CNRI / Science Photo Library

Summary box

Scleroderma is an autoimmune condition that causes fibrosis of the skin and connective tissues. Morphoea is a type of scleroderma that is limited to the skin and is typically characterised by oval or linear lesions on the trunk and limbs. En coup de sabre is a type of morphoea that affects the face and scalp and is associated with neurological disorders, including trigeminal neuralgia and epilepsy.

Scleroderma that involves the internal organs is classed as systemic sclerosis (SSc). Limited cutaneous SSc affects the hands and face, whereas diffuse cutaneous SSc can affect all areas of the body. Both limited and diffuse SSc cause thickening of affected skin and also internal connective tissues, leading to vascular disease and organ fibrosis, and can cause severe complications in the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, heart and kidneys.

[Also:

Scleroderma: management

]

Scleroderma is a rare autoimmune condition that affects connective tissue. It is characterised by chronic and progressive fibrotic changes to the skin and internal organs. Scleroderma that only affects localised areas of skin and underlying tissue is referred to as morphoea.

Morphoea is uncommon and affects less than three per 100,000 people. Onset may be associated with injury or viral infection. However, it is not entirely understood how this occurs. Two-thirds of patients affected are under 18 years old, 80% are of white ethnicity and it is three times more common in women than men[1]

.

Scleroderma that affects systemic connective tissue is classed as systemic sclerosis (SSc). SSc is characterised by widespread vascular dysfunction, tissue fibrosis and organ dysfunction. Less common forms of SSc include malignant scleroderma, which is associated with an accelerated course of disease that leads to death, and SSc sine scleroderma (SSc that occurs in the absence of skin changes), which is difficult to diagnose and not normally confirmed until after death.

SSc affects around one in 10,000 to one in 30,000 people in the UK. The most common age of onset is 30–40 years. Diffuse cutaneous SSc occurs in men and women equally, while limited cutaneous SSc is ten times more common in women. Around 1–6% of people with morphoea develop SSc[2]

. Unlike morphoea, race does not appear to be a risk factor for SSc, and there are no other identified risk factors for developing the condition[3]

.

SSc is associated with higher mortality than all other connective tissue disorders. Five-year survival is around 90% for patients with limited cutaneous SSc and around 80% for those with diffuse cutaneous SSc. Pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary fibrosis and renal crisis are the main contributors to premature death[2]

.

Cause and pathophysiology

The cause of scleroderma is poorly understood. Around 1,800 genes have been identified as being differentially expressed in affected patients, but there is a less than 2% risk of developing the condition if a first degree relative is affected, and a less than 5% risk if a twin is affected[4]

. Autoantibodies are a hallmark of connective tissue disease, and antinuclear autoantibodies are present in the plasma of at least 95% of patients with SSc[5]

. SSc-related autoantibodies include anti-topoisomerase I (anti-Scl-70) and anti-centromere 3; antinuclear autoantibodies are present in around 80% of patients with morphoea, but less than 5% of patients will test positive for anti-Scl-70 and anti-centromere 3 autoantibodies[6]

.

