Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Define risk communication;

- Describe why developing effective risk communication skills is important for pharmacists;

- Use the information in this article to develop your own risk communication skills;

- Develop strategies to communicate risk to patients to support and empower shared decision making in relation to their health and wellbeing.

Post-registration foundation pharmacist curriculum

This article will support the development of knowledge and skills related to the following Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) credentialling areas:

Post-registration foundation pharmacist curriculum

1.1 Communicates effectively with people receiving care and colleagues;

1.3 Consults with people through open conversation; explores physical, psychological and social aspects for that person, remaining open to what a person might share; empowers the person creating an environment to support shared decision making around personal healthcare outcomes and changes to health behaviour;

2.1 Applies evidence based clinical knowledge and up to date guidance to make suitable recommendations or take appropriate actions with confidence;

2.5 Manages uncertainty and risk appropriately.

Core advanced pharmacist curriculum

1.1 Communicates complex, sensitive and/or contentious information effectively with people receiving care and senior decision makers.

Introduction

Medical practice relies on the careful balancing of risks and benefits. Proposed treatments or investigations, as well as their alternatives, need to be considered and pharmacists use data in conversations with patients and carers to ensure they are aware of these risks and that their consent to proceed is fully informed. By doing so, pharmacists can build better relationships and trust with patients.

Discussion of risk and data with patients is a nuanced process with multiple considerations. In preventative medicines and treatment of long-term conditions, it can require a personalised approach to assessment of risk. Pharmacists will consider patient factors, such as risk tolerance and impact on quality of life. In polypharmacy and deprescribing activities, pharmacists will consider cumulative risks and prioritisation of risk versus benefit profiles, with the overall safety profile of a high medicine burden. The commonality is shared decision making and continual review in order to achieve effective patient care.

The General Pharmaceutical Council’s (GPhC) standards for pharmacy professionals describe how safe and effective care must be delivered1. The standard applicable to discussion of risk and health data with patients is standard 3: ‘pharmacy professionals must communicate effectively’1. However, pharmacists might not always consider how they communicate information or data when discussing risks associated with clinical conditions, their associated treatments or investigations. It is important to consider how this communication can affect patient outcomes.

Pharmacists are essential in meeting the ambitions of ‘The NHS long-term plan’ for disease prevention and optimising outcomes from medicines2. The expansion of prescribing within the profession, and the associated assumption of new roles and responsibilities for pharmacists, makes the consolidation of this essential skill especially important.

Why risk communication is important

Traditionally, healthcare professionals were often trusted by patients and their carers to make decisions on their behalf. Healthcare professionals may have used their professional judgement in determining the amount of information to disclose in relation to a treatment or intervention. However, this practice is inappropriate and outdated — the GPhC is clear in its guidance on consent, which states that patients have a basic right to be involved in decisions about their care3.

Pharmacists should ensure that individuals are supported to make appropriate decisions for themselves. This is an important part of the healthcare professional consultation process and is what is known as ‘shared decision making’. Discussion of risk is an important component of this; it enables decisions to be aligned with personal values and perspectives and founded upon a true understanding of the relative benefits rather than misapprehension4.

Pharmacists must be aware of, and practice according to, regulatory standards, the law and good practice guidance relating to consent3. Additionally, they should understand relevant case law that might influence discussion of risk and potential consequences for the patient and their professional practice.

In achieving this, it is important to revisit what is meant by ‘the Bolam test’ in determining medical professional negligence. This was devised on the 1957 ruling of ‘Bolam versus Friern Hospital Management Committee’5 and is used to determine whether the actions of a medical professional (pharmacists included) are in line with the actions of others in their position, or in accordance with a responsible body of professional opinion and the evidence base in that area.

If their respective judgements are found to be so aligned, the Bolam test is considered to have been passed and there is no case for negligence; however, the judgement in the case of ‘Montgomery vs. Lanarkshire Health Board’ in 2015 changed the legal landscape6. The case brought fresh light on what constitutes informed consent7.

Box 1 outlines the facts in relation to this case.

Box 1: Facts relating to ‘Montgomery versus Lanarkshire Health Board’

The key passages from the Montgomery judgment involve what a patient would consider to be material risk:

“The test of materiality is whether, in the circumstances of the particular case, a reasonable person in the patient’s position would be likely to attach significance to the risk, or the doctor [or healthcare professional] is or should reasonably be aware that the patient would be likely to attach significance to it.8”

The case demanded review of informed consent after a woman with small stature, diabetes and large baby in utero experienced complications owing to shoulder dystocia on delivering her baby vaginally.

