Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the principles for management of rheumatoid arthritis;

- Understand how pharmacists in different sectors can support patients living with rheumatoid arthritis;

- Distinguish between the different disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and their monitoring requirements;

- Consider the non-pharmacological management options for rheumatoid arthritis.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune condition, characterised by inflammation of the joint synovium. It affects around 1% of the UK population, with a female:male ratio of 2–4:1 and peak age of onset at between 40 years and 70 years[1–3]. It is a symmetrical polyarthritis, typically affecting the small joints of the hands, wrists, knees, ankles and feet in a relapsing-remitting course, where disease flares can be sudden and unpredictable. Extra-articular manifestations may affect the lungs, skin, blood, eyes and other organs.

The cause of RA remains unclear, however it is likely a mix of genetic, environmental and other factors, which interact and trigger autoimmunity, occurring years before clinical symptoms are present. Smoking is the most important environmental trigger, increasing disease susceptibility by 20- to 40-fold when associated with genetic factors[4].

There is no cure for RA. In early disease, management aims to suppress disease activity, induce remission, prevent loss of function, minimise joint damage, control pain and enhance self-management of flares. Early treatment is associated with better disease control and improved long-term outcomes[5].

Pharmacists across all sectors can support the timely and effective management of patients with RA to improve outcomes (see Figure 1 for examples).

Assessing disease activity

An individual’s level of disease activity can be assessed quantitatively with the 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28), a composite score calculated from the number of tender and swollen joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (an inflammation marker) or C-reactive protein levels, and a self-reported patient assessment of general health status according to a 100mm visual analogue scale[6–8].

Management

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) should be started as soon as possible following diagnosis, ideally within the ‘window of opportunity’, considered as 12 weeks from symptom onset[5]. DMARDs are medicines used in the management of RA that demonstrate the capacity to inhibit structural damage to cartilage and bone. Uncontrolled systemic inflammation is associated with higher rates of infections, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, malignancies, significant morbidity and early mortality. ‘Treat to target’ is a core principle for management, proven to result in improved functional and radiographic outcomes[9]. This means the clinician and patient agree on a treatment goal, and the patient is monitored monthly, with timely treatment escalation, until the treatment target is achieved[10].

Symptom control

Glucocorticoids act by inhibiting cytokine release and are effective at reducing inflammation and suppressing the immune system to give rapid relief of symptoms, but long-term use is restricted owing to their unfavourable adverse effect profile. Short-term use can be considered to help control disease activity in newly diagnosed patients, during flare ups or while awaiting the therapeutic onset of new or recently changed DMARDs. Glucocorticoids should be tapered as rapidly as is clinically feasible. Depending on the number of affected joints, they may be administered as an intra-articular injection for local action or as an intramuscular depot injection, intravenous infusion or short-term oral therapy for systemic effects. Bone protective therapy and gastro protection are indicated as co-therapy in certain patient cohorts. In 2020, NHS Improvement released a Steroid Emergency Card to be issued to patients receiving steroids, in accordance with a National Patient Safety Agency alert, to support early recognition and treatment of adrenal crisis in adults[11,12].

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective in reducing pain, swelling and stiffness associated with RA, but have no effect on long-term disease control or radiographic outcome so are typically reserved for symptom control during periods of flares or while awaiting the onset of DMARDs. It is important that their use does not mask the need for optimisation of DMARD therapy. Both non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors should be prescribed at their lowest effective dose, for the shortest period, with a gastro-protective proton pump inhibitor[10].

Disease modification

There are three categories of DMARDs:

- Conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs);

- Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs);

- Targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs).

For full prescribing guidance, including cautions and contraindications, see summaries of product characteristics. For guidance on use in pregnancy, see the latest British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) guidelines[13].

Conventional synthetic DMARDs

In England, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends initiating csDMARD monotherapy as first-line treatment, using oral methotrexate, leflunomide or sulfasalazine[10]. Hydroxychloroquine can be used as an alternative for patients with mild or palindromic disease. The csDMARD dose should be escalated, as tolerated, to achieve a treatment target of remission or low disease activity. An additional csDMARD (oral methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine or hydroxychloroquine) can be added in a step-up strategy when the treatment target has not been achieved, despite dose escalation of the first csDMARD. If a csDMARD is not tolerated, the patient can be switched to another[10]. Each csDMARD has a unique mechanism of action within the inflammatory cascade.

