Abstract

Asthma is a heterogenous condition and affects more than 330 million people worldwide and 8 million people in the UK. Patients with severe asthma account for around 3.6% of all asthma patients, equating to approximately 200,000 patients in the UK.

With the introduction of biologic therapies, severe asthma has entered the precision medicine era; however, while it is estimated that more than 60,000 patients in England would benefit from an asthma biologic, data suggest that only 11,000 of these patients receive one. This seemingly low uptake of a potentially transformative therapy led the NHS England Accelerated Access Collaborative (AAC) Rapid Uptake Products programme to select asthma biologic treatment as one of their four therapeutic interventions to investigate and support. The programme began in September 2020 and was a collaboration among clinical experts, the Oxford Academic Health Science Network (AHSN) and NHS England AAC. The programme team identified 11 priority areas of care to explore, which included more effective identification of people who are potentially eligible for NHS-funded biologics; upskilling healthcare professionals to deliver better care; and streamlining access to appropriate expert care.

This article provides an overview of the evolution in asthma management over the past decade, the journey ahead to implement meaningful change and the vital role of pharmacists in delivering better outcomes for adults with asthma.

Key words: Uncontrolled asthma, severe asthma, asthma biologics, difficult to treat asthma, oral corticosteroids, pharmacist.

Introduction

Asthma is a disease characterised by chronic airway inflammation and hyper-responsiveness that can vary over time and in intensity. There are many respiratory symptoms — such as wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough — and people may also exhibit variable expiratory airflow limitation[1]. Owing to its heterogenous nature, asthma management requires regular reviews and interventions appropriately tailored to the patient’s current level of severity[2].

Several terms are used interchangeably when describing asthma severity; however, understanding and using the correct terminology is essential for appropriate management. ‘Uncontrolled’ asthma results from poor symptom control and causes frequent exacerbations (≥2 per year) requiring oral corticosteroids (OCS) or ≥1 hospitalisation per year[1]. The definition of ‘severe’ asthma has changed over time but is increasingly being regarded as a distinct disease entity owing to the identification of a different underlying disease pathology. The most widely accepted definition of severe asthma comes from the European Respiratory Society (ERS)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) guideline[3]. When a diagnosis of asthma is confirmed and comorbidities addressed, severe asthma is defined as “asthma that requires treatment with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids plus a second controller (and/or systemic corticosteroids) to prevent it from becoming ‘uncontrolled’ or which remains ‘uncontrolled’ despite this therapy”[3]. The same guidelines define ‘Difficult-to-treat’ asthma as disease that could be uncontrolled owing to inadequate or inappropriate treatment, poor adherence to therapy, suboptimal inhaler technique, environmental exposures (e.g. allergens, tobacco smoke, cold temperatures) or untreated comorbidities[3]. Understanding the difference between these definitions helps healthcare professionals manage their patients appropriately and refer for specialist advice where needed in a timely way. Truly refractory severe asthma (i.e. asthma that remains persistently symptomatic despite pharmacological intervention) should be managed by specialist severe asthma centres when biological therapies may be indicated[4].

Patients with poor control of asthma symptoms often face substantial disease burden. It heavily impacts their quality of life, healthcare utilisation and society through loss of productivity in the workplace. In the UK, asthma affects more than 8 million people (around 12% of the population) and accounts for 2–3% of primary care consultations and 60,000 hospital admissions per year[5]. Figures reporting the numbers of patients with severe asthma vary, but data from Asthma UK suggest it to be 3.6% of all asthma patients in the UK, equating to around 200,000 people[6]. The annual healthcare cost of uncontrolled severe asthma has been shown to be four times higher than the general asthma population (£861 versus £222, respectively), which is primarily owing to emergency healthcare utilisation, medication use and management of oral steroid-related adverse events[7].

With the introduction of biological therapies, severe asthma has entered the precision medicine era and this is driving clinical ambition towards disease remission[8]. Despite improved understanding of complex asthma pathophysiology, phenotypes and new biological therapies, management of severe asthma remains suboptimal. Research by Asthma and Lung UK revealed that three in four people with suspected severe asthma who are potentially eligible for biologics in England are not being referred to specialist centres and are therefore unable to access these treatments[9]. A combination of a lack of awareness of available new therapies and system barriers (such as long waiting times and long distances to travel to specialist centres) is reported to have contributed to this low referral rate[10]. Recognition of these challenges has led to the creation of tools and resources to mitigate them. This article describes these tools and highlights the vital role for pharmacists in identifying and managing patients with uncontrolled or severe asthma, which will ultimately improve patient outcomes by facilitating access to these potentially life-changing treatments.

Standard asthma management strategies

Several national asthma guidelines are used by clinicians in the UK[4,11]. These are the results of collaboration between the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), as well as guidance published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)[4,11]. Most locally developed guidelines will be based on these. However, the lack of a uniform approach to asthma diagnosis and management has generated criticism, leading NICE, SIGN and BTS to develop a single joint guideline, which should be published in late 2024. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) is an international group of experts that has created a strategy document to guide asthma care[1]. Updated annually, it provides up-to-date advice recommendations and has led the way in transforming the approach to asthma management[1].

Short-acting B2-agonist (SABA) overuse and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) underuse have been found to be associated with more frequent asthma exacerbations and higher mortality[12]. For this reason, SABA monotherapy has been eliminated from asthma management pathways and should not be prescribed without ICS-containing therapy in asthma. GINA has also introduced a ‘SABA-free’ treatment track, which recommends regular ICS-containing therapy, but the ‘as required’ component of management is low-dose ICS-formoterol, not a SABA. This ‘anti-inflammatory reliever’ regimen has been developed to provide the benefit of supplemental ICS, while the formoterol offers rapid onset bronchodilation (comparable to SABA) over an extended duration of action[1].

The addition of long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) to ICS/LABA therapy has been shown to modestly improve lung function and reduce exacerbation frequency in moderate to severe asthma compared with stepping up to some high-dose ICS/LABA combinations[13]. A trial of a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA [e.g. montelukast]) may improve symptom control, but healthcare professionals should have a low threshold to stop the LTRA if it is not effective (few adult asthma phenotypes respond to it, primarily those with exercise induced asthma and/or allergic rhinitis)[14]. It is thought that in the future, pharmacogenetics may help select patients likely to respond to a LTRA[13].

