Shutterstock.com

By the end of this article, you should be able to:

- Define attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD);

- Recognise the signs and symptoms of ADHD and its impact on functioning across an individual’s lifespan;

- Know the diagnostic criteria for ADHD.

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by age-inappropriate levels of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity[1,2]. These symptoms lead to an impairment in functioning across multiple settings — such as home, education, employment and the wider community — and have the potential to influence the developmental trajectory of the individual[2].

The prevalence of ADHD varies significantly worldwide owing to the variable diagnostic practices and how rigorously the criterion for impairment is applied[2]. If the ‘Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders’ (DSM) IV classification are applied, the prevalence can range from between 6.8% to 15.8%. The British Child and Mental Health Survey reported a prevalence of 3.6% in male children and less than 1% in female children. The ratio of boys to girls with ADHD is 4:1; however, in adults this is closer to 1:1 and is distributed across all social classes[2].

Up to 87% of children diagnosed with ADHD will have one or more comorbidities, while 67% will have at least two[1]. These can include autism spectrum disorder (ASD), oppositional defiance disorder (ODD), major depression and generalised anxiety disorder (GAD)[1]. Up to 85% of children continue to experience symptoms into adolescence and up to 60% will continue to do so into adulthood[1].

This article is the first in a two-part series and focuses on the diagnosis of ADHD. Information relating to management and support can be found in ‘Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: management and support‘.

Recognition and identification

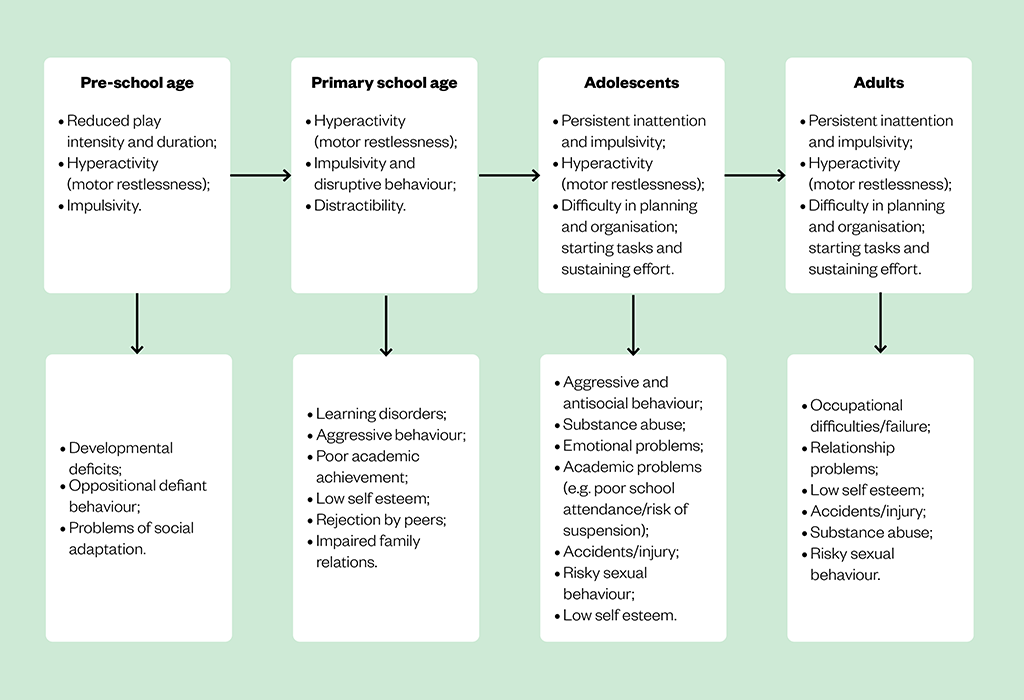

The core symptoms of ADHD are inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity (see Figure 1). These symptoms and the related functional impairments emerge in childhood, usually before the age of 12 years and change across the lifespan[2,3]. Inattention symptoms are more noticeable in adolescence and usually persist through to adulthood[3,4]. Inattention is characterised by a disorganised style and difficulty sustaining focus to complete tasks[2]. Hyperactivity symptoms typically manifest as excessive motor activity. In pre-school children this may present as constant and demanding extremes of activity; in school-aged children it may involve excess movements in situations that require behavioural self-control[2]. In adolescents and adults, these symptoms are less overt and may manifest as excessive fidgeting or an inner sense of restlessness[2,3]. Impulsivity symptoms usually persist throughout life and resemble impatience or taking hasty actions without considering the consequences, culminating in high risk behaviours[2,5].

The aetiology of ADHD is complex and not fully understood. It is thought to involve multiple genetic and environmental factors, which lead to altered brain neurochemistry and structure[2,7] (see Box 1). Mean heritability is estimated at 77% based on twin studies[2,8].

