SEBASTIAN KAULITZKI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Outline the normal structure, function and regulation of the adrenal glands;

- Describe the pathophysiology of adrenal insufficiency;

- Evaluate treatment options for patients with adrenal insufficiency;

- Outline the safety considerations that pharmacists should be aware of when treating patients with adrenal insufficiency.

The term ‘adrenal insufficiency’ refers to a group of conditions that all result from a defect along the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and subsequent deficiency in one or more of the adrenal hormones, primarily cortisol. It can be divided into primary, secondary and tertiary forms, depending on the underlying cause1.

Autoimmune primary adrenal insufficiency, commonly known as Addison’s disease, can occur at any age, but most often presents in patients between the ages of 20 years and 50 years2–4. Although a relatively rare condition, there are approximately 9,000 patients living with primary adrenal insufficiency and around 320 new diagnoses per year in the UK2,4. Secondary adrenal insufficiency is associated with impaired pituitary function. Tertiary adrenal insufficiency is usually the result of exogenous glucocorticoid therapy, especially when the therapy is prolonged. Data show that approximately 1% of the UK population are taking oral glucocorticoid therapy at any given time5,6.

Regardless of the underlying cause, all patients with adrenal insufficiency are at risk of a life-threatening adrenal crisis if their steroid therapy is interrupted or the condition is not managed appropriately during periods of physiological stress (such as intercurrent illness, trauma or surgery)7,8. In 2020, a national patient safety alert highlighted the need to ensure that patients with adrenal insufficiency are managed appropriately after 4 deaths, 4 critical-care admissions and approximately 320 other patient-safety incidents involving steroid replacement were identified over a two-year period9. The alert also highlighted that, although there are many resources to support clinicians in this area, both specialists and patients reported that some clinical staff were unaware of the risks of inadequate management and of how an adrenal crisis should be managed9. As a result, it is crucial that pharmacists across all sectors are alert to the risks of inadequate management of adrenal insufficiency, whether that owes to dispensing and supply issues, continuity of care across care interfaces, or in the acute setting.

Anatomy and function of the adrenal glands

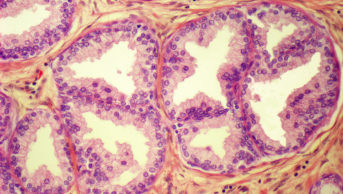

The adrenal glands are two triangular organs, weighing approximately 4–5g each, situated on the top of each kidney and consisting of two distinct areas, the outer cortex and the inner medulla10. The outer cortex, which represents approximately 90% of the mass of the glands, is where the hormones associated with adrenal insufficiency are synthesised and secreted, and the inner medulla is responsible for the synthesis and secretion of catecholamines10,11.

The adrenal cortex is split into three distinct layers, each responsible for the secretion of different hormones and each under control of either the HPA axis via adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) or the renin-angiotensin system (RAS)10,12. This is summarised in Figure 1.

Once secreted, cortisol has a wide range of metabolic actions within the body involving glucose (driving hyperglycaemia), protein catabolism and the redistribution of fats. It also has regulatory functions involving negative feedback: inhibiting the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and ACTH, vasoconstriction, bone metabolism and inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions13. Aldosterone acts primarily in the distal tubules of the nephrons to promote sodium and water retention and potassium excretion13. Although adrenal androgens contribute to the development of secondary sexual characteristics, maturation of the reproductive organs, sexual function, a feeling of wellbeing and increased physical vigour, their effect is small when compared to gonadal androgens and sex hormones14.