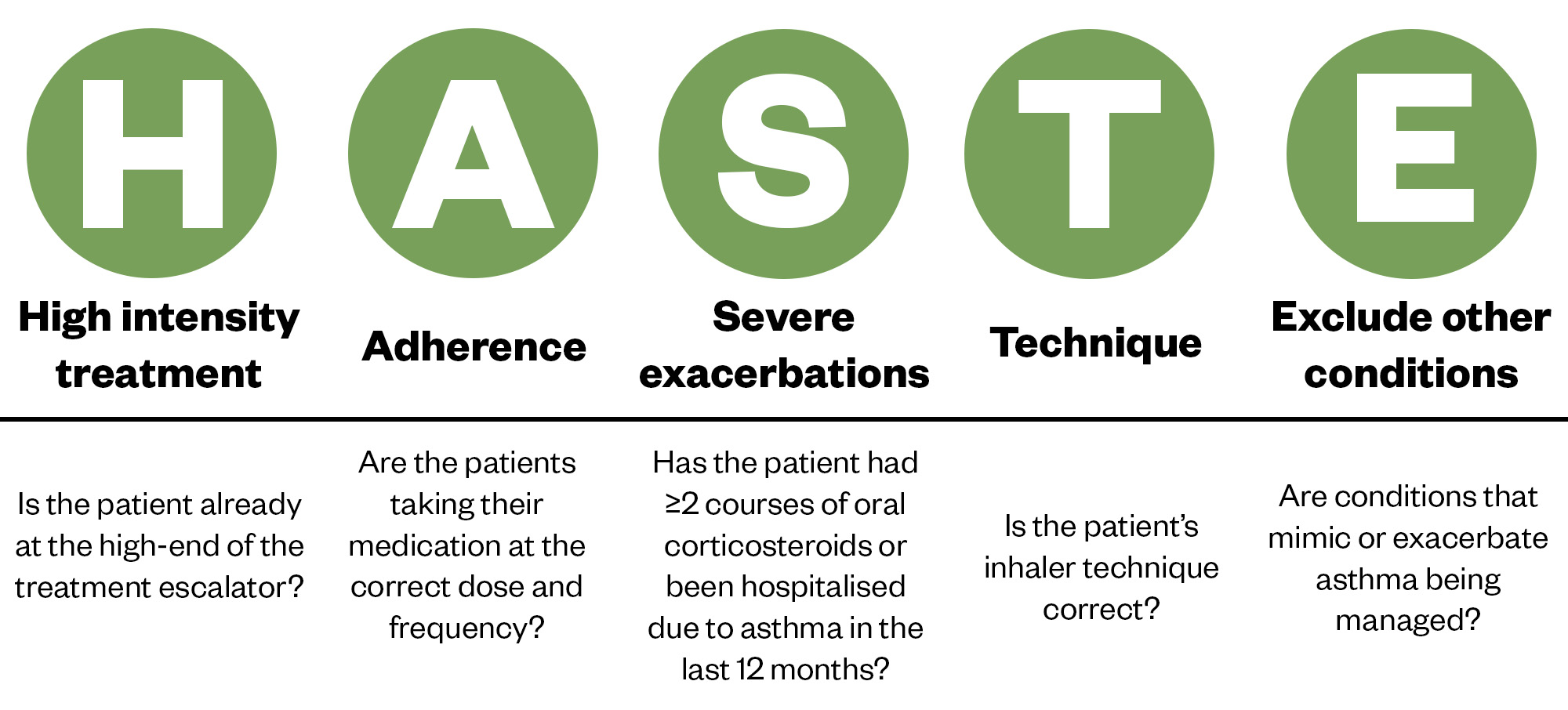

In the UK, registry data show that patients with severe asthma have had a median of four exacerbations per year when they are referred into a severe asthma centre[15]. Although OCS can be lifesaving when used to treat an asthma exacerbation, they can have devastating long-term side effects, including skin thinning, diabetes, osteoporosis, mood disturbances, cardiovascular disease, infection, anxiety and depression. Frequent or prolonged OCS use can cause adrenal insufficiency, so there is an urgent need for patients and healthcare professionals to better understand when oral steroids are appropriate[16,17]. OCS should no longer be considered a safe and inevitable consequence of having an airways disease such as asthma[18]. If patients experience debilitating asthma symptoms and/or have an exacerbation, healthcare professionals can use the HASTE tool to optimise care (see Figure 1)[19]. This has been designed to identify potentially useful interventions and, if the answers to all the HASTE questions are yes yet the asthma remains uncontrolled, a referral to secondary care should be considered.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

The Accelerated Access Collaborative, Academic Health Science Network and the Asthma Biologics national programme (adults)

Six biologic therapies — omalizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab, benralizumab, dupilumab and tezepelumab — are currently licensed for adult patients and have National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) approval for use in severe asthma in England[20–25]. Despite this, uptake has been slow. It is estimated that in England, over 60,000 patients with severe asthma would benefit from an asthma biologic[26]. However, prescribing data suggest that only around 11,000 of these patients are being treated with one (NHS England Blueteq data 2021)[27]. For this reason, asthma biologic treatment was selected as part of the NHS England AAC Rapid Uptake Products (RUP) programme in September 2020[28,29]. This programme was aimed to improve outcomes for people with asthma by reducing inequalities and increasing access to biologics for all eligible adult patients.

In July 2020, a panel of experts was assembled to agree priorities for the programme (see Table 1[27]). This included the programme clinical champions for respiratory medicine (a consultant asthma physician, a consultant respiratory pharmacist and an advanced nurse practitioner), representatives from NHS England, the AHSN, Asthma and Lung UK, NICE, Primary Care Respiratory Society, the Association of Respiratory Nurses, and Martin Allen, the national clinical director for respiratory medicine[27].

