Abstract: Health inequalities are unfair, avoidable differences in health and access to healthcare between population groups. This article explains the link between social factors and health, the wider context of health inequalities in the UK, as well as exploring the role that community pharmacy can play in addressing health inequalities, with examples of work that is already underway.

Key words: health inequalities; equality; life expectancy; social determinants of health; community pharmacy

Introduction

Health inequalities are defined as “unfair and avoidable differences” in health and access to healthcare across communities and geographical areas, or specific population groups (e.g. sex workers, vulnerable migrants and people without homes)[1,2].

People may experience health inequalities in a wide range of areas, including:

- Access to care (e.g. the availability of a specific health service or healthcare personnel);

- Experience and quality of care (e.g. being treated with dignity);

- Wider determinants of health (e.g. access to green spaces, good education, income);

- Life expectancy (e.g. differences in life expectancy for people in different geographical areas).

In his 2010 report, Sir Michael Marmot highlighted that reducing health inequalities “is a matter of fairness and social justice” because they are avoidable and do not occur by chance[2]. These are systemic differences that are largely beyond an individual’s control.

In the decade following Marmot’s report, life expectancy across the UK has stagnated (see Figure). Marmot’s 2020 review — ’10 years on’ — highlighted that life expectancy had fallen in the most deprived communities outside London for women and in some regions (the North East, Yorkshire and the Humber and the East of England) for men. These data show that health outcomes for those living in the northern parts of England were significantly worse than for those in the south of England. People living in the north of England showed an increased number of years in ill health, compared with those living in the south of England, and this is more prominent in those who live in poorer areas[3].

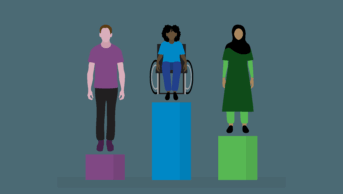

Health inequalities do not just affect people from an ethnic minority background or those on low incomes; they are underpinned by a combination and interplay of social and economic conditions, which is known as intersectionality.

For example, education, work environment, housing, water, sanitation and individual lifestyle factors — such as smoking, being physically active and employment — all affect a person’s health outcomes. These are called the ‘social determinants of health’. The Marmot Review states that action on health inequalities requires action across all the social determinants of health[2,4]. As a result, having good, secure employment with a living wage and support for healthy living initiatives, such as access to outdoor spaces, clean air and acceptable living standards, could all reduce health inequalities.

Importance of addressing health inequalities

The impact of health inequalities is profound and permeates all aspects of society. Inequalities are a matter of life and death, health and sickness, or wellbeing and misery[2]. Populations in poorer areas tend to experience lower wages and job instability, but they also have higher stress levels, more mental health challenges and poorer physical health[2]. This demographic is more likely to live with multiple chronic illnesses and mental health disorders and may have overall shorter lives[2,5]. In 2020–2021, the life expectancy gap between the most and least deprived quintiles of England was 8.6 years[6]. The figure below shows UK life expectancy at birth for males and females between 1980–1982 and 2020–2022[7]. The male–female difference in life expectancy is greater in more deprived areas[6].

These issues present challenges to individuals in maintaining stable employment and achieving good educational outcomes, resulting in increased demand placed on healthcare systems. Therefore, everyone in society is affected by health inequalities because everyone is affected by these factors. It is imperative, therefore, to put efforts into reducing inequalities[2,8]. Less time in ill health means more economic productivity, less pressure on health systems owing to chronic ill health, and improved social lives.

Addressing health inequalities is also important because it is a matter of social justice and fairness. Moreover, the NHS urges healthcare professionals to embody NHS values by ensuring that high-quality healthcare is available and accessible to all (see Box)[9].

Box: The NHS’s values

- Working together for patients: patients come first in everything we do;

- Respect and dignity: we value every person — whether patient, family member, carer, or staff — as an individual, respect their aspirations and commitments in life, and seek to understand their priorities, needs, abilities and limits;

- Commitment to quality of care: we earn the trust placed in us by insisting on quality and striving to get the basics of quality of care — safety, effectiveness and patient experience — right every time;

- Compassion: we ensure that compassion is central to the care we provide and respond with humanity and kindness to each person’s pain, distress, anxiety or need;

- Improving lives: we strive to improve health and wellbeing and people’s experiences of the NHS;

- Everyone counts: we maximise our resources for the benefit of the whole community, and make sure nobody is excluded, discriminated against or left behind.

