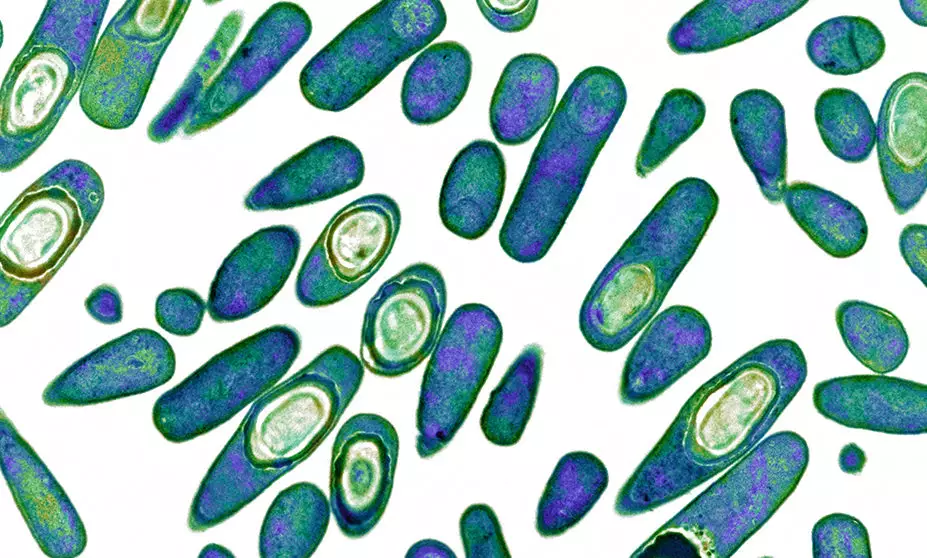

BIOMEDICAL IMAGING UNIT, SOUTHAMPTON GENERAL HOSPITAL/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Understand the evidence base for the use of oral vancomycin and fidaxomicin in Clostridioides difficile infection;

- Understand the rationale for the use of novel therapies;

- Advise on appropriate supportive or non-pharmacological measures;

- Advise on drug administration involving patients with swallowing difficulties or enteral tubes.

Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) is a spore-producing Gram-positive anaerobic bacterium and a leading cause of healthcare-associated infection. C. difficile is a commensal organism within the human intestinal flora found in up to 66% of newborn babies; colonisation rates drop over time and around 3% of healthy adults remain colonised[1]. Most colonised patients remain asymptomatic; however, disturbances of the enteric microbiome — typically following antibacterial therapy — can cause C. difficile to proliferate and induce toxin production resulting in local inflammation and C. difficile infection (CDI).

CDI is characterised by inflammation of the large intestine, or colon, which manifests as diarrhoea, abdominal pain and distension. Complications include life-threatening toxic megacolon (an acute and severe dilatation of the colon) and pseudomembranous colitis (an acute and severe inflammation of the colon). Diagnosis is confirmed with the presence of symptomatic diarrhoea (≥3 stools/24hours) and either microbiological confirmation of C. difficile organism in a stool sample, radiological evidence of pseudomembranous colitis or histopathological characteristics of CDI[2].

Cases of toxin-confirmed CDI in England have fallen from 55,498 in 2007/2008 to 13,177 in 2019/2020, owing to improvements in infection, prevention and control (IPC), antibacterial prescribing practice and the introduction of antimicrobial stewardship services[3,4]. However, despite improvement, CDI is still associated with significant patient harm with 30-day all-cause mortality high at 13.5% post CDI diagnosis[5]. Early diagnosis, avoidance of CDI triggers (e.g. antibacterials) and prompt targeted treatment is essential for improving patient outcomes.

The Public Health England guidance on CDI diagnosis and management, last updated in 2013, has now been superseded by the recent publication of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)[6,7]. This article summarises the important updates related to the management of CDI and the implications for pharmacy practice across primary and secondary care[7]. As the diagnosis and classifications of CDI severity remain unchanged from the PHE advice, please refer to ‘Clostridium difficile: diagnosis and treatment update’ for further information[6,8].

