Mclean/Shutterstock.com

It was on 22 March 2020 that Leanne first fell ill with COVID-19.

Other than a brief visit to A&E, following a bout of severe breathlessness, the 40-year-old mother of two — who says she was previously in excellent health — had largely managed her symptoms at home and, by early April 2020, was assured by doctors that she was in recovery.

But then came the “indescribable” headaches, the fluctuating heart rate and — around ten weeks after her initial infection — severe fatigue.

At one point, I was choosing whether to eat or shower — it was that bad

“I could barely function,” she says. “At one point, I was choosing whether to eat or shower — it was that bad.”

Pushing herself beyond an hour or two of activity led to slurred speech and a heavy sensation in her arms and legs. She has also had gastrointestinal issues, leaving her unable to eat many foods. “I couldn’t understand why I wasn’t getting better.”

Six months later, many of the same symptoms persist and Leanne still does not feel safe going outside on her own, in case she passes out.

Shocking as Leanne’s story is, she is not alone.

Thousands of people who had seemingly recovered from COVID-19 are now reporting persistent and even severe symptoms — a condition that sufferers have coined ‘long COVID’. LongCovidSOS, a support group set up by those experiencing the condition, has around 8,000 members, 6,000 of whom are based in the UK.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) are working with the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) to develop a guideline on the effects of long COVID on patients. They define the condition— which they term ‘post-COVID-19 syndrome’ — as signs and symptoms that develop during or following an infection consistent with COVID-19, which continue for more than 12 weeks and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis. They use the term ‘ongoing symptomatic COVID-19’ to describe signs and symptoms of COVID-19 from 4 to 12 weeks.

NICE and SIGN say that long COVID usually presents with clusters of symptoms, often overlapping, which may change over time and can affect any system within the body. They also note that many people with the condition can also experience generalised pain, fatigue, persisting high temperature and psychiatric conditions.

So wide is the range of symptoms experienced, in fact, that it has created ongoing diagnostic uncertainty. In the first dynamic themed review of scientific evidence on the condition, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Centre for Engagement and Dissemination has suggested long COVID may actually be four different syndromes: post-intensive care syndrome; post-viral fatigue syndrome; long-term COVID syndrome; and permanent organ damage, as well as the possibility that some patients may experience more than one condition simultaneously[1]

.

What is clear is that, as COVID-19 infections continue to rise steeply in the UK, cases of long COVID are likely to become increasingly common.

Prevalence of ‘long COVID’

The exact scale and severity of long COVID is the subject of ongoing research. But early indications from some small studies suggest it could be quite common.

In what is thought to be the first peer-reviewed study of the condition, published in JAMA in July 2020, Italian researchers found that 87.4% of patients reported at least one persistent symptom an average of 60 days after their initial COVID-19 diagnosis and 55.0% had three or more persistent symptoms[2]

.

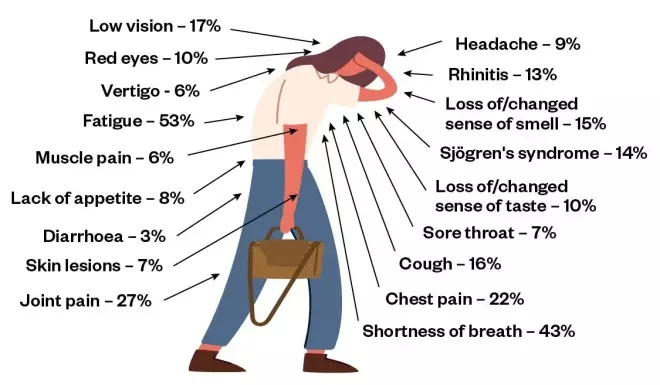

Fatigue, shortness of breath, headaches, and joint and muscular pain are among the most common symptoms, says lead author of the study Angelo Carfi, a clinician at Agostino Gemelli University Hospital in Rome, Italy (see Figure).