In 2013, the UCL Institute of Health Equity published a report on the role of healthcare professionals in reducing health inequalities, including workforce training, practical actions to be taken during interactions with patients, ways of working in partnership and the role of advocacy[10]. Although there was no representation of pharmacy in that report, pharmacy has always been a core stakeholder in healthcare provision and access, with evolving roles in clinical provision and patient care.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted many existing health disparities between population groups. People who were already disadvantaged suffered worse health outcomes and higher mortality[11].

Healthcare workers, including pharmacists, stepped up during the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery[12,13]. As an integral component of local communities, pharmacies remained open to the public when other healthcare providers had restricted their access. Pharmacists consistently provided ongoing support to patients and played a major role in administering flu and COVID-19 vaccinations[13]. The impact that healthcare providers, including pharmacists, had on public health and efforts to reduce inequalities in health have been published across the four nations of the UK[14,15].

Addressing health inequalities is complex and challenging. It requires policy change, government funding for the right interventions, and integrated working between local authority, health services, voluntary sectors and grassroot communities. These are not easy issues, especially in the current economic climate following a period of high inflation, higher interest rates, stretched budgets and overall economic uncertainty. When considered alongside the increasing cost of medicines and overall cost of running a pharmacy amid high patient demand, the challenges are considerable[16,17].

Community pharmacies across the UK play a crucial role in enabling fair access to healthcare because pharmacies are predominantly situated in the heart of local communities. This positioning enables community pharmacy teams to build trust and respect, foster good relationships, gather information about local needs and priorities, and provide information to benefit patients and members of the public.

Core20Plus5 framework

NHS England has developed the CORE20Plus5 framework for tackling health inequalities experienced by adults[18]. It has also been adapted to apply to children and young people at a national and system level. The approach focuses on the most deprived 20% of the national population, plus five primary clinical areas for accelerated improvement:

- Maternity;

- Severe mental illness;

- Chronic respiratory disease;

- Early cancer diagnosis;

- Hypertension case finding.

It also acknowledges that smoking cessation positively affects all five clinical areas.

Community pharmacies should use the Core20plus5 framework to establish closer working relationships and collaborations within integrated care systems (ICSs) to identify their ‘Plus’ populations. The ‘Plus’ represents population groups who experience poorer than average health access, who may not be captured in the Core20 alone and would benefit from a tailored healthcare approach.

For example, community pharmacies, in collaboration with their ICSs, could provide pharmaceutical services or enhanced services that are locally negotiated with the local pharmaceutical committees and local authorities. Such services may be tailored to the needs of the population, with a view to achieving equitable outcomes for the most disadvantaged, deprived or excluded groups. Examples of local enhanced services may include translation services for medication and health advice, learning disabilities medication review, smoking cessation and substance misuse.

Importance of integrated working

ICSs were established across England in 2022. The aim is for these partnerships to plan and work together with a focus on delivering joined-up health and care services. They are aimed at improving population health and reducing inequalities in outcomes, experience and access to healthcare[19]. Community pharmacy teams within these ICSs play a significant role in disease prevention, monitoring, and providing advice and health coaching to their local communities.

Within weeks of the inception of ICSs, a new vision for integrating primary care was set out in the ‘Fuller stocktake report’[20]. The report called for more proactive, personalised care with support from a multidisciplinary team of professionals, also known as ‘integrated neighbourhood teams’, which will evolve from primary care networks (PCNs). According to the report, the PCNs that were most effective in improving population health and tackling health inequalities were those that worked in partnership with their communities and local authority colleagues[20]. These structural changes have made it increasingly necessary for community pharmacy teams to work collaboratively with local partners to improve the health and wellbeing of their patients, achieve population health goals and reduce inequalities.