Oral methotrexate is generally used as a first-line csDMARD in RA unless the patient has a comorbidity (e.g. significantly impaired hepatic function, alcoholism, pregnancy, known active peptic ulceration, immunodeficiency, estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <10 mL/min) which precludes its use[14]. It has an onset of action of around 4–12 weeks. Common starting doses are 10–15mg/week, titrated up to 15–25mg/week. Lower doses and slower titration are recommended in patients with renal impairment[15]. Methotrexate can be given by subcutaneous injection when patients are unable to tolerate oral doses because of gastric side effects, or to increase bioavailability and efficacy[16]. BSR guidelines recommend patients taking methotrexate are co-prescribed a minimum dose of 5mg folic acid once weekly to help reduce the risk of side effects and improve tolerability (administration should be avoided on the day methotrexate is administered)[17]. Methotrexate has been the subject of national drug safety alerts in England and measures are in place to reduce the risk of fatal overdose owing to inadvertent daily dosing instead of weekly dosing[18,19].

Leflunomide may be considered as an alternative to methotrexate as part of the initial treatment strategy in patients where methotrexate is contraindicated or there is early intolerance. Leflunomide has both immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive characteristics[20]. When given as an oral tablet, with a loading dose of 100mg daily for three days followed by a maintenance dosage of 10–20mg daily, its therapeutic effect starts after 4–6 weeks, and further improvement may be seen for up to 4–6 months. However, many clinicians do not use this loading dose regimen because patients are unable to tolerate the associated gastrointestinal side effects. The use of leflunomide has been associated with both haematological and hepatotoxic side effects[21]. Leflunomide can also cause hypertension; a patient’s blood pressure should be checked before commencing treatment and periodically thereafter.

Sulfasalazine can be used as an alternative to methotrexate. A five-year follow-up study showed equivalent disease activity outcome in those treated with sulfasalazine and methotrexate as the first csDMARD, but those treated with methotrexate had lower rates of erosions and higher levels of drug persistence over time[22]. Sulfasalazine is usually administered by oral tablet (plain or enteric coated) and has an onset of action of 6–12 weeks[23]. To reduce the side effect of nausea, the dose is usually titrated upwards from 500mg daily, increasing by 500mg each week to a maintenance dose of 2–3g daily, usually taken in two divided doses. If a patient struggles with tolerance, a more gradual dose titration can be used. Haematological abnormalities have occurred rarely with the use of sulfasalazine, and patients should be counselled to report unexplained bleeding, bruising, purpura, sore throat, fever or malaise. Patients should also be warned that sulfasalazine can colour urine, tears and stain contact lenses yellow-orange[24].

Hydroxychloroquine may be used in milder disease, disease with palindromic onset or as an additive therapy to other csDMARDs, although its efficacy as a DMARD or additional benefit in triple therapy regimes has been questioned in some systematic reviews[14].

Hydroxychloroquine is usually given as an oral tablet, typically in one to two divided doses per day. Product literature recommends a maximum dose of 6.5mg/kg/day based on ideal body weight, but the Royal College of Ophthalmologists recommends keeping the dose <5mg/kg/day based on actual body weight. Patients should be referred to a secondary care ophthalmologist after five years of treatment for ongoing annual retinopathy screening, or after a year if risk factors for retinopathy are present[25]. Risk factors include:

- Concomitant tamoxifen use;

- Impaired renal function (eGFR <60mL/min/1.73m2)

- Hydroxychloroquine dose (>5mg/kg/day)

In the UK, BSR has standardised recommendations for monitoring of csDMARDs (see Table 1)[17].

Standard laboratory monitoring for csDMARDs is: full blood count (FBC), creatinine/calculated GFR, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and/or aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and albumin blood tests.