Her baby suffered hypoxic brain injury and consequent cerebral palsy. The obstetrician had not disclosed the increased risk of complications with vaginal delivery for this woman, given her history.

The woman stated she would have requested a caesarean section had she been informed of the increased risks of vaginal delivery, and the court accepted this. The woman subsequently sued for negligence and the Supreme Court ruled in her favour. The ruling determined that ‘the Bolam test’ was not applicable in this case and the doctor should have disclosed sufficient information regarding risk of vaginal delivery and considered the consequences of this risk from the patient’s perspective.

In the case of Montgomery vs. Lanarkshire Health Board, it was determined that ‘the Bolam test’ was not applicable on disclosure of risk to patients. It was established that patients should be told what they want to know and not only what the medical professional considers to be important. The court determined that patients should be given sufficient information regarding risks and that healthcare professionals should also consider the risks from the patient’s perspective8.

The court was clear that risk discussion does not require overwhelming patients with information about every conceivable risk; however, material risk should be considered. Applying a test of materiality requires you to ask: “Would a reasonable person in the patient’s position be likely to attach significance to this risk?6” Discussion of material risk encourages a more patient-centred and holistic approach to care, which should be the modern context of healthcare practice9.

The ways in which we can do this clearly and effectively will be discussed later in this article, but Box 2 includes some reflective questions that can help identify relevant considerations of risk applied to individual patients.

Box 2: Reflective questions to use when consideration risk and informed consent

Each patient consultation will be unique but the following questions taken from ‘Medical Ethics Today: the BMA’s Handbook of Ethics and Law’, can be used to guide your approach when seeking consent from a patient8:

- Is the patient aware of any risks that are relevant to the decision about the treatment?

- Is the patient aware of any suitable alternatives and the risks and benefits of those?

- Have I taken reasonable measures to ensure I have presented this information clearly and in a way my patient can understand it?

Why it is important to use data effectively in conversations with patients

A patient’s feelings about or understanding of the data could change their understanding of the information and mean they cannot make an objective decision10. Risk perception varies enormously between patients and patient groups. Perception of risk can be deeply affected by the method of communication and individuals’ own internal risk scoring scale.

Patients may have their own preconceptions or perceptions about the weight of risk, influenced by personal, emotional or societal factors. For example, when explaining the risk of acute pancreatitis associated with GLP1-RA therapy for diabetes, the side effect of acute pancreatitis should be discussed.

This risk might be acceptable to ‘Patient X’, who may not fully understand what acute pancreatitis is or may be willing to try anything to avoid insulin treatment owing to severe diabetes complications. But ‘Patient Y’ might refuse treatment without further discussion because a relative of theirs was hospitalised with acute pancreatitis linked to GLP 1-RA use.

Another confounding factor is the patient’s level of health literacy and/or numeracy11. The pharmacist might think that they have provided a balanced overview of risks and benefits during a consultation; however, health information is often inadvertently presented using complex terminology, assumed knowledge, jargon and numbers that have not been put into context. In the UK, 16.4% of adults (1 in 6) have ‘very poor literacy’ skills, reading at or below the age of a 9-year-old12,13. Evidence also shows that 4 in 10 adults in the UK struggle to understand health content written for the public, while 6 in 10 adults struggle to understand health information that contains numbers and statistics13. Pharmacists should keep these facts in mind when considering how to use data in conversations with patients.

How to discuss risks and data with patients

All diseases, treatments and interventions confer some element of risk. There are some strategies that pharmacists can employ when using data in conversations with patients and communicating risk to make this process more effective.

To discuss risks and data with patients, it is important to first consider8:

- The nature of the risk;

- The effect the risk would have on the life of the patient;

- How important the benefits of a treatment or intervention are to the patient;

- The available alternatives and risks associated with these.

Use a simple decision-making tool, such as ‘BRAN’ (benefits, risks, alternatives, nothing), in consultations to prompt patients to engage in shared decision making14,15 (see Table15).