Box 1: Groups with an increased prevalence of ADHD[9]

Groups that have an increased prevalence of ADHD include:

- People born pre-term;

- Looked after children and young people;

- Children and young people diagnosed with oppositional defiance disorder (negative and disruptive behaviour, particularly towards authority figures, such as parents and teachers) or conduct disorder (a tendency towards highly antisocial behaviour, such as stealing, fighting, vandalism and harming people or animals);

- Children and young people diagnosed with mood disorders, such as anxiety and depression;

- People with a close family member diagnosed with ADHD;

- People with epilepsy;

- People with neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder, tic disorders, a learning disability (intellectual disability) and specific learning difficulties;

- People with a mental health condition;

- People with a history of substance misuse;

- People known to the youth justice system or adult criminal justice system;

- People with an acquired brain injury.

Other risk factors associated with ADHD include: low birth weight; maternal smoking or alcohol consumption and exposure to toxins (e.g. lead) during pregnancy; psychosocial adversity (e.g. bereavement, abuse, poverty); and adverse maternal mental health[2,7].

Primary care practitioners play an important role in the early identification and referral of individuals with suspected ADHD[2]. Concerns may originate from parents, teachers or other caregivers[5]. When a child or young person presents with symptoms suggestive of ADHD, practitioners should determine the severity of the problems, how these affect the young person and the family and the extent to which they pervade different domains, (such as the home, school, place of work and local community)[9].

If symptoms are causing an adverse impact on a child or young person’s development or family life, recommendations are to[9]:

- Consider a period of watchful waiting (up to 10 weeks);

- Offer parents or carers a referral to group-based ADHD-focused support (this should be offered immediately and should not wait until after a formal diagnosis).

Persistent problems causing significant impairment lead to a referral to secondary care. Referrals can be made by primary care professionals, education providers, social care, or youth justice professionals. The referrer should inform the individual’s GP. Note that care pathways may vary locally[9].

Adults presenting with ADHD symptoms in primary care or general adult psychiatric services who do not have a childhood diagnosis should be referred for a specialist assessment. The criteria should include evidence that symptoms[9]:

- Began during childhood and have persisted throughout life;

- Are not explained by other psychiatric diagnoses.

Adults previously treated for ADHD as children or young people who continue to have symptoms should be referred to general psychiatric services for assessment. In all cases, the symptoms should be associated with significant functional impairment[9].

Diagnosis

Diagnosing ADHD is a process undertaken by psychiatrists, paediatricians and other trained healthcare professionals who have specialist expertise in its diagnosis and management[9]. It involves careful and comprehensive collation of information about an individual from multiple sources, including parents/carers and children, school teachers, the behaviours observed in each setting, structured observations and a full developmental and psychiatric history[9].

Screening tools — such as the ‘Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire’ (SDQs), Swanson Nolan and Pelham questionnaire (SNAP-IV), and Conner’s questionnaire — are used to supplement the information collated to aid diagnosis but do not replace the process described above[9]. Screening tools are also helpful in monitoring the response to treatment and changes in symptoms[2].

This information is then interpreted against the DSM-5 or ICD-11 criteria for ADHD (see Box 2)[9,10].

Box 2: Criteria for the diagnosis of ADHD as defined by DSM-V[9,10]

A persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development, characterised by (1) and/or (2):

(1) Inattention: Six or more of the following symptoms (≥5 in those aged 17 years or older) have persisted for at least six months to a degree that is inconsistent with the person’s developmental level

- Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work or other activities (e.g. overlooks or misses details, work is inaccurate);

- Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (e.g. difficulty remaining focused during lectures, conversations, lengthy reading);

- Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly (e.g. mind seems elsewhere even in the absence of any obvious distractions);

- Often does not follow through on instructions; fails to finish schoolwork, duties in the workplace or other chores (e.g. starts tasks but quickly loses focus and easily distracted);

- Often has difficulty organising tasks and activities (e.g. difficulty managing sequential tasks; difficulty keeping materials and belongings in order; messy, disorganised work; poor time management; fails to meet deadlines).

- Often avoids, dislikes or is reluctant to do tasks requiring sustained mental effort (e.g. schoolwork/homework; for adolescents and adults — preparing reports, completing forms, reviewing lengthy papers);

- Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g. school materials, keys, wallet, paperwork);

- Is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli; may include unrelated thoughts in adolescents and adults;

- Is often forgetful in daily activities (e.g. doing chores, running errands; for adolescents and adults — keeping appointments, returning calls, paying bills).

(2) Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six or more of the following symptoms (≥5 in those aged years or older) have persisted for at least six months to a degree that is inconsistent with the person’s developmental level

- Often fidgets or taps hands or feet or squirms in seat;

- Often leaves seat in situations where remaining seated is expected (e.g. in the classroom, workplace);

- Younger children often run or climb excessively where inappropriate, or feelings of restlessness in adolescents or adults;

- Difficulty playing or engaging in leisure activities quietly;

- Is often ‘on the go’ or often acts as if ‘driven by a motor’ (e.g. is unable or uncomfortable being still for extended periods of time i.e. in restaurants/meetings; may be experienced by others as being restless or difficult to keep up with);

- Often talks excessively and blurts out answers before questions have been completed, completes people’s sentences;

- Often has difficulty awaiting turn;

- Interruption or intrusion of others (e.g. butts into conversations or games; may use other people’s things without asking or receiving permission; for adolescents and adults, may intrude into or take over what others are doing).