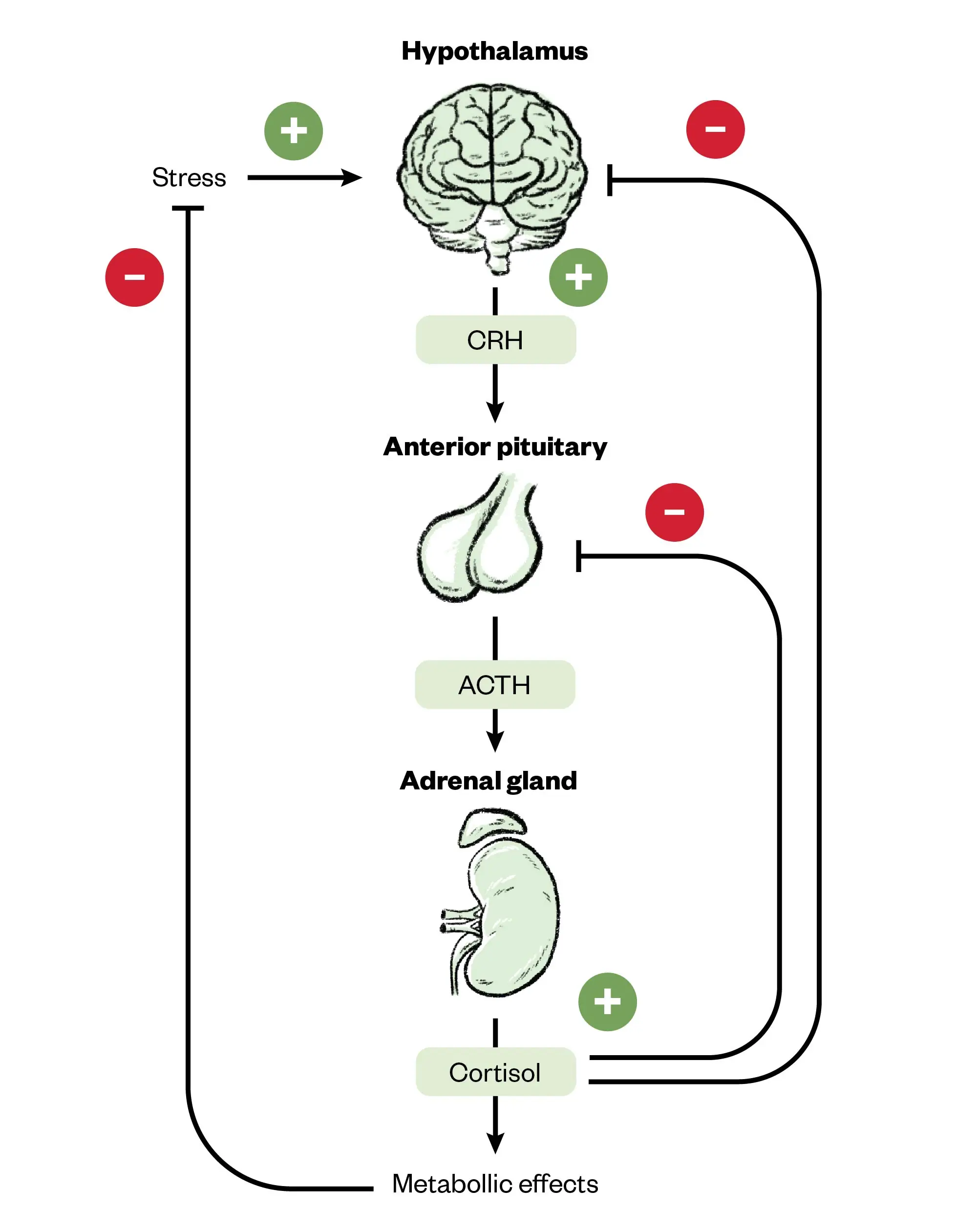

As outlined in Figure 1 above, the secretion of cortisol and androgens is controlled by the HPA axis, whereas the secretion of aldosterone is primarily under the control of the RAS. In the HPA axis, the hypothalamus secretes CRH in response to stress, circadian rhythm and low cortisol. CRH then stimulates the release of ACTH from the anterior pituitary, which in turn stimulates the secretion of cortisol and androgens from the adrenal cortex. Negative feedback in the form of increasing cortisol levels acts to inhibit the release of both CRH and ACTH, with ACTH also acting to inhibit the release of CRH12,13,15.

Figure 2 summarises the functionality of the HPA axis and its role in regulating cortisol secretion.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

ACTH: adrenocorticotropic hormone; CRH: corticotropin-releasing hormone

Pathophysiology

Primary adrenal insufficiency is caused by a defect in the adrenal cortex itself, most commonly resulting from either autoimmune destruction, adrenoleukodystrophy or congenital adrenal hyperplasia2,10,16. Autoimmune primary adrenal insufficiency has a significant genetic component and a high degree of heritability, as well as being associated with other autoimmune endocrinopathies, such as thyroid disorders and type 1 diabetes mellitus1,17. Women are at slightly higher risk than men, although the difference is small17,18. Infections associated with primary adrenal insufficiency include tuberculosis, HIV and cytomegalovirus2,10. As a consequence of the gland itself being affected, patients with primary adrenal insufficiency become deficient in all of the hormones usually secreted from the cortex.

Secondary adrenal insufficiency results from inadequate secretion of ACTH from the anterior pituitary. It can be caused by pituitary tumours, irradiation, infection, pituitary apoplexy or genetic disorders1,10,16. The most common cause is a pituitary (or nearby) tumour that impairs pituitary function itself, or its treatment does1. The result is a deficiency in the secretion of ACTH and, therefore, only hormones under the direct control of ACTH (cortisol and, to a lesser extent, androgens) are affected1,10. The adrenal gland itself is not defective and so the release of aldosterone, which is primarily under the control of the RAS, remains unaffected13. Secondary adrenal insufficiency can present in the context of hypopituitarism, where there is a deficiency in the production of other pituitary hormones, such as growth hormone, gonadotrophins and thyroid-stimulating hormone1.