Factors that affect the patient’s perception of information

Framing effect

The ‘framing effect’ is a concept that pharmacists need to be aware of when discussing data and risk with patients. ‘Framing’ a risk or benefit using relative instead of absolute terms has been found to significantly influence patient perception16,17.

A patient is being informed about a particular treatment option and the risk of adverse outcomes. There are two ways the risk can be framed:

- It reduces the chance of an adverse outcome from 10% to 5% — a relative risk reduction of 50%;

- It has a 5% chance of an adverse outcome — an absolute risk of 5%.

Patients are much more likely to choose a treatment when it is framed using the relative risk reduction. Changes in risk appear larger this way than when presented in terms of absolute risk18.

Recency effect and primacy effect

Patients’ perception of risk can also be influenced by the order in which the data are presented. The ‘recency effect’ is a cognitive bias in which those items, ideas or arguments that came last are remembered more clearly than those that came first. Presenting risks or harms after the benefits of treatments can increase worry and reduce acceptance of treatment16,19.

Conversely, presenting risks or harms prior to benefits of treatments can affect the patient’s ability to take in the rest of the information discussed, this is another example of cognitive bias known as the primacy effect.

Number needed to treat

‘Number needed to treat’ (NNT) is a statistical concept that measures the effectiveness of an intervention. It tends to be used predominantly in epidemiology and public health when populations are being considered. It can also be a useful tool to help patients understand the benefits of their medicines. This can also be compared with the ‘number needed to harm’ when discussing associate risk of adverse events. NNT can be particularly helpful when discussing long-term medicines or prophylactics.

NNT is a concept that some patients may find hard to understand, so it should not be the only way data are presented to patients18,20. It can also contribute to the framing effect and may influence how the patient views their medicines (and subsequent adherence).

Percentage and frequency

There is some evidence that patients prefer information to be presented as percentages or frequencies18. Be aware of how your presentation of the data may affect the perception of risk.

Consider this example: the risk of side effect X is 5%. Would this mean more to the patient if that is presented as 50 in 1,000 people will experience side effect X? What about if it is presented as 5 in 100 people? The risk is 5% in both cases, but the risk in the second version could appear greater to the patient. The principal factor when communicating frequencies is to use a small and consistent denominator4,10.

Probabilities

Discussing probabilities is challenging and often difficult to achieve using verbal methods. Using terms such as ‘likely’ or ‘uncommon’ can lead to subjective, inaccurate interpretations10. It is also important to consider adding clarity around ‘possibility’ and ‘probability’. Risk predicts both, but it can be useful to communicate the difference when discussing data with patients.

Consider this example4: you have calculated a Q-RISK3 score of 7.9%. Is it possible that the patient will develop cardiovascular disease in the next ten years? Yes. Is it probable? No.