Tests are completed at initiation, then every 2 weeks for 6 weeks. Once the patient is stable on a prescribed dose, test are completed monthly for 3 months, then at least every 12 weeks thereafter (more frequent monitoring is appropriate in patients at higher risk of toxicity). Following a dose increase, monitoring is required every 2 weeks for 6 weeks, and then reverts to the previous schedule. C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is also typically monitored for DAS-28 calculation to assess efficacy.

Biologic and targeted synthetic DMARDs

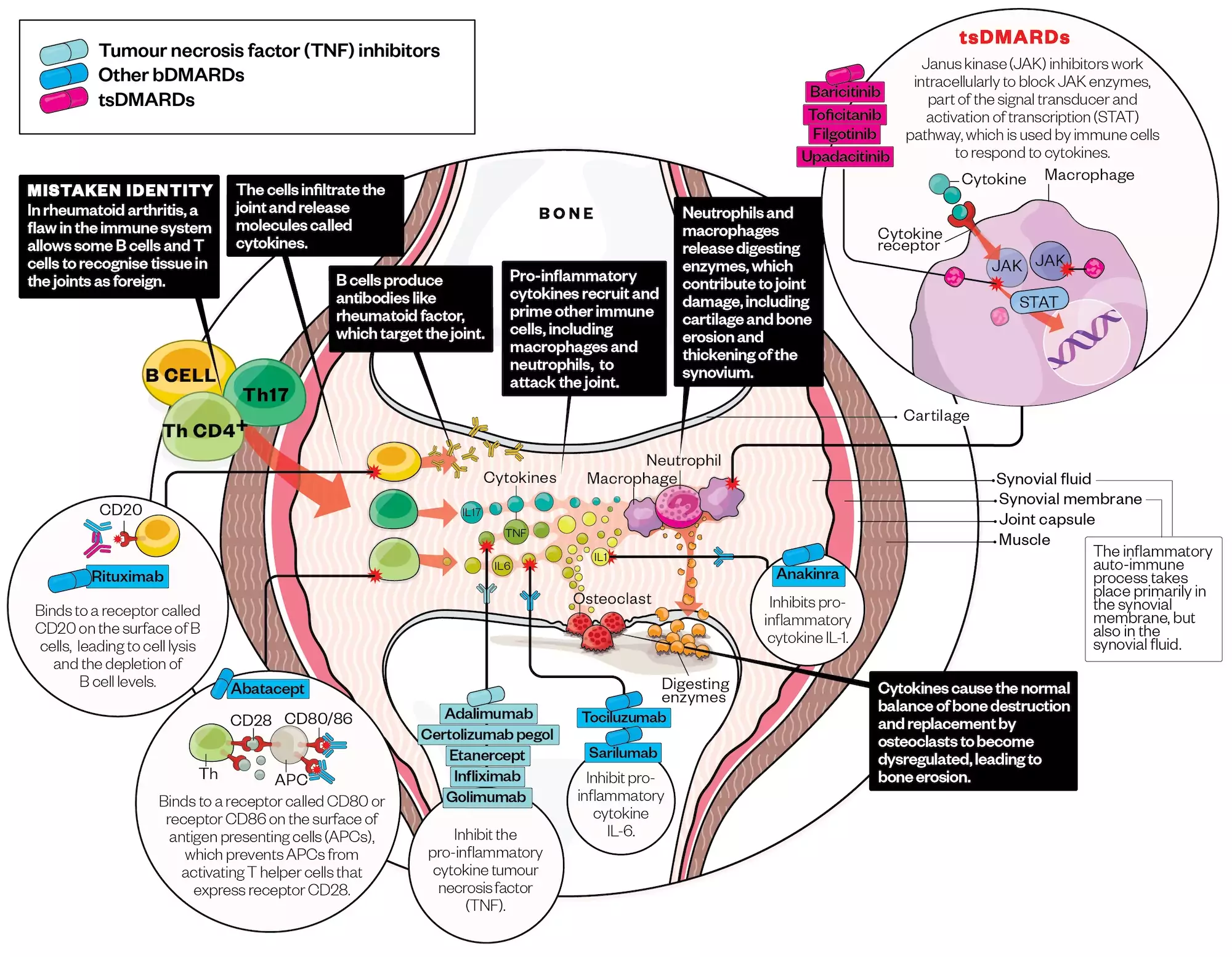

bDMARDs used in RA target specific immune-mediated pathways involved in the pathophysiology of the condition and have markedly changed the management and outcome of RA (see Figure 2). They are derived from living cells through highly complex manufacturing processes.

