Clinical Photography / Science Photo Library

Learning objectives

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Recognise the signs and symptoms of Wilson’s disease;

- Understand the causes and how the condition is diagnosed;

- Know the different treatment options and when each would be indicated.

Wilson’s disease (WD) is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disorder characterised by the accumulation of copper in various body tissues, particularly the brain, liver and corneas of the eyes[1]. It is a progressive disease and, if left untreated, may lead to liver disease, central nervous system dysfunction and death[2,3].

Overall prevalence is 1 in 30,000, and around 1 in 90 people are carriers of the defective gene[2,4]. More than 500 distinct gene mutations have been described, of which 380 have an established role in the pathogenesis of WD[3]. The risk of disease is the same for males and females.

The clinical prevalence of WD in the UK remains unknown; however, the estimated genetic prevalence of 142 per million is higher than the clinical prevalence of 15 per million reported in other European studies[5].

Without treatment, WD is fatal and is best managed by a multidisciplinary team including neurologists, hepatologists, pharmacists and dietitians[6].

The role of pharmacists is to recognise symptoms, educate patients on the consumption of low copper-containing foods and provide support on alcohol consumption to reduce liver damage.

Pharmacists should also ensure that patients are not taking any medicines that can adversely affect the liver, check for any potential interactions and monitor the pharmacological therapy, as adverse effects of copper chelation can potentially worsen symptoms[6].

Causes

WD is caused by a mutation in the ATP7B gene on chromosome 13. The ATP7B gene is responsible for controlling the transport of copper from intracellular proteins into secretory pathways for excretion into bile and synthesis of ceruloplasmin (a protein that binds copper in the bloodstream)[7].