Pharmacological management

Vancomycin

The oral glycopeptide vancomycin remains an important therapeutic option for the management of CDI infection. It is well tolerated and achieves therapeutic concentrations within the lumen of intestines. Owing to cost, it has traditionally been limited to severe infections where it has been used in preference to metronidazole with superior outcomes (overall clinical cure 97% vs. 84%, P=0.006, respectively)[9]. Severe infections are associated with a white cell count >15×109/L, or an acutely increased serum creatinine concentration (greater than 50% increase above baseline), or a temperature higher than 38.5°C, or evidence of severe colitis (abdominal or radiological signs)[6,9]. The number of stools may be a less reliable indicator of severity. For non-severe CDI, metronidazole was associated with non-inferior outcomes (90% vs. 98%) (P=0.36) and has been previously recommended for use[6].

More recent analysis demonstrates superiority of vancomycin over metronidazole for CDI in both severe and non-severe infection[10]. A recent Cochrane review has confirmed this initial analysis and has seen vancomycin replace metronidazole as treatment of choice for CDI, irrespective of initial severity (relative risk [RR]: 0.9; 95% CI: 0.84−0.97)[11]. NICE’s health economic analysis presents vancomycin as the most cost-effective treatment for CDI, replacing metronidazole as treatment of choice for non-severe CDI episodes, and is in line with other international guidance[7,12,13].

Combination therapy of oral vancomycin with intravenous metronidazole is thought to increase luminal penetration of antibacterials in CDI and is recommended by NICE for treatment-resistant or severe/life-threatening CDI[14]. However, this may not translate into successful patient outcomes and further evidence is needed[7,15].

Administration and monitoring

Vancomycin must be administered enterally; little to no faecal concentration is obtained by parenterally administered vancomycin. A licensed oral capsule (125mg and 250mg) and a vial of injectable powder (which may be reconstituted and administered enterally) are currently available, with the latter advised for patients with swallowing difficulties or enteral tubes[7]. Unlicensed liquid preparations may be sourced in community settings if patients and/or carers experience difficulty when reconstituting a vial.

The rectal route of administration may be utilised in addition to the oral route, or as an alternative route, in patients with severe/life-threatening disease or if ileus present[7]. Rectal or intra-colonic administration of vancomycin is unlicensed in the UK but may be prepared by reconstituting one 500mg vial in 100ml of normal saline, which is subsequently given as a retention enema four times a day[12]. Caution is advised in any manipulation of an injectable powder for enteral or rectal administration owing to the risk of accidental parenteral administration. Confusion regarding route may occur when an oral solution is prepared using syringes and needles for parenteral use[16].

Oral vancomycin has minimal systemic absorption hence the risk of systemic adverse effects associated with glycopeptide antibacterials (such as ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity) is negligible[7]. Therapeutic drug monitoring is not routinely advised at the standard dosage of 125mg four times a day for ten days[17]. In patients with high-dose oral vancomycin therapy (500mg four times a day) and end-stage kidney dysfunction, random serum vancomycin levels may be useful to exclude any potential accumulation but this is not universally recommended[18].

The standard oral vancomycin dose of 125mg four times a day is recommended by NICE as previous data showed no statistically significant difference in symptomatic cure between standard and high dosing regimens[7,11]. Tapered or pulsed dosing regimens, thought to target spores of C.difficile (which are resistant to antibiotics), allowing time for spores to germinate into vegetative forms that can be subsequently treated upon dose administration are not currently recommend by NICE[7,19].

It is thought that increased use of oral vancomycin can create a selective pressure and increase the incidence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE); however, the risk remains unconfirmed in practice[20].

Fidaxomicin

The macrocyclic antibacterial fidaxomicin exhibits bacteriocidal activity against C. difficile and is recommended as second-line therapy for CDI (of any severity) as an alternative to vancomycin[7,21]. In previous national guidance, it was reserved for patients with recurrent CDI infections and was only to be used following local microbiology recommendations[6].