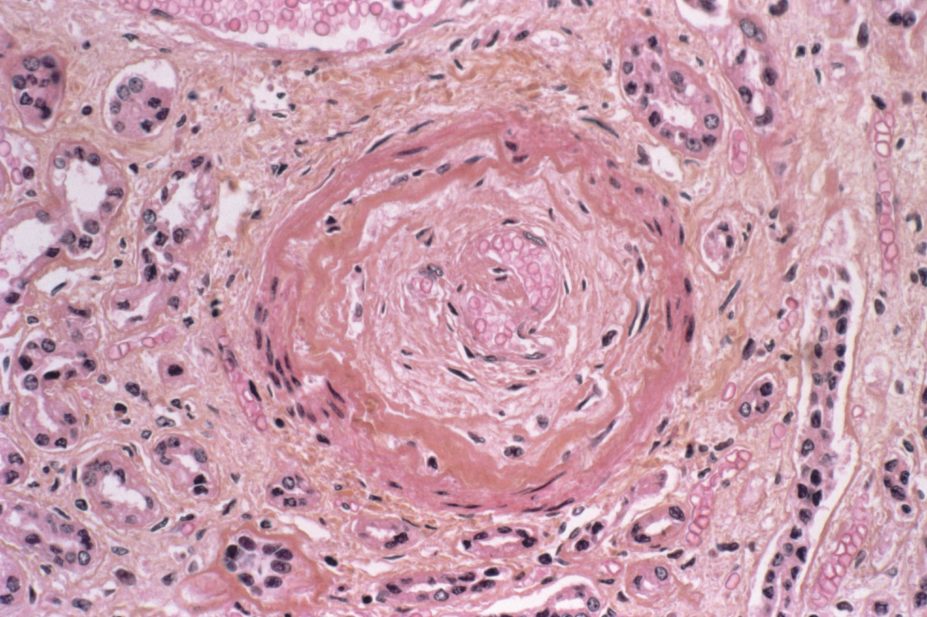

Currently, it is believed scleroderma results from an autoimmune-mediated injury to the epithelium, which causes local inflammation, the subsequent production of profibrotic cytokines and the recruitment and activation of fibroblasts. This leads to excess production of collagen causing fibrosis of affected tissues, including the narrowing of vascular beds.

Morphoea

Morphoea lesions develop insidiously and are localised to the affected skin and underlying tissue. They are typically oval or linear in shape, although they can often be poorly defined. The depth of the tissue affected is highly variable (see ‘Classification of morphoea’). Extracutaneous symptoms, such as fever, arthralgia, myalgia and fatigue, occur in around 20% of patients with morphoea.

The progression of morphoea is variable and it is hard to predict the course of the lesion. Some lesions can resolve spontaneously, while others can worsen rapidly, or resolve and then recur.

Circumscribed (plaque-like) morphoea presents as three or fewer lesions of between 1cm and 20cm in diameter on the front or back of the trunk. Superficial plaques often begin as oval patches, which gradually enlarge and become smooth, shiny, and ivory or hyperpigmented in colour. Deeper lesions involve subcutaneous fat and appear ill-defined and indurated. These lesions are typically hyperpigmented but changes in colour may be less obvious because of the depth at which they occur.

Generalised morphoea is more extensive and severe. Plaques are numerous (at least four), indurated and large (≥3cm). Lesions may appear anywhere on the body, although the hands and face are not usually affected. They vary in colour from hyperpigmented to silver.

Linear morphoea is similar to circumscribed morphoea, but the lesions are linear in shape rather than oval. The depth of involvement is also greater, and lesions can affect the deep dermis, subcutaneous fat, muscle and bone. Linear morphoea can affect (in order of likelihood) the lower limbs, the upper limbs, the face, and the anterior trunk.

Deep linear morphoea that occurs on the face or scalp is called en coup de sabre, with the depth of the lesion extending to involve the bone and meninges. En coup de sabre is associated with some neurological disorders (e.g. seizures, headaches, cranial nerve palsies involving visual changes and trigeminal neuralgia). Epilepsy is also often associated with en coup de sabre, affecting around 70% of patients with the lesion. Around one third of patients with epilepsy associated with en coup de sabre are refractory to antiepileptic therapy[7]

.

| Table 1. Classification of morphoea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Amaral et al. 2012[7] | ||||

Classification | Subtype | Characteristics of lesions | Tissue involved | Main site |

Circumscribed (plaque-like) | Superficial | Oval | Epidermis and dermis

| Trunk |

Deep | Oval | Dermis and subcutaneous tissue | Trunk | |

Linear morphoea | Trunk and limb | Linear induration | Dermis and subcutaneous tissue, may involve muscle and bone | Trunk and limbs |

Head (en coup de sabre) | Linear induration | Epidermis and dermis of frontoparietal area. May involve muscle, bone and central nervous system | Face and scalp | |

Generalised morphoea | Not applicable | More than four indurated lesions of greater than 3cm | Usually limited to the dermis and rarely involves subcutaneous tissue | Widespread (no face or hands) |

Mixed variant | Not applicable | Variable | Combination of two or more subtypes

| Variable |

Systemic sclerosis

The dermatological presentation of SSc is distinct from morphoea. SSc typically involves the face and hands in limited cutaneous SSc, and extends to other areas of the body in diffuse cutaneous SSc.