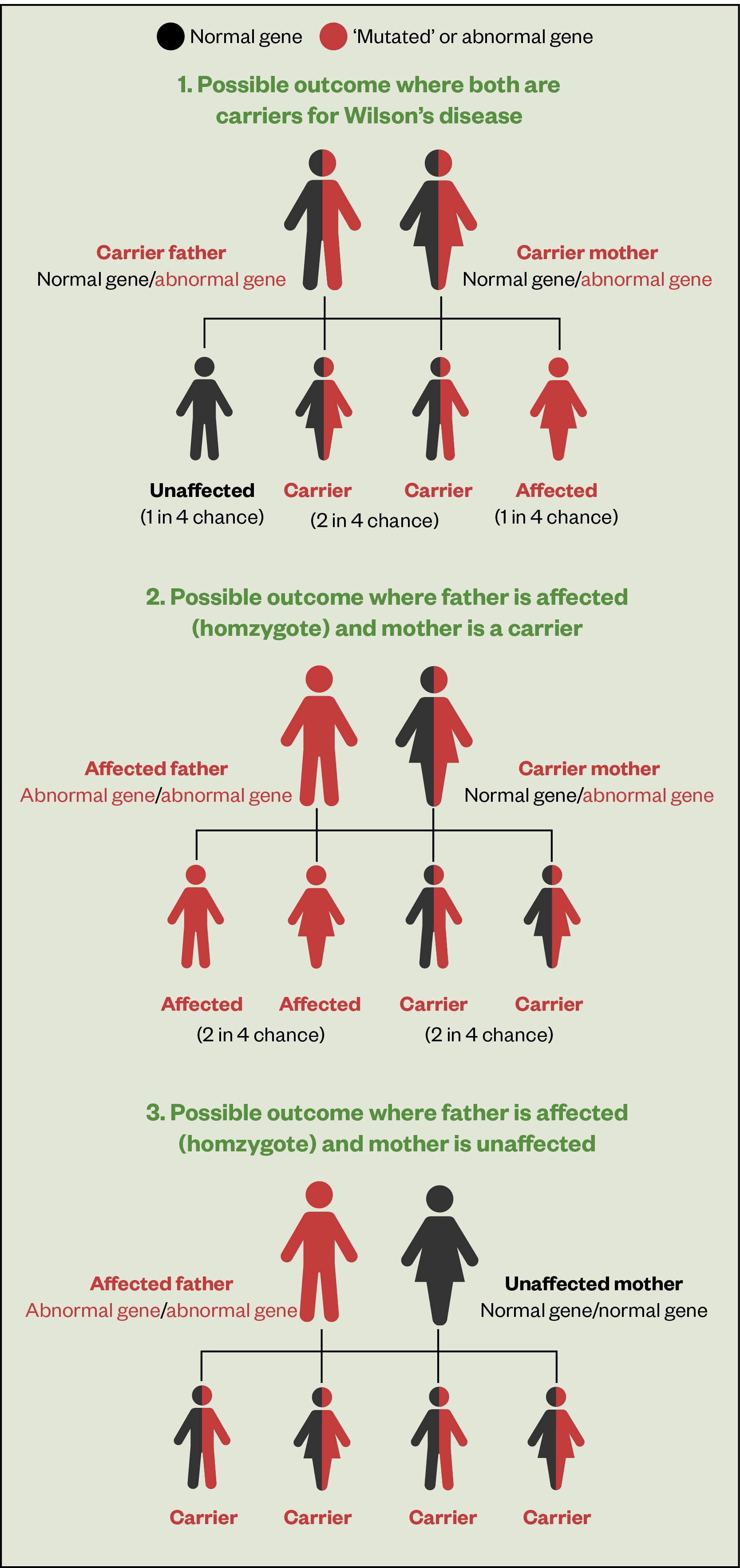

As WD is an autosomal recessive disorder, an individual must inherit two copies of the mutated ATP7B gene, one from each parent, both of whom are usually carriers (see Figure 1)[8]. If an individual inherits one normal gene and one mutated gene, they will be a carrier but usually will not show any symptoms.

The risk of two carriers passing the abnormal gene to an affected child is 25%; to a child who is a carrier is 50% and to a child with normal genes is 25%[3].

Signs and symptoms

Although the genetic mutation is present at birth, it may take many years for copper to build up to levels where symptoms develop. WD commonly presents in a younger population — mean age 11–25 years — but can present at any age[9].

The main sites of copper accumulation are the liver and brain, leading to liver disease and neurological symptoms, which are the main features that lead to diagnosis[10].

Liver symptoms

Initial presenting symptoms of liver disease can range from asymptomatic with biochemical abnormalities to cirrhosis if left untreated.

Common signs of liver disease include yellow discolouration (jaundice) of the skin, membranes lining the eye and mucosal membranes, swelling of the legs (oedema) and abdomen (ascites), oesophageal varices and excessive fatigue[3].

Neurological symptoms

If copper deposits in the brain, it can cause various neurological signs including tremors, ataxia, dystonia, headaches and seizures[3,11,12]. If left untreated, neurological symptoms can lead to severe muscle weakness, rigidness and dementia[11].