Alisdair Macdonald (alisdairmacdonald.co.uk)

Current bDMARDs available for the management of RA include:

- Adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab and infliximab — originator tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) which exert their effects by blocking TNF-α, resulting in dampening of the inflammatory cascade and blocking IL-1 activity. TNFi therapy has been shown to reduce the signs and symptoms of RA, improve physical function and slow the progression of joint damage;

- Rituximab — a monoclonal antibody that binds specifically to the transmembrane antigen CD20, depleting B-cells, affecting B- and T-cell interaction, antigen presentation and cytokine production;

- Abatacept — a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen-4 inhibitor. It causes attenuation of T-cell activity by blocking a co-stimulatory signal, thereby reducing expression of activation markers, secretion of cytokines and stimulation of macrophages to reduce inflammation;

- Tocilizumab and sarilumab — monoclonal antibodies that block the actions of interleukin-6 (IL-6), a multifunction cytokine which regulates immune responses, acute-phase reactions, haematopoiesis and bone metabolism. IL-6 blockade is associated with reduced production of acute-phase proteins and auto-immune antibodies[26–28].

Biosimilar products available for the management of RA include adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab and rituximab, with others in the pipeline.

In 2017, janus kinase inhibitors (JAKis) became the first available therapies in a new class of treatment, known as tsDMARDs.

JAKis inhibit the activity of one or more of the janus kinase family of enzymes. There are currently four JAKi approved for the management of RA:

- Tofacitinib and baricitinib — active on the majority of the four JAK family members (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 and TYK2) with some selectivity towards JAK1 and JAK3 (tofacitinib) and JAK1 and JAK2 (baricitinib);

- Filgotinib and upadacitinib — developed with JAK-1 selectivity in an attempt to improve the safety profile by minimising the effects on JAK3 and, especially, JAK2.

JAKis have recently been the subject of a Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) investigation owing to safety concerns, resulting in the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency recommending to reduce risks of major cardiovascular events, malignancy, venous thromboembolism, serious infections and increased mortality, including important restrictions on prescribing[29].

Escalation to either a bDMARD or a tsDMARD is undertaken when there is inadequate response or intolerance to csDMARDs. Eligibility in England requires a patient to have severe or moderate disease activity (measured by DAS28) despite having tried at least two csDMARDs, including methotrexate. NICE stipulates which b/tsDMARD therapies can be considered for first-line use or after previous b/tsDMARD failure in severe RA, as well as treatments recently approved for use in moderate RA[3,30–36].

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses comparing use of biologics in RA have shown differing efficacy outcomes, with some suggesting comparable efficacy and safety between the different b/tsDMARDs, whereas others demonstrated favourable outcomes with non-TNFi therapies compared to TNFis[37–39].

NICE stipulates that rituximab, golimumab, infliximab and abatacept must be used in combination with methotrexate, but local agreements may vary. Combination therapy using a b/tsDMARD and methotrexate (termed a csDMARD ‘anchor therapy’) is advocated because of superior efficacy and reduced risk of b/tsDMARD immunogenicity (resulting in secondary treatment failure) when combination therapy is used, compared with b/tsDMARD monotherapy[40].

In England, NICE recommends continuing treatment with a b/tsDMARD therapy only if there is a moderate response measured using EULAR criteria at six months after starting therapy[10].

In patients who have achieved sustained remission or low disease activity in the absence of long-term glucocorticoids, b/tsDMARD or csDMARD dose reduction may be possible[41,42].

The BSR recommendations describe standardised pre-treatment investigations and screening tests to assess for comorbidity, as well as standardised monitoring of bDMARD therapies and management of comorbidity (see Table 2)[43].

