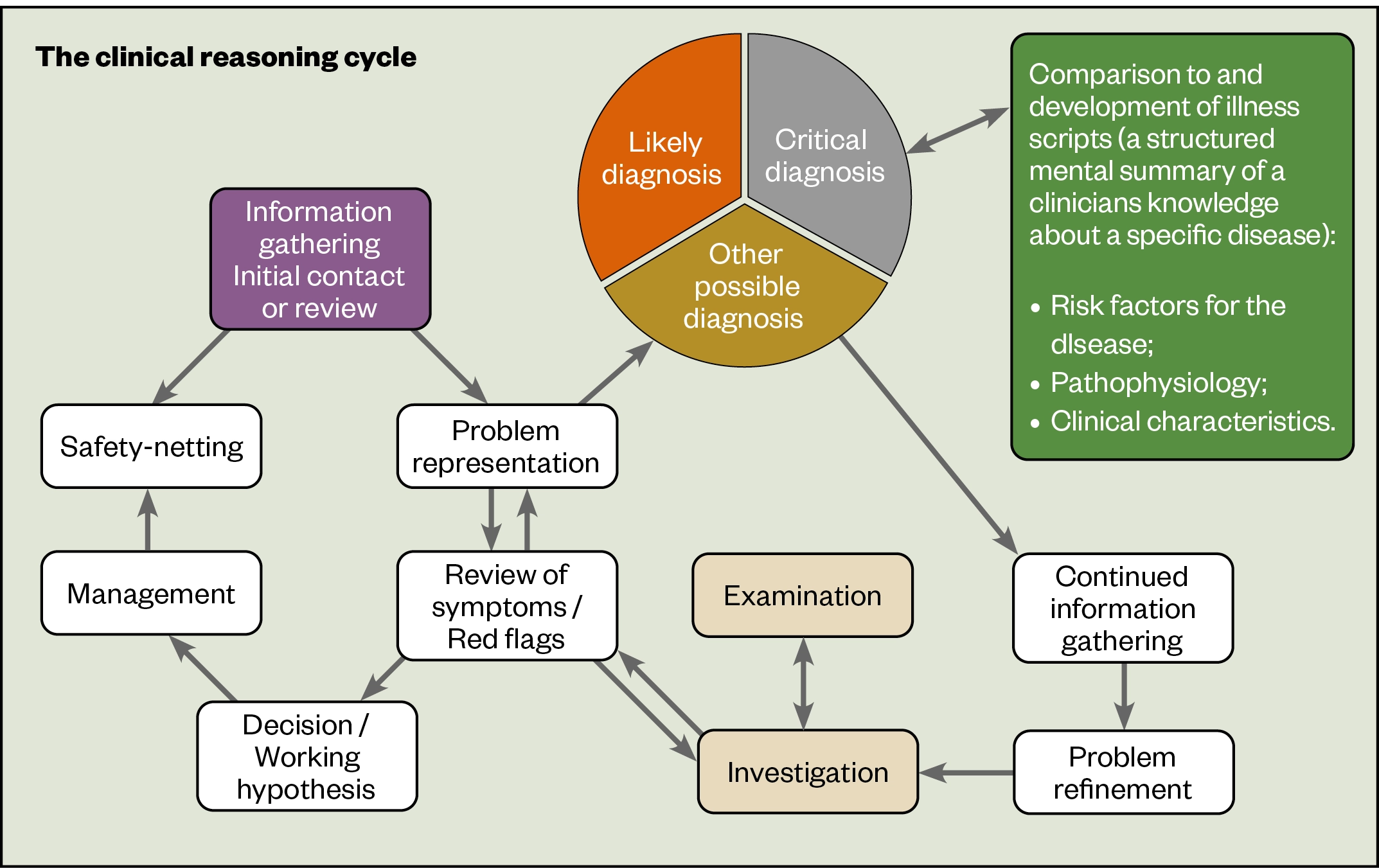

The clinical reasoning cycle

The clinical reasoning cycle sets out the cognitive processes that pharmacists may follow during a consultation (see Figure). It is not intended to be prescriptive or formulaic. For pharmacists who are less experienced at clinical reasoning, it is likely that they will work round the right-hand side of the clinical-reasoning cycle multiple times, testing each hypothesis in turn and often adopting deductive reasoning. With experience, reasoning will develop to become more intuitive and use decision-making shortcuts of pattern recognition and heuristics.