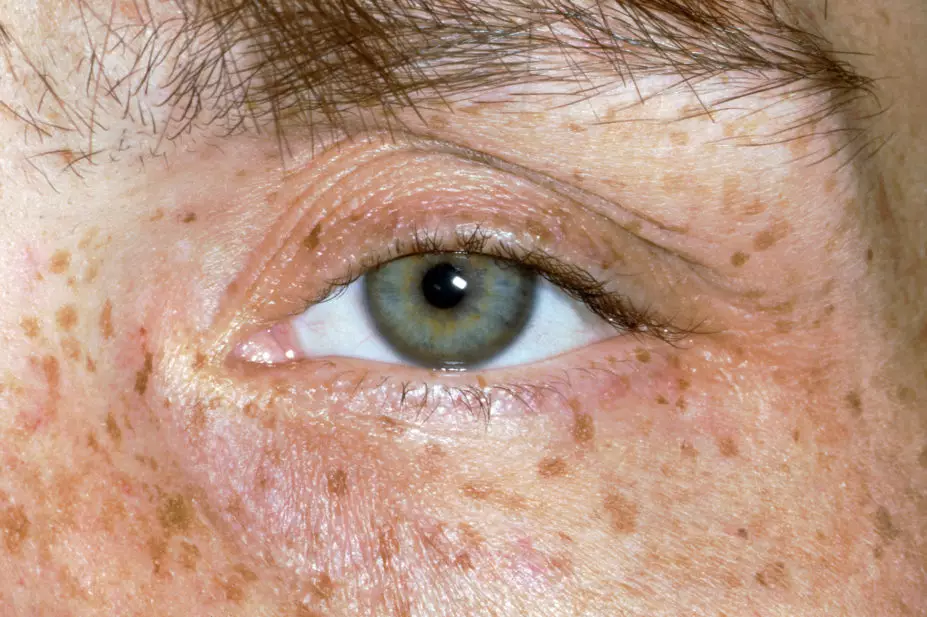

Around 95% of patients with neurological symptoms have Kayser–Fleischer (KF) rings, dark golden or brown rings that appear to encircle the iris of the eye (see Figure 2) and are caused by copper deposition in the descemet’s membrane of the cornea[13].

Source: Clinical Photography / Science Photo Library

In addition, psychological problems — such as depression, mood swings and personality changes — are seen in some patients[11].

Other

Renal disease symptoms — such as kidney stones, premature arthritis, anaemia, heart disease, pancreatitis — and other joint and bone involvement, including osteoporosis, may be present[4,11]. In female patients, menstrual problems and issues with repeated miscarriage have been reported[11].

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is important to avoid the possibility of permanent neurological dysfunction and serious liver disease. If a patient presents with any of the early symptoms of WD outlined above, pharmacists should refer them to secondary care for urgent blood tests to determine ceruloplasmin levels.

In the initial stages of the disease, patients can also be referred to an optometrist to perform a slit lamp examination to determine the presence of KF rings; however, as the disease progresses these can often be seen with the naked eye, particularly when the iris is lightly pigmented and there is severe copper overload[13].

Hepatologists, neurologists, ophthalmologists and nephrologists, usually in secondary care, will likely be involved in confirming the diagnosis, usually made when a combination of KF rings and a low serum ceruloplasmin (<0.1g/L) level is present.

Other tests include a 24-hour urinary copper (>1.6micromol/24 hours), serum ‘free’ copper (12.0–25.0 micromol/L), hepatic copper (>4micromol/g dry weight) and other liver function tests (e.g. serum aminotransferase)[3].

A liver biopsy is only required if the clinical signs and non-invasive tests do not confirm diagnosis of WD[2].

Currently, diagnosis remains laboratory and patient factor-based; however, there is an emerging role for genetic testing in patient and sibling diagnosis. Comprehensive molecular genetic studies use DNA from blood cells to search for patterns for analysis to establish if a full sibling of the affected patient is a carrier of the WD gene[4].

Figure 1 outlines the potential outcomes of familial screening on first-degree relatives (siblings, parents and offspring) of the patient[3].