Limited cutaneous SSc affects around 60–80% of patients with SSc. It usually has a slow onset and is often preceded by Raynaud’s phenomenon (See ‘Raynaud’s phenomenon’) and inflammation and oedema in the skin of the fingers, which makes them appear thick and puffy. Sclerotic skin changes can occur in the hands, feet, face, forearms and lower legs. Tightening of the skin around the fingers can cause contracture, the permanent shortening and fixing of the joints, ÂÂand nail fold capillaries can become dilated. Tightening of the skin on the face can cause the formation of characteristic ‘beak-like’ features and a lack of wrinkles. Patients may lose the ability to make facial gestures such as smiling or frowning.

Patients may also develop secondary Sjögren syndrome (an autoimmune disease that destroys exocrine glands), dysfunction of the salivary and lacrimal exocrine glands, xerophtalmia (lack of tear production) and xerostomia (dry mouth).

| Raynaud’s phenomenon |

|---|

Raynaud’s phenomenon is the occurrence of intermittent digital ischaemia which can be precipitated by coldness or emotion. The patient’s fingers change colour from pale to blue as cyanosis develops, and appear red when warmed. Reynaud’s symptoms are idiopathic in 5–15% of cases. However, they can also be associated with:

All patients who develop symptoms of Raynaud’s phenomenon should be screened for autoimmune disease. |

Microvascular disease is common in patients with limited cutaneous SSc. Cutaneous and mucosal telangiectasias (small, dilated blood vessels at the surface of the skin) may occur and patients are at high risk of developing digital ischaemia, which can cause considerable pain and lead to ulceration and infection. Severe soft tissue infection can result in amputation of the affected fingers.

Around a fifth of patients develop calcinosis — a build-up of calcium deposits under the skin. These lesions can break through the skin causing ulceration and can become a target for soft tissue infections.

Limited cutaneous SSc was previously referred to as CREST syndrome (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, oesophageal symptoms, sclerodactyly and telangiectasia). These complications also occur in diffuse cutaneous SSc and the term is no longer used.

Diffuse cutaneous SSc affects around 30% of patients with SSc. The skin can be affected across the body and itching can be a major problem. This level of skin involvement is the main difference between diffuse and limited cutaneous SSc.

In contrast to the limited form, diffuse cutaneous SSc often progresses rapidly, causing a mixture of vascular disease and widespread inflammation of tissue, which eventually develops into fibrosis. Patients can develop severe symptoms of Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulceration as well as gastrointestinal (GI), respiratory, cardiac and renal complications.

Diagnosis

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) set the diagnostic criteria for SSc. The criteria are largely based on the presence of the clinical features of SSc and are highly sensitive and specific (both over 90%)[5]

for the disease. Thickening of the skin on the fingers that extends beyond the metacarpophalangeal joints (the knuckles at the base of the finger) alone is enough for a diagnosis of SSc to be made. If this is not present then additional items, each with varying weights, are considered (see ‘ACR and EULAR diagnostic criteria for systemic sclerosis’)[5]

.

| Table 2. ACR and EULAR diagnostic criteria for systemic sclerosis | ||

|---|---|---|

Item | Sub-item | Score |

Skin thickening of the fingers of both hands extending proximal to the metacarpophalangeal joints | Not applicable (NA) | 9 |

Skin thickening of the fingers (only count the higher score) | Sclerodactyly proximal to proximal interphalangeal joint

Puffy fingers | 4

2 |

Fingertip lesions (only count the higher score) | Fingertip pitting scars

Digital tip ulcers | 3

2 |

Telangiectasia | NA | 2 |

Abnormal nailfold capillaries | NA | 2 |

Lung involvement — pulmonary hypertension and/or interstitial lung disease | NA | 2 |

Raynaud’s phenomenon | NA | 3 |

Positive SSc-related autoantibodies (any positive) | Anti-centromere 3 Anti-topoisomerase I (anti-Scl-70) Anti-RNA polymerase III | 3 |

An overall score of ≥9 is indicative of SSc | ||

Complications of SSc

SSc can affect any part of the GI tract. The combination of fibrosis, atrophy of smooth muscle and neuropathy can impair peristalsis.