Two large prospective randomised control trials have helped demonstrate the efficacy of fidaxomicin for treatment of CDI. Initial work by Louie et al., randomised 629 patients to receive oral fidaxomicin (200mg twice daily) or vancomycin (125mg four times daily) for ten days[22]. Clinical cure of active CDI with fidaxomicin was non-inferior to that of vancomycin[22]. Rates of reoccurrence, indicated by diarrhoea and positive stool toxin test within four weeks post-treatment, was significantly lower in patients treated with fidaxomicin with around a number needed to treat of ten to prevent one reoccurrence[22]. Cornely et al. confirmed this finding with similar clinical cure achieved with both fidaxomicin and vancomycin[23]. Again, a reduction in recurrence rates of CDI was evident with the fidaxomicin treatment group[23]. Based on the favourable reoccurrence rates, fidaxomicin appears to be an appropriate treatment option for patients at higher risk of disease reoccurrence (e.g. those with previous reported relapses/reoccurrence and those requiring continuing concomitant broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy despite new CDI disease)[7].

The EXTEND study explored the use of tapered fidaxomicin therapy (200mg twice daily for five days then 200mg every 48 hours) and demonstrated low rates of disease reoccurrence with this tapered course[24]. However, no direct head-to-head studies have examined this with the licensed fidaxomicin dosing regimen. NICE currently states that there is insufficient evidence of benefit to recommend this approach[7].

Administration and monitoring

Fidaxomicin is generally well tolerated and has negligible systemic absorption. Rates of adverse effects are similar between fidaxomicin and oral vancomycin[22]. A licensed 200mg tablet is currently available on the NHS with a new 40mg/mL granule oral suspension expected soon to market, allowing for more convenient dose administration for those with swallowing difficulties[25]. Limited information is available related to crushing of the film-coated tablet but there are cases where this has been done to facilitate safe administration[26].