The programme was delivered over two years, from April 2021 to March 2023, and resulted in the creation of many useful support tools and resources for the healthcare workforce and patients, as seen in Table 2[26]. These are available via the Asthma Biologics Toolkit hosted on the Oxford AHSN website[26]. The self-directed e-learning module on ICS adherence is being adapted by the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education (CPPE) (due April 2024).

The programme had a demonstrable impact on clinical outcomes. Two key indicators of success were the additional 4,695 eligible patients initiated on an asthma biologic and a reduction in OCS exposure for many patients[30]. At the end of the programme, there were 3,195 fewer respiratory patients across England dispensed more than 3g of oral prednisolone annually[30]. It should be noted that these outcomes were achieved at a time when COVID-19 was having a significant impact on healthcare services.

Identification of uncontrolled asthma in primary care including the use of an innovative tool (SPECTRA)

A 2021 NICE adoption scoping report and a national benchmarking exercise that took place in March 2022 revealed that the identification of potential severe asthma cases in primary care was variable and, in most cases, only following patient crisis (e.g. following an admission to hospital or an exacerbation requiring OCS)[18,31]. The benchmarking exercise also revealed that over a third of GP practices in England reported not having a method to identify high-risk patients, as shown in Figure 2. Responses were received from 63 GP practices[31].

A 2020 review of primary care databases (OPCRD) showed that less than 30% of individuals with potentially severe asthma were referred to, or known to, secondary care[32]. These data indicated a significant gap and the need to proactively identify people that potentially have severe asthma. This challenge and opportunity led the AAC RUP project team to collaborate with industry partners (Pharmaceutical industry and Oberoi Consulting) to develop a tool to identify high-risk patients within GP practices and support their subsequent referral into secondary or tertiary care. The tool, ‘SPECTRA‘ (identification of suspected severe asthma in adults), acts to risk stratify patients suspected of having severe asthma based on number of OCS treated exacerbations, SABA inhaler use and poor symptom control[33]. It can be imported into GP practice software systems free of charge[33]. As of March 2023, unpublished data from SPECTRA showed that 497 GP practices had registered for SPECTRA and 239 GP practices had run the searches.

Structured asthma medication review template

The AAC project team worked with a pharmacy clinical subgroup, airways pharmacists from Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and Oberoi Consulting to create a structured asthma medication review template[34]. It can be imported free of charge into GP prescribing systems (EMISweb and SystmOne) and guides the clinician through:

- Confirmation of inhaled corticosteroid adherence using the Medicines Possession Ratio calculation;

- Identification of the potential reasons for inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) non-adherence (e.g. using the ‘Test of Adherence to Inhalers’ (TAI) questionnaire);

- Strategies to optimise inhaler use (good technique, maximise ICS use, minimise SABA use);

- How to make appropriate low carbon inhaler choices;

- Quantification and understanding of OCS exposure, including when to refer[34].

The place of biologic therapy in asthma management

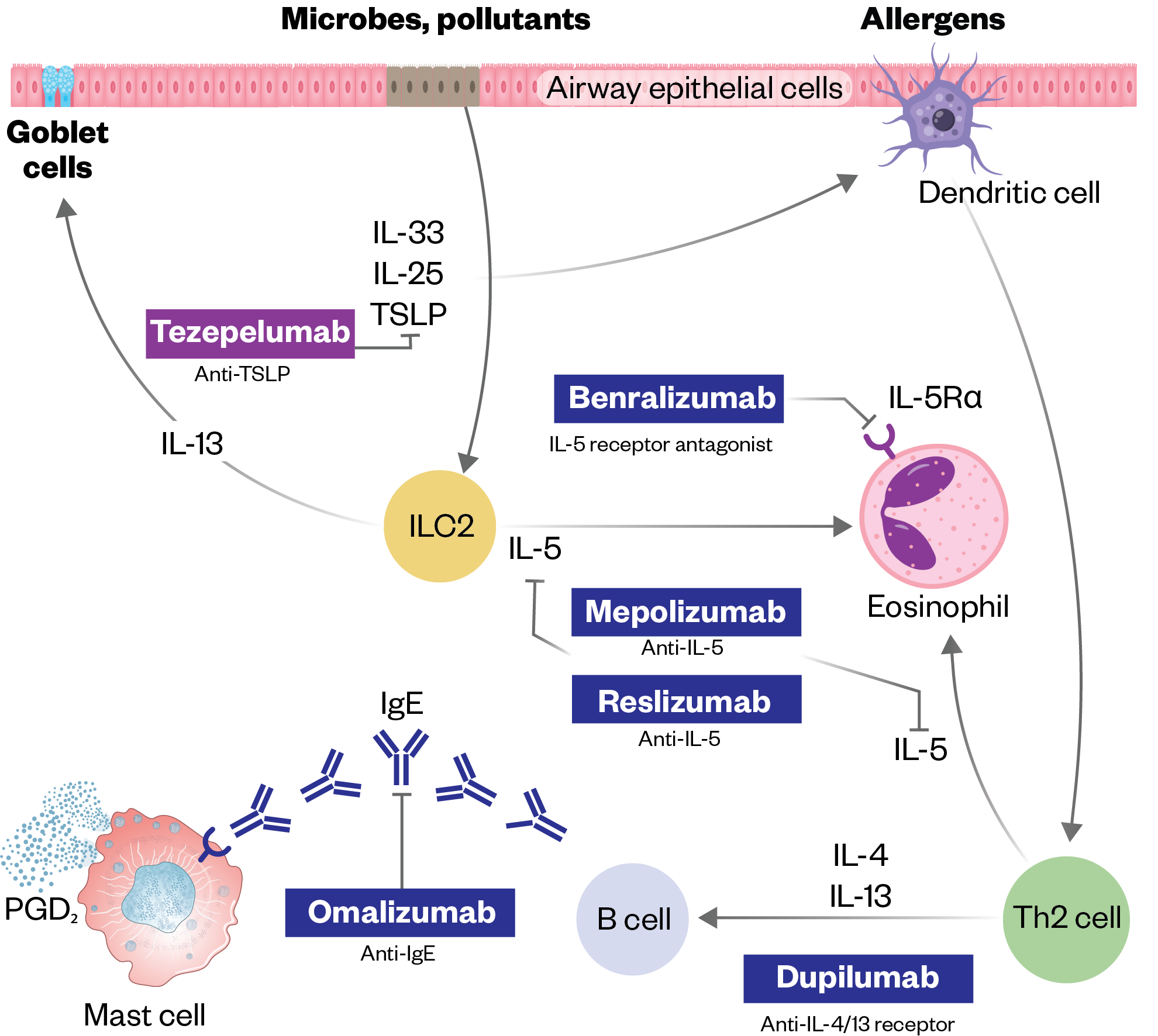

Asthma biologics have transformed the lives of people with type 2 (T2) inflammation-driven severe asthma[35]. As our understanding of the inflammatory pathway underpinning severe asthma has grown, pharmaceutical companies have developed several targeted biologics that act in different parts of the T2 inflammatory cascade (see Figure 3)[36].