Tertiary adrenal insufficiency is caused by suppression of CRH secretion from the hypothalamus. The most common cause is long-term use of physiological or supraphysiological doses of exogenous glucocorticoids1,10,12. These patients are not typically symptomatic of adrenal insufficiency, as their cortisol requirements are being met exogenously, but become so once the glucocorticoids are withdrawn. In patients with adrenal overactivity (Cushing’s syndrome), elevated levels of endogenous cortisol suppress the HPA axis in the same manner10.

In addition to glucocorticoids, other medicines associated with adrenal insufficiency include — but are not limited to — CYP3A4 inducers, such as phenytoin and rifampicin (which induce the metabolism of cortisol), checkpoint inhibitors, opioids and lithium1,12,19,20. Potent inhibitors of CYP3A4, such as ketoconazole, fluconazole and antiretrovirals, can inhibit the metabolism of cortisol, elevating levels and leading to cushingoid features with subsequent suppression of the HPA axis1. This effect has been observed even with inhaled corticosteroids in patients treated with ritonavir21.

Identifying patients at risk of tertiary adrenal insufficiency can be challenging, but there are guidelines available from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Specialist Pharmacy Service and the Society for Endocrinology detailing who is at risk and how they should be managed safely5,20. Any patient taking glucocorticoids at a physiological equivalent dose or above (approximately 3–5mg of prednisolone per day for those aged 16 years or over) for longer than 4 weeks (or 3 weeks if aged under 16 years) is at risk of adrenal insufficiency5,20,22. Guidelines also highlight that patients taking multiple short courses of glucocorticoids are also at risk, although they acknowledge that this is an area where there is little published evidence5,23. There is also a potential risk with other forms of exogenous glucocorticoids, such as intra-articular, inhaled, nasal and topical administration5.

Symptoms and presentation of adrenal insufficiency

The symptoms of adrenal insufficiency are often vague and non-specific, resulting in a challenging and often delayed diagnosis. In 2010, results from a cross-sectional study showed that fewer than 30% of women and 50% of men were diagnosed within six months of symptom onset, while 20% experienced symptoms for over five years before diagnosis24,25. A consequence of such delays is that some patients present with an acute life-threatening adrenal crisis before a diagnosis is made24. NICE guidance recommends that adrenal insufficiency should be considered in patients with unexplained hyperpigmentation, or when there is no other clinical explanation for the presence of one or more of the signs and symptoms listed in Table 120.

Diagnosis and assessment of adrenal insufficiency

Once suspected, adrenal insufficiency can be confirmed by assaying morning cortisol levels between the hours of 08:00 and 09:00. Random cortisol assays are not recommended20. The results of this assay should then guide decisions on referral, further investigation and treatment as outlined below in Table 220.

The short Synacthen test can be used to confirm the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. It involves the assaying of baseline cortisol and ACTH, followed by the intramuscular or IV administration of 250 micrograms tetracosactide, followed by repeat cortisol assays after 30 minutes and 60 minutes26. Tetracosactide is a synthetic form of ACTH and acts to stimulate the zona fasciculata to release cortisol27. A patient is considered to have demonstrated a normal adrenal response if they achieve a stimulated plasma cortisol of 450nmol/L26. Primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency can be distinguished by the patient’s ACTH values, with levels >200ng/L indicating primary adrenal insufficiency and ACTH levels <10ng/L indicating secondary adrenal insufficiency26. It should be noted that both the cortisol and ACTH values quoted here may differ from those at other centres depending on the assay used, and local protocols should be followed. Although the timing of the test is not critical, it is generally performed early in the day, with most UK centres recommending a 09:00 or morning test24,28,29.

Other methods exist to diagnose secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency (central adrenal insufficiency), such as insulin tolerance and glucagon stimulation tests, but these are only performed under specialist supervision30. The short Synacthen test is considered the ‘gold standard’ diagnostic test and is recommended for all patients with suspected primary adrenal insufficiency by the Endocrine Society, despite there being some ongoing debate about exact cut-off values24.

Pharmacists should be aware that there are medicines that can interfere with the accuracy of this test. Patients taking physiological doses of glucocorticoids should not be tested for adrenal insufficiency and anyone taking oral oestrogen should stop taking it for six weeks prior to measuring serum cortisol, owing to its tendency to falsely elevate cortisol levels20,31.

Management of adrenal insufficiency

As primary adrenal insufficiency results in the underproduction of all the adrenal hormones, patients need to be treated with both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement10,12. However, patients with central adrenal insufficiency do not require mineralocorticoids, because these are not under the control of the HPA axis10,12. Treatment with steroid hormones is usually a lifelong commitment for patients with adrenal insufficiency, except for those with tertiary adrenal insufficiency, which is most commonly associated with long-term use of systemic glucocorticoids.

For patients aged 16 years and above, the first-line glucocorticoid is immediate-release hydrocortisone at an initial dose of 15–25mg daily in two or three divided doses20,24. The largest portion of the daily dose should be given upon waking, with the rest either in the early afternoon (for twice-daily dosing) or at lunchtime/later afternoon (for thrice-daily dosing) to mimic the natural diurnal release of cortisol20,24,30. The use of higher-frequency regimens (e.g. four times daily) may be beneficial in individual cases24.