Faecal microbiota transplant

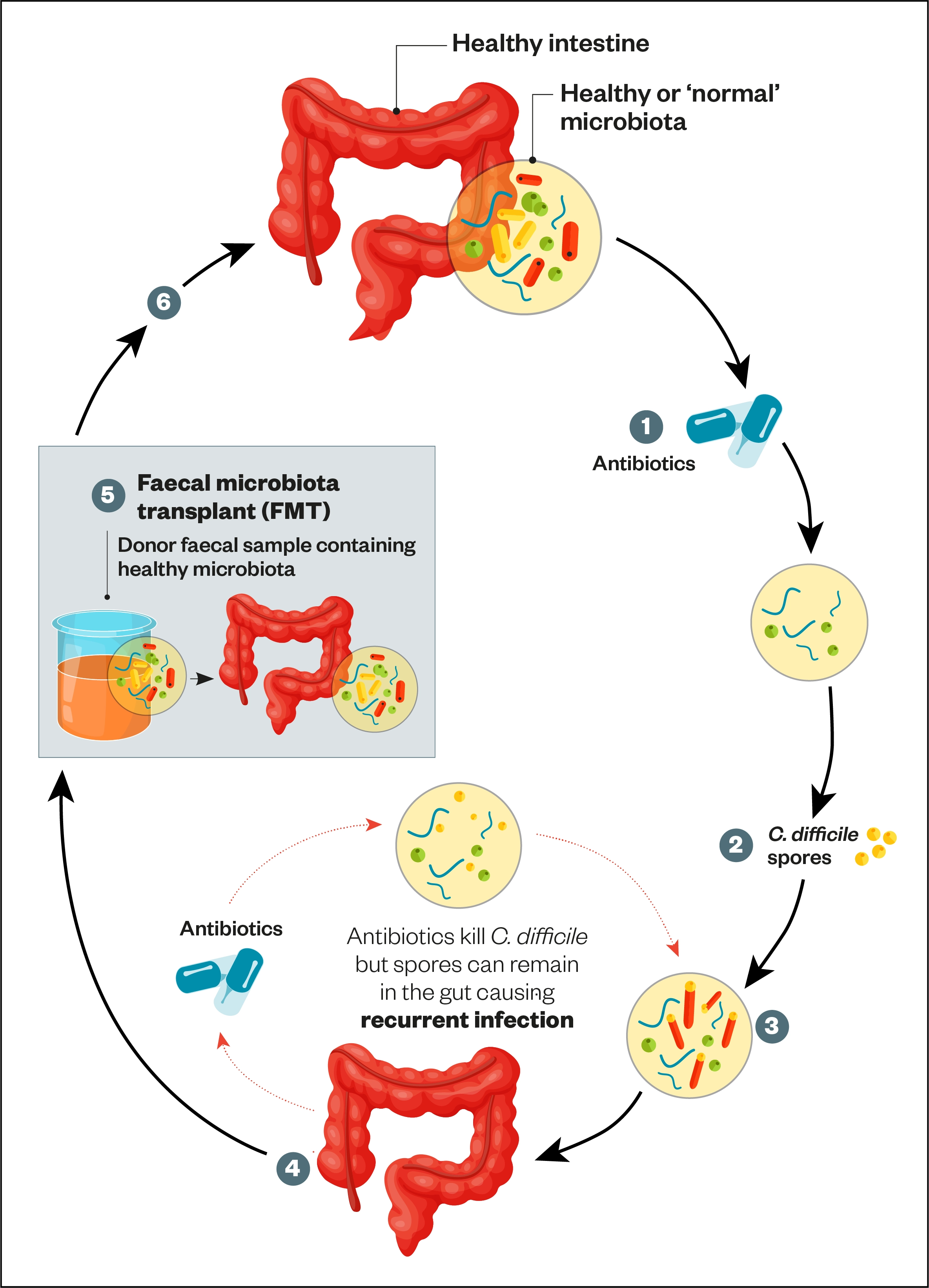

NICE approved the use of faecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in 2014 for recurrent or refractory CDI[27]. The procedure involves the transfer of enteric bacteria from donor faeces to a patient with active infection to help re-establish a healthy balance of bacteria. Donor faecal matter is formulated into frozen aliquots of suspension, which is subsequently administered orally via capsules or nasogastric tube or rectally via colonoscopy (see Figure)[27].

1) Ingesting antibiotics results in a reduction of microbial species and diversity;

2) Spores picked up from the environment are ingested;

3) The C. difficile spores germinate resulting in dysbiosis of the gut microbiota;

4) This can result in the development ofC. difficile infection (characterised by severe diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea and fever). Inflammation and cell death occurs due to presence of toxins. Severe C. difficile infection can cause pseudomembranous colitis;

5) Faecal microbiota transplant: the faecal sample is filtered and administered by enema, transcolonic infusion or nasoduodenal infusion;

6) The result is restoration of stable, healthy microbiota.

Source [8]

FMT was more efficacious at achieving clinical cure of recurrent CDI unresponsive to antibacterials rather than refractory CDI infections[28,29]. A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis found that both single and repeated FMT procedures were superior then oral vancomycin alone at treating recurrent CDI[30]. Consequently, in hospital settings, FMT is used as a third-line option in recurrent CDI patients who have had repeated antibacterial therapy. NICE recommends FMT in patients who have previously had two or more episodes of CDI that were unresponsive to antibiotics[7,27].

Patients may experience mild gastrointestinal effects such as nausea, diarrhoea and bloating post-FMT. NICE acknowledges that FMT carries a small risk of transmitting multi-drug resistant bacteria (in particular Escherichia coli) from the donor to the patient but this is minimised by donor screening and sample testing prior to use[7].

Bezlotoxumab

The human monoclonal antitoxin antibody bezlotoxumab is licensed for the prevention of recurrent CDI in adults and has been shown to reduce recurrence by up to 12 weeks[31,32]. However, it is no longer recommended owing to a lack of cost-effectiveness[7].

Supportive and non-pharmacological management

Alongside evidence-based pharmacological treatment options for the management of CDI, pharmacists should consider the following supportive and non-pharmacological options:

- Stop or review use of broad-spectrum antibacterials

Broad-spectrum antibacterials (e.g. co-amoxiclav, clindamycin and ciprofloxacin) disturb enteric flora and can cause proliferation of C. difficile[6,7]. All antibacterial prescribing should be limited to the shortest effective duration and rationalised in line with available microbiological data.

- Stop or review use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

PPI agents such as omeprazole support the acquisition and proliferation of C. difficile in the intestine by reducing the acidic nature of gastric contents[6,7]. The need for a PPI should be reviewed in patients at-risk of or confirmed CDI, with unnecessary PPI use stopped where possible to reduce risk of future CDI disease.