Table 3 summarises their mechanism of action, administration and other important differences among asthma biologic therapies. Most are administered as a subcutaneous injection and patients can usually be taught to self-administer and receive the treatment at home. Additional considerations for initiating a biologic can be found in ‘Initiating biologics and biosimilars in practice: approach and consultation guidance’.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

To guide therapy during pregnancy, The Xolair Pregnancy Registry (EXPECT) was established as a prospective observational study to evaluate the perinatal outcomes in 250 women living in the United States who were exposed to omalizumab during pregnancy[37]. The results showed no evidence of increased risk of major congenital anomalies following exposure to omalizumab among pregnant women compared with a disease-matched cohort of pregnant women with moderate-to-severe asthma[37]. While there are limited data on pregnancy and breastfeeding in humans for other asthma biologics, individual drug licences reassure that animal studies do not suggest reproductive toxicity. Extrapolation or comparison to other biologic therapies in pregnancy should be avoided; instead, it should be considered that an acute severe asthma attack can be catastrophic for mother and baby, so the decision of whether to continue a biologic in pregnancy needs to involve shared decision making between the pregnant person and the asthma team caring for her.

Adult severe asthma networks in England

NHS England currently commissions adult severe asthma services in England and it has stipulated that the decision to initiate biologic treatment must be made by, or in collaboration with, a severe asthma multidisciplinary team (MDT) within a severe asthma specialist service[38]. These centres and networks are shown in Box 1[38].

Box 1: Severe asthma specialist centres and networks

- Birmingham Regional Severe Asthma Service (Birmingham City Hospital; Gloucester Royal Hospital; Birmingham Heartlands Hospital; Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham; Royal Derby Hospital; Russells Hall Hospital; Sandwell General Hospital; New Cross Hospital Wolverhampton; Worcestershire Royal Hospital; Royal Stoke University Hospital; University Hospital Coventry; Hereford County Hospital);

- East Midlands (Glenfield Hospital; Nottingham City Hospital);

- East of England (Addenbrookes Hospital);

- Newcastle (Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust);

- North West (Countess of Chester Hospital; Lancashire Teaching Hospital; Royal Liverpool University Hospital; Royal Preston Hospital; University Hospital of South Manchester; Wirral University Teaching Hospital; Salford Royal);

- North Central and East London (St Bartholomew’s Hospital; Royal Free Hospital; Homerton University Hospital);

- Royal Brompton and Harefield (Royal Brompton Hospital; St George’s Hospital);

- South Thames and Kent (Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust);

- South West (Somerset NHS Foundation Trust; Plymouth Hospitals; North Bristol NHS Trust; Royal Devon and Exeter; Bristol Royal Infirmary);

- Wessex (University Hospitals Southampton; Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust);

- Yorkshire (Hull Royal Infirmary; Sheffield Teaching Hospital; Northern General Hospital; Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust; Chesterfield Royal Hospital; Bridlington Hospital; Mid Yorkshire Teaching NHS Trust);

- Oxford (Oxford University Hospitals).

Based on NICE recommendations, NHS England has defined patient eligibility criteria that must be fulfilled for that person to receive NHS-funded biologic treatment. These criteria are listed in Blueteq, a web-based system for the approval and management of high-cost drugs, which must be met to access the drug[39]. The biomarker and prednisolone exposure thresholds differ among the available therapies and are listed in Table 4. These criteria may decide which biologic a person receives or render them ineligible.

Several other eligibility criteria exist that are common to all therapies; for example, biologic treatment must only be commenced in combination with optimised standard therapy (defined as a full trial of and, if tolerated, documented adherence with inhaled high-dose corticosteroids [plus another controller] and smoking cessation if clinically appropriate)[39]. Adherence must be confirmed by one or more of the following methods:

- Prednisolone and cortisol levels;

- Prescription refill checks;

- FeNO suppression test using directly observed inhaled corticosteroids[39].

The newer biologics (dupilumab and tezepelumab) also include smart inhaler monitoring as an option and tezepelumab criteria specifies level of prescription refill needed (>75%)[24,25]. Adherence is an essential criterion to be eligible to initiate an asthma biologic and continued ICS use may be necessary for optimal response on the biologic[13,40].

Medicines adherence

It is well established that poor medication adherence is a problem among patients with chronic diseases[41]. This appears to be even more pronounced in patients with asthma because they may not see their condition as chronic, but instead episodic[42]. Non-adherence to medicines in asthma is common, with adherence to inhaled therapies in airway disease consistently reported as around 50%[43]. Non-adherence is multifaceted and includes someone not being prescribed or collecting their ICS, it being used less frequently than prescribed or that their inhaler technique is poor. Pharmacists can detect non-adherence and deliver interventions to improve medicines use. Non-adherence is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, inappropriate treatment escalation, overuse of rescue therapies and avoidable healthcare costs, including emergency admissions or referral to hospital[44]. Additional information on interventions relating to adherence can be found in: ‘Children and young people with asthma: symptoms, diagnosis and the role of pharmacy‘.