For patients with poor adherence, longer-acting glucocorticoids (e.g. prednisolone), given at a dose of 3–5mg per day, can be considered20,24. A modified-release hydrocortisone preparation, such as Plenadren (Takeda UK), is also an option to support adherence, although it should not be considered first line20. Plenadren tablets have an outer layer that provides an immediate release of hydrocortisone and an inner core that provides an extended release designed to mimic the normal diurnal secretion of cortisol32. Efmody (Diurnal) is another brand of modified-release hydrocortisone licensed for the treatment of congenital adrenal hyperplasia in patients aged 12 years and over33.

It is worth noting that the release profiles, indications and dosing regimens for Plenadren and Efmody are very different and the two brands are not interchangeable.

The uptake of modified-release hydrocortisone in the UK has been limited, but some advocate for its use in specific patients as it may have benefits in certain situations1,34,35. Recognising that adherence to multiple daily doses of hydrocortisone can be challenging for some, especially younger people, NICE has now endorsed the use of modified-release hydrocortisone as an alternative therapy20.

It should be noted that the drug and dosing recommendations discussed above differ for patients aged under 16 years and that pregnant patients frequently require higher doses, especially in the third trimester20.

Mineralocorticoid replacement is only required in patients with primary adrenal insufficiency, since aldosterone release is predominantly under the control of the RAS rather than the HPA axis10,12. Fludrocortisone at an initial dose of 50–100 micrograms daily without salt restriction is recommended, with doses adjusted based on salt craving, postural hypotension, oedema and serum electrolytes24. A dose of 50–200 micrograms daily is sufficient for the majority of patients, but higher doses may be needed in younger and more physically active individuals20,24. Fludrocortisone is usually taken as a single dose in the morning to reflect the naturally higher levels of aldosterone at this time of day36. Patients taking prednisolone and dexamethasone may require higher doses of fludrocortisone, owing to their reduced mineralocorticoid activity relative to hydrocortisone24,37. Neonates and children are less sensitive to mineralocorticoids so may require higher doses relative to adults24.

Patients with adrenal insufficiency are deficient in adrenal androgens, but the benefits of androgen replacement are less well defined than the benefits of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids38,39. In 2009, results from a meta-analysis of the effect of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) treatment on quality of life in women revealed that, while DHEA replacement may improve quality of life and depression in women with adrenal insufficiency, there was insufficient evidence to support its routine use40. Furthermore, there are unquantified concerns about the risk of oestrogen-sensitive cancers, venous thromboembolism and cardiovascular disease with the use of DHEA1,39.

The latest NICE guidelines make no recommendations regarding androgen replacement, but the Endocrine Society suggests considering a trial of DHEA replacement in women with adrenal insufficiency experiencing low libido, depressive symptoms and/or low energy levels, despite their glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement being optimised20,24. This should be trialled for six months and stopped if the patient does not experience a sustained benefit24.

The management of glucocorticoid-induced tertiary adrenal insufficiency is different to that described above. In these patients, neither the HPA axis nor the adrenal glands themselves are dysfunctional per se, but the long-term use of physiological or supraphysiological doses of exogenous glucocorticoids results in suppression of the HPA axis via the negative feedback mechanisms described above6,12,13,15. Over a prolonged period, this results in reduced responsiveness of the anterior pituitary and atrophy of the adrenal cortex6. Once exogenous glucocorticoids are withdrawn, there is a resurgence in ACTH-mediated stimulation of the adrenal cortex which, in most instances, will recover given sufficient time6.

The time taken to fully recover is dependent on overall exposure, the potency and dose of the glucocorticoid used, duration of treatment and individual susceptibility6. The latest guidelines from the European Society of Endocrinology and Endocrine Society recommend that glucocorticoids should be tapered down, with the rate depending on the current dose, provided they are no longer required for management of the underlying condition6. Patients on higher doses (>30mg prednisolone per day) can have their dose reduced in larger decrements, but the rate of tapering should be slowed once they approach a physiological dose. At this point, recovery of the HPA axis is possible, with further — but more cautious — tapering and/or assessment of the HPA axis performed6. Table 3 outlines the suggested tapering regime6.

It is important to note that glucocorticoid withdrawal comes with a potentially life-threatening risk of an acute adrenal crisis41. For patients on longer-acting glucocorticoids, such as dexamethasone, it is recommended that (if appropriate) they be switched to a shorter-acting steroid, such as prednisolone or hydrocortisone, when tapering, because longer-acting versions exert a more sustained suppressive effect on the HPA axis6,42.

In patients who have received a short course of glucocorticoids (<3–4 weeks), there is no need to taper, and therapy can be stopped abruptly, regardless of dose, without any further testing as the risk of HPA axis suppression is low6.

