Shutterstock.com

The worldwide web is an integral part of our lives, but concerns have recently been raised about people accessing treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) online.

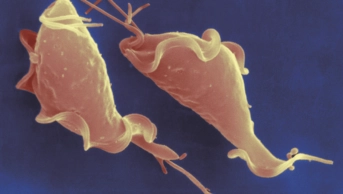

The internet has undeniably had a positive impact on the UK sexual health scene, providing increased access to STI testing, accurate information on sexual well-being and much needed signposting to clinics and support services. However, an investigation initiated by Faye Kirkland, GP and journalist, has shown that some online services are not offering the correct treatments for STIs, namely gonorrhoea. “Gonorrhoea is the second most common STI in the UK and requires both an injection and tablets to treat it effectively,” says Kirkland. “This combination can only be accessed at a sexual health clinic or GP.”

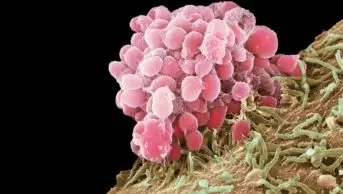

Growing gonorrhoea resistance has been of global concern for many years and, in 2000, Public Health England (PHE) introduced the Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (GRASP) to monitor trends in gonococcal resistance in England and Wales. Data collected demonstrate that gonorrhoea is on the increase and PHE reports that the bacteria has “successively developed resistance to a range of antibiotics that have been used to treat the disease”. As a result, the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) modified its national guidelines in 2011 to recommend the more aggressive dual therapy with injectable ceftriaxone and oral azithromycin, which appears to have helped slow resistance development [PDF]. Online STI services are offering only tablets for the infection though, which may sub-optimally treat it, result in transmission to others and may contribute to further resistance.

Moreover, effective STI management does not just mean medication. You need to know which infections require treatment by getting the right tests done. Some online services are providing medicines without confirmation of infection. Antibiotics must be prescribed safely, with respect to medical conditions and allergies. Sexual partner notification is necessary. Also, gonorrhoea requires a “test of cure” after two weeks to ensure elimination. Finally, opportunities for confidential, non-judgemental discussion with a trained professional are an important component of sexual healthcare.

So how can this situation be managed? Awareness is important and, according to BBC5 Live Investigates, Kirkland’s investigation has since prompted a number of online services, some fronted by celebrity campaigns, to amend their website advice to include the points above.

Reasons why the public are opting to access their sexual healthcare in this way must also be addressed: embarrassment, reduced access to care and lack of education all contribute to it and are understandable. In light of this, the government must ensure adequate sexual health education for young people, adequate provision of sexual healthcare for the public and appropriate governance of the lucrative trend of online prescribing.

The challenges are evident. But to limit the ongoing risk of gonococcal treatment failure and with the prospect of no effective treatment for an infection that affects around 30,000 people in the UK each year, this issue must be taken seriously.

Verity Sullivan is a specialist registrar in sexual health and HIV at King’s College Hospital, London.