Adherence quantification is fundamental in determining if a lack of asthma control is caused by under treatment or adequate treatment not being taken as intended. Adherence can be difficult to quantify and currently there is no gold standard method for its assessment. Nevertheless, there are several tools that can be used to identify and monitor poor adherence[45,46]. Table 5 compares the different types of adherence assessments and the benefits and limitations of each[45–48]. It is important to recognise and understand the different types of non-adherence to enable a tailored approach to address the issues.

High-dose oral corticosteroid prescribing

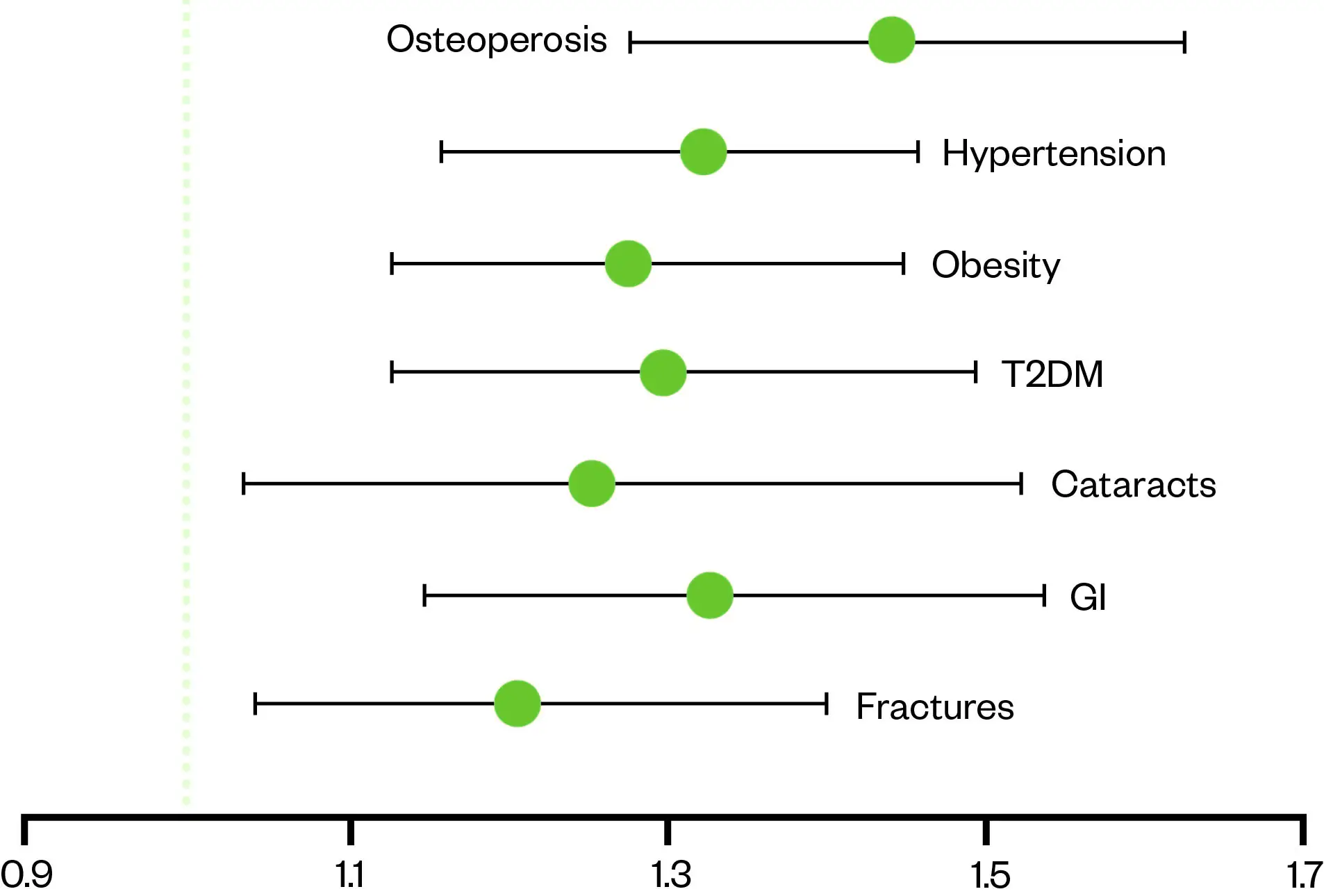

The risks of OCS, as mentioned previously, are well documented; however, there is a perception that short courses used intermittently do not pose a long-term risk[16,17]. Evidence suggests that this perception of relative safety is misplaced and adverse effects are not only dose-related but can occur in as few as four short courses (see Figure 4[16,17]).

The Pharmaceutical Journal

People with asthma who take ≥4 OCS prescriptions within one year have 1.29 times the odds of experiencing a new adverse effect within the year.

The programme team worked with the NHS Business Services Authority to develop a prednisolone volume metric that was added to the established respiratory dashboard in December 2021[30]. The new metric quantified the number of patients in England presumed to have an airways disease and prescribed prednisolone tablets in the preceding 12 months. It calculated and presented the total cumulative prednisolone dose to help clinicians identify and prioritise patients most at risk (with the highest steroid exposure) and therefore in need of a clinical review[30]. In January 2021, 33,667 patients in England were prescribed over 3,000mg of prednisolone in the preceding 12-month period (for context, 3g of prednisolone could be over ten courses of prednisolone at 40mg daily for seven days, or equivalent to a maintenance daily dose of over 8mg/day for the year). At the end of the programme, there were 3,195 fewer respiratory patients who had reached that 3g of oral prednisolone threshold[30].

The role of the pharmacist in asthma care

National guidance and specifications have partially influenced the activity that is currently being undertaken by pharmacists in respiratory care[49]. The ‘NHS long-term plan’ recommended that primary care network pharmacists are embedded in MDTs to deliver structured medication reviews, the focus being to optimise treatment; for example, through education on inhaler technique[50]. Community pharmacy contracts have offered pharmacists new opportunities to be involved in respiratory care[51,52]. In secondary care, the ‘NHS discharge medicines service‘ enables hospital pharmacy teams to refer patients to their designated community pharmacy for specific interventions or medicines support and other onward care[53]. While in tertiary severe asthma centres, the national service specification for specialised respiratory services recommends that the MDT includes a pharmacist[38].