Figure: Long COVID symptoms

Source: JAMA 2020;324(6):603-605.

Long COVID usually presents with clusters of symptoms, often overlapping, which can change over time and can affect any system within the body. The first published study of the condition (n=143) suggests that fatigue, shortness of breath, headaches, and joint and muscular pain are among the most common symptoms an average of 60 days (8.5 weeks) after onset of COVID-19.

“The results were a surprise; we didn’t expect such high figures. These were mostly healthy people prior to COVID-19,” he explains.

While Carfi and his team focused solely on patients who had been hospitalised with their infection, it seems long COVID also occurs among those who had milder symptoms.

A preprint of an analysis of data from 4,182 incident cases of COVID-19 logged in the COVID Symptom Study app, which was developed by health science company ZOE in collaboration with scientists at King’s College London, found that around 1 in 7 patients had COVID-19 symptoms lasting for at least 4 weeks, around 1 in 20 were ill for 8 weeks and 1 in 50 experienced symptoms for more than 12 weeks[3]

. It suggested that long COVID affects around 10% of people aged 18-49 years who become unwell with COVID-19, and 22% of those aged 70 years or over.

The researchers also observed that those experiencing long COVID were consistently older, more often female and more likely to require hospital assessment than those in the group reporting symptoms for a short period of time.

More than four million participants have downloaded the COVID Symptom Study app and are using it to regularly report on their health. This is part of efforts to build a more detailed picture of long COVID and how many people it has affected.

The Post-Hospitalisation COVID study (PHOSP-COVID), launched in July 2020 and funded with £8.4m from the NIHR and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), is a long-term research study aiming to recruit 10,000 UK patients who have been hospitalised with COVID-19 to track their recovery over a 12-month period.

The PHOSP-COVID study will develop trials of new strategies for clinical care, including personalised treatments for patients based on the particular disease characteristics they show as a result of having COVID-19.

It is imperative that the needs of this group are addressed, and sufferers given the support they need

Meanwhile, the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC), based at the University of Oxford, is behind a longitudinal observational study aiming to track the long-term health and psychosocial consequences of COVID-19 at serial intervals for up to three to five years after discharge from hospital.

In October 2020, NIHR and UKRI also announced a call for further research projects— to start from 2021 — looking into the longer-term physical and mental effects of COVID in non-hospitalised patients.

However, for those already experiencing long COVID, the prospect of waiting months, or even years, for answers is too much. In an “urgent SOS” to government, members of LongCovidSOS said they were unable to access the right care and felt “abandoned”[4]

.

“It is imperative that the needs of this group are addressed, and sufferers given the support they need,” they wrote.

The effects of long COVID

Although COVID-19 was initially thought to be a respiratory condition characterised by a dry cough and fever, we now know that it affects multiple systems in the body, including the cardiovascular, renal and gastrointestinal systems, and this is also true for long COVID[5]

.

The COVID Symptom Study has shown that some people are experiencing fatigue, headaches, coughs, anosmia, sore throats, delirium and chest pain more than four weeks after first reporting symptoms in the app.

The reasons for these prolonged symptoms are complex, multi-faceted and, as yet, only partially understood.

A report, published by the British Society for Immunology on 13 August 2020, said that the SARS-CoV-2 virus (the virus that causes COVID-19 infection) may cause long-term damage to different organs through a variety of mechanisms; direct effects of viral infection and tissue damage; excessive inflammation and subsequent damage; post-viral autoimmunity; and complications emerging from the formation of blood clots[6]

.

As part of the PHOSP-COVID study, researchers carried out whole-body MRI scans to examine the effects of the virus on the brain and other organs. Addressing the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee on 15 September 2020, Chris Brightling, NIHR senior investigator and clinical professor in respiratory medicine at the University of Leicester, explained that pilot data from the first 50 patients the researchers scanned showed “end-organ damage in the kidneys, liver, lung and heart, but less so in the brain”. This damage affected more than a third of individuals at the two-month point[7]

. Both severe inflammatory responses throughout infection and acute treatment, where damage is caused to the airways by respiratory support equipment, could be contributors, he explained.