Management of acute adrenal crisis

Patients with adrenal insufficiency are at risk of life-threatening adrenal crises. These occur because of the adrenal glands’ inability to produce sufficient cortisol in response to an acute increase in demand, such as physiological or psychological stress1,24. The primary clinical features are hypotension and dehydration, but there is a long list of other, often vague, signs and symptoms including (but not limited to) fatigue, dizziness, collapse, confusion, abdominal pain, vomiting, muscle cramps and, in severe cases, hypovolaemic shock24,43. Potential biochemical findings include hyponatraemia, hyperkalaemia (in primary adrenal insufficiency), pre-renal acute kidney injury, normochromic anaemia and hypoglycaemia44.

Prompt recognition and management can save lives; therefore, once suspected, patients should be treated with an immediate parenteral dose of 100mg hydrocortisone. In hospital, this is usually given by IV injection but patients and carers in other contexts and settings can self-administer this via intramuscular (IM) injection, using their emergency management kit20,44. An emergency management kit contains hydrocortisone for intramuscular injection that can be given by anyone, including the person with adrenal insufficiency, when adrenal crisis is suspected20.

This should be followed by the administration of 200mg hydrocortisone every 24 hours, either by continuous infusion or intermittent infusions of 50mg every 6 hours20,24,44. It is important to emphasise to both patients and clinicians that there is no risk of overdose from hydrocortisone in an emergency20. Immediate rehydration with 1.0L sodium chloride 0.9% given over 30 minutes, followed by further IV fluids, is also essential20,44. Further fluid requirements should be determined by the patient’s haemodynamic parameters and their electrolyte status, but is usually in the region of 4.0–6.0L in 24 hours20,44. IV hydrocortisone and fluid replacement should continue until the patient is stable and able to take their glucocorticoids orally20,44. As above, these recommendations relate specifically to the treatment of adult patients.

It is recommended to use increased oral doses (sick-day dosing) until the underlying cause of the adrenal crisis has been rectified and the patient is stable, after which they can be tapered back to their usual hydrocortisone dose (or started in the case of newly diagnosed patients)20. Sick-day dosing is covered further under ‘Patient counselling and support’.

Fludrocortisone is not required while the patient is receiving ≥50mg hydrocortisone in 24 hours44.

The prevention of adrenal crisis in patients in the peri-operative period is beyond the scope of this article; however, the Association of Anaesthetists, Royal College of Physicians and the Society for Endocrinology have produced joint guidelines on this, and further information is also available in the Handbook of Perioperative Medicines8,45.

Monitoring of patients with adrenal insufficiency

NICE guidelines recommend that patients with adrenal insufficiency are offered ongoing reviews by a specialist team, the frequency of which will depend on the patient’s clinical and individual needs20. Patient age, growth rate, changes in family and personal circumstances, transition between services, concern about adherence or the ability to safely manage their condition, and vulnerability are a few of the factors that should be considered20. During these reviews, clinicians should enquire about psychological wellbeing, the patient’s understanding of the condition, adherence, use of increased doses during intercurrent illness, their understanding of the sick-day rules and any hospital admissions20. The Society for Endocrinology has produced a consultation reference guide for adult patients with primary adrenal insufficiency that serves as a useful aide memoire for clinicians supporting patients at diagnosis and follow-up46.

Although glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids are associated with a significant number of side effects, most patients with adrenal insufficiency do not experience the long-term adverse effects typically associated with these drugs. This is because they are being used at physiological replacement doses rather than the much higher pharmacological doses used to treat allergic or inflammatory conditions, although some patients do report that they experience gastric irritation with hydrocortisone47. The short-term use of higher doses, such as those seen in acutely unwell patients, is unlikely to be associated with any longer-term effects. Despite this, clinicians should be alert to the signs of over- and under-replacement and adjust doses accordingly (see Table 4)20.

The Endocrine Society recommends monitoring glucocorticoid replacement using clinical assessment and response to therapy only and not hormonal monitoring24. This recommendation notwithstanding, cortisol day curves are available to test the effectiveness of replacement therapy in patients who remain symptomatic despite conventional replacement regimes and can help identify optimal treatment26,48. Monitoring of salt craving, blood pressure, postural hypotension, oedema and serum electrolytes is recommended to guide dosing for mineralocorticoid replacement24. In the event of hypertension developing, the dose of fludrocortisone can be reduced and appropriate antihypertensive therapy started if indicated24,49.