In October 2020, Oxford AHSN surveyed pharmacists on their current respiratory activity and how the profession could contribute further[31]. The survey was circulated via various networks and responses were received from 29 pharmacists working for various organisations, including: tertiary centres; acute trusts; clinical commissioning groups; primary care networks; GP practices; academic health science networks and the Primary Care Respiratory Society[31]. Questions from the survey can be found in Box 2.

Box 2: Questions included

- Do pharmacists in your organisation identify, or support identification of patients with severe asthma that may be eligible for biologic treatment?

- Do pharmacists in your organisation refer patients with severe asthma for initiation of asthma biologics?

- Do pharmacists in your organisation initiate asthma biologics?

- Do pharmacists in your organisation prescribe asthma biologics?

- Do pharmacists in your organisation support with monitoring of patients on asthma biologics?

- Are pharmacists in your organisation involved in counselling patients prescribed asthma biologics?

- Are pharmacists in your organisation involved in training healthcare professionals on severe asthma or asthma biologics?

- Are there any other areas where you think pharmacists can be involved in the severe asthma pathway?

If the answer to the above questions was ‘yes’, respondents were asked how the service works or, if the answer was ‘no’, if there was potential to carry out activity in these areas[31].

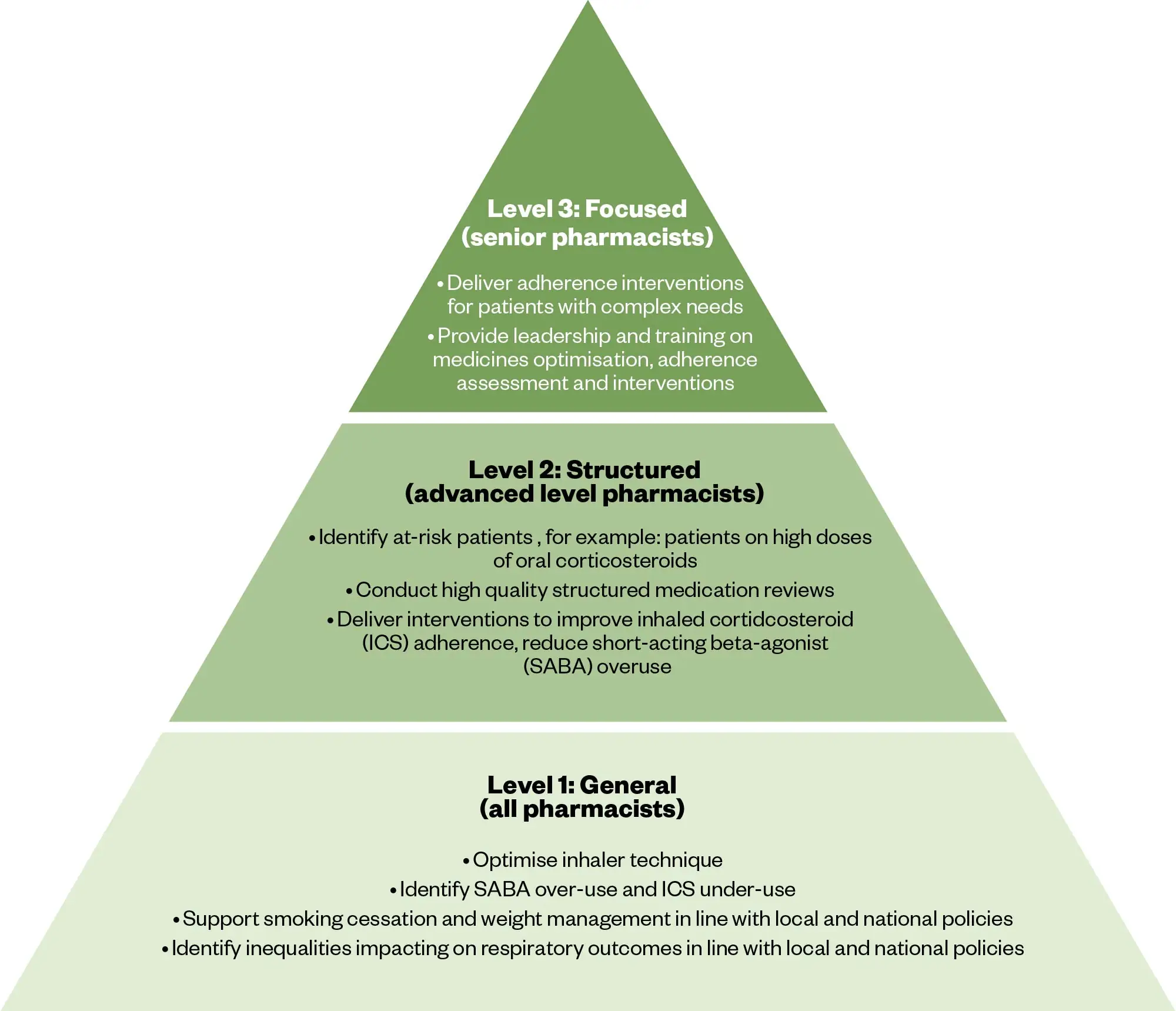

The survey results showed that most of the current pharmacist activity related to severe asthma was taking place in either secondary or tertiary care. Activity was reported in a range of areas in the pathway; however, the areas where pharmacists are currently the most active are monitoring and training[31]. Respondents expressed that the area where the greatest improvement could be made was the identification of patients (see Figure 5[31]).

When asked for specific ideas, respondents felt the following areas could be further developed.

1. Pharmacists supporting identification of patients in primary care

This could be achieved by developing practice searches to identify patients fulfilling pre-agreed criteria; practice pharmacists assessing adherence and inhaler technique and having a pathway for direct referral to the local asthma multidisciplinary team. Pharmacists working in primary care could be supported by specialist respiratory pharmacists via virtual clinics.

2. Pharmacists screening inpatients

With appropriate training and screening tools, ward-based pharmacists could identify and refer suitable patients for assessment for asthma biologic treatment.