In some cases, this damage is leading to potentially severe, long-term conditions.

Long-term effects on major organs

This is a relatively new virus and, as such, we don’t have a good understanding of the cardiovascular implications over the medium nor long term

Among cardiovascular conditions reported are “myocarditis, stress cardiomyopathy and arrythmia, as well as palpitations during recovery,” Sonya Babu-Narayan, consultant cardiologist at the Royal Brompton Hospital, told committee members at the same hearing in September 2020[7]

.

Paul Wright, lead cardiac pharmacist at Barts Health NHS Trust, points out that many questions remain on the long-term cardiovascular impact.

“This is a relatively new virus and, as such, we don’t have a good understanding of the cardiovascular implications over the medium nor long term.

“Does the severity of the infection link into post-viral issues? [Are] there going to be long-term cardiovascular issues in those who are affected with COVID but [who] were asymptomatic?”

Similar questions remain regarding respiratory complications, admits Toby Capstick, consultant pharmacist at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

Post-viral patients have presented with lung fibrosis, a condition caused by damaged or scarred lung tissue, he says, but there is little way of knowing the long-term progression.

“Some people with lung fibrosis [in non-COVID-19 circumstances] can be fairly stable, others have rapidly progressive fibrosis. Whether or not [COVID-19] fits into either of these patterns, or is completely different — only time will tell.”

Alongside the long-term physiological conditions arising from COVID-19, many experts are also warning about the impact of the virus on mental health (see Box).

Box: Impact of COVID-19 on mental health

Harpreet Chana, founder and managing director of the Mental Wealth Academy, which works alongside pharmacists and organisations to improve mental health via self-leadership skills, predicts the UK will face a “tsunami of mental health conditions” in the coming months as a result of COVID-19.

The cumulative impact of loneliness from isolation, stress and trauma — both among those who have suffered from the virus and those who have not — are set to cause a surge in mental health conditions during the winter months, she believes, in the period when seasonal affective disorder already affects up to one in three people in the UK[8]

.

“Loneliness is one of the biggest precursors to depression out there,” she says. “So far, our focus has been on the elderly and the infirm, but we also are now seeing loneliness among younger people [who] may even live with others but are by themselves most of the day, as a result of working from home.”

In addition, she says, there is “the stress of an economic recession, plus the threat of infection. It’s the uncertainty of it all. Not being able to predict events means you lose control, and that loss of control is what people are really struggling with”.

All of this is only compounded by the trauma caused, either directly or indirectly, by the virus itself, stoking high levels of fear, depression and anxiety. “It’s a ticking timebomb,” says Chana.

Providing the support patients need

Many experiencing long COVID argue that more needs to be done to recognise the condition. In a qualitative study published in mid-October 2020, participants with symptoms of long COVID described difficulty in getting GPs to “believe” their condition, a lack of awareness and knowledge of the condition, and challenges in accessing the right care[9]

.

“In the initial wave, there was a fair proportion of GPs that dismissed ‘long COVID’ as anxiety,” says Paul Garner, professor at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine — and someone also experiencing long COVID.

Nobody seems to have access. Doctors don’t have protocols. Referrals are not happening. It is chaos

Regarding the emergent heart symptoms, Garner says that doctors do not know how to treat or investigate them, and quite often they dismiss them, although he says they are “learning rapidly”.

However, Garner says he does not know how to access existing rehabilitative services.

“Nobody seems to have access. Doctors don’t have protocols. Referrals are not happening. It is chaos.”

The need for multidisciplinary services that incorporate a wide range of specialisms to reflect the varied impact of long COVID is largely agreed upon by experts.

