ZEPHYR / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Define epilepsy and be aware of different seizure types;

- Understand what causes the condition and the associated risks;

- Understand how the condition is diagnosed and the main differential diagnoses.

Epilepsy is the most common serious neurological condition in the UK, affecting around 600,000 people[1]. Pharmacy teams in primary and secondary care are therefore likely to encounter people with epilepsy on a regular basis. Owing to the strong focus on pharmacological management in epilepsy, pharmacists in primary and secondary care can actively support this patient group and should be familiar with the signs and symptoms of epilepsy.

Epilepsy is characterised by the occurrence of seizures. A seizure occurs when there is a sudden burst of abnormal, excessive, synchronous electrical activity in the brain. Epilepsy is not the underlying cause of all seizures; they can be provoked in any individual by anoxia, hypoglycaemia or cardiac pathologies, as well as other causes. Epilepsy is defined as the tendency to have recurrent seizures and is primarily diagnosed after a person has experienced two unprovoked seizures more than 24 hours apart (see Box 1)[2]. The pattern and severity of seizures experienced can vary considerably between individuals and the unpredictable nature of seizures is one of the main complications reported by people diagnosed with the condition[3].

Box 1: Practical definition of epilepsy based on the International League Against Epilepsy task force

Epilepsy is a disease of the brain defined by any of the following conditions:

- At least two unprovoked (or reflex [i.e. induced by a specific trigger]) seizures occurring >24 hours apart;

- One unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures, similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next ten years, based on neurologist experience;

- Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome[2].

Epilepsy is defined as resolved in individuals with an age-dependent epilepsy syndrome, who are now past the age criteria for certain syndromes, or those who are seizure-free for more than ten years, with no antiseizure medicines (ASMs) and have not needed antiseizure medicines for the past five years.

Epidemiology

Epilepsy is caused by an underlying problem within the brain and is therefore often associated with comorbidities. For example, central nervous system-related conditions, such as depression, anxiety, sleep issues, migraine and memory problems, occur more frequently in people with epilepsy[4]. There is a higher incidence of somatic conditions, including type 1 diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, arthritis and gastric bleeds, suggesting that epilepsy is a symptom complex rather than a disease[5–9]. The overall incidence of epilepsy is slightly higher in males than females, with a median incidence of 50.7 compared with 46.2 per 100,000 people [10].

There is a higher prevalence of epilepsy in low-income countries and in deprived areas of higher income countries where patients may be unable to access a specialist, diagnosis may be delayed, or a full range of treatments is not available[11]. In some countries, stigma around epilepsy can mean the condition is hidden[12].

Premature mortality in people with epilepsy is higher than in the general population[13]. In higher income countries, such as the UK, the standardised mortality ratio is 1.6–3.0 but can be as high as 1.3–7.2 in low-to-middle income countries[11]. A leading cause of death is sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), defined as a sudden, unexpected death in a person with epilepsy, with or without evidence for a seizure preceding the death, in which there is no evidence of other disease, injury, or drowning that caused the death — more detail can be found below[14]. SUDEP is estimated to have an incidence rate of 1.16 cases per 1,000 people with epilepsy [15–17].

Suicide is up to 3.5–5.8 times greater among people with epilepsy, compared with the general population[16]. Premature mortality from other comorbidities, including pneumonia, cancers and ischaemic heart disease, is also higher than in age-matched patients at various stages of the life course, even in those who are seizure free for many years[18].

Aetiology and risk factors

While epilepsy can arise at any age, it has a bimodal distribution indicative of the most common causes[19]. There is an incidence peak in infancy, often caused by brain damage during birth; there is a high association between epilepsy and intellectual disabilities and developmental disorders[20]. There is a second peak in older age owing to cerebrovascular disease, with seizures common after stroke[21]. The incidence steadily increases after age 50 years, with the greatest increase seen in those aged over 80 years. In recent years, the number of people experiencing epilepsy in older age has exceeded young people as maternal health care has improved and life expectancy has increased[19].

Less common causes of epilepsy include brain tumours, head injury and/or central nervous system infections, such as meningitis[22]. In developing countries, infections caused by parasites are the most common cause. For many people worldwide — perhaps as many as 50% — however, the cause of their epilepsy is not determined[23].