Standard pre-treatment investigations for b/tsDMARDs include:

- FBC, creatinine/calculated GFR, ALT and/or AST, albumin blood tests;

- Chest radiograph;

- Tuberculin skin test (TST) or IFN-γ release assay (IGRA) or both as appropriate (e.g. QuantiFERON) — N.B. immunosuppression may hinder TST interpretation);

- Serology for hepatitis B (HBsAg, HBsAb, HBcAb) and hepatitis C (anti-HCV);

- HIV serology if risk factors for HIV infection;

- Consider varicella zoster virus antibody test if no positive history of previous varicella infection and, if negative, consider varicella zoster vaccination if no contraindications;

- Consider herpes zoster (Shingles) vaccination if patient >50 years and no contraindications;

- Consider hepatitis B vaccination for at-risk patients.

Standard monitoring for b/tsDMARDs includes FBC, creatinine/calculated GFR, ALT and/or AST, albumin blood tests every 3–6 months (in practice this could be 3-monthly for the first 12 months and then 6-monthly), unless the patient is already having more frequent monitoring for concomitant csDMARD. CRP or ESR are also typically monitored for DAS-28 calculation to assess efficacy.

When making a decision about choice of bDMARD or tsDMARD therapy, the clinician and patient should consider the individual patient’s preferences, clinical parameters and cost effectiveness in a shared decision making process (see Table 3).

Non-pharmacological management

Patients should have access to a multidisciplinary team (MDT) to address both the pharmacological and non-pharmacological aspects of disease management[10].

Patients with RA require access to specialist physiotherapy, with regular, periodic review to assess function and design a programme to aid pain relief and rehabilitation. The programme should aim to improve general fitness, enhance joint flexibility and muscle strength, and overcome other functional impairments through regular and individually tailored exercises. Physiotherapists may also provide education about use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulators and wax baths to provide short-term symptom relief.

Occupational therapy aims to provide support and aid patients in improving function, and limit disability in their activities of daily living (e.g. using devices to alleviate tasks that are difficult for those with restricted manual dexterity, such as twisting lids to open bottles). Some patients may benefit from a tailored strengthening and stretching hand exercise program to reduce pain and dysfunction of the hands or wrists if they have been on a stable drug regimen for RA for at least three months (or if they are not on drug treatment).

Patients with foot problems associated with their RA should have access to a podiatrist for assessment of their foot health needs. Functional insoles and therapeutic footwear (orthotics) should be available, if indicated.

Patients with RA may need psychological support and counselling to help them adjust to living with their condition. They may benefit from sessions with a clinical psychologist, ideally one specialising in rheumatology or the management of chronic conditions. Other psychological interventions include relaxation, stress management and cognitive coping skills.

There is no strong evidence that diet modification and complementary therapies benefit management of RA. However, patients could be encouraged to follow the principles of a Mediterranean diet owing to its focus on anti-inflammatory foods. If patients are keen to try a complementary therapy, they should be advised that although some may provide short-term symptomatic benefit, there is little or no evidence for disease-modifying effects or long-term efficacy. If they pursue complementary therapies, their choice should not prejudice the MDT or affect the care offered, nor should it replace conventional treatment.

As with any other chronic condition, it is important to support a patient to self-manage their condition and regain control when experiencing a flare-up. Advice on how patients can self-care during a flare-up is provided below:

- Increasing or starting “when required” analgesics within safe, appropriate doses;

- Using cold therapy (ice packs wrapped up or cold water) to soothe hot, red, swollen joints, or using warm therapy (warm water, warm bath, heat pads, hot water bottle or heat bags) to relieve stiff joints. Alternating between hot and cold therapy can be useful;

- Using gentle stretching and a range of motion exercises to help improve joint function. Movement can help keep joints flexible, reduce pain, and improve balance and strength;

- Balancing activities with plenty of rest during a flare-up (pacing);

- Using temporary aids — for example a walking stick if suffering with a flare in the knee;

- Considering stress-relieving activities (e.g. yoga, deep breathing, meditation);

- Letting friends, family and colleagues know, so they are aware and can help if needed;

- Speaking to their GP or specialist rheumatology team if the flare-up is severe or does not resolve in case they need a prescription for corticosteroids to help manage the acute problem;

- Identifying and avoiding potential triggers for a flare-up;

- Assessing the frequency and severity of flare-ups and, if happening regularly, speaking to their GP or specialist rheumatology team in case a review of DMARD(s) is needed;

- Establishing how the flare-up is impacting their daily life and activities, and seeking help from a support network;

- Accessing supportive websites from the secondary care provider or patient charities.