Treatment

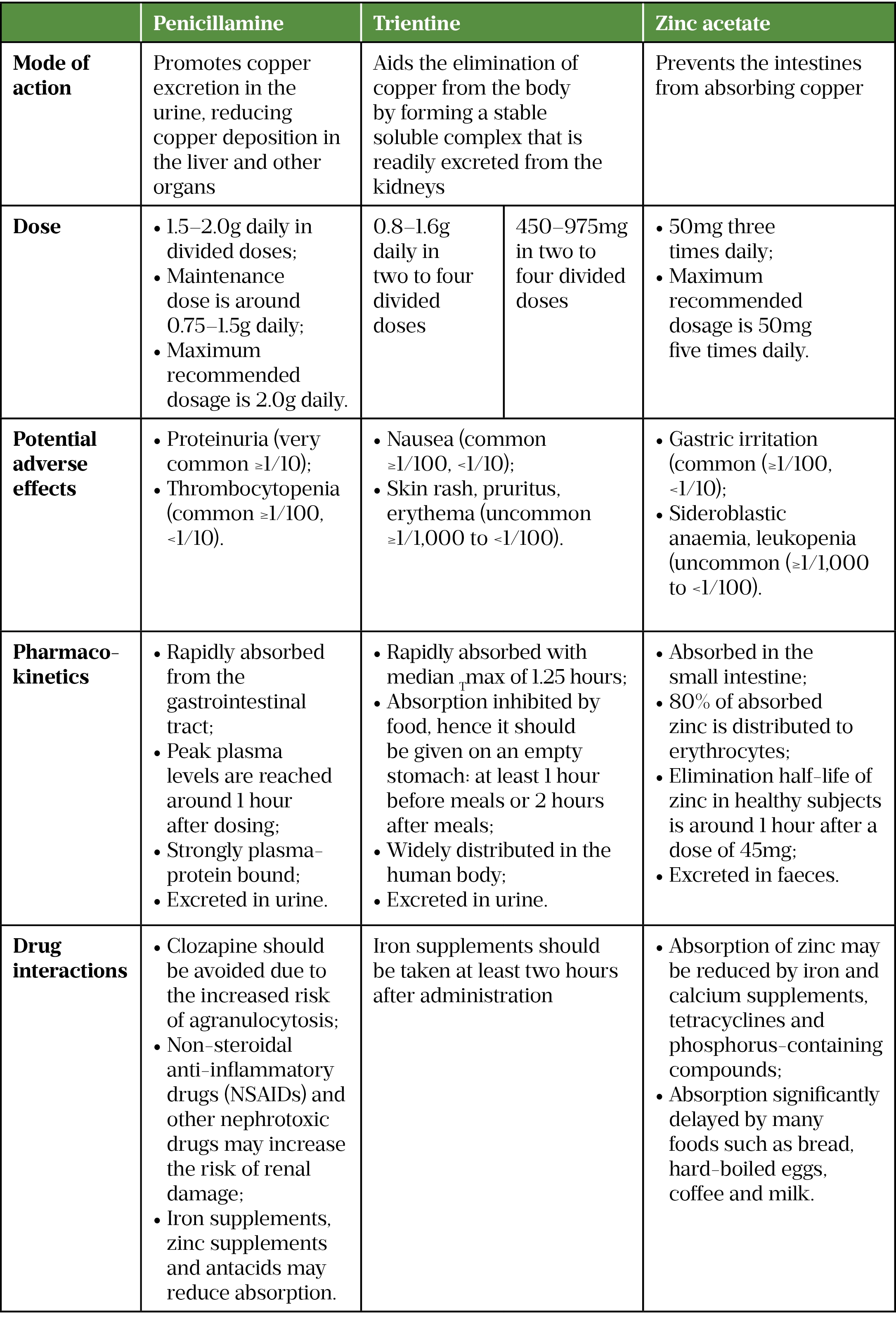

Improving symptoms and preventing organ damage are the main aims of treatment for WD; however, this often means patients require lifelong treatment, particularly as stopping treatment may cause acute liver complications[14]. Treatment includes medicines that remove copper such as chelating agents (e.g. penicillamine and trientine) and zinc, which prevent intestines from absorbing copper (see Table)[14–17].

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines recommend that all symptomatic patients with WD should receive a chelating agent and zinc should not be used as monotherapy[3]. Penicillamine is generally used first-line to treat symptomatic patients in the UK; however, it should be noted that it is not tolerated in around one third of patients. Trientine is usually recommended second-line in patients intolerant of penicillamine (see Table)[3,14–17]. Zinc salts can be used; however, there is limited evidence that zinc is effective in preventing the progression of liver disease when used alone[3].