It is possible that many epilepsies have an underlying genetic cause, although this may not necessarily be inherited but caused by spontaneous gene mutation. It is not uncommon for someone with epilepsy to have a relative with the condition[24,25]. It is possible that there is a shared genetic basis with comorbidities that arise frequently alongside seizures; for example, depression and psychosis, explaining their strong association with epilepsy and that the risk of these conditions remains high even if seizures are controlled[18,26]. As our understanding of epilepsy increases, it is likely that the role of genetics in epilepsy aetiology will become clearer[24,27].

Seizure types

There are two main classifications of seizure type: focal seizures, which are experienced by around 70% of people with epilepsy, and generalised seizures[24].

In focal seizures (previously called partial seizures) the abnormal electrical activity begins in a localised area, the ‘focus’[24]. The nature of the seizure the person experiences will be dictated by where in the brain that focus is and how far from the focus the seizure activity propagates.

The propagation factor is reflected in the further classification of focal seizures that is subdivided depending on the spread of the seizure activity[2]. If a person experiences a focal aware seizure, consciousness is retained and they will be able to talk during their seizure, respond to instructions and will remember the seizure afterwards. In this case, the seizure activity stays localised to the focus, involving functionally relevant areas that give rise to the manifestation of the seizure.

If the focus is in the temporal lobes, then the person may experience an intense unpleasant sensation, such as smelling a strong smell or feeling an overwhelming sense of déjà -vu[24]. If the focus is in the frontal cortex, then the seizure is often movement related, so the person may display peddling or kicking movements, their head may turn to one side or they may adopt a strange bodily position, perhaps with one arm straight and one bent.

If the seizure activity propagates to both hemispheres, in what is called a focal impaired awareness seizure, then consciousness will be impaired or lost[2]. Someone having a focal impaired awareness seizure will usually be unresponsive or only partially responsive during the seizure, and will not remember the event afterwards. As in other seizures, the manifestation of the seizure will relate to where the seizure focus is and the degree of propagation.

A person with focal seizures will generally experience the same seizure pattern and symptoms each time they have a focal seizure, but the intensity may vary[24]. While focal seizures are the most common, they are more likely to be refractory to treatment[27]. The reason for this is not known, but a poor prognosis is associated with a chronic history of focal seizures. It is possible that focal seizures may go unrecognised for a longer period than other types of seizures as people may think what they are experiencing is normal.