There are some regions where this type of service is already available. In May 2020, the NHS Seacole Centre opened in Surrey: a multidisciplinary rehabilitation service for patients recovering from the long-term effects of COVID-19, with more than 100 staff, including nurses, physiotherapists and pharmacists.

In Sheffield, a research and innovation unit (RICOVR) has been set up to identify effective methods of treating patients with long COVID symptoms, particularly focusing on physical activity. The service says it plans to draw on expertise in health, behavioural science, engineering, the arts, software design, robotics, sport and exercise science.

And, at the beginning of October 2020, Simon Stevens, chief executive of NHS England, announced that £10m was to be invested in additional local funding in 2020 to help “kick start” and designate long COVID clinics “in every area across England”, to complement existing primary, community and rehabilitation care.

At these clinics, respiratory consultants, physiotherapists, GPs and other specialists will help to assess, diagnose and treat the thousands of sufferers who have reported long COVID symptoms.

The announcement has been welcomed by LongCovidSOS. “We believe that multidisciplinary clinics are essential for the assessment, treatment and rehabilitation of the huge numbers of people still suffering the effects of COVID-19,” says LongCovidSOS member Onidine Sherwood.

“We feel strongly that the clinics should be truly multidisciplinary, based on a ‘one-stop shop’ format,” she adds. “We want to avoid a situation where people are referred to specialists but then find themselves at the back of long ‘non-urgent’ waiting lists.”

Also part of NHS England’s long COVID “package” is the online rehabilitation service

Your Covid Recovery. Launched in July 2020, the service is being delivered in two phases. First — and currently live — is a website with extensive resources for those with long COVID, as well as their family and friends, on how to self-manage symptoms and when to seek further support.

The second phase of the project, being developed this autumn, will take the form of an on-demand service, in which patients will be offered a consultation with nurses, physiotherapists and psychologists, followed by a bespoke package of aftercare, lasting up to 12 weeks.

All of this work will be overseen by a new NHS England long COVID taskforce that will include long COVID patients, medical specialists and researchers.

Whatever shape future care pathways may take, it is clear that the burden on existing healthcare services in the community will increase as a result of long COVID.

As the NHS summed up in its June 2020 report on aftercare of inpatients recovering from COVID-19: “Community health services … will need to support the increase in patients … that need ongoing health support, both physically and mentally. Meeting these challenges will be a joint endeavour”[10]

.

For those like Leanne, the ask is simple, if not easy to deliver. “We want recognition, research and rehabilitation,” she sums up.

“With cases on the rise, long COVID will also be on the rise, and this is only going to become a bigger and bigger problem.”

References

[1] National Institute for Health Research. 2020. doi: 10.3310/themedreview_41169

[2] Carfi A, Bernabei R, Landi F et al. JAMA 2020;324(6):603-605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603

[3] Sudre C, Murray B, Varsavsky T et al. Preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.19.20214494

[4] LongCovidSOS. 2020. Available at: https://3ca26cd7-266e-4609-b25f-6f3d1497c4cf.filesusr.com/ugd/8bd4fe_e3779d8fa84c4c32bbd8ed43d70cd3cf.pdf?index=true (accessed November 2020)

[5] Gupta A, Madhavan M & Landry D. Nature Medicine 2020;26:1017-1032. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3

[6] British Society for Immunology. 2020. Available at: https://www.immunology.org/sites/default/files/BSI_Briefing_Note_August_2020_FINAL.pdf (accessed November 2020)

[7] UK Parliament. 2020. Available at: https://committees.parliament.uk/event/1910/formal-meeting-oral-evidence-session/ (accessed November 2020)

[8] Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2015. Available at: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/problems-disorders/seasonal-affective-disorder-(sad) (accessed November 2020)

[9] Kingstone T, Taylor A, O’Donnell et al. BJGP Open 2020. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101143

[10] NHS England. 2020. Available at: https://www.pcrs-uk.org/sites/pcrs-uk.org/files/nhs-aftercarecovid.pdf (accessed November 2020)