- Avoid using antimotility agents

Using an agent such as loperamide in a patient with CDI risks the C.difficile toxin being retained in the intestine and subsequent development of toxic megacolon disease[6,7].

- Avoid prebiotics and probiotic supplements in patients taking antibacterials

There is a lack of convincing evidence for these supplements to be routinely prescribed for prevention of CDI[7].

- Ensure patients are appropriately hydrated

Patients should be encouraged to drink fluids or use oral rehydration sachets to avoid dehydration associated with severe diarrhoea.

- Provide infection prevention and control advice

Patients with CDI should be encouraged to practice good hand hygiene regularly and wash down contaminated surfaces. Patients should stay at home until at least 48 hours after their most recent episode of diarrhoea.

Impact on pharmacy practice

Updated guidance on management will significantly impact the practice of pharmacy teams within community and hospital settings in a variety of ways (see Box), including the potential number of prescriptions seen in practice. Clinical commissioning groups are advised to review local guidelines for the clinical management and antibacterial prescribing in CDI that considers the increased cost of fidaxomicin and the implication on local prescribing budgets.

Box: Impact of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance on C. difficile management on pharmacy teams

Prescribing practice issues

Pharmacists should:

- Challenge oral metronidazole prescriptions for CDI and encourage the use of oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin as described by NICE[7]. For more information on how to review the choice of an antimicrobial, see ‘How to evaluate the clinical appropriateness of an antimicrobial’;

- Review any concomitant PPIs and broad-spectrum antibacterials;

- Be aware that antibacterial prophylaxis for C. difficile is not recommended.

Stock, procurement and cost issues

Community pharmacists should:

Consider holding or increasing stock levels of oral vancomycin and fidaxomicin. The cost of fidaxomicin is significantly greater than vancomycin and local prescribing budgets must account for this, but fidaxomicin is funded by NHS England when used in line with local CDI guidelines.

Patient counselling and outcomes issues

Pharmacists should:

- Counsel patients on the indication, dose, frequency, duration and side effects of their CDI therapy;

- Inform patients to contact their prescriber if side effects are experienced within a few days of starting therapy or if there is no improvement in symptoms within one week;

- Counsel patients on self-care and infection prevention and control measures to minimise transmission to others.

- 1Clostridioides difficile: guidance, data and analysis. Public Health England. 2019.https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/clostridium-difficile-guidance-data-and-analysis (accessed Oct 2021).

- 2Clostridium difficile: updated guidance on diagnosis and reporting. Department of Health and Social Care. 2012.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/updated-guidance-on-the-diagnosis-and-reporting-of-clostridium-difficile (accessed Oct 2021).

- 3Annual epidemiological commentary; Gram negative bacteraemia, MRSA bacteraemia, MSSA bacteraemia and C.difficile infections up to and including financial year April 2019 to March 2020. Public Health England. 2021.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1016843/Annual_epidemiology_commentary_April_2020_March_2021.pdf (accessed Oct 2021).

- 4Gerding DN, Muto CA, Owens, Jr. RC. Measures to Control and PreventClostridium difficileInfection. CLIN INFECT DIS 2008;46:S43–9. doi:10.1086/521861

- 5Thirty-day all-cause mortality following MRSA, MSSA and Gram-negative bacteraemia and C.difficile infections. Public Health England. 2021.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/951922/hcai_fatality_report_201920.pdf (accessed Oct 2021).

- 6Updated guidance on the management and treatment of Clostridium difficile infections. Public Health England. 2013.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/clostridium-difficile-infection-guidance-on-management-and-treatment (accessed Oct 2021).

- 7Clostridioides difficile infection: antimicrobial prescribing. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ conditions-and-diseases/infections/healthcareassociated-infections/products ?GuidanceProgramme=guidelines (accessed Oct 2021).

- 8Geoghegan O, Eades C, Moore L, et al. Clostridium difficile: diagnosis and treatment update. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2017.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/clostridium-difficile-diagnosis-and-treatment-update (accessed Oct 2021).