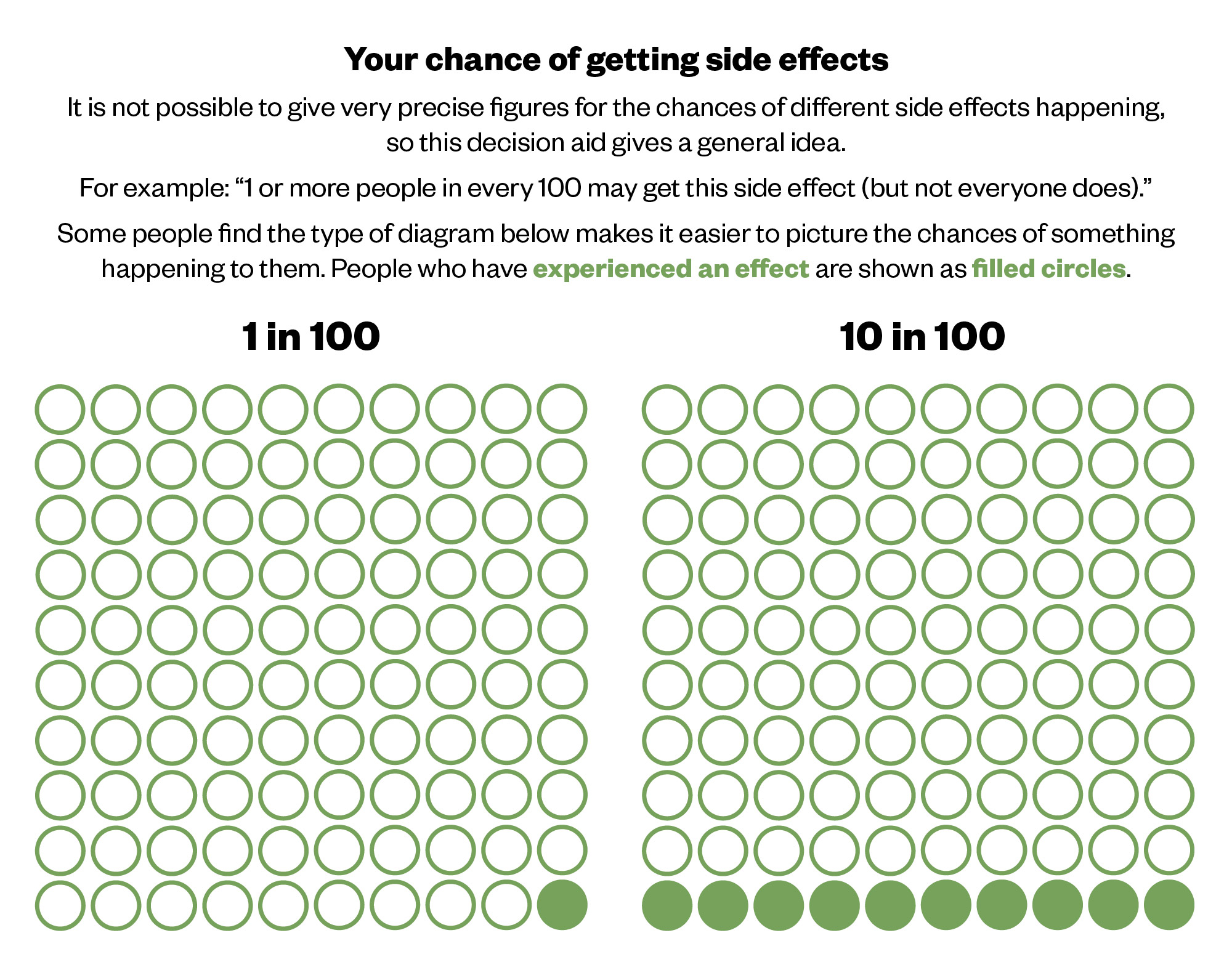

Visual aids

Visual and graphical formats are useful for helping patients understand data. Pie charts, bar graphs and simple pictographs are all excellent methods for communicating outcomes to patients4. The challenge lies in choosing the most appropriate one for your discussion. Pictographs are more useful for representing frequency than probability, showing those affected and not affected (both the numerator and the denominator) (see Figure 1)18,21.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) patient decision aids commonly use pictographs and it is likely that this is what pharmacists will have available when discussing risk with patients22. Reassuringly, accurate risk perceptions and knowledge are improved when these types of decision aids are used when preparing for or during the consultation22.