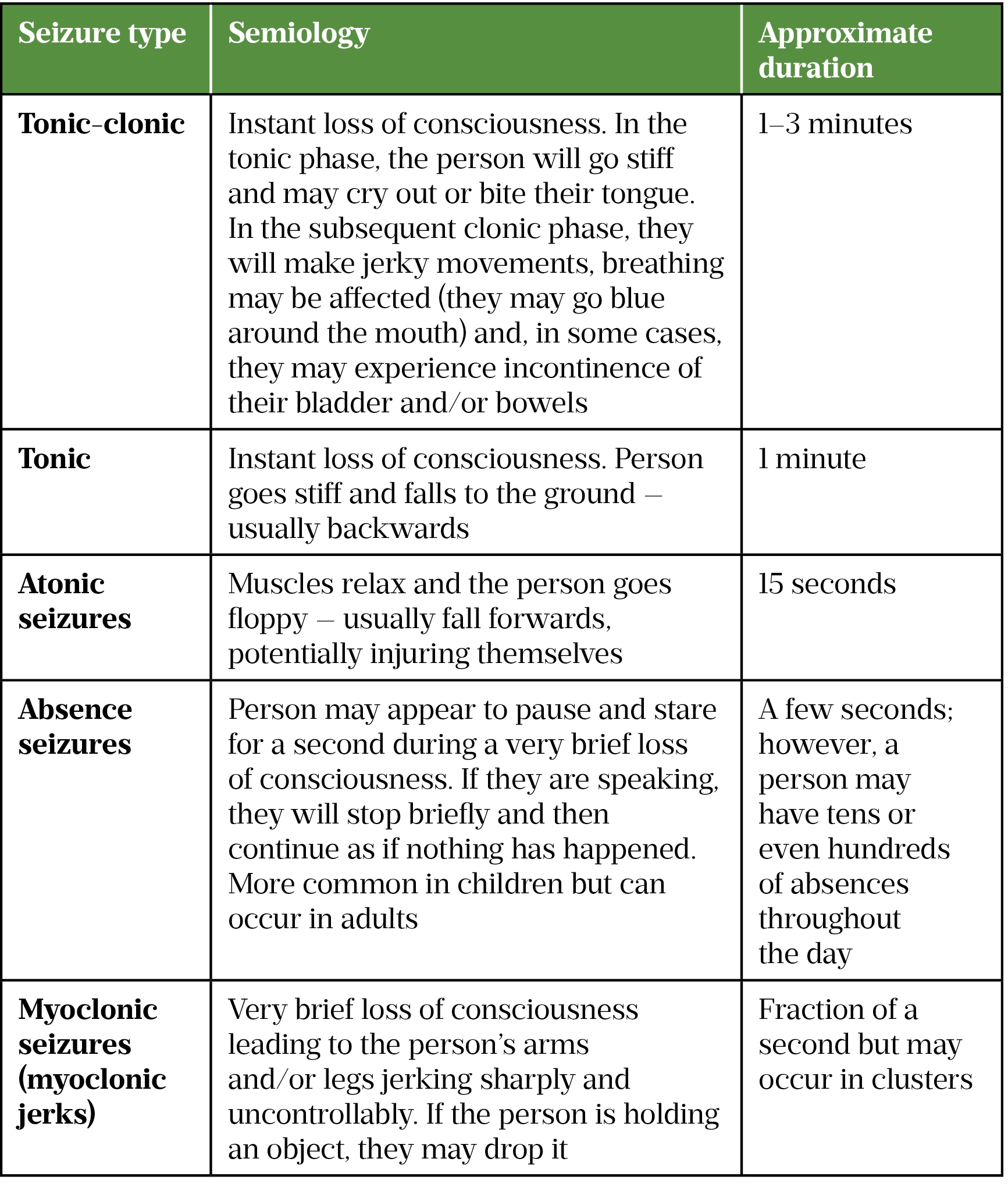

Generalised seizures arise simultaneously from both cerebral hemispheres of the brain, leading to an immediate loss of consciousness. Generalised seizures are also subdivided into different types (see Table).

Some people with epilepsy who experience focal seizures occasionally lose consciousness owing to the spread of seizure activity to both brain hemispheres[2]. On these occasions, the seizure evolves into a bilateral tonic-clonic seizure. For some people who experience focal seizures, this will never happen; for others, it may be more common and follow a period of worsening focal seizures or arise because of a specific trigger.

Recently, a new classification of epilepsy type has been added, recognising that some people experience both focal and generalised seizures[2].

Some people are diagnosed with an epilepsy syndrome and may therefore experience a collection of symptoms and seizure types — a list of epilepsy syndromes is available from the ILAE[2]. Epilepsy syndromes are often diagnosed at a young age and therefore are more common in children. One example that does arise in slightly older children (i.e. aged 12–16 years) is juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME). Most people with JME have three seizure types: absences, myoclonic seizures and tonic-clonic seizures[2].

Seizure triggers

Common seizure triggers include stress, anxiety — including seizure-related anxiety — poor sleep, prolonged periods without food and poor medication adherence[28–31]. Misuse of drugs, particularly stimulants (e.g. cocaine and amphetamines), can trigger seizures and alcohol ingestion, particularly as part of alcohol withdrawal, is commonly associated with seizures[32,33].

Some women experience a worsening of seizure control around the time of menstruation, referred to as catamenial epilepsy[34].

Photosensitive epilepsy is one of the reflex epilepsies and refers to the occurrence of seizures in response to specific afferent stimulus or activity, in this case photic stimulation[35]. Photosensitive seizures can commonly be triggered by television, video games and flickering light, usually in a particular wavelength and/or at a specific flash rate. Photosensitive epilepsy is less common than expected, being present in around 2–14% of people with epilepsy[36]. Photosensitivity is associated with genetic generalised epilepsy (also called idiopathic generalised epilepsy) and is twice as common in women[36].