Gathering information

All patient consultations should start by gathering information from patient records, as well as non-verbal information through observation of the patient and verbal information offered by the patient themselves.

This will lead to problem representation: a succinct summary of the main clinical, social and psychosocial details gleaned from the initial patient encounter. This problem representation will be updated and refined as further information is revealed throughout the consultation.

Problem representation

The process of developing initial problem representation acts a ‘trigger’ for clinical reasoning. The pharmacist will consider likely causes of the patient’s symptoms and develop a differential diagnosis. This is where the pharmacist differentiates between two or more conditions that could be causing the symptoms. The pharmacist will refer to illness scripts to develop the differential diagnosis.

A useful way of organising the differential diagnosis is to consider the conditions in terms of likely diagnoses, other possible diagnoses (or unusual diagnoses) and critical diagnoses (i.e. conditions that could quickly deteriorate or become life-threatening). A likely diagnosis could also be a critical diagnosis.

Problem refinement

The next stage is problem refinement, which involves exploration of the clinical signs and symptoms, and understanding of disease prevalence, to explore the diagnoses and order them in terms of the likelihood of each being the cause of the presenting symptoms. A variety of approaches can help differentiate between the diagnoses.

- Semantic qualifiers — opposing statements relating to symptoms presentation (e.g. ‘Do you have a dry cough or a productive cough?’);

- Red flags — troublesome or worrying symptoms that are suggestive of a higher acuity patient (who may be more acutely ill or who has more immediate and complex health needs);

- Systems review — this assesses the overall health of a body system[13]. In a systems review of the gastrointestinal system, questions may be asked about difficulties with swallowing, stomach pain and bowel movements. By exploring system health, groups of diagnoses that fall within a system can be considered.

Through in-depth gathering of information and the use of clinical reasoning to structure a consultation around exploration of a differential diagnosis, a high diagnostic probability can be achieved. Examinations and tests are normally reserved until a well-formed hypothesis has been derived and are often used to confirm or differentiate between similar conditions.

Working hypothesis and management plan

Eventually, the pharmacist will develop a working hypothesis, or reach a probable diagnosis. This will be based on probability and not certainty and is the most likely cause of the presenting symptoms.

A management plan should then be developed and this itself will test the hypothesis — if the management plan results in symptom abatement, the diagnosis is likely to be correct.

Safety netting

Pharmacists must be mindful that the diagnosis may be incorrect, or that more serious symptoms may develop. It is important to ‘safety net’ the patient, considering[14]:

- If I am right, what do I expect to happen?;

- How will I know if I am wrong?;

- What would I do then?

The patient must be given clear, precise and tailored guidance on:

- How quickly the management plan should start to work;

- What symptoms to look out for that would indicate that the management plan is not working;

- Specific symptoms to look out for that may indicate that the diagnosis is incorrect;

- What to do if alarming symptoms arise.

Pharmacists working under an existing diagnosis (e.g. running a disease-review clinic) are more likely to limit their reasoning to the left-hand side of the cycle. However, red flags must still be explored and systems-review questions asked. If the patient reports apparent disease progression, reduced disease control, or new symptoms, including possible adverse drug reactions, then a differential diagnosis should be considered.

Clinical reasoning in practice: a case of upper abdominal pain

Presentation

Mr G (aged 51 years) presents to the pharmacy at lunchtime, complaining of stomach ache. He has popped out of the office to buy some antacid tablets. He said the pain came on after breakfast and he expected the pain to go away on its own, but it has been bothering him all morning.

Problem representation

Acute onset abdominal pain in a middle-aged adult male.