Pharmacists are increasingly working in an integrated way as part of the multidisciplinary healthcare team. Community pharmacists who work closely with general practice teams have reported better working relationships, which result in improved patient outcomes[21]. The contribution of community pharmacists across the UK and globally to public health and the reduction of health inequalities has been previously reported[15,22].

Strategic directions for community pharmacy have been set in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and England[4,23–27]. These strategic plans encourage pharmacy professionals to engage patients in shared decision-making, have person-centred conversations, improve access to care and help prevent ill-health through health improvement services, such as immunisations, smoking cessation, hypertension case finding and weight management. They can be used as a base to guide pharmacy teams on practical ways to address health inequalities through community pharmacies[8,21,23–28]. However, to successfully reduce health inequalities, community pharmacy teams must work collaboratively with other teams across geographical areas and neighbourhoods[20].

Across the four nations of the UK, there are many examples of the contributions that community pharmacies have made to addressing health inequalities and ambitions to integrate into health and social care teams, a selection of which are summarised below.

Northern Ireland

Since the launch of the service in July 2022, community pharmacists across Northern Ireland provided almost 22,000 emergency hormonal contraception (EHC) by November 2023[28]. Funding was also secured to enable the roll-out of a regional Pharmacy First Service for the management of uncomplicated UTI in women aged 16–64 years from November 2023 until the end of March 2024[29]. In addition, the Pharmacy First Service was launched in Northern Ireland for winter conditions and EHC in March 2022[4]. These schemes are good examples of how community pharmacies are supporting improved access to primary care.

Wales

Mental and social wellbeing is a strategic priority in Wales and Public Health Wales has committed to working with health and social care professionals to reduce inequalities in mental and social well-being[25]. The report by the Welsh Health and Social Care Committee stated that “connection” is imperative in tackling health inequalities. By connecting people with services and their communities, positive environments that support and nurture positive mental health can be co-produced by people with lived experience and the wider health and social care workforce.

The paper suggested that community pharmacists could play a greater role in supporting people experiencing low-level mental health issues[25,26]. This can be facilitated by community pharmacy services, such as the discharge medicines service and new medicine service (NMS).

The NMS is already available in England for certain patient groups and conditions and is currently being piloted to include prescriptions for antidepressants[30]. If the pilot in England is successful, the service could potentially be implemented in Wales for people starting antidepressants while providing them with emotional and psychological support through community pharmacy teams[24,30].

Additionally, in a response to the Health and Social Care Committee, Community Pharmacy Wales outlined an aspiration to tackle health inequalities through smoking cessation and weight management services that would enable pharmacies to engage in the National Exercise Referral Scheme[24].

Scotland

In Scotland, community pharmacies have been most effective in reducing health inequalities by developing and negotiating free national pharmacy services for all community patients. These services include NHS Pharmacy First and NHS Pharmacy First Plus, which improve access to healthcare advice and the treatment of common conditions, including medicines that would previously require a GP prescription[31].

Personal characteristics can predispose groups of people to being treated differently, which can exacerbate health inequalities[32]. For example, women who are unable to access timely contraception may suffer unintended consequences, such as unwanted pregnancies, which could adversely affect maternal and child health[33]. In 2021, to address this inequality, community pharmacies in Scotland began offering a walk-in service for long-term contraceptive supply to women who struggled to gain timely access to sexual health services or their GP. This resulted in participants reporting greater awareness of contraception and contraceptive services[14].

Drug-related deaths have increased significantly in Scotland and Community Pharmacy Scotland has prioritised this as an area for tackling health inequalities[31]. Currently, almost all community pharmacy teams in Scotland deliver support for people who use drugs and those in treatment for drug use, on behalf of the NHS; however, there is unwanted variation in the level of service provision and further support is required from the health boards to enable community pharmacy teams to provide a package of care that addresses population health needs and reduces inequalities in healthcare provision[31].