Diagnosis

There can be complications when diagnosing epilepsy, and misdiagnosis is common. Studies carried out in primary, secondary and tertiary care have reported misdiagnosis rates of between 4.6% and 30%[37].

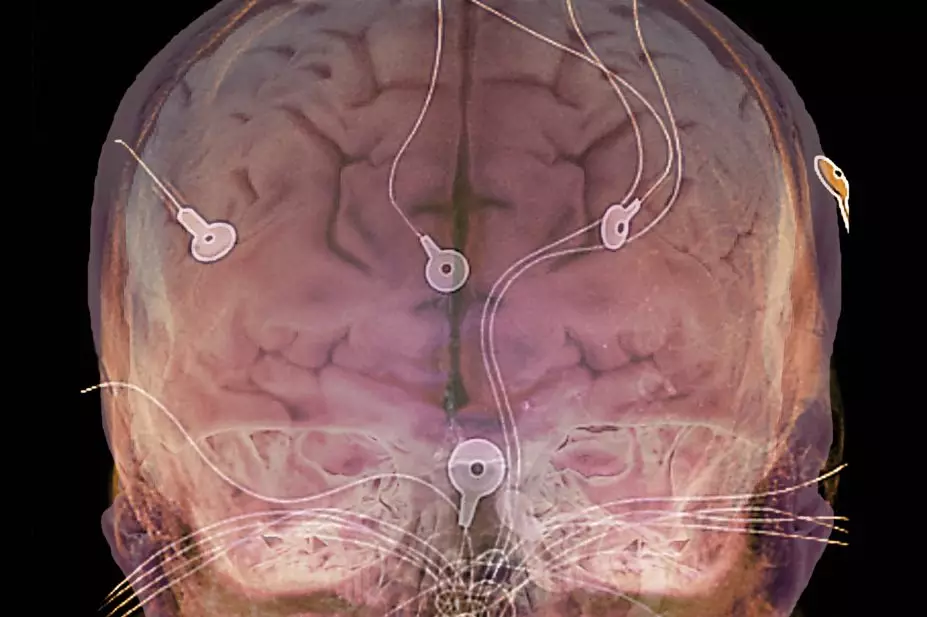

An electroencephalogram (EEG) is carried out when a person is suspected of having epilepsy based on their clinical history; this is usually after an obvious seizure or, in some cases, a ‘funny turn’ — an episode that may initially appear to be a faint or dizzy spell, for example. An EEG can provide information about epilepsy type; however, its use for this indication is limited[38].

During an EEG, electrodes are attached to the surface of the scalp to detect changes in brain electrical patterns indicative of epilepsy. Often, patients do not have inter-ictal (i.e. between seizure) electrical changes; therefore, seizure-indicating patterns are not detected at the time of EEG[39]. It is possible that the abnormal electrical activity may occur deep within the brain, such that the EEG will not detect any seizure patterns. Video-EEG telemetry, carried out in hospital or at home, enables the brain to be monitored via EEG over a period of days, while a camera films the episodes experienced. While this can aid diagnosis, having electrodes fitted and attached for several days and video equipment in the home to record seizures may not be practical for all patients and, in some cases, could still lead to equivocal results and possible misdiagnosis[40].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to help identify any obvious lesions or scarring in the brain that are causing seizures. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that an MRI is carried out in cases where the person developed epilepsy before two years of age or as an adult; if focal epilepsy is suspected; or if seizures continue despite ASM[38].

History of the seizure(s), usually recounted by a witness, is essential for diagnosis. This can be supported by a video of the seizure. Many carers and family report finding the action of taking a video while someone is seizing uncomfortable, as it can feel voyeuristic; however, the advent of mobile phone cameras has improved diagnosis significantly[41].

Differential diagnoses

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES), also called dissociative seizures, non-epileptic attacks or psychogenic seizures, are commonly misdiagnosed as epilepsy in adults and older children[42]. It is important to stress that these are real seizures, but they are not generated by abnormal electrical activity in the brain[42]. PNES commonly arise in response to thoughts and feelings linked to present and past traumatic experiences, including a history of abuse, and are more common in women[43]. It is possible that 10–20% of patients presenting to epilepsy centres may have this diagnosis[44]. Owing to difficulties in diagnosis, a person may have received an epilepsy diagnosis and been treated with ASMs (which do not work for this indication) for many years before a diagnosis of PNES is made. Video-EEG telemetry can distinguish between PNES and epileptic seizures if seizures are captured during recording. EEG indicators of PNES include:

- The length of the seizure — PNES tend to be longer than epileptic seizures;

- Unresponsiveness while the EEG shows the person is not asleep;

- Eye closure in a seizure that is not a generalised tonic-clonic seizure[45].

