Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Discuss the changes in the pharmacist role from medicines focused to clinically focused;

- Describe the learning needs of newly qualified pharmacists to enable the development of complex decision-making skills;

- Identify ways in which pharmacists can support newly qualified pharmacists to develop complex decision-making skills.

The delivery of healthcare is a complex activity. It is an ongoing process that requires clinicians to respond to changing scenarios and identify how the available scientific evidence relates to an individual situation[1]. Pharmacy has moved from being a medicines-focused dispensing service to a clinical service, so pharmacists need to be proficient in clinical decision-making[2].

Clinical decision-making requires clinicians to gather high-quality information, consider context and draw on existing knowledge and experience[3]. There is often no single right answer, meaning that pharmacists need to feel comfortable dealing with uncertainty, operating in grey areas and taking an approach that maximises the chance of a good outcome. Patients and the wider NHS require pharmacists who can progress from novice (able to manage simple decisions) to expert (characterised by highly developed clinical reasoning skills). This transition requires them to develop the way that they assess risks, benefits and consequences, often in fast moving environments and with incomplete information.

The General Pharmaceutical Council’s ‘Standards for the initial education and training (IET) of pharmacists’ require pharmacists to “play a much greater role in providing clinical care to patients and the public from their first day on the register”[4]. The IET standards emphasise professional judgement, management of risk, diagnostic and consultation skills and, significantly, enable pharmacists to independently prescribe from the point of registration[5]. They also require foundation pharmacists to be able to engage people in shared decision-making, a person-centred intervention described by the NHS as a ‘universal’ way to support people to gain more choice and control over their health and care needs[5,6].

Embedding shared decision-making into practice requires pharmacists to understand both their own approach to decision-making, and also that of their patients. This is a change that will require a shift in culture and engagement from everyone involved in patient care[7].

Demand for health and care is expected to increase in the period to 2030/2031 and the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing health inequalities within society and has put services under greater pressure[8,9].

The pandemic also showed how increased complexity can put teams under greater strain. David Gibson associate dean, early career pharmacists, school of pharmacy and medicines optimisation (North), Health Education England, and lead clinical pharmacist at County Durham and Darlington Foundation Trust, helped develop and deliver the Interim Foundation Pharmacist Programme to support provisionally-registered pharmacists as they entered the workforce[10]. He also identified the need for increased support to develop complex decision-making abilities and shared his reflections for this article (see Box).

Box: Applying complex decision-making skills

David Gibson explains how he applied complex decision-making skills in his response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Many healthcare professionals found the first few weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic disorienting. The usual certainties of clinical practice were absent. For me, this came to a head one morning when I was asked to help convert hospital operating theatres into COVID-19 wards. The situational awareness I had developed over 20 years as a pharmacist had been disrupted by the new scenario. I felt a disorientation that made decision-making more challenging. I am now aware that many healthcare practitioners have described a deep fatigue associated with the pandemic. I believe this can be partly explained by the fact that deliberative thinking, which the new situations and challenges raised by the pandemic has required, takes more cognitive effort.

“This experience prompted the collaboration between Health Education England (HEE) and the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors to develop a suite of resources to help pharmacists with decision-making — ‘Coping with complexity’[3]. These resources were initially focused on supporting provisionally-registered pharmacists through the HEE interim foundation pharmacist programme[10]. They enable early-career pharmacists to acquire practical skills in decision-making, become familiar with the context in which these skills are to be employed, and develop the confidence to make effective decisions in practice.”

To evaluate this new ‘Coping with complexity’ resource, Health Education England commissioned a report on it as a resource for pharmacists enrolled on the Interim Foundation Pharmacist Programme[3,11]. After reviewing interviews with ten educational supervisors who were supporting learners on the pathway, the report found that the learning needs for foundation pharmacists were:

- To acquire practical skills in decision-making;

- To become familiar with the context in which these skills are to be employed;

- To develop the confidence to make effective decisions in practice.

Skill acquisition

The way we make decisions is complex and influenced by many factors. Decision-making is a well-established area of psychology and, over time, it has been possible to develop a large number of strategies, tools and approaches that provide an opportunity to structure your decisions and, with practice, improve the likelihood of achieving a successful outcome.