Further resources

Diagnosis

- BMJ Best Practice: Rheumatoid arthritis — Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment

- American Family Physician: Rheumatoid arthritis: common questions about diagnosis and management

Monitoring

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Rheumatoid arthritis — management and monitoring algorithm

Non-pharmacological management

Arthritis Research UK: Self-help and daily living — Keep moving

This article has been reviewed by the expert authors to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in The Pharmaceutical Journal in November 2023.

- 1Scott IC, Whittle R, Bailey J, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthritis epidemiology in England from 2004 to 2020: An observational study using primary care electronic health record data. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe. 2022;23:100519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100519

- 2Symmons D. The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United Kingdom: new estimates for a new century. Rheumatology. 2002;41:793–800. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/41.7.793

- 3Rheumatoid arthritis in over 16s. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs33 (accessed November 2023)

- 4Lundström E, Källberg H, Alfredsson L, et al. Gene–environment interaction between the DRB1 shared epitope and smoking in the risk of anti–citrullinated protein antibody–positive rheumatoid arthritis: All alleles are important. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2009;60:1597–603. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24572

- 5Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis not previously treated with DMARDs or after conventional DMARDs only have failed. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta375 (accessed November 2023)

- 6Rheumatoid arthritis — Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. BMJ Best Practice. 2023. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/105 (accessed November 2023)

- 7Wasserman A. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Common Questions About Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:455–62.

- 8Wells G, Becker J-C, Teng J, et al. Validation of the 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) and European League Against Rheumatism response criteria based on C-reactive protein against disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and comparison with the DAS28 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2008;68:954–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2007.084459

- 9Mian A, Ibrahim F, Scott DL. A systematic review of guidelines for managing rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2019;3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-019-0090-7

- 10Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng100 (accessed November 2023)

- 11National Patient Safety Alert – Steroid Emergency Card to support early recognition and treatment of adrenal crisis in adults. NHS England. 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/national-patient-safety-alert-steroid-emergency-card-to-support-early-recognition-and-treatment-of-adrenal-crisis-in-adults/ (accessed November 2023)

- 12Adrenal Crisis Information. Society for Endocrinology UK. 2023. https://www.endocrinology.org/adrenal-crisis (accessed November 2023)

- 13Russell MD, Dey M, Flint J, et al. Executive Summary: British Society for Rheumatology guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding: immunomodulatory anti-rheumatic drugs and corticosteroids. Rheumatology. 2022;62:1370–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keac558

- 14Haegens LL, Huiskes VJB, van der Ven J, et al. Factors Influencing Preferences of Patients With Rheumatic Diseases Regarding Telehealth Channels for Support With Medication Use: Qualitative Study. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7:e45086. https://doi.org/10.2196/45086

- 15Methotrexate. The Renal Drug Database. 2023. https://renaldrugdatabase.com/monographs/methotrexate (accessed November 2023)

- 16Schiff MH, Jaffe JS, Freundlich B. Head-to-head, randomised, crossover study of oral versus subcutaneous methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: drug-exposure limitations of oral methotrexate at doses ≥15 mg may be overcome with subcutaneous administration. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1549–51. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205228

- 17Ledingham J, Gullick N, Irving K, et al. BSR and BHPR guideline for the prescription and monitoring of non-biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Rheumatology. 2017;56:865–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kew479

- 18National Patient Safety Alerts: Towards the safer use of oral methotrexate. National Patient Safety Agency. 2004. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20180501162948mp_/http:/www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/EasySiteWeb/getresource.axd?AssetID=59985&type=full&servicetype=Attachment (accessed November 2023)