3. Pharmacist-led clinics

Pharmacists in some centres are delivering clinics to assess and support adherence. In some cases, pharmacists prescribe biologics for hospital and subsequent home administration. Most of these clinics were in tertiary centres; however, there is potential for alternative settings (e.g., asthma hubs that feed into specialist centres).

4. Pharmacist-led training for pharmacists and healthcare professionals

Specialist pharmacists could support with training and upskilling of new or junior pharmacists and other healthcare professionals, particularly in medicines optimisation and adherence support.

5. National guidance for the role of the pharmacist in severe asthma

Pharmacists suggested national guidance and standards to support consistency in the activity of asthma pharmacists would be useful[31].

Following the survey, a pharmacy clinical subgroup consisting of pharmacists from all sectors and geographical regions was established to review the survey suggestions and, where appropriate, develop these further. The overall aim agreed upon by the group was:

‘To foster an integrated role for the pharmacist where they lead on medicines optimisation and adherence support for people with asthma.’

To ensure optimal patient outcomes, it is crucial that pharmacist roles and responsibilities are defined. The vision for this is described in Figure 6[31].

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Future perspectives and conclusion

Asthma is a common long-term condition but, unfortunately, the outcomes of patients with asthma in the UK are among the worst in Europe[54]. Significant advances have been made in the understanding of asthma pathophysiology that have in turn resulted in targeted drug therapies and more useful diagnostic tools. There is no doubt that effective implementation of these innovations will improve clinical outcomes for patients, but the large number of patients, lack of robust identification or referral of these high-risk individuals and a paucity of appropriately trained staff to manage them has meant biologic uptake in asthma has been slow.

Pharmacists can offer high-quality, individualised care in asthma and, by using the tools developed within the AAC RUP programme, they can deliver the improvements in clinical outcomes that people with asthma in the UK so desperately need.

Key points

- Engagement: When surveyed, pharmacists from all sectors expressed an interest and willingness to contribute more to the management of people with asthma;

- Support: Tools exist that assist with both the identification of people with poorly controlled asthma and their clinical review. These include: a free to download search tool (SPECTRA) that also supports patient referral; a structured asthma medication review template to guide pharmacists through the consultation and medicines optimisation; and an online self-directed learning module, which is currently being adapted by the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education and is due for release in April 2024;

- Outcomes: Initiation of asthma biologic treatment in appropriate patients is transformative. These therapies have been shown to improve symptoms, lung function, quality of life and, importantly, reduce oral corticosteroid exposure.

Financial disclosure/conflict of interest statement

HS was funded by Chiesi for attendance at the British Thoracic Society Conference.

GdA has received monies for consultancy work or sponsorship to attend conferences from: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK and Sanofi.

HR has received advisory board and speaker fees from GSK, Chiesi, AstraZeneca, Sanofi and Boehringer Ingelheim; conference support from AZ and grant funding to her institution from AZ and GSK.

JR has received advisory board and speaker fees from AZ.

Funding received from NHS England and Pharmaceutical Industry to develop resources.

Author contributions

SG and GdA led on the pharmacy workstream and developed, conducted, and analysed the survey. JR was the lead for the AAC programme and supported delivery of a number of the work packages. JR was also created a number of figures for this article. GdA developed the medication adherence educational module. SG, HS, and GdA drafted the first manuscript. All authors read and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Marianna Lepetyukh. Project Manager Oxford Academic Health Science Network.

- 12023 GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Global Initiative for Asthma. 2023. https://ginasthma.org/2023-gina-main-report/ (accessed April 2024)

- 2Holmes S, Kane B, Pugh A, et al. Poorly controlled and severe asthma: triggers for referral for adult or paediatric specialist care – a PCRS pragmatic guide. Prim Care Respir Șoc. 2019;1:22–7.

- 3Holguin F, Cardet JC, Chung KF, et al. Management of severe asthma: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2019;55:1900588. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00588-2019

- 4SIGN 158 British guideline on the management of asthma. The British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). 2019. https://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-158-british-guideline-on-the-management-of-asthma (accessed April 2024)

- 5Asthma: What is the prevalence of asthma? Clinical Knowledge Summary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/asthma/background-information/prevalence/ (accessed April 2024)

- 6Slipping through the net: The reality facing patients with difficult and severe asthma. Asthma UK. 2018. https://www.asthmaandlung.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-03/auk-severe-asthma-gh-final.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 7Kerkhof M, Tran TN, Soriano JB, et al. Healthcare resource use and costs of severe, uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma in the UK general population. Thorax. 2017;73:116–24. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210531

- 8Porsbjerg C, Melén E, Lehtimäki L, et al. Asthma. The Lancet. 2023;401:858–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)02125-0

- 9Cumella A. Living in limbo: the scale of unmet need in difficult and severe asthma. Asthma + Lung UK. 2019. https://www.asthmaandlung.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-03/living-in-limbo—the-scale-of-unmet-need-in-difficult-and-severe-asthma.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 10Majellano EC, Clark VL, Winter NA, et al. <p>Approaches to the assessment of severe asthma: barriers and strategies</p> JAA. 2019;Volume 12:235–51. https://doi.org/10.2147/jaa.s178927

- 11Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80 (accessed April 2024)

- 12Why Asthma Still Kills: the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) Confidential Enquiry Report. Royal College of Physicians. 2014. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/why-asthma-still-kills-full-report.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 13Kim LHY, Saleh C, Whalen-Browne A, et al. Triple vs Dual Inhaler Therapy and Asthma Outcomes in Moderate to Severe Asthma. JAMA. 2021;325:2466. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.7872

- 14Paggiaro P, Bacci E. Montelukast in asthma: a review of its efficacy and place in therapy. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 2010;2:47–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622310383343

- 15Jackson DJ, Busby J, Pfeffer PE, et al. Characterisation of patients with severe asthma in the UK Severe Asthma Registry in the biologic era. Thorax. 2020;76:220–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215168

- 16Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH, Globe G, et al. Oral corticosteroid exposure and adverse effects in asthmatic patients. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2018;141:110-116.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.009

- 17Price D, Castro M, Bourdin A, et al. Short-course systemic corticosteroids in asthma: striking the balance between efficacy and safety. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29:190151. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0151-2019