England

In May 2023, the government announced its delivery plan for recovering access to primary care and its commitment to expanding community pharmacy services through a Pharmacy First model and expansion of the blood pressure and contraception services[34]. Pharmacy First was launched on 31 January 2024 and enables community pharmacies to supply prescription-only medicines for seven common conditions. This, in addition to the expansion of the oral contraception and blood pressure check services, will provide pharmacy teams with the opportunity to prevent ill health, and engage with and improve healthcare access for those who otherwise find it challenging to access healthcare. To support pharmacists with this expanded services list, NHS England has launched training packages, including clinical examination skills and independent prescribing, to equip community pharmacists with the skills to deliver these and future clinical services effectively[35].

Improving cooperation

Community pharmacists have called attention to how a lack of interoperability between pharmacy and GP systems acts as a barrier to providing optimal patient care[36]. However, there are innovations in community pharmacy (e.g. independent prescribing) and the potential for instant digital communication between community pharmacy and other healthcare providers (e.g. patient records). This could be a game-changer because more people are likely to access services within the community pharmacy if systems are better connected[27]. NHS England is funding improvements to the digital infrastructure between general practice and community pharmacy and, since February 2024, community pharmacy IT systems have been automatically sending details of a community pharmacy consultation to the GP clinical IT system, ready for a GP to check and update the patient’s record. This will remove the need for general practice staff to transcribe information from emails.

Interventions beyond the provision of clinical services

Community pharmacy teams can go beyond the provision of clinical services to improve public awareness of health priorities. They can build on the trust and rapport they have developed locally to participate in community outreach efforts and pursue closer working partnerships with other stakeholders, such as the local authority, PCNs, health and wellbeing workers, and the voluntary, charity and faith networks.

Often, community pharmacy staff reflect the the diversity of the populations they serve. Staff who have knowledge of the local area and population can help to facilitate engagement in public health campaigns that address the social determinants of health. This may include signposting people to link workers and social prescribers within a given geographic area or integrated neighbourhood team.

Community pharmacy teams can encourage physical activity, for example, by signposting people to green spaces or leisure or fitness centres. These interventions could support healthy-living discussions during consultations for a range of physical and mental health-related conversations. Other interventions include motivational interviewing, practical weight-management support, or culturally competent advice for healthy eating suited to the local population’s needs.

Behavioural insight is useful for helping community pharmacy teams understand local populations. It concerns how people perceive things, make decisions and behave. Community pharmacy teams alongside local stakeholders can use behavioural insights to create solutions and services that are tailored to local priorities[37]. Co-creation or co-designing means designing services with the people for whom the service or intervention is meant for. Through outreach, co-design and creation of services, community pharmacy teams will be more likely to successfully engage with communities and people from varying backgrounds to improve health outcomes.

Inclusive pharmacy practice and culturally competent healthcare

The ‘Joint national plan for inclusive pharmacy practice in England’ was published in 2021[38]. The plan outlines two patient-facing aims for pharmacy professionals:

- To work collaboratively to develop and embed inclusive pharmacy professional practice into everyday care for patients and members of the public;

- To support the prevention of ill-health and address health inequalities within diverse communities.

An inclusive pharmacy resource was subsequently developed to help pharmacy teams deliver culturally competent healthcare for communities and people with an ethnic minority background[39].

Cultural competence is about being aware of one’s own cultural beliefs and values, and acknowledging that these may be different from other people’s cultural values. Developing cultural competence builds self-awareness and facilitates effective and engaging communication with others. Practical ways to practice inclusive pharmacy include making provisions for alternative languages (e.g. translating labels or instructions) and providing different formats of healthcare advice, such as telephone translation services, to suit local populations.

Stress on pharmacy professionals

Two reports by Public Health England confirmed that COVID-19 had a disproportionate impact on staff and communities from black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds[5,40]. As pharmacy teams work to address inequalities in health, there is a need for introspection and understanding of the health and social care needs of the pharmacy team itself. A stressful work environment negatively affects the health and wellbeing of staff and their productivity. Low morale, poor productivity and absence from work can prove expensive for employers. Furthermore, results of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society workforce wellbeing survey results pointed to the current pressure that is being faced by community pharmacy team members and the impact on wellbeing[41].