- 19Methotrexate once-weekly for autoimmune diseases: new measures to reduce risk of fatal overdose due to inadvertent daily instead of weekly dosing. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/methotrexate-once-weekly-for-autoimmune-diseases-new-measures-to-reduce-risk-of-fatal-overdose-due-to-inadvertent-daily-instead-of-weekly-dosing (accessed November 2023)

- 20Benjamin O, Goyal A, Lappin S. Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARD). National Library of Medicine. 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507863/ (accessed November 2023)

- 21Arava 20mg Tablets. Electronic medicines compendium. 2022. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4055/smpc (accessed November 2023)

- 22Hider SL, Silman A, Bunn D, et al. Comparing the long-term clinical outcome of treatment with methotrexate or sulfasalazine prescribed as the first disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2006;65:1449–55. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2005.049775

- 23Salazopyrin En-Tabs. Electronic medicines compendium. 2023. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6686/smpc (accessed November 2023)

- 24Sulfasalazine. NHS. 2023. https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sulfasalazine/ (accessed November 2023)

- 25Yusuf IH, Foot B, Lotery AJ. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists recommendations on monitoring for hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine users in the United Kingdom (2020 revision): executive summary. Eye. 2021;35:1532–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-01380-2

- 26Singh JA, Christensen R, Wells GA, et al. Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd007848

- 27Adachi Y, Yoshio-Hoshino N, Nishimoto N. The Blockade of IL-6 Signaling in Rational Drug Design. CPD. 2008;14:1217–24. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161208784246072

- 28Nishimoto N, Terao K, Mima T, et al. Mechanisms and pathologic significances in increase in serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and soluble IL-6 receptor after administration of an anti–IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Castleman disease. Blood. 2008;112:3959–64. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-05-155846

- 29Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors: new measures to reduce risks of major cardiovascular events, malignancy, venous thromboembolism, serious infections and increased mortality. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2023. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/janus-kinase-jak-inhibitors-new-measures-to-reduce-risks-of-major-cardiovascular-events-malignancy-venous-thromboembolism-serious-infections-and-increased-mortality (accessed November 2023)

- 30Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, rituximab and abatacept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis after the failure of a TNF inhibitor. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta195 (accessed November 2023)

- 31Sarilumab for moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta485 (accessed November 2023)

- 32Tofacitinib for moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta480 (accessed November 2023)

- 33Baricitinib for moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta466 (accessed November 2023)

- 34Upadacitinib for treating severe rheumatoid arthritis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta665 (accessed November 2023)

- 35Filgotinib for treating moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta676 (accessed November 2023)

- 36Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab and abatacept for treating moderate rheumatoid arthritis after conventional DMARDs have failed. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta715 (accessed November 2023)

- 37Gartlehner G, Hansen R, Jonas B, et al. The comparative efficacy and safety of biologics for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2398–408.

- 38Janke K, Biester K, Krause D, et al. Comparative effectiveness of biological medicines in rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and network meta-analysis including aggregate results from reanalysed individual patient data. BMJ. 2020;m2288. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2288

- 39Castro CT de, Queiroz MJ de, Albuquerque FC, et al. Real-world effectiveness of biological therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.927179

- 40Emery P, Pope JE, Kruger K, et al. Efficacy of Monotherapy with Biologics and JAK Inhibitors for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1535–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0757-2

- 41Henaux S, Ruyssen-Witrand A, Cantagrel A, et al. Risk of losing remission, low disease activity or radiographic progression in case of bDMARD discontinuation or tapering in rheumatoid arthritis: systematic analysis of the literature and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;77:515–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212423

- 42Verhoef LM, Tweehuysen L, Hulscher ME, et al. bDMARD Dose Reduction in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Narrative Review with Systematic Literature Search. Rheumatol Ther. 2017;4:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-017-0055-5

- 43Holroyd CR, Seth R, Bukhari M, et al. The British Society for Rheumatology biologic DMARD safety guidelines in inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology. 2018;58:e3–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key208

You might also be interested in…

Abatacept could delay rheumatoid arthritis for high-risk patients

Risk assessment for rheumatoid arthritis drug could result in fewer blood tests for patients, research suggests