Patient counselling and support

Acute adrenal crises can often be prevented by ensuring patients adhere to sick-day rules, therefore it is important that patients are familiar with these. Patients should double their usual hydrocortisone dose if they experience a fever, are unwell with a bad cold, flu, diarrhoea or other infection, or if they suffer a significant injury, ensuring that they are taking a minimum of 40mg per day20,50. Patients taking modified-release hydrocortisone should temporarily switch to standard-release tablets20,50. Patients taking prednisolone should increase their dose to at least 10mg per day (in a single or split dose), but there is generally no need to increase their dose if already taking ≥10mg20. If severely ill and still feeling unwell on prednisolone 10mg, patients should increase it again to 15–20mg/day in divided doses50. A temperature of >39oC indicates a more severe infection and the patient should consider seeking immediate medical advice especially if deteriorating50. This sick-day dosing should continue for at least 48 hours or until they are feeling better, but medical advice should be sought if it persists beyond 48 hours. If on antibiotics, sick-day dosing should continue until the course is completed unless on a particularly prolonged course where earlier tapering may be appropriate50.

In the event of vomiting within 30 minutes of an oral dose, a repeat double dose should be taken and, if vomiting persists, the administration of hydrocortisone 100mg by IM injection should follow20.

In the event of psychological stress, sick-day dosing should be considered for 24–48 hours, although IM hydrocortisone may be required in the event of a severe mental health crisis20.

Patients with primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency should be issued with at least two emergency kits containing either pre-mixed hydrocortisone sodium phosphate (100mg/mL) or hydrocortisone sodium succinate powder (100mg) with water for reconstitution20. They should also be given the necessary sundries, including needles, syringes and instructions on how to administer. Training should also be provided20. The Addison’s Disease Self Help Group has produced materials, such as leaflets and videos, to support patients with this51–53. It should be noted that these sundries are generally not available from community pharmacies or primary care and should be provided by the patient’s specialist endocrine team. The benefits of emergency kits in tertiary adrenal insufficiency are less clear and this is reflected in the wording used within NICE’s recommendation to ‘consider’ providing them to this group of patients20.

Patients should also be provided with an NHS steroid emergency card or British Society of Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes emergency steroid card, depending on their age, and informed about other means of alerting others of their diagnosis, such as medical-alert jewellery9,20,54,55.

Despite the wealth of information available to patients, it is important to acknowledge that some patients do not always apply their existing knowledge to manage periods of illness or stress56. Healthcare professionals should make every contact count and initiate robust conversations about sick-day rules and the importance of medication adherence, supplemented with appropriate training, written materials and behavioural change interventions, to keep these patients safe.

Best practice points

Adrenal insufficiency is a serious, long-term medical condition that can be challenging for patients to manage, especially in times of illness or stress. If untreated (or inadequately treated) it can be fatal and it is essential that healthcare professionals involved in the care of these patients are aware of how they should be managed.

Pharmacists working across different sectors can support this in several ways, including:

- Undertaking timely and thorough medicines reconciliation upon care transfer to avoid delayed or omitted doses of steroids. Practically this means within 24 hours of a hospital admission or transfer to a care home or intermediate care facility and within one week of discharge from hospital57,58;

- Ensuring patients are provided with an adequate supply of steroid medication, including sufficient spare oral and parenteral doses to manage periods of intercurrent illness. This includes ensuring that patients on modified-release hydrocortisone are also provided with a supply of standard-release tablets for use in an emergency;

- Providing appropriate counselling on topics, such as sick-day rules, and signposting patients to additional support materials such as the Addison’s Disease Self Help Group and the Pituitary Foundation;

- Supporting their organisation to adhere to national patient-safety alerts and ensuring that patients are supplied with steroid emergency cards and written information9;

- Identifying patients who may be at risk of tertiary adrenal insufficiency on the basis of their medication history, taking into account any recently discontinued medicines5;

- Educating other healthcare professionals on the management of the condition.

- 1.Husebye ES, Pearce SH, Krone NP, Kämpe O. Adrenal insufficiency. The Lancet. 2021;397(10274):613-629. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00136-7

- 2.Barthel A, Benker G, Berens K, et al. An Update on Addison’s Disease. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2018;127(02/03):165-175. doi:10.1055/a-0804-2715

- 3.Pearce JMS. Thomas Addison (1793-1860). J R Soc Med. 2004;97(6):297-300. doi:10.1177/014107680409700615

- 4.Diagnosing Addison’s: a guide for GPs. Addison’s Clinical Advisory Panel. 2020. Accessed November 2024. https://www.addisonsdisease.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=73780d5d-8662-4bb0-980a-1a4b1cc9a368

- 5.Erskine D, Simpson H. Exogenous steroids treatment in adults. Adrenal insufficiency and adrenal crisis – who is at risk and how should they be managed safely. Society for Endocrinology . 2021. Accessed November 2024. https://www.endocrinology.org/media/4091/spssfe_supporting_sec_-final_10032021-1.pdf

- 6.Beuschlein F, Else T, Bancos I, et al. European Society of Endocrinology and Endocrine Society Joint Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and therapy of glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2024;190(5):G25-G51. doi:10.1093/ejendo/lvae029

- 7.Simpson H, Tomlinson J, Wass J, Dean J, Arlt W. Guidance for the prevention and emergency management of adult patients with adrenal insufficiency. Clinical Medicine. 2020;20(4):371-378. doi:10.7861/clinmed.2019-0324

- 8.Woodcock T, Barker P, Daniel S, et al. Guidelines for the management of glucocorticoids during the peri‐operative period for patients with adrenal insufficiency. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(5):654-663. doi:10.1111/anae.14963

- 9.Steroid emergency card to support early recognition and treatment of adrenal crisis in adults . NHS England. 2020. Accessed November 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/NPSA-Emergency-Steroid-Card-FINAL-2.3.pdf

- 10.Paun D, Cianci P, Restini E. Oxford Handbook of Endocrinology and Diabetes. Oxford University Press; 2014.