The ‘Pharmacy workforce race equality standard report’, published in September 2023, showed that pharmacy team members of black, Asian and minority ethnic origin experience more harassment, discrimination, bullying and abuse, and poorer career progression than white pharmacy team members. It also highlights that pharmacy team members of Black ethnic origin do not feel supported for career progression or promotion, and that Black, Asian and minority ethnic female pharmacy team members report the most personal discrimination at work[42].

Fairness and inclusion are essential in tackling health inequalities. Healthcare teams have the opportunity to be more innovative when they are composed of members with diverse backgrounds, and well engaged and supported diverse teams improve patient outcomes[38,43]. To retain diverse teams, support pharmacy staff by providing compassionate leadership, improving workplace conditions, sharing good practice and committing to inclusive pharmacy practice principles. According to the ‘Joint national plan for inclusive pharmacy practice in England’, “leaders valuing diversity and fairness results in support and inclusion for all patients and staff”[38].

Workforce pressures

To tackle health inequalities, community pharmacy teams must have the capability and capacity to do so effectively. The UK has been facing a shortage in the pharmacy workforce for some time. The ‘NHS Long Term Workforce Plan’ for England was announced in June 2023; it calls for change to the status quo and outlines ambitious plans to train, retain and reform the NHS workforce[44].

Community pharmacy teams should also engage with these ambitions[44]. To effectively tackle inequalities in access to healthcare through community pharmacy, the right number of staff with the right training and skill mix are needed to deliver high-quality, safe and successful patient-centred care.

Population health and data

Data and dashboards are very useful for strategic planning and population health management. Community pharmacy teams can develop expertise in data handling by working with other stakeholders within the ICS and integrated neighbourhood teams. The work of pharmacists reaching out to help their local communities have been documented[45].

The ‘NHS community pharmacy hypertension case-finding service’, launched in October 2021, is a good example. Hypertension case-finding is one of the five core clinical priority areas in the Core20plus5 framework. Data about the service are published in the ‘Strategic Health Asset Planning and Evaluation (SHAPE)’ Atlas, which can be used to target users of community pharmacies that are located within the top 20% most-deprived areas, to identify gaps in hypertension case finding or blood pressure optimisation[45]. This is one way in which community pharmacy teams in England can reduce health inequalities.

Commissioners, local councils and public health professionals can identify local community pharmacies that are registered and actively providing the ‘NHS community pharmacy blood pressure check service’, as well as the number of patients seen monthly and cumulatively since the service launched.

The data enable users to identify the prevalence of hypertension within defined populations and to understand the demographics of the population served by that pharmacy. Community pharmacy teams can work with their local pharmaceutical committee, cardiovascular disease prevention lead or community pharmacy clinical leads to understand the prevalence of hypertension in their neighbourhoods through the ‘SHAPE’ Atlas.

Fingertips, a collection of national public health profiles data, is a useful resource for pharmacy teams. It allows them to view indicators across a range of health and wellbeing categories, such as child and maternal health, musculoskeletal health and respiratory disease. Support is also available from the local knowledge and intelligence service, which can provide answers to specific questions and information about local public health intelligence across regions. Finally, the Healthcare Inequalities Improvement Dashboard provides strategic indicators relating to healthcare inequalities and covers data relating to the five clinical areas in the Core20Plus5 framework.

Data may not always be available or complete, but this should not hinder efforts to improve the health and wellbeing of local populations. In the meantime, data quality can be improved by making efforts to ensure accurate and comprehensive data entry into patients’ records, such as age, ethnicity, gender and deprivation (via postcode).

Conclusion

Health inequalities are unfair and create avoidable differences in health and access to healthcare. Community pharmacy teams can play an important role in reducing health inequalities and improving access to good quality healthcare in the community through the provision of clinical services.

However, success will require pharmacy teams to avoid silo working, go beyond clinical services provision, and fully integrate with other stakeholders in the provision of health and social care services within integrated neighbourhood teams and ICSs.

Strong professional leadership is required to improve workplace culture and the experience of the pharmacy workforce. Finally, population health data are a useful tool for identifying priority areas for intervention.