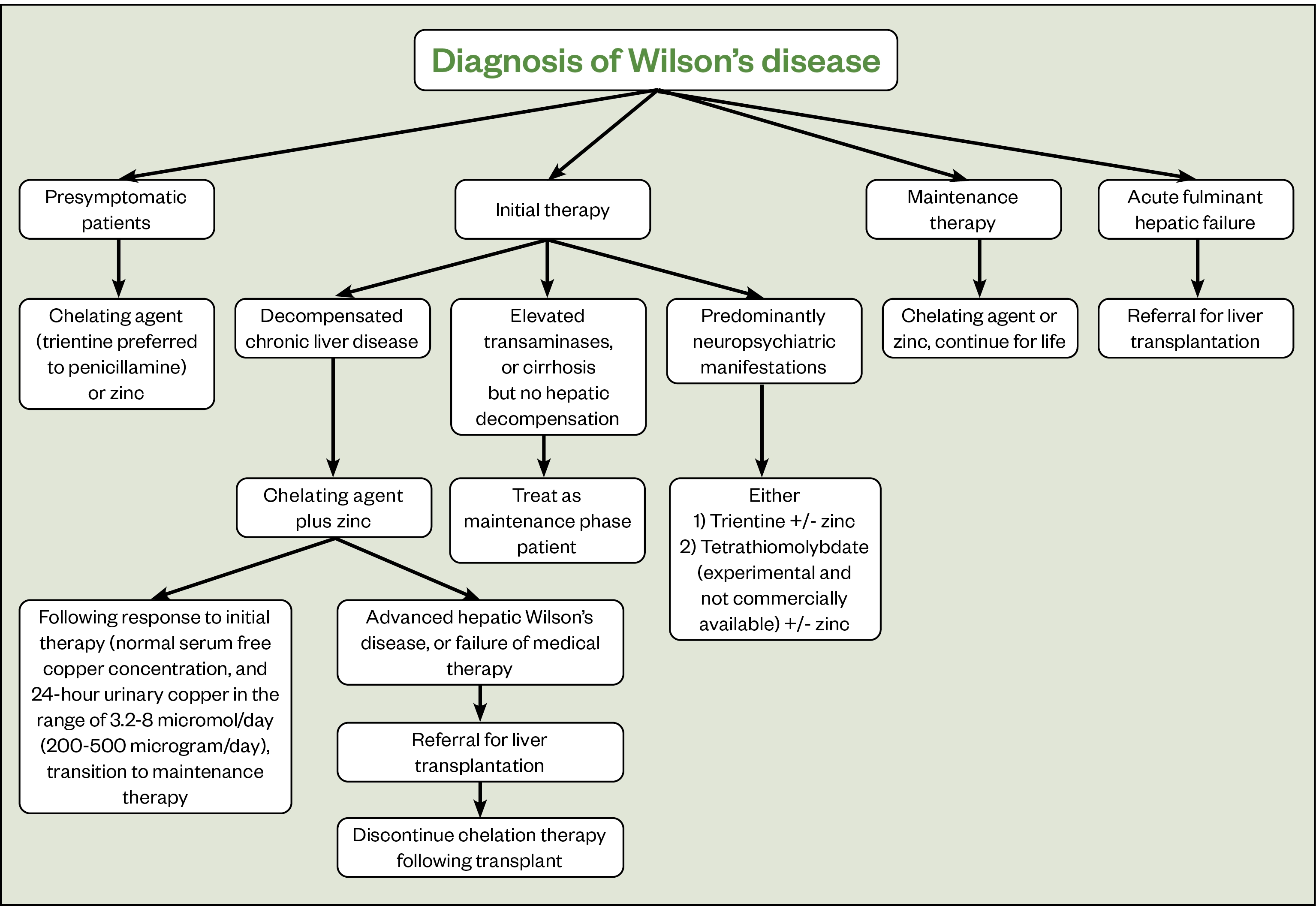

Figure 3 outlines the treatment recommendations for the management of WD[18]. Pharmacists should support patients to manage their condition, providing advice on their medicines and by signposting to useful resources published by organisations, such as the British Liver Trust.