- 18Asthma Biologics Adoption Barriers and Suggested Solutions. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. https://www.healthinnovationoxford.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Asthma-Biologics-Adoption-Report-final.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 19The HASTE tool. Oxford Academic Health Science Network . 2022. https://www.healthinnovationoxford.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/AB-podcast-poster.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 20Xolair 150 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4725/smpc#gref (accessed April 2024)

- 21Nucala 100 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10563/smpc (accessed April 2024)

- 22Cinqaero (reslizumab) 10 mg/mL concentrate for solution for infusion. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2023. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4370 (accessed April 2024)

- 23Fasenra 30 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2023. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4370 (accessed April 2024)

- 24Dupixent 200 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11323/smpc (accessed April 2024)

- 25Tezspire 210 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2023. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/14064 (accessed April 2024)

- 26Asthma Biologics Toolkit. Oxford Academic Health Science Network. https://www.healthinnovationoxford.org/our-work/respiratory/asthma-biologics-toolkit/asthma-biologics-overview/ (accessed April 2024)

- 27Rapid Uptake Products Asthma Biologics AAC Consensus Pathway: Management of Uncontrolled Asthma in Adults. Oxford Academic Health Science Network. 2022. https://www.healthinnovationoxford.org/our-work/respiratory/asthma-biologics-toolkit/aac-consensus-pathway-for-management-of-uncontrolled-asthma-in-adults/ (accessed April 2024)

- 28Rapid uptake products. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/aac/what-we-do/innovation-for-healthcare-inequalities-programme/rapid-uptake-products/ (accessed April 2024)

- 29NHS Accelerated Access Collaborative. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/aac/ (accessed April 2024)

- 30Transforming asthma care through improved access to diagnostics and innovative treatments. Oxford Academic Health Science Network. https://www.healthinnovationoxford.org/our-work/respiratory/asthma-biologics-toolkit/ (accessed April 2024)

- 31Understanding opportunities to improve Severe Asthma Care in England. Oxford Academic Health Science Network. 2022. https://www.healthinnovationoxford.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Severe-Asthma-Benchmarking-Summary-of-Findings-1.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 32Ryan D, Heatley H, Heaney LG, et al. Potential Severe Asthma Hidden in UK Primary Care. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2021;9:1612-1623.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.053

- 33SPECTRA. SPECTRA. 2024. https://suspected-severe-asthma.co.uk/ (accessed April 2024)

- 34Asthma structured medication review template. Oxford Academic Health Science Network. https://www.healthinnovationoxford.org/our-work/respiratory/asthma-biologics-toolkit/clinical-resources/asthma-structured-medication-review-template/ (accessed April 2024)

- 35Hearn AP, Kent BD, Jackson DJ. Biologic treatment options for severe asthma. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2020;66:151–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2020.10.004

- 36Pelaia C, Crimi C, Vatrella A, et al. Molecular Targets for Biological Therapies of Severe Asthma. Front. Immunol. 2020;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.603312

- 37Namazy JA, Blais L, Andrews EB, et al. The Xolair Pregnancy Registry (EXPECT): Perinatal outcomes among pregnant women with asthma treated with omalizumab (Xolair) compared against those of a cohort of pregnant women with moderate-to-severe asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2019;143:AB103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2018.12.312

- 38Specialised Respiratory Services (adult) – Severe Asthma. NHS England. 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/spec-services/npc-crg/group-a/a01/ (accessed April 2024)

- 39Blueteq. Blueteq. https://www.blueteq-secure.co.uk/Trust/default.aspx (accessed April 2024)

- 40d’Ancona G, Kavanagh JE, Dhariwal J, et al. Adherence to inhaled corticosteroids and clinical outcomes following a year of benralizumab therapy for severe eosinophilic asthma. Allergy. 2021;76:2238–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14737

- 41d’Ancona G, Weinman J. Improving adherence in chronic airways disease: are we doing it wrongly? Breathe. 2021;17:210022. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0022-2021

- 42Amin S, Soliman M, McIvor A, et al. <p>Understanding Patient Perspectives on Medication Adherence in Asthma: A Targeted Review of Qualitative Studies</p> PPA. 2020;Volume 14:541–51. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.s234651

- 43Holmes J, Heaney LG. Measuring adherence to therapy in airways disease. Breathe. 2021;17:210037. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0037-2021

- 44Lee J, Tay TR, Radhakrishna N, et al. Nonadherence in the era of severe asthma biologics and thermoplasty. Eur Respir J. 2018;51:1701836. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01836-2017

- 45Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to Medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–97. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra050100

- 46Holmes J, Heaney L. Measuring adherence to therapy in airways disease. Breathe (Sheff). 2021;17:210037.

- 47Quirke-McFarlane S, Weinman J, d’Ancona G. A Systematic Review of Patient-Reported Adherence Measures in Asthma: Which Questionnaire Is Most Useful in Clinical Practice? The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2023;11:2493–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2023.03.034

- 48McNicholl DM, Stevenson M, McGarvey LP, et al. The Utility of Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide Suppression in the Identification of Nonadherence in Difficult Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1102–8. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201204-0587oc

- 49Clements J, Bowman E, Tolhurst R, et al. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the respiratory or sleep multidisciplinary team. Breathe. 2023;19:230123. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0123-2023

- 50The NHS Long Term Plan. NHS. 2019. www.longtermplan.nhs.uk (accessed April 2024)

- 51Pharmacy Quality Scheme Guidance 2021/22. NHS England. 2022. https://www.cpsc.org.uk/application/files/8116/3109/5775/NHSEI_Pharmacy-Quality-Scheme-guidance-September-2021-22-Final.pdf (accessed April 2024)

- 52NHS New Medicine Service. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/pharmacy-services/nhs-new-medicine-service/ (accessed April 2024)

- 53Discharge Medicines Service. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/nhs-discharge-medicines-service/ (accessed April 2024)

- 54Action for lung health in the UK. International Respiratory Coalition. https://international-respiratory-coalition.org/countries/uk/ (accessed April 2024)