In addition to the above the following must also be present:

- Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present before the age of 12 years;

- Several hyperactive-impulsive or inattentive symptoms are present in two or more settings (e.g. at home, school or work; with friends or relatives; in other activities);

- There is clear evidence of significant impairment in social, academic or occupational functioning;

- Symptoms must not be solely attributable to other mental health disorders, illness or environmental factors.

ADHD can be sub-divided into the following presentations[4]:

- Predominantly inattentive type (~20–30% of cases);

- Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type (~15% of cases);

- A combined presentation of inattention and hyperactivity and/or impulsivity (~50–75% of cases).

Evidence suggests that ADHD in females is underrecognised and underdiagnosed because female children are less likely to exhibit impulsive, hyperactive and disruptive behaviours prompting evaluation and referral[1]. Female children predominantly display symptoms of inattention and may be incorrectly diagnosed with another psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorder potentially resulting in missed diagnosis of ADHD[1,4,9].

Symptoms of ADHD can overlap or even co-exist with other psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, conduct disorder or bipolar disorder[4,11]. It is therefore important to identify and differentiate these comorbidities as they may affect treatment plans[11]. This can be achieved through detailed history taking, mental state examination and collateral information[12].

Patient counselling and support

Living with ADHD is challenging as the symptoms can significantly impair daily functioning. Once a diagnosis is made, the following advice may help improve quality of life for individuals and their support network[7,9,13].

Encourage individuals and their support network to seek guidance and support from training programmes. For parents/carers this may include:

- Positive parent/carer child contact;

- Structure in the child or young person’s day;

- Clear and appropriate rules about behaviour and consistent management;

- Ensure parents/carers are aware that the above advice does not imply bad parenting and the aim is to optimise skills to meet the above average parenting needs;

- Advise individuals (or their parents/carers where appropriate) to discuss additional support/adjustments required with educational facilities/employers;

- Signpost individuals (and their families/carers) to further information and support, such as self-help, local and national support groups and voluntary organisations.

Further resources

- The National Attention Deficit Disorder Information and Support Services (ADISS), which provides information, training and support for parents, patients and professionals in the fields of ADHD and related learning and behavioural difficulties;

- The ADHD Foundation, a neurodiversity charity, offering a strength-based, lifespan service for people who live with conditions such as ADHD, autism, dyslexia, developmental co-ordination disorder, dyscalculia, obsessive compulsive disorder and Tourette’s syndrome;

- Adult Attention Deficit Disorder UK (AADDUK), a charity focused on raising awareness of ADHD in adulthood, advancing the education of professionals and the public at a national and local level in the UK;

- Information from MIND on how to access mental health support for people with ADHD;

- NHS Health A-Z, an accessible overview of ADHD covering symptoms, causes, diagnosis, treatment and living well.

- 1Harpin V, editor. The Management of ADHD in Children and Young People. London: : Mac Keith Press 2017. http://www.mackeith.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Prelims-from-HB-13-Harpin-HAPRIN-ADHD-web.pdf (accessed Apr 2023).

- 2Mirza K, Mirza S, Sudesh R. A guide to ADHD in children and adolescents. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, Supplement. 2017.https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/pb-assets/HMED/Guides/BJHM_Guide_to_ADHD-1515517966040.pdf (accessed Apr 2023).

- 3Volkow ND, Swanson JM. Adult Attention Deficit–Hyperactivity Disorder. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1935–44. doi:10.1056/nejmcp1212625

- 4Halliwell N. Top Tips: ADHD in Children and Young People. Medscape UK. 2021.https://www.medscape.co.uk/viewarticle/top-tips-adhd-children-and-young-people-2022a100106w?uac=304350ET&impID=4712315&sso=true&faf=1&src=mkm_ret_221004_mscpmrk-GB_GIPCA-nofilter (accessed Apr 2023).

- 5Krull K, Chan E. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. 2023.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-in-children-and-adolescents-clinical-features-and-diagnosis#H830607547 (accessed Apr 2023).

- 6Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines. Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance . 2018.https://www.caddra.ca/wp-content/uploads/CADDRA-Guidelines-4th-Edition_-Feb2018.pdf (accessed Apr 2023).

- 7Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2022.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder/ (accessed Apr 2023).

- 8Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Mick E. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis, Lifespan, Comorbidities, and Neurobiology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:631–42. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm005

- 9Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management: NICE guideline NG87. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2018.www.nice.org.uk/ng87 (accessed Apr 2023).

- 10American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). 5th ed. Arlington, VA: : American Psychiatric Association 2013. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm (accessed Apr 2023).

- 11Symptoms of ADHD. ADHD Institute. https://adhd-institute.com/assessment-diagnosis/symptoms-of-adhd/ (accessed Apr 2023).

- 12Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. BMJ Best Practice. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/142 (accessed Apr 2023).

- 13Living with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. NHS. 2021.www.nhs.uk/conditions/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/living-with/ (accessed Apr 2023).