Long-term management

Dietary and lifestyle advice

Moderate consumption of foods with high concentrations of copper — such as chocolate, shellfish, nuts, liver and soy — as well as establishing a water purifying system to avoid drinking water that may have flowed through copper pipes should be advised[18]. In addition, the accumulation of copper in the liver is known to produce oxidative stress-related damage.

Over-the-counter supplementation of antioxidants (e.g. vitamin E) may be beneficial; however, no well-controlled studies have been performed to provide an evidence-based recommendation[18].

Community pharmacists can also advise patients on how to reduce alcohol consumption and ensure they are vaccinated against diseases, such as viral hepatitis, to reduce further liver damage[18].

It is important for patients to maintain muscle function and effectively manage occurrences of contractures. Community pharmacists can provide information on muscle strengthening and flexibility exercises and can signpost patients to local physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Prognosis

Patients with WD have an excellent prognosis, provided they remain compliant with treatment and adhere to medicine regimens.

Patients who discontinue treatment are at a high risk of fulminant hepatic failure; therefore, it is recommended to continue life-long treatment[18]. Patients with neurological features should begin to show clinical improvement six months after initiation of anti-copper therapy[18].

Pharmacists should be aware of and be able to confidently identify symptoms of chronic liver disease (e.g. ascites and encephalopathy) and, if required, can support patients by ensuring diuretic therapy is optimised, infection prophylaxis is initiated and salt is restricted through dietary adjustments.

- 1El-Youssef M. Wilson Disease. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2003;78:1126–36. doi:10.4065/78.9.1126

- 2Cao C, Colangelo T, Dhanekula RK, et al. A Rare Case of Wilson Disease in a 72-Year-Old Patient. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6:e00024. doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000024

- 3EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Wilson’s disease. European Association for the Study of the Liver. https://www.journal-of-hepatology.eu/article/S0168-8278(11)00812-9/fulltext (accessed May 2022).

- 4Wilson Disease. National Organization for Rare Disorders. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/wilson-disease/ (accessed May 2022).

- 5Wijayasiri P, Hayre J, Nicholson ES, et al. Estimating the clinical prevalence of Wilson’s disease in the UK. JHEP Reports. 2021;3:100329. doi:10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100329

- 6Chaudhry H, Anilkumar A. statpearls. Published Online First: 11 August 2021.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441990/

- 7Sapuppo A, Pavone P, Praticò AD, et al. Genotype-phenotype variable correlation in Wilson disease: clinical history of two sisters with the similar genotype. BMC Med Genet. 2020;21. doi:10.1186/s12881-020-01062-6

- 8Wilson’s disease. British Liver Trust. https://britishlivertrust.org.uk/information-and-support/living-with-a-liver-condition/liver-conditions/wilsons-disease/ (accessed May 2022).

- 9Rodriguez-Castro KI. Wilson’s disease: A review of what we have learned. WJH. 2015;7:2859. doi:10.4254/wjh.v7.i29.2859

- 10Ala A, Walker AP, Ashkan K, et al. Wilson’s disease. The Lancet. 2007;369:397–408. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60196-2

- 11Knott L. Wilson’s Disease. Patient. 2021.https://patient.info/digestive-health/abnormal-liver-function-tests-leaflet/wilsons-disease (accessed May 2022).

- 12Mahajan R, Zachariah U. Wing-Beating Tremor. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:e1. doi:10.1056/nejmicm1312190

- 13Pandey N, John S. statpearls. Published Online First: 13 January 2022.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459187/

- 14Trientine for the treatment of Wilson’s disease (adults). King’s College Hospital 1234.

- 15Penicillamine 250 mg film-coated tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2713/smpc#gref (accessed May 2022).

- 16Syprine® (trientine hydrochloride) Capsules. Bausch Health. 2020.https://www.bauschhealth.com/Portals/25/Pdf/PI/Syprine-PI.pdf (accessed May 2022).

- 17Wilzin 25mg hard capsules. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6245/smpc#gref (accessed May 2022).

- 18Kathawala M, Hirschfield GM. Insights into the management of Wilson’s disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:889–905. doi:10.1177/1756283×17731520