The Pharmaceutical Journal, based on NICE patient decision aids

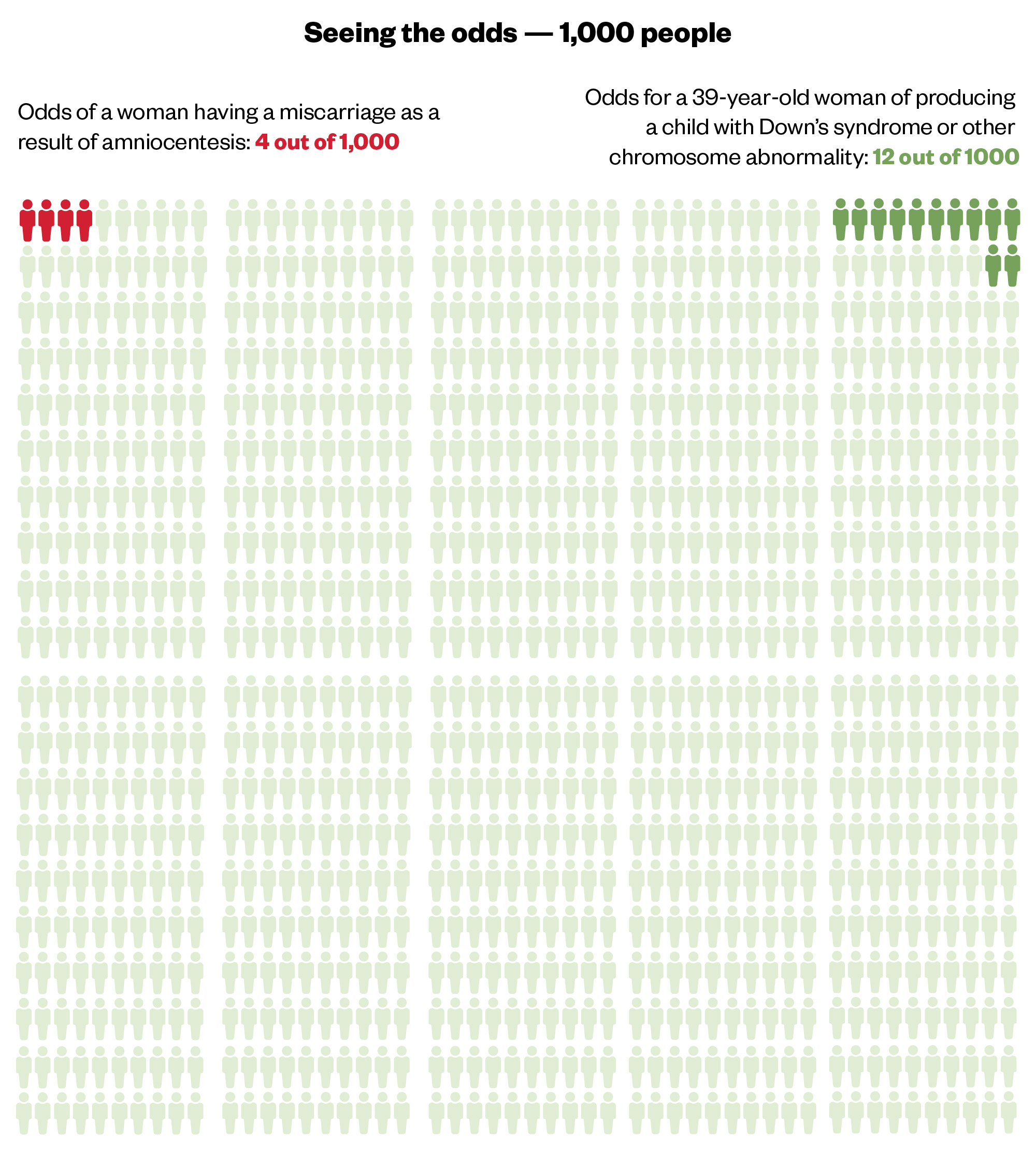

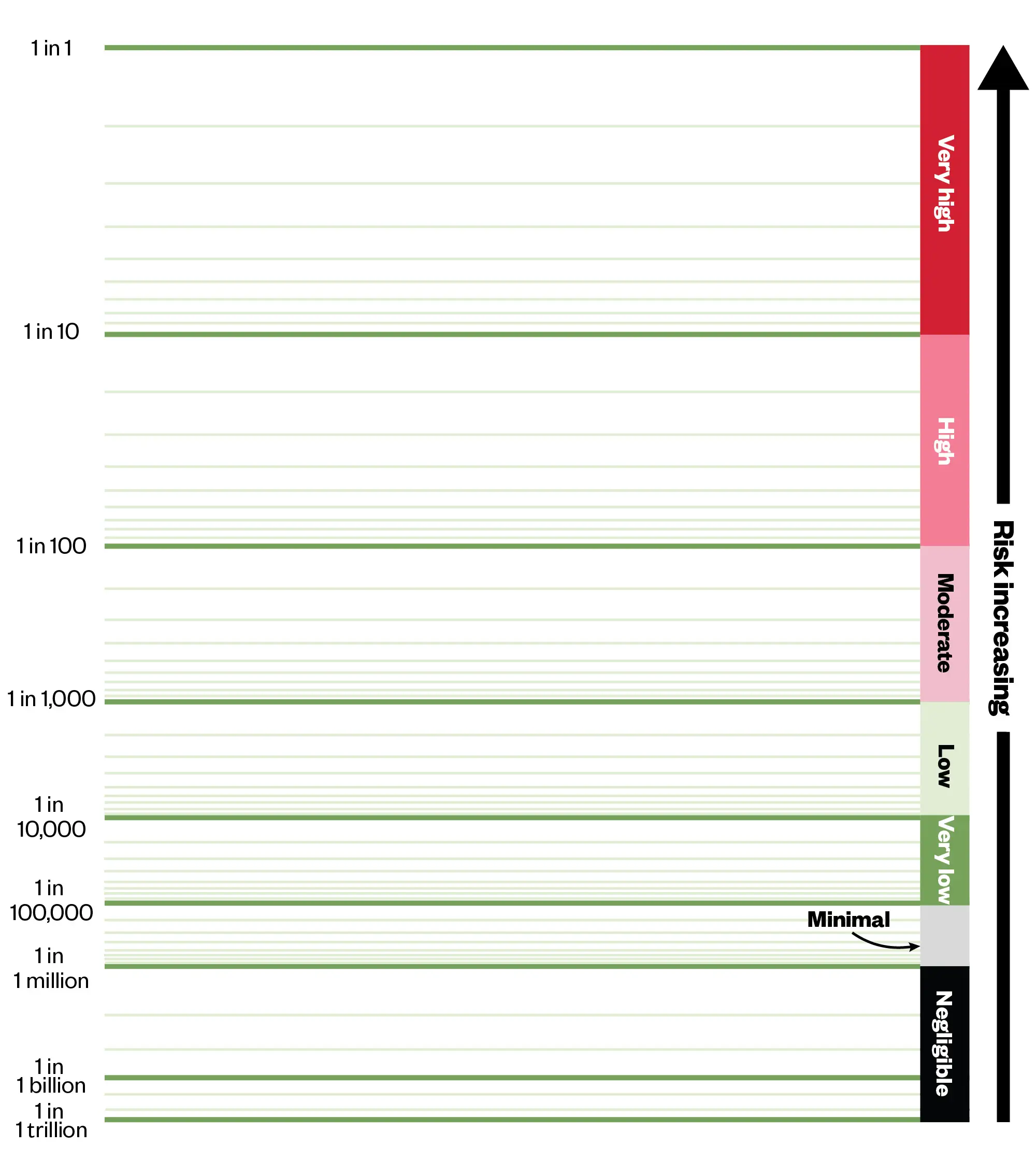

Other simple visual communication tools include the Paling Palette, to depict frequency of events occurring (see Figure 2) and the Paling Perspective Scale, to display magnitude of risk (see Figure 3). These have been shown to increase patient partnership in decision-making processes10.

The Pharmaceutical Journal, based on the Risk Communication Institute

The Pharmaceutical Journal, based on the Risk Communication Institute

A combination of word and numeric descriptors have been found to increase understanding of risk23. Pharmacists should routinely be using effective combinations of methods in their communication and consultations with patients.

Exceptions for communicating risk with patients

There are a few scenarios in which communication of risk might not be appropriate. The most commonly encountered is in emergency situation, in which the patient may lack capacity to consent to a treatment or intervention, but it is deemed to be in the best interest of the patient to prevent deterioration in a condition or save their life3.

Other scenarios that may be encountered are more controversial and professional guidance for pharmacists is lacking. For instance, a patient may state that they categorically do not want to know about risks from treatment. This is entirely different to a patient’s right to refuse a treatment or intervention after being informed. It is referred to as the ‘right not to know’. However, there is no guidance on this topic for pharmacists and there is ongoing debate in the medical field around the ethics and guidance for healthcare professionals when a patient claims the right not to be informed of risks. Given the ethical uncertainty and possible need for an amount of minimum information a patient may need in this scenario, legal advice should be sought.

There is one more scenario in which communication of risk might be inappropriate. If you believe that giving certain information to a patient could lead to serious harm — not just becoming upset, refusing treatment or wanting to choose an alternative — you can choose not to give it. However, it has been made clear by the Supreme Court that this exception must not be abused8. This scenario is likely to be extremely rare and possibly compounded by other issues such as mental capacity. In any case, legal advice and clear documentation is paramount.

Box 3: Five tips for using data in conversations with patients

- Be conscious of framing and recency biases in your communication;

- Use small and consistent denominators when discussion frequencies;

- Discuss risk in terms of absolute risk;

- Use visual tools, such as pictographs and Paling Palettes10;

- Use a combination of word and numeric descriptors.