Within healthcare, one such method of developing decision-making skills is through the creation of illness ‘scripts’. The use of scripts originates in computer science as structures that help to frame common stories or events[12]. Within healthcare, illness scripts are focused on the identification and management of disease and, in this way, they can help to identify the benefit of considering the script for a wide range of pharmacists’ professional activities. The scripts act as mental cue cards that record and structure the professional’s knowledge of a particular illness or disease.

Undergraduate, foundation and newly qualified pharmacists have acquired theoretical knowledge of these scripts for different diseases and clinical scenarios. Exposure to practical, real-world scenarios then help to develop the script over time[13,14]. Initially, novice clinicians may take time testing hypotheses against their existing knowledge, but expert clinicians (using highly developed scripts) are able to make fast decisions about patient care by intuitively using data to draw hypotheses[15].

This change over time can be explained by dual-process theory. According to this theory, there are two ways of thinking — fast, non-analytical and effortless (system one thinking), and slow, analytical and effortful (system two thinking)[16]. The novice pharmacist may spend much of their time facing unfamiliar scenarios and using system two thinking, whereas those more experienced will have been exposed to more situations and will be skilled at pattern recognition and using system one thinking.

Context

The ‘Recognition primed decision’ model of rapid decision-making considers context for decision making[17]. This model describes how cues that fall into patterns can be recognised and guide a course of action. This model may not seem as helpful for newly qualified pharmacists, who have limited prior experience. However, it enables those with more experience to codify or describe rules for how they would respond to a given situation, which could be used as a valuable tool for those with less experience[3]. It has been suggested that pharmacists could develop clinical reasoning through observing more experienced colleagues, although there is limited evidence on how this process occurs[18].

Building confidence making decisions

As novice clinical decision-makers, newly qualified pharmacists will approach decision-making in a different way to their more experienced colleagues and will require support as they develop their practice[15,19]. At a time when they need this support the most, newly qualified pharmacists face a transition from tutor-supported learning to independent practice, which can lead them to feel isolated and uncertain about their decision-making ability[20]. There are several methods that have been shown to benefit novice practitioners, including modelling, supervision, mentoring and coaching.

Modelling, the process of articulating one’s thoughts out loud to make reasoning explicit, has been identified as an important way to support the development of clinical reasoning[21]. An emphasis on supervision has been brought into the IET standards with the introduction of the designated prescribing practitioner and designated supervisor roles, therefore increasing the opportunity for modelling to take place[5,22].

A review of the evidence for nursing and medicine found that personal, social and job-related experience can affect the learning and performance of novice practitioners[23]. Some healthcare skills and competencies can only be developed through practice, and supervisors, mentors and senior colleagues can help to highlight development areas and formulate action plans[24]. To normalise this process, line managers and mentors should offer reassurance that development continues into qualified practice and highlight the importance of ongoing learning[24].

Coaching, an approach where a peer or more experienced colleague uses questioning techniques while offering guidance, can offer novices the support that they need. An interesting example of coach-led intervention for novice community pharmacists involved, alongside other interventions, the coach establishing a peer support network through a closed social media group using the WhatsApp messaging platform. The creation of the group offered access to an experienced pharmacist and was found to improve confidence and critical reasoning[25].

