Science Photo Library

After reading this case study you will be able to:

- Identify the symptoms of primary biliary cholangitis and know how the disease is diagnosed;

- Understand the initial treatment options and how treatment response is monitored;

- Understand how suitability for second-line treatment is evaluated.

Treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) aims to slow disease progression and reduce the need for liver transplantation. However, even with treatment, PBC remains a progressive disease with risk of liver-related complications and death[1]. As described in ‘Primary biliary cholangitis: diagnosis and management’, it is also associated with a high symptom burden that can affect a patient’s quality of life (QoL)[2–4].

As the clinical course of PBC is highly variable, it is imperative that treatment is personalised. There is an opportunity for pharmacist involvement in ensuring treatment and supportive therapies are optimised; a multidisciplinary approach should be adopted to maximise patient outcomes.

This case study follows the journey of a patient with PBC after they are referred to a virtual pharmacy-led PBC multidisciplinary team (MDT) at a large tertiary referral centre for consideration for obeticholic acid (OCA) therapy, following non-response to ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA).

Presentation

A female patient, aged 60 years, was diagnosed with PBC after being referred by her GP to specialist hepatology services following the identification of unexplained cholestatic biochemistry on routine blood tests. The patient presented with an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 981 units/L (reference range 30–130 units/L) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) of 482 units/L (reference range 15–40 units/L), with a normal bilirubin level. She had some mild pruritus on referral but was otherwise fit and healthy. She had no history of autoimmune conditions and was on no regular medication.

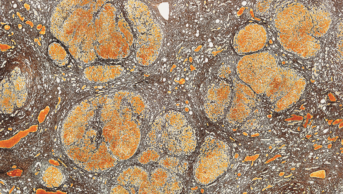

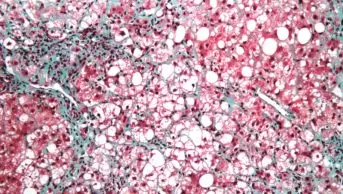

A liver screen was completed that confirmed the presence of anti-mitochondrial (AMA) and anti-nuclear (ANA) autoantibodies, both are specific serological markers of PBC. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) excluded the differential diagnosis and crossover syndrome of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). PSC is characterised by mural irregularities and multifocal strictures causing a ‘beaded’ appearance that is not present in PBC[5,6]. The patient underwent transient elastography (FibroScan) to stage the extent of liver disease and was found to have mild fibrosis.

The patient was started on UDCA at a dose of 15mg/kg/day — this is the first-line treatment recommended by international guidelines — and colestyramine 4g twice daily for pruritus[1,2,7,8].

Reviewing response to treatment

At 12 months of treatment, the patient should undergo a repeat ALP test to determine their response to treatment. As the ALP result was 440units/L, which is over 1.67x upper limit of normal (ULN), she was deemed to be an UDCA non-responder. Non-response to UDCA is defined as ALP>1.67xULN and/or bilirubin>ULN (but less than 2xULN) after one year of treatment[1,2,7,9].

First-line treatment failure

The patient should be referred to a specialist centre with a designated PBC MDT; in this case they were referred to the virtual pharmacy-led PBC MDT at a tertiary referral centre for consideration. A standardised referral form was emailed to the hepatology pharmacist who presented the case to the PBC MDT, which consists of two hepatologists and two hepatology pharmacists. It was decided that the patient was a suitable candidate for OCA as she did not respond to first-line treatment and had no history of hepatic decompensation, biliary obstruction or signs of portal hypertension (e.g. ascites, oesophageal varices, persistent thrombocytopenia). The patient was counselled regarding the introduction of OCA and was consented for homecare by the hepatology pharmacist. The patient was started on a dose of 5mg once daily, to be continued alongside UDCA at the same dose of 15mg/kg/day. The patient was counselled to look out for any signs of worsening liver function, such as jaundice or ascites, and were informed that they may experience worsening of their pruritus. They were advised to contact the hepatology pharmacist should this happen.