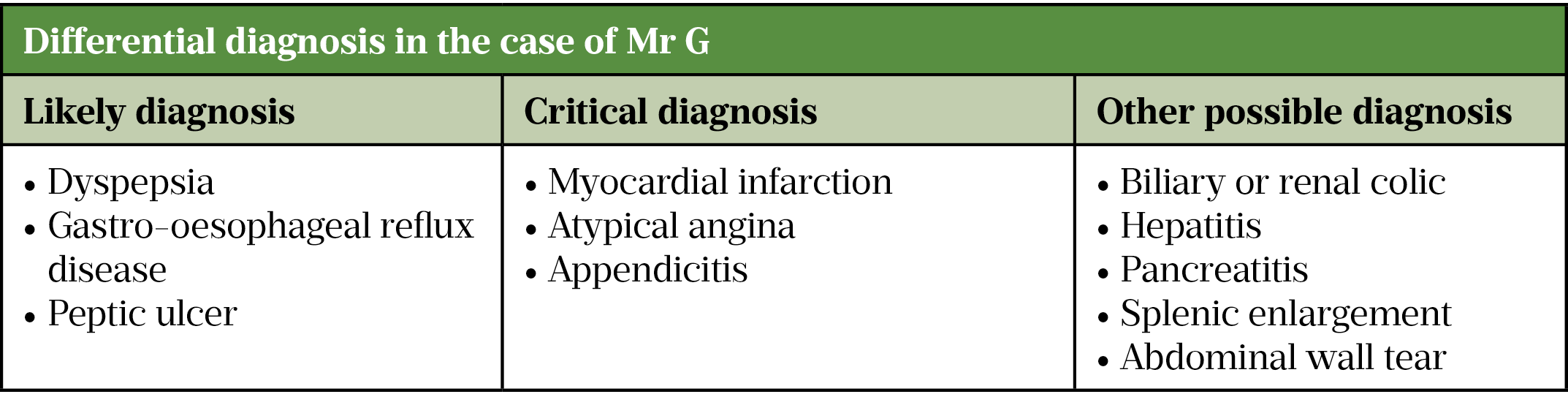

Hypothesis generation (likely, critical and other possible diagnosis)

Considering Mr G’s age and presenting symptoms, there are many possibilities to consider. Abdominal pain is associated with the gastrointestinal tract, but it can also be cardiovascular or musculoskeletal in origin. It is important to establish the exact location of his pain, as gastrointestinal pain is often associated with a particular structure/organ.

The use of a pain-specific mnemonic, such as SOCRATES (site, onset, character, radiation, associated symptoms, time, exacerbating or relieving factors, severity), could assist with this. The patient indicated that the site of the pain was in the upper abdomen, so a differential diagnosis will focus on conditions that affect that area and exclude those that typically affect the lower abdomen (see Table 1).

Information gathering

Three conditions have been identified as likely diagnoses, so the pharmacist should ask questions about other signs and symptoms. Ask review-of-systems and red-flag questions to consider the likelihood of the pain being cardiovascular in origin. There is no set question order, but the responses given by Mr G will influence subsequent questions. Table 2 and Table 3 show how limited the usefulness of a mnemonic approach would be.

Problem refinement

Further questioning reveals that Mr G is in some discomfort, but does not have nausea or vomiting. He describes the pain as constant, but limited to the upper abdominal region and not radiating anywhere (e.g. down his left arm). Mr G cannot recall any particular trigger of his symptoms and it was not made worse by walking to the pharmacy. The next step is to deduce if any of the three likely diagnoses are the cause of his symptoms and consider the likelihood of any of the critical diagnoses.

Updated problem representation

A 51-year-old male with post-prandial acute onset of constant upper abdominal pain, with no other significant associated symptoms.

The location of the pain is not very helpful, as all three likely diagnoses present with mid-upper-abdominal symptoms. The fact he has not described heartburn symptoms is useful — heartburn is a strong predictor of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). Given that Mr G’s predominant symptom is constant pain that came on after eating, a differential diagnosis of peptic ulcer becomes likely, further supported by his age.

GORD classically exhibits as burning, dyspepsia is usually described as discomfort, but ulcers are more painful, described as a gnawing or sharp and stabbing pain. Questions about the pain sensation, whether anything aggravates or relieves the pain, and previous history of the presenting complaint should be asked. Mr G describes the pain as sharp and stabbing, and reports having had this type of pain a few months ago. However, he cannot recall if it was better or worse after eating food.

Updated problem representation

A 51-year-old male with a second occurrence of acute, post-prandial onset of a sharp, stabbing pain in the upper abdominal area, with no significant associated symptoms, with no reported triggers or exacerbating or relieving factors.

The diagnosis is more likely to be an ulcer than GORD or dyspepsia. Seek a medication history, because non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, bisphosphonates, corticosteroids and selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors are known risk factors for developing ulcers. A family history of peptic ulcer disease is also a risk factor. A full social history should be taken as smoking, alcohol consumption, dietary choices and stress are all risk factors.