- 1Williams E, Buck D, Babalola G, et al. What are health inequalities? The King’s Fund. 2020. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/what-are-health-inequalities (accessed March 2024)

- 2Marmot M. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review. Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010. The Marmot Review. 2010. https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 3Marmot M. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ. 2020;m693. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m693

- 4Building the Community — Pharmacy Partnership Programme. Community Development and Health Network. 2019. https://www.cdhn.org/bcpp (accessed March 2024)

- 5Beyond the data: Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on BAME groups. Public Health England. 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5ee761fce90e070435f5a9dd/COVID_stakeholder_engagement_synthesis_beyond_the_data.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 6Segment Tool. Public Health England Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. 2023. https://analytics.phe.gov.uk/apps/segment-tool/ (accessed March 2024)

- 7Baker C. Health Inequalities: Income Deprivation and North/South Divides. House of Commons Library. 2019. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/health-inequalities-income-deprivation-and-north-south-divides (accessed March 2024)

- 8Fell G. Reframing Health Inequalities. Greg Fell Public Health. 2018. https://gregfellpublichealth.wordpress.com/2018/02/24/reframing-health-inequalities/comment-page-1 (accessed March 2024)

- 9NHS Constitution. NHS Health Careers. https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/working-health/working-nhs/nhs-constitution (accessed March 2024)

- 10Allen M, Allen J, Hogarth S, et al. Working for Health Equity: The Role of Health Professionals. Institute of Health Equity. 2013. https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/working-for-health-equity-the-role-of-health-professionals (accessed March 2024)

- 11Mishra V, Seyedzenouzi G, Almohtadi A, et al. Health Inequalities During COVID-19 and Their Effects on Morbidity and Mortality. JHL. 2021;Volume 13:19–26. https://doi.org/10.2147/jhl.s270175

- 12No going back: how the pandemic is changing community pharmacy. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2020.20208309

- 13Visacri MB, Figueiredo IV, Lima T de M. Role of pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2021;17:1799–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.07.003

- 14Patterson S, McDaid L, Saunders K, et al. Improving effective contraception uptake through provision of bridging contraception within community pharmacies: findings from the Bridge-it Study process evaluation. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e057348. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057348

- 15Community pharmacists’ contribution to public health: assessing the global evidence base. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2018.20204556

- 16NHS drug costs in England see biggest rise for five years to almost £18bn . Pharmaceutical Journal. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2022.1.165511

- 17‘Catastrophic implications’: the pharmacy closures widening health inequalities. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2023.1.172891

- 18National Health Inequalities Programme. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme (accessed March 2024)

- 19What are integrated care systems? NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/integratedcare/what-is-integrated-care (accessed March 2024)

- 20Fuller C. Next Steps for Integrating Primary Care: Fuller Stocktake Report. NHS England. 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/next-steps-for-integrating-primary-care-fuller-stocktake-report.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 21Osasu YM, Mitchell C, Cooper R. Use of direct oral anticoagulants in primary care: a qualitative study integrating patient and practitioner perspectives. BJGP Open. 2022;6:BJGPO.2021.0226. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpo.2021.0226

- 22Ashiru-Oredope D, Harrison T, Wright E, et al. Barriers and facilitators to pharmacy professionals’ specialist public health roles: a mixed methods UK-wide pharmaceutical public health evidence review. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2022;30:ii2–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpp/riac089.001

- 23Finch D, Wilson H, Bibby J. Leave no one behind: The state of health and health inequalities in Scotland. The Health Foundation. 2023. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/leave-no-one-behind (accessed February 2024)

- 24Community Pharmacy Wales Response to the Health and Social Care Committee’s request for written evidence: Welsh Government’s plan for transforming and modernising planned care and reducing waiting lists. Community Pharmacy Wales. 2022. https://business.senedd.wales/documents/s126402/PCWL%2001%20-%20Community%20Pharmacy%20Wales.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 25Connecting the dots: tackling mental health inequalities in Wales. Welsh Parliament Health and Social Care Committee. 2022. https://senedd.wales/media/1uchw5w1/cr-ld15568-e.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 26Working Together for a Healthier Wales. Our long-term strategy 2023-2035. Public Health Wales. 2023. https://phw.nhs.wales/about-us/board-and-executive-team/board-papers/board-meetings/2022-2023/30-march-2023/board-papers-30-march-2023/411a-board-20230330-long-term-strategy-2023-2035-detailed-document (accessed March 2024)