Conclusion

By equipping pharmacists with the necessary knowledge, tools and strategies to enhance patient understanding and empowerment, the quality of patient care can be improved and patient engagement with their medicines and overall health can be increased. Improving the way data are communicated may go some way toward tackling health inequalities, by ensuring that patients can make informed health decisions using information they have understood.

As medicines experts, pharmacists can play a vital role communicating risk and data to improve adherence to treatment and optimise health outcomes. As the pharmacist role expands to include a higher degree of clinical practice and prescribing, we are now more heavily involved in the investigation of clinical conditions and will be accountable for our role in the shared decision-making process. Pharmacists must take responsibility for communicating risk as a fundamental part of safe and effective patient consultation.

- 1.Standards for Pharmacy Professionals. General Pharmaceutical Council . Published 2017. Accessed July 2024. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/pharmacists/standards-and-guidance-pharmacy-professionals/standards-pharmacy-professionals

- 2.The NHS Long-Term Plan. NHS. Published 2019. Accessed July 2024. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/

- 3.In practice: Guidance on consent. General Pharmaceutical Council . Published June 2018. Accessed July 2024. https://assets.pharmacyregulation.org/files/2024-01/in_practice_guidance_on_consent_june_2018.pdf

- 4.Schrager S. Five Ways to Communicate Risks So That Patients Understand. Fam Pract Manag. 2018;25(6):28-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30422613

- 5.Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee. Law Teacher. Published 1957. Accessed July 2024. https://www.lawteacher.net/cases/bolam-v-friern-hospital-management.php

- 6.Mongomery vs. Lanarkshire Health Board . Law Teacher. Published 2015. Accessed July 2024. https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/docs/uksc-2013-0136-judgment.pdf

- 7.Chan SW, Tulloch E, Cooper ES, Smith A, Wojcik W, Norman JE. Montgomery and informed consent: where are we now? BMJ. Published online May 12, 2017:j2224. doi:10.1136/bmj.j2224

- 8.Medical Ethics Today: Consent, choice and refusal: adults with capacity. British Medical Association. Published 2017. Accessed July 2024. https://www.bma.org.uk/media/1988/bma-met-chapter-2-update-may-2017.pdf

- 9.Lee A. ‘Bolam’ to ‘Montgomery’ is result of evolutionary change of medical practice towards ‘patient-centred care.’ Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2016;93(1095):46-50. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134236

- 10.Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327(7417):745-748. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7417.745

- 11.Numeracy and managing your health. National Numeracy. Published 2018. Accessed July 2024. https://www.nationalnumeracy.org.uk/research-and-resources/numeracy-and-managing-your-health

- 12.Adult Literacy. National Literacy Trust. Published 2024. Accessed July 2024. https://literacytrust.org.uk/parents-and-families/adult-literacy/

- 13.Health Information: Are You Getting Your Message Across? National Institute for Health Research; 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_51109

- 14.How to use a decision support tool. NHS England. Accessed July 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/shared-decision-making/decision-support-tools/how-to-use-a-decision-support-tool

- 15.Choosing Wisely. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Accessed July 2024. https://www.aomrc.org.uk/projects-and-programmes/choosing-wisely

- 16.Malenka DJ, Baron JA, Johansen S, Wahrenberger JW, Ross JM. The framing effect of relative and absolute risk. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(10):543-548. doi:10.1007/bf02599636

- 17.Gordon-Lubitz RJ. Risk Communication: Problems of Presentation and Understanding. JAMA. 2003;289(1):95. doi:10.1001/jama.289.1.95

- 18.Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Helping Patients Decide: Ten Steps to Better Risk Communication. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011;103(19):1436-1443. doi:10.1093/jnci/djr318

- 19.Zipkin DA, Umscheid CA, Keating NL, et al. Evidence-Based Risk Communication. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(4):270. doi:10.7326/m14-0295

- 20.Akl EA, Oxman AD, Herrin J, et al. Using alternative statistical formats for presenting risks and risk reductions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online March 16, 2011. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006776.pub2

- 21.Patient decision aid CG181: Should I take a statin? National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Accessed July 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng238/resources/patient-decision-aid-on-should-i-take-a-statin-pdf-243780159

- 22.Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017;2017(4). doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001431.pub5

- 23.Sawant R, Sansgiry S. Communicating risk of medication side-effects: role of communication format on risk perception. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2018;16(2):1174. doi:10.18549/pharmpract.2018.02.1174