Understanding the broader patient context assists with the reasoning process, adds weight to the diagnostic decision, and assists with patient management, including lifestyle advice.

Management and safety netting

Given the uncertainty with the diagnosis, it is important before formulating a treatment plan that red flags or ‘ALARM’ symptoms (anaemia, loss of weight, anorexia, recent onset of progressive symptoms, melaena/black stools) are explicitly asked about, even if the patient has stated they had no other symptoms. If any of these are present, the patient should be referred to a GP.

Although it is unlikely, given Mr G’s predominant symptom of constant pain, a critical diagnosis of appendicitis must still be considered, as early presentations of appendicitis can start with centralised pain before moving to the right lower quadrant.

It would seem prudent to recommend Mr G see a medical practitioner for a second opinion.

Techniques to improve performance

- Reflection

- Thinking about what occurs before, during and after situations with the purpose of developing a greater understanding of both the self and the situation, so that future encounters with the situation are informed by previous encounters.

- Metacognition

- Described as ‘thinking about thinking’ and refers to the ability to monitor one’s own cognitive processes;

- Using the ‘think aloud technique’ to verbalise your thoughts.

Useful resources to aid clinical reasoning

Weiss MC. Diagnostic decision making: The last refuge for general practitioners? Social Science & Medicine 2011;73:(3)375–382.

Cooper N, Frain J. ABC of Clinical Reasoning 2nd edition. (ABC series), 2022. BMJ Publishing. ISBN 1119871514.

Rutter P. Differential diagnosis for non-medical prescribers: A case based approach, 2024. Elsevier. ISBN 0443116040.

This article has been reviewed and updated by co-author Paul Rutter to ensure it remains relevant, following its original publication in February 2022.

- 1Frain J. Clinical reasoning: an overview, p1. In: ABC of Clinical Reasoning. John Wiley and Sons 2017. 64.

- 2Scott IA. Errors in clinical reasoning: causes and remedial strategies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1860–b1860. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1860

- 3Anakin MG, Duffull SB, Wright DFB. Therapeutic decision-making in primary care pharmacy practice. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2021;17:326–31. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.005

- 4Gregory PAM, Whyte B, Austin Z. How do community pharmacists make decisions? Results of an exploratory qualitative study in Ontario. Can Pharm J. 2016;149:90–8. doi:10.1177/1715163515625656

- 5Chernushkin K, Loewen P, De Lemos J, et al. Diagnostic Reasoning by Hospital Pharmacists: Assessment of Attitudes, Knowledge, and Skills. CJHP. 2012;65. doi:10.4212/cjhp.v65i4.1155

- 6Haider I, Luetsch K. Pharmacists’ advice and clinical reasoning in relation to cardiovascular disease risk factors – A vignette case study. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2020;16:568–73. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.08.006

- 7Sinopoulou V, Rutter P. Approaches to teaching diagnostic skills to pharmacy students: a global perspective. Pharm Ed 2019;19:34–39.https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/en/publications/approaches-to-over-the-counter-medications-teaching-in-pharmacy-e

- 8Sinopoulou V, Gordon M, Rutter P. A systematic review of community pharmacies’ staff diagnostic assessment and performance in patient consultations. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2019;15:1068–79. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.10.003

- 9Rutter PM, Harrison T. Differential diagnosis in pharmacy practice: Time to adopt clinical reasoning and decision making. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2020;16:1483–6. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.020

- 10New Standards for Initial Pharmacy Education and Training Approved. General Pharmaceutical Council . 2020.https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/news/new-standards-initial-education-and-training-pharmacists-approved (accessed Feb 2022).

- 11Croskerry P. Clinical cognition and diagnostic error: applications of a dual process model of reasoning. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2009;14:27–35. doi:10.1007/s10459-009-9182-2

- 12Schmidt HG, Rikers RMJP. How expertise develops in medicine: knowledge encapsulation and illness script formation. Med Educ. 2007;0:071116225013002-??? doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02915.x

- 13Innes J, Dover A, Fairhurst K. Macleod’s Clinical Examination . 14th ed. London: : Elsevier Health Sciences 2018. https://www.elsevier.com/books/macleods-clinical-examination/innes/978-0-7020-6993-2 (accessed Feb 2022).

- 14Neighbour R. The Inner Consultation. London: : Radcliffe Publishing 1991.