- 11.Loreta Păun D, Cianci P, Restini E, eds. Adrenal Glands – The Current Stage and New Perspectives of Diseases and Treatment. Published online January 31, 2024. doi:10.5772/intechopen.102209

- 12.Martin-Grace J, Dineen R, Sherlock M, Thompson CJ. Adrenal insufficiency: Physiology, clinical presentation and diagnostic challenges. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2020;505:78-91. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.01.029

- 13.Ha CE, Bhagavan N. Endocrine Metabolism III. In: Essentials of Medical Biochemistry. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2015:559-575. Accessed November 2024. https://shop.elsevier.com/books/essentials-of-medical-biochemistry/ha/978-0-12-416687-5

- 14.Alemany M. The Roles of Androgens in Humans: Biology, Metabolic Regulation and Health. IJMS. 2022;23(19):11952. doi:10.3390/ijms231911952

- 15.Leistner C, Menke A. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and stress. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Published online 2020:55-64. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-64123-6.00004-7

- 16.Hahner S, Ross RJ, Arlt W, et al. Adrenal insufficiency. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1). doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00252-7

- 17.Husebye ES, Anderson MS, Kämpe O. Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndromes. Ingelfinger JR, ed. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1132-1141. doi:10.1056/nejmra1713301

- 18.Dalin F, Nordling Eriksson G, Dahlqvist P, et al. Clinical and immunological characteristics of Autoimmune Addison’s disease: a nationwide Swedish multicenter study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. Published online November 21, 2016:jc.2016-2522. doi:10.1210/jc.2016-2522

- 19.Raschi E, Fusaroli M, Massari F, et al. The Changing Face of Drug-induced Adrenal Insufficiency in the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2022;107(8):e3107-e3114. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgac359

- 20.Adrenal insufficiency: identification and management [NG243]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2024. Accessed November 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng243

- 21.Saberi P, Phengrasamy T, Nguyen D. Inhaled corticosteroid use in <scp>HIV</scp>‐positive individuals taking protease inhibitors: a review of pharmacokinetics, case reports and clinical management. HIV Medicine. 2013;14(9):519-529. doi:10.1111/hiv.12039

- 22.Sagar R, Mackie S, W. Morgan A, Stewart P, Abbas A. Evaluating tertiary adrenal insufficiency in rheumatology patients on long‐term systemic glucocorticoid treatment. Clinical Endocrinology. 2021;94(3):361-370. doi:10.1111/cen.14405

- 23.Fleishaker DL, Mukherjee A, Whaley FS, Daniel S, Zeiher BG. Safety and pharmacodynamic dose response of short-term prednisone in healthy adult subjects: a dose ranging, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12891-016-1135-3

- 24.Bornstein SR, Allolio B, Arlt W, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2016;101(2):364-389. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1710

- 25.Bleicken B, Ventz M, Quinkler M, Hahner S. Delayed Diagnosis of Adrenal Insufficiency Is Common: A Cross-Sectional Study in 216 Patients. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2010;339(6):525-531. doi:10.1097/maj.0b013e3181db6b7a

- 26.Endocrine bible. Imperial Centre for Endocrinology. 2023. Accessed November 2024. https://imperialendo.co.uk/Bible2023.pdf

- 27.Synacthen ampoules 250 micrograms . Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed November 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10822/smpc#gref

- 28.Chatha KK, Middle JG, Kilpatrick ES. National UK audit of the Short Synacthen® Test. Ann Clin Biochem. 2010;47(2):158-164. doi:10.1258/acb.2009.009209

- 29.Bhansali A, Subrahmanyam K, Talwar V, Dash R. Plasma cortisol response to 1 microgram adrenocorticotropin at 0800 h & 1600 h in healthy subjects. Indian J Med Res. 2001;114:173-176. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12025258

- 30.Grossman AB. The Diagnosis and Management of Central Hypoadrenalism. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;95(11):4855-4863. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0982

- 31.Lewis A, Thant AA, Aslam A, Aung PPM, Azmi S. Diagnosis and management of adrenal insufficiency. Clinical Medicine. 2023;23(2):115-118. doi:10.7861/clinmed.2023-0067

- 32.Plenadren 5mg modified release tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed November 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5127/smpc