Using pharmacy curricula to support continuous development

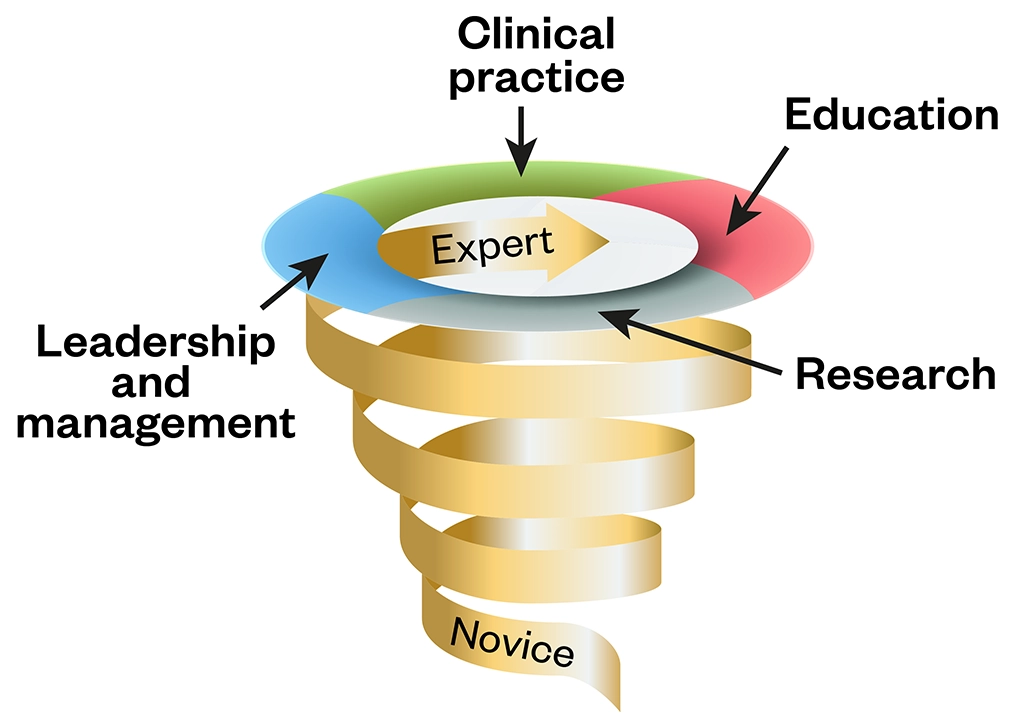

A spiral approach to developing clinical skills may be of benefit: one in which learning draws on past content and builds in difficulty over time[26]. This approach can be bolstered with reflective practice, particularly when supported by feedback from a mentor[27].

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s post-registration foundation pharmacist curriculum, core advanced curriculum, and consultant pharmacist curriculum all map to the four pillars of advanced practice[28–31]:

- Clinical practice;

- Leadership and management;

- Education;

- Research.

The figure below shows how these pillars can be used as tools to support a spiral approach to development. Importantly, the pharmacist curricula all describe the benefits of receiving support from supervisors and mentors (post-registration foundation) and coaches and peers (consultant), and the importance of acting as a mentor to those in the earlier stages[28,30].

Embracing the role of mentor, whether formally as a supervisor or informally as a coach, will help novices to continuously grow and refine their decision-making skills as they transition into the workforce and on to advanced practice.

The changes to the way in which pharmacists are educated are spearheaded by the IET reform, but they will also require everyone in pharmacy practice — from newly qualified through to consultant — to consider their role as educators, mentors and expert decision-makers. As the changes ripple through the profession, it is important that pharmacists become more comfortable with their own decision-making processes, the ways to refine them, and how to articulate them and share their expertise with the next generation.

- 1Benner P, Hughes R, Sutphen M, et al. nursehb. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Published Online First: 1 April 2008.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21328745

- 2Wright DFB, Anakin MG, Duffull SB. Clinical decision-making: An essential skill for 21st century pharmacy practice. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2019;15:600–6. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.08.001

- 3Coping with Complexity. Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors. 2020.https://ergonomics.org.uk/resource/coping-with-complexity.html (accessed Oct 2022).

- 4New standards for initial education and training of pharmacists approved. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2020.https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/news/new-standards-initial-education-and-training-pharmacists-approved (accessed Oct 2022).

- 5Standards for the initial education and training of pharmacists. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2021.www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/standards-for-the-initial-education-and-training-of-pharmacists-january-2021.pdf (accessed Oct 2022).

- 6Comprehensive Personalised Care Model. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/comprehensive-model-of-personalised-care.pdf (accessed Oct 2022).

- 7Shared Responsibility for Health: The Cultural Change We Need. The King’s Fund. The King’s Fund. 2018.https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/shared-responsibility-health (accessed Oct 2022).

- 8Rocks S, Boccarini G, Charlesworth A. Health and Social Care Funding Projections . The Health Foundation. 2021.www.health.org.uk/publications/health-and-social-care-funding-projections-2021 (accessed Oct 2022).

- 9Implementing phase 3 of the NHS response to the COVID-19 pandemic. NHS England. 2020.https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/implementing-phase-3-of-the-nhs-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (accessed Oct 2022).

