Shutterstock

Women who use hormonal contraception have an increased risk of depression, according to researchers in Denmark.

The authors, based at the University of Copenhagen, found that the chances of being treated with an antidepressant for the first time increases the longer a hormonal contraceptive has been used.

“Use of hormonal contraceptives was associated with subsequent antidepressant use and first diagnosis of depression at a psychiatric hospital among women living in Denmark,” they say.

“Adolescents seemed more vulnerable to this risk than women 20–34 years old. Further studies are warranted to examine depression as a potential adverse effect of hormonal contraceptive use.”

The researchers, reporting in

JAMA Psychiatry (online, 28 September 2016)[1]

, say their findings suggest that healthcare professionals should be made aware of the risk of depression, which they describe as “this relatively hitherto unnoticed adverse effect of hormonal contraception”.

The authors looked at data from more than 1 million women aged between 15 and 34 years from the Danish National Prescription Register and the Psychiatric Central Research Register. The patients were tracked from 2000–2013 for their first use of an antidepressant or for a diagnosis of depression, either as a hospital outpatient or inpatient.

The researchers compared the results of women who were using or had used hormonal contraceptives compared with ‘non-users’, defined as women who had never used them or were previous users. The average follow-up time was 6.4 years.

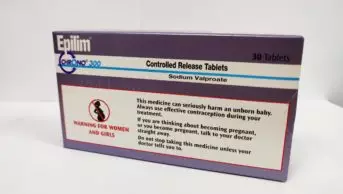

The researchers found that the likelihood of being prescribed an antidepressant for the first time or being diagnosed with depression at a psychiatric hospital were higher in young women aged between 15 and 19 years who were taking hormonal contraceptives. But the likelihood of depression decreased with age for patients taking the most commonly used products, including combined oral contraceptives and progestogen-only pills.

The researchers discovered that users of combined oral contraceptives had a rate ratio (RR) of first use of an antidepressant of 1.23 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.22-1.25), compared with non-users, who had a reference RR of 1.

For users of progestin-only pills, the RR was 1.30 (95% CI 1.27–1.40); for users of a patch (norelgestromin) it was 2.0 (95% CI 1.76–2.18); for users of a vaginal ring (etonogestrel) the RR was 1.6 (95% CI 1.55-1.69); and for users of a levonorgestrel intrauterine system the RR was 1.4 (95% CI 1.31-1.42).

The researchers found similar or slightly lower estimates when they looked at the RRs for hospital diagnosis of depression.

When they focused only on the results for young women aged between 15 and 19 years, the figures revealed “notably higher” RRs of first use of antidepressants and first diagnosis of depression.

In this age group, users of the combined oral contraceptives had a RR of first use of an antidepressant of 1.8 (95% CI 1.75-1.84), which rose to a RR of 2.2 (95% CI 1.99-2.52) for progestin-only pills.

Jane Bass, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s spokesperson on women’s health, says previous studies have produced conflicting evidence.

“This study was able to access records for over 1 million women for almost 20 years and so adds a significant patient cohort to the data already available.”

However, she thinks the findings “are not enough to change practice”.

“Further studies are needed on a population basis in other healthcare settings and to elicit the mechanisms by which hormonal contraceptives may trigger depressive moods in the hope that the risk can be minimised in future,” she adds.

“The benefits of hormonal contraceptives in reducing the risks of an unplanned pregnancy outweigh the side effects for the majority of women.”

Bass also points out that depression and depressive mood are already listed in the UK as potential common side effects for oral and non-oral hormonal contraceptives.

Natika Halil, chief executive of the sexual health charity the FPA, says: “We know many women are using hormonal contraception without problems, and we wouldn’t want to see women worried by this study to suddenly stop using their hormonal method, as this will leave them at risk of unplanned pregnancy.”

She says that there are alternatives to hormonal contraception and that women should discuss their options and any unwanted side effects with their health professional.

Anatole Menon-Johansson, medical director at Brook, the sexual health and well-being charity for young people, says the findings are worth further exploration, but adds: “The paper assumes that hormonal contraception is the direct cause of depression and in fact there are many other important confounders which are not considered in this research.”

She says: “We can assume that the majority of women surveyed are in heterosexual relationships, and many of them will have new partners. The study does not account for the other ways in which the pressures of relationships can affect women’s mental health such as cohabiting, alcohol, children and domestic violence.”

References

[1] Skovlund C W, Mørch L S, Kessing L V et al. Association of hormonal contraception with depression. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2387