- 27Pharmacy 2030: a professional vision. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2022. https://www.rpharms.com/pharmacy2030 (accessed March 2024)

- 28Pharmacy First: Emergency Hormonal Contraception. Business Services Organisation. 2023. https://bso.hscni.net/directorates/operations/family-practitioner-services/pharmacy/contractor-information/contractor-communications/hscb-services-and-guidance/pharmacy-first-service/pharmacy-first-emergency-hormonal-contraception/ (accessed March 2024)

- 29Pharmacy First: Service – Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) in Women Aged 16–64 years. Business Services Organisation. 2023. https://bso.hscni.net/directorates/operations/family-practitioner-services/pharmacy/contractor-information/contractor-communications/hscb-services-and-guidance/pharmacy-first-service/pharmacy-first-pilot-service-uncomplicated-urinary-tract-infections-uti-in-women-aged-16-64-years/ (accessed March 2024)

- 30NHS New Medicine Service. NHS England. 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/nhs-new-medicine-service (accessed March 2024)

- 31Inquiry into Health Inequalities Response. Community Pharmacy Scotland. 2024. https://www.cps.scot/consultations/inquiry-into-health-inequalities (accessed March 2024)

- 32Protected characteristics. Equality and Human Rights Commission. 2021. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/equality/equality-act-2010/protected-characteristics (accessed March 2024)

- 33Wellings K, Jones KG, Mercer CH, et al. The prevalence of unplanned pregnancy and associated factors in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). The Lancet. 2013;382:1807–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62071-1

- 34Pharmacy First Letter to Contractors. Department of Health and Social Care. 2023. www.gov.uk/government/publications/pharmacy-first-contractual-framework-2023-to-2025/pharmacy-first-letter-to-contractors (accessed March 2024)

- 35New Clinical Examination Skills Training for Community Pharmacists Launched. Health Education England. 2023. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/news-blogs-events/news/new-clinical-examination-skills-training-community-pharmacists-launched (accessed March 2024)

- 36Osasu YM. Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of Direct Oral Anticoagulant Medicines Optimisation Primary Care: a Qualitative Study. PhD thesis – University of Sheffield. 2021. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/29449/ (accessed March 2024)

- 37Behavioural Insights and Public Policy: Lessons from Around the World. OECD. 2017. https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/behavioural-insights-and-public-policy-9789264270480-en.htm (accessed March 2024)

- 38Joint National Plan for Inclusive Pharmacy Practice. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2021. https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Inclusive%20Pharmacy%202021/Joint%20National%20Plan%20for%20Inclusive%20Pharmacy%20Practice%20-%2010%20March.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 39Baqir W, Root G. How to deliver culturally competent healthcare for communities and people with an ethnic minority background. Public Health England. 2021. https://www.rpharms.com/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=QJVxWmgAq14%3D&portalid=0 (accessed March 2024)

- 40Disparities in the Risks and Outcomes of COVID-19. Public Health England. 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f328354d3bf7f1b12a7023a/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 41Workforce Wellbeing Roundtable Report. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2023. https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Workforce%20Wellbeing/Workforce%20Wellbeing%20Roundtable%20Report%20-%20Final.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 42Pharmacy Workforce Race Equality Standard Report. NHS England. 2023. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/pharmacy-workforce-race-equality-standard-report/ (accessed March 2024)

- 43Kubik-Huch RA, Vilgrain V, Krestin GP, et al. Women in radiology: gender diversity is not a metric—it is a tool for excellence. Eur Radiol. 2019;30:1644–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06493-1

- 44NHS Long-term Workforce Plan. NHS England. 2023. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/nhs-long-term-workforce-plan-v1.2.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 45Building bridges: pharmacists reaching out to help their communities. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1211/pj.2023.1.173225