- 10Interim Foundation Pharmacist Programme. Health Education England. www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/pharmacy/national-training-offers-pharmacy-professionals/interim-foundation-pharmacist-programme (accessed Oct 2022).

- 11Phipps D, Seston E. Complexity and Decision-Making Evaluation. Health Education England 2021.

- 12Schank R. An Early Work in Cognitive Science. In: Scripts, plans, goals and understanding: an inquiry into human knowledge structures. New Jersey: : Hillsdale 1989. 38.http://garfield.library.upenn.edu/classics1989/A1989AN57700001.pdf

- 13Charlin B, Boshuizen HPA, Custers EJ, et al. Scripts and clinical reasoning. Medical Education. 2007;41:1178–84. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02924.x

- 14Keemink Y, Custers EJFM, van Dijk S, et al. Illness script development in pre-clinical education through case-based clinical reasoning training. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:35–41. doi:10.5116/ijme.5a5b.24a9

- 15Norman GR, Brooks LR, Colle CL, et al. The Benefit of Diagnostic Hypotheses in Clinical Reasoning: Experimental Study of an Instructional Intervention for Forward and Backward Reasoning. Cognition and Instruction. 1999;17:433–48. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci1704_3

- 16Hughes M, Nimmo G. Models of Clinical Reasoning. In: ABC of Clinical Reasoning . John Wiley & Sons 2016. https://www.wiley.com/en-gb/ABC+of+Clinical+Reasoning-p-9781119059080 (accessed Oct 2022).

- 17Klein G. A recognition-primed decision (RPD) model of rapid decision making. In: Decision Making in Action: Models and Methods . Ablex 1993. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-recognition-primed-decision-(RPD)-model-of-rapid-Klein/0672092ecc507fb41d81e82d2986cf86c4bff14f (accessed Oct 2022).

- 18Tietze KJ. Clinical reasoning model for pharmacy students. Clin Teach. 2018;16:253–7. doi:10.1111/tct.12944

- 19ten C, Durning S, ten C, et al. spr9783319648286. Published Online First: 7 November 2017. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64828-6_3

- 20Magola E, Willis SC, Schafheutle EI. Community pharmacists at transition to independent practice: Isolated, unsupported, and stressed. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26:849–59. doi:10.1111/hsc.12596

- 21Sylvia LM. A lesson in clinical reasoning for the pharmacy preceptor. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2019;76:944–51. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxz083

- 22Initial Education and Training of Pharmacists – Reform Programme. Health Education England. 2022.www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/pharmacy/initial-education-training-pharmacists-reform-programme (accessed Oct 2022).

- 23Magola E, Willis SC, Schafheutle EI. What can community pharmacy learn from the experiences of transition to practice for novice doctors and nurses? A narrative review. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2017;26:4–15. doi:10.1111/ijpp.12349

- 24Opoku EN, Khuabi L-AJ-N, Van Niekerk L. Exploring the factors that affect the transition from student to health professional: an Integrative review. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02978-0

- 25Magola E, Willis SC, Schafheutle EI. The development, feasibility and acceptability of a coach-led intervention to ease novice community pharmacists’ transition to practice. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2022;18:2468–77. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.03.013

- 26Cooper N, De Silva A, Powell S. Teaching Clinical Reasoning. In: ABC of Clinical Reasoning. John Wiley & Sons 2016. https://www.wiley.com/en-gb/ABC+of+Clinical+Reasoning-p-9781119059080 (accessed Oct 2022).

- 27Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Medical Teacher. 2009;31:685–95. doi:10.1080/01421590903050374

- 28Post-Registration Foundation Pharmacist Curriculum. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2022.www.rpharms.com/development/credentialing/post-registration-foundation/post-registration-foundation-curriculum (accessed Oct 2022).

- 29Core Advanced Curriculum. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2022.https://www.rpharms.com/development/credentialing/core-advanced-pharmacist-curriculum (accessed Oct 2022).

- 30Consultant Pharmacist Credentialing Process. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2022.www.rpharms.com/development/credentialing/consultant/consultant-pharmacist-credentialing (accessed Oct 2022).

- 31Multi-Professional framework for advanced clinical practice in England. Health Education England. 2017.www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/multi-professionalframeworkforadvancedclinicalpracticeinengland.pdf (accessed Oct 2022).