Pruritus

The patient was advised to reduce OCA to 5mg three times a week, and a plan for managing their pruritus was communicated to their hepatologist. In line with British Society of Gastroenterology recommendations, the patient was started on rifampicin 150mg twice daily, to be taken at least one hour before colestyramine, and menthol 1% in aqueous cream to be applied as required[2,8]. The patient was advised to store the cream in the fridge to enhance the cooling effect. The benefits of non-pharmacological options, such as the avoidance of tight-fitting clothes and hot showers, were also reiterated. The patient was informed to increase their OCA dose to 5mg once daily when their pruritus was under control.

Follow-up

The patient was contacted by the hepatology pharmacist one month later to assess tolerability and efficacy of rifampicin, and the patient reported her pruritus was much improved. She had therefore increased her dose of OCA to 5mg once daily and reported tolerating this dose well with the additional antipruritic agents.

At six months, repeat bloods were requested from the spoke site that showed an ALP of 313units/L. The patient was telephoned to assess tolerability – they reported no worsening of pruritus and were happy to increase to 10mg once daily as per licensing[10]. At 12 months, ALP had fallen to 197units/L, less than 1.67xULN. Bilirubin remained normal.

Long-term management

The patient continues on OCA 10mg daily and will have bloods checked every six months to ensure a response to treatment is sustained. They continue taking rifampicin, colestyramine and menthol 1% in aqueous cream, which appears to be managing their pruritus well. It was expected that a higher dose of OCA would result in worsening pruritus in this patient, however, the earlier optimisation of anti-pruritic agents appears to have alleviated this risk.

The PBC OCA International Study of Efficacy (POISE) trial demonstrated that OCA is effective in reducing ALP by 12 months but is associated with adverse effects such as new-onset or worsening pruritus, as seen in this patient. The trial showed that pruritus was dose dependent[6]. As demonstrated by this case, a temporary reduction in dose and optimisation of anti-pruritic agents can increase tolerability of OCA.

Summary

This case highlights how good symptom management, and regular follow up with the patient can improve tolerability and adherence to OCA and result in good clinical outcomes.

This case also highlights the role of hub-and-spoke sites in managing patients who do not respond to first-line treatment with UDCA, and how pharmacy can lead the provision of this service within tertiary referral centres.

- 1Hirschfield GM, Beuers U, Corpechot C, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Journal of Hepatology 2017;67:145–72. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.022

- 2Hirschfield GM, Dyson JK, Alexander GJM, et al. The British Society of Gastroenterology/UK-PBC primary biliary cholangitis treatment and management guidelines. Gut 2018;67:1568–94. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315259

- 3PBC Symptoms. PBCers Organization. 2019.https://pbcers.org/symptoms/ (accessed Sep 2021).

- 4Primary Biliary Cholangitis. American Liver Foundation. 2017.https://liverfoundation.org/for-patients/about-the-liver/diseases-of-the-liver/primary-biliary-cholangitis (accessed Sep 2021).

- 5Mago S, Wu GY. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis and Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Overlap Syndrome: A Review. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology 2020;8:1–11. doi:10.14218/jcth.2020.00036

- 6Sirpal S, Chandok N. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: diagnostic and management challenges. CEG 2017;Volume 10:265–73. doi:10.2147/ceg.s105872

- 7Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, et al. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology Published Online First: 6 November 2018. doi:10.1002/hep.30145

- 8Pate J, Gutierrez JA, Frenette CT, et al. Practical strategies for pruritus management in the obeticholic acid-treated patient with PBC: proceedings from the 2018 expert panel. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2019;6:e000256. doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2018-000256

- 9Nevens F, Andreone P, Mazzella G, et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Obeticholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:631–43. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1509840

- 10Intercept Pharma UK and Ireland. Summary of Product Characteristics: OCALIVA 10mg film-coated tablets. Medicines.org . 2018.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7630/smpc (accessed Sep 2021).