GI effects include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD), dysphagia, early satiety, bloating, nausea and vomiting. Involvement of the lower GI tract may cause pseudo-obstruction, bacterial overgrowth and alternating constipation and diarrhoea. Loss of rectal sensation may cause difficulties in evacuating the bowels, faecal urgency or incontinence. If oral intake or gastrointestinal absorption is compromised, this can cause malnutrition, vitamin deficiency and electrolyte disturbances. Chronic blood loss from dilated blood vessels in the stomach can lead to anaemia. Patients who experience upper oesophageal effects are at a greater risk of aspiration pneumonia.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) affects around 40% of patients with SSc and is equally common in both forms (yet tends to be less severe in limited cutaneous SSc)[8]

. Symptoms include shortness of breath and cough. Altered breath sounds characteristic of ILD can be heard, but may be difficult to detect in early disease; these include ‘Velcro-like’ crackles with fibrosis or ‘squawks’ due to inflammation. Patients with ILD will have a reduced forced vital capacity (FVC) with a normal (for population) forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and reduced diffusing capacity. High resolution computed tomography of the chest will identify inflammatory of fibrotic changes in ILD associated with SSc.

Many of the clinical features of ILD-associated SSc overlap with other causes of ILD, and accurate differentiation from other causes and management of respiratory care requires specialist input from an ILD service. Given the high incidence of this complication in SSc, patient care is often shared between specialist rheumatology and respiratory services.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), where there is an increase in the pulmonary artery pressure due to narrowing of the blood vessels within the lungs, affects between 10–15% of patients with SSc and is more common in those with the limited cutaneous form. Patients who have SSc and develop this complication have an estimated three-year survival rate of approximately 50% – worse than that for idiopathic PAH[1]

. The onset is often insidious but may present as shortness of breath, especially on exertion, fatigue, chest pain, palpitations and syncope. Right-sided heart failure, characterised by oedema, ascites and elevated jugular venous pressure, can occur in advanced disease.

Pulmonary hypertension may also be secondary to pulmonary fibrosis, where hypoxia causes vasoconstriction of the pulmonary arteries and the risk increases with diminishing lung volume. All patients with SSc should be screened once a year for pulmonary hypertension and referred to a specialist pulmonary hypertension service for confirmation of a diagnosis[3]

.

Cardiac complications of SSc include myocardial infarction and right-sided heart failure (secondary to respiratory disease). Myocardial fibrosis is uncommon in patients with SSc, but if present can cause arrhythmias and heart failure.

Scleroderma renal crisis is a medical emergency and can lead to renal failure. It occurs in around 12% of patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc and 2% of patients with limited cutaneous SSc. It is usually preceded by marked hypertension, as it is caused by narrowing of the small renal arteries and widespread vascular disease. Patients are usually asymptomatic in the early stages and renal function may not change until significant renal damage has occurred.

Patients with SSc should be monitored closely for possible renal crisis. This typically requires monthly blood pressure checks and three- to six-monthly assessment of renal function. Patients should be advised to seek medical advice if they begin to experience headache and blurry vision (which may be indicative of hypertension) or have a reduced urine output (more likely to occur in advanced disease).

[Also:

Scleroderma: management

]

Lloyd Mayers, ClinDipPharm, MRPharmS, is a specialist pharmacist, and Charles Sharp, BMBCh, MRCP, is a clinical fellow, both at North Bristol NHS Trust.

References

[1] Fett N & Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:217–228.

[2] Chung L, Lin J, Furst DE et al. Systemic and localized scleroderma. Clin Dermatol 2006;24:374–392.

[3] Chifflot H, Fautrel B, Sordet C et al. Incidence and prevalence of systemic sclerosis: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2008;37:223–235.

[4] Katsumoto TR, Whitfield ML & Connolly MK. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2011;6:509–537.

[5] Van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65(11):2737–2747.

[6] Leitenberger JJ, Cayce RL, Haley RW et al. Distinct autoimmune syndromes in morphea: a review of 245 adult and pediatric cases. Arch Dermatol 2009;145:545–550.

[7] Amaral TN, Peres FA, Lapa AT et al. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013;43(3):335–347.

[8] Elhai M, Meune C, Avouac J et al. Trends in mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis over 40 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:1017–1026.