From the patient’s history, PNES should be suspected if a patient does not respond to ASMs or they have a psychiatric comorbidity[45]. PNES requires specialist input and patients are usually referred to a neuropsychiatrist for psychotherapy and counselling. It is possible for people to experience both epilepsy and PNES.

Syncope (i.e. a temporary loss of consciousness, usually related to insufficient blood flow to the brain) is a common differential diagnosis for someone aged over 18 years who has had a possible first seizure[46]. During a syncopal episode the patient will go limp, which is not a feature of an epileptic seizure. Diagnostic uncertainty can arise, as a high percentage of syncopal episodes feature some form of jerking of the body[46]. Cardiovascular or cerebrovascular causes, such as heart valve disease, cardiomyopathy or cardiac arrhythmia, should be investigated and ruled out before a diagnosis of epilepsy is considered.

Some of the sensations associated with focal seizures are similar to migraine aura and are referred to as seizure aura. There is a higher prevalence of migraine in people with epilepsy and vice versa[47,48]. Some ASMs are used to treat both conditions (e.g. topiramate).

In young children, the differential diagnosis is more likely to involve physical and organic causes for symptoms, including non-epileptic staring spells, parasomnias, tics and gastroesophageal reflux[49].

Complications of epilepsy

Somatic and psychiatric comorbidity is high in people with epilepsy; cognitive conditions are particularly common. Up to half of all patients with epilepsy report some form of memory issue, which can impact daily life as much as seizures themselves[50]. Memory problems can be related to the underlying condition of the brain caused by epilepsy or a short-term seizure effect, as after a seizure a person may be confused or tired. In the longer term, repeated seizures can lead to scarring of brain tissue, which can act as a seizure focus. Some ASMs (e.g. topiramate) can cause memory and other cognitive issues[51].

Depression, anxiety, suicide and suicide ideation, and psychosis all have a higher prevalence in people with epilepsy compared with the general population[4]. Management of mental health conditions alongside epilepsy can be challenging. A phenomenon referred to as ‘forced normalisation’ exists whereby, for example, improving psychosis can result in a worsening of seizure control and, likewise, improvements in seizure control can worsen psychosis[52].

Status epilepticus (SE) is a serious and potentially life-threatening complication of seizures defined as ‘a prolonged seizure or multiple seizures with incomplete return to baseline’[53]. SE occurs when the natural inhibitory mechanisms of the brain fail to overcome the excessive excitation generated in a seizure.

The most serious consequence of a seizure is SUDEP. The SUDEP and Seizure Safety Checklist can help identify modifiable risk factors, which include non-adherence to ASMs, alcohol misuse, depression and other psychiatric disorders, frequent generalised tonic-clonic seizures, and SE/prolonged seizures[54]. Pharmacists can help identify these risk factors and, in some cases, (e.g. adherence) address them.

A recent report showed that in 2016–2018, the number of pregnant women dying from SUDEP almost doubled[55]. Most women had obvious risk factors but had not discussed prevention measures with a healthcare professional or had a medication review[55]. Pharmacists can ask any female patients with epilepsy who are pregnant or considering pregnancy, regardless of the medication that they are taking, whether they have had a medication review with a specialist and advise them to do so if appropriate. This is included in the MHRA valproate guidance for women and girls taking valproate. The pharmacist could offer to contact the woman’s GP or specialist if appropriate.

People with epilepsy are almost ten times more likely to drown than the general population[56]. Pharmacists can provide safety information where appropriate, including taking showers rather than baths where possible, sitting in the shower rather than standing and having someone nearby when bathing, with the door unlocked.