- 9Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KMLST, et al. A Comparison of Vancomycin and Metronidazole for the Treatment of Clostridium difficile-Associated Diarrhea, Stratified by Disease Severity. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007;45:302–7. doi:10.1086/519265

- 10Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, et al. Vancomycin, Metronidazole, or Tolevamer for Clostridium difficile Infection: Results From Two Multinational, Randomized, Controlled Trials. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2014;59:345–54. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu313

- 11Nelson RL, Suda KJ, Evans CT. Antibiotic treatment for Clostridium difficile -associated diarrhoea in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017;2017. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004610.pub5

- 12McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018;66:e1–48. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1085

- 13Nana T, Moore C, Boyles T, et al. South African Society of Clinical Microbiology Clostridioides difficile infection diagnosis, management and infection prevention and control guideline. Southern African Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020;35. doi:10.4102/sajid.v35i1.219

- 14Rokas KEE, Johnson JW, Beardsley JR, et al. The Addition of Intravenous Metronidazole to Oral Vancomycin is Associated With Improved Mortality in Critically Ill Patients WithClostridium difficileInfection. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:934–41. doi:10.1093/cid/civ409

- 15Wang Y, Schluger A, Li J, et al. Dose addition of intravenous metronidazole to oral vancomycin improve outcomes in Clostridioides difficile infection? Clinical Infectious Diseases Published Online First: 12 November 2019. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz1115

- 16Root T. Choosing between oral vancomycin options. Specialist Pharmacy Services. 2021.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/choosing-between-oral-vancomycin-options/ (accessed Oct 2021).

- 17Vancomycin. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/vancomycin.html (accessed Oct 2021).

- 18Cimolai N. Does oral vancomycin use necessitate therapeutic drug monitoring? Infection 2019;48:173–82. doi:10.1007/s15010-019-01374-7

- 19Singh T, Bedi P, Bumrah K, et al. Updates in Treatment of Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection. J Clin Med Res 2019;11:465–71. doi:10.14740/jocmr3854

- 20Stevens VW, Khader K, Echevarria K, et al. Use of Oral Vancomycin for Clostridioides difficile Infection and the Risk of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019;71:645–51. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz871

- 21Venugopal AA, Johnson S. Fidaxomicin: A Novel Macrocyclic Antibiotic Approved for Treatment of Clostridium difficile Infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2011;54:568–74. doi:10.1093/cid/cir830

- 22Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, et al. Fidaxomicin versus Vancomycin forClostridium difficileInfection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:422–31. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0910812

- 23Cornely OA, Miller MA, Louie TJ, et al. Treatment of First Recurrence of Clostridium difficile Infection: Fidaxomicin Versus Vancomycin. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2012;55:S154–61. doi:10.1093/cid/cis462

- 24Guery B, Menichetti F, Anttila V-J, et al. Extended-pulsed fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection in patients 60 years and older (EXTEND): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3b/4 trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2018;18:296–307. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(17)30751-x

- 25Fidaxomicin. Specialist Pharmacy Service. 2016.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/medicines/fidaxomicin/ (accessed Oct 2021).

- 26Smeltzer S, Hassoun A. Successful use of fidaxomicin in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in a child. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2013;68:1688–9. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt079

- 27Faecal microbiota transplant for recurrent or refractory Clostridioides difficile infection MIB 247. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib247 (accessed Oct 2021).

- 28Tariq R, Pardi DS, Bartlett MG, et al. Low Cure Rates in Controlled Trials of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for RecurrentClostridium difficileInfection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018;68:1351–8. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy721

- 29Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Gasbarrini A, et al. A network meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials exploring the role of fecal microbiota transplantation in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. United European Gastroenterol j 2019;7:1051–63. doi:10.1177/2050640619854587

- 30Baunwall SMD, Lee MM, Eriksen MK, et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2020;29–30:100642. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100642

- 31ZINPLAVA 25 mg/mL concentrate for solution for infusion. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/ emc/product/2669/smpc (accessed Oct 2021).

- 32Wilcox MH, Gerding DN, Poxton IR, et al. Bezlotoxumab for Prevention of RecurrentClostridium difficileInfection. N Engl J Med 2017;376:305–17. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1602615

You might also be interested in…

Norovirus and strategies for infection control

Case-based learning: insect bites and stings