- 33.Efmody 5 mg modified release hard capsules. LINK NOT WORKING – suggested ref link in text. MHRA Products. https://mhraproducts4853.blob.core.windows.net/docs/f3b0ea7e21dac0a38b94071d810c4b3dafa77fcb

- 34.Stewart PM. Modified-Release Hydrocortisone: Is It Time to Change Clinical Practice? Journal of the Endocrine Society. 2019;3(6):1150-1153. doi:10.1210/js.2019-00046

- 35.Isidori AM, Venneri MA, Graziadio C, et al. Effect of once-daily, modified-release hydrocortisone versus standard glucocorticoid therapy on metabolism and innate immunity in patients with adrenal insufficiency (DREAM): a single-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2018;6(3):173-185. doi:10.1016/s2213-8587(17)30398-4

- 36.Williams GH, Cain JP, Dluhy RG, Underwood RH. Studies of the control of plasma aldosterone concentration in normal man. J Clin Invest. 1972;51(7):1731-1742. doi:10.1172/jci106974

- 37.Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, et al. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. All Asth Clin Immun. 2013;9(1). doi:10.1186/1710-1492-9-30

- 38.Kumar R, Wassif WS. Adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Pathol. 2022;75(7):435-442. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2021-207895

- 39.Wierman ME, Arlt W, Basson R, et al. Androgen Therapy in Women: A Reappraisal: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014;99(10):3489-3510. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-2260

- 40.Alkatib AA, Cosma M, Elamin MB, et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials of DHEA Treatment Effects on Quality of Life in Women with Adrenal Insufficiency. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2009;94(10):3676-3681. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-0672

- 41.Dinsen S, Baslund B, Klose M, et al. Why glucocorticoid withdrawal may sometimes be as dangerous as the treatment itself. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2013;24(8):714-720. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2013.05.014

- 42.Crowley RK, Argese N, Tomlinson JW, Stewart PM. Central Hypoadrenalism. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014;99(11):4027-4036. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-2476

- 43.Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, et al. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2014;170(3):G1-G47. doi:10.1530/eje-13-1020

- 44.Arlt W, __. SOCIETY FOR ENDOCRINOLOGY ENDOCRINE EMERGENCY GUIDANCE: Emergency management of acute adrenal insufficiency (adrenal crisis) in adult patients. Endocrine Connections. 2016;5(5):G1-G3. doi:10.1530/ec-16-0054

- 45.Handbook of perioperative medicines. UK Clinical Pharmacy Association. Accessed November 2024. https://periop-handbook.ukclinicalpharmacy.org

- 46.Consultation reference guide for adult patients with Addison’s disease (AD). Society for Endocrinology. April 2023. Accessed November 2024. https://www.endocrinology.org/media/zmnbs40w/addison-s-disease_-consultation-reference-guide_-final_-april-2023.pdf

- 47.Managing your Addison’s. Addison’s Clinical Advisory Panel. 2019. Accessed November 2024. https://www.addisonsdisease.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=9042d6a8-d40e-491d-a548-4974834f6ee4

- 48.Howlett TA. An Assessment of Optimal Hydrocortisone Replacement Therapy. Clinical Endocrinology. 1997;46(3):263-268. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.1340955.x

- 49.Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management [NG136]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2019. Accessed November 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136

- 50.Sick day rules. Addison’s Disease Self Help Group. Accessed November 2024. https://www.addisonsdisease.org.uk/newly-diagnosed-sick-day-rules

- 51.The emergency injection for the treatment of adrenal crisis. Addison’s Disease Self Help Group. Accessed November 2024. https://www.addisonsdisease.org.uk/the-emergency-injection-for-the-treatment-of-adrenal-crisis

- 52.How to give an emergency injection – leaflets for your kit. Addison’s Disease Self Help Group. Accessed November 2024. https://www.addisonsdisease.org.uk/how-to-give-an-emergency-injection-leaflets-for-your-kit

- 53.Preparing your own emergency kit for Addison’s or adrenal insufficiency. Addison’s Disease Self Help Group. Accessed November 2024. https://www.addisonsdisease.org.uk/blog/preparing-your-own-emergency-kit-for-addisons-or-adrenal-insufficiency

- 54.Patient information. British Society of Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes. Accessed November 2024. https://www.bsped.org.uk/clinical-resources/patient-information/

- 55.Adrenal crisis information. Society for Endocrinology. Accessed November 2024. https://www.endocrinology.org/clinical-practice/clinical-guidance/adrenal-crisis

- 56.Shepherd LM, Tahrani AA, Inman C, Arlt W, Carrick-Sen DM. Exploration of knowledge and understanding in patients with primary adrenal insufficiency: a mixed methods study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2017;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12902-017-0196-0

- 57.Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes [NG5]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015. Accessed November 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5

- 58.Picton C, Wright H. Keeping patients safe when they transfer between care providers – getting the medicines right. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2012. Accessed November 2024. https://www.rpharms.com/resources/reports/getting-the-medicines-right