An epilepsy diagnosis can have a significant negative impact on an individual’s life. People with epilepsy report difficulty in maintaining employment and relationships, while stigma and social isolation are prevalent[57]. Pharmacists can advise patients they identify as struggling with the condition to contact their epilepsy specialist nurse if they have one. The UK charities Epilepsy Action and Epilepsy Society also have resources for people with epilepsy and their carers, including a phone helpline. They also help coordinate local groups, which may be useful for people with epilepsy as it can be helpful to speak to others with the condition.

Prognosis

The only cure for epilepsy is surgery, and only in suitable individuals. In some cases, the cause of seizures can be addressed by surgical removal of a lesion, rendering the person seizure-free, although this is not guaranteed. Some epilepsy syndromes of childhood will resolve as the child ages[2]. However, in other cases, the child may go on to develop a different epilepsy syndrome. Many childhood epilepsy syndromes continue into adulthood[2].

For the first time, in 2015, the ILAE defined resolved epilepsy (see Box 1) — this implies that the person no longer has epilepsy, although it does not guarantee that it will not return[2].

What to do if someone has a seizure

A person having a focal aware seizure can usually be assisted to sit or lie down until the seizure has passed. Someone having a focal unaware seizure is unlikely to respond but should be gently steered away from danger (roads, deep water, railway platforms etc.). The person will need someone to stay with them and talk reassuringly to them until they recover, explaining what has happened if they are unsure.

Someone who has a tonic-clonic, tonic or atonic seizure should be protected from injury by removing any harmful objects and cushioning their head with a pillow or piece of clothing. The first aider can time the seizure as they speak calmly to the person having the seizure, staying with them at all times (see Box 2).

Regardless of the seizure type, the person should not be restrained and not given anything to eat or drink until it is clear that it is safe for them to swallow.

An ambulance only needs to be called if it is the person’s first seizure; if the person has injured themselves badly; if the seizure goes on for longer than five minutes; or if the person has a second seizure without recovery from the first.

Box 2: First aid for tonic-clonic seizures

DO

- Protect the person from injury (remove harmful objects from nearby);

- Cushion their head;

- Look for an epilepsy identity card or identity jewellery — it may give information about the person’s seizures and what to do;

- Time how long the clonus (jerking) lasts;

- Put the person in the recovery position once seizure has terminated;

- Stay with the person until they are fully recovered;

- Be calmly reassuring.

DO NOT

- Restrain the person’s movements;

- Put anything in their mouth;

- Try to move them unless they are in danger;

- Give them anything to eat or drink until they are fully recovered;

- Attempt to bring them round.

CALL 999 if

- You know it is the person’s first seizure; or

- The jerking continues for more than five minutes; or

- They have one tonic-clonic seizure after another without regaining consciousness between seizures; or

- They are injured during the seizure; or

- You believe they need urgent medical attention[58].

- 1Epilepsy statistics. Epilepsy Research. 2022.https://epilepsyresearch.org.uk/about-epilepsy/epilepsy-statistics/ (accessed Apr 2022).

- 2Fisher R, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2014;55:475–82. doi:10.1111/epi.12550

- 32016 community survey. Epilepsy Foundation. 2016.https://www.epilepsy.com/sites/core/files/atoms/files/community-survey-report-2016%20V2.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 4Keezer M, Sisodiya S, Sander J. Comorbidities of epilepsy: current concepts and future perspectives. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:106–15. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00225-2

- 5Dafoulas G, Toulis K, Mccorry D, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus and risk of incident epilepsy: a population-based, open-cohort study. Diabetologia 2017;60:258–61. doi:10.1007/s00125-016-4142-x

- 6Verrier R, Pang T, Nearing B, et al. The Epileptic Heart: Concept and clinical evidence. Epilepsy Behav 2020;105:106946. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.106946

- 7Zhao H, Li S, Xie M, et al. Risk of epilepsy in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of population based studies and bioinformatics analysis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2020;11:2040622319899300. doi:10.1177/2040622319899300

- 8Yeh C, Wang H, Chou Y, et al. High risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients with epilepsy: a nationwide cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc 2013;88:1091–8. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.06.024

- 9Thijs R, Surges R, O’Brien T, et al. Epilepsy in adults. Lancet 2019;393:689–701. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32596-0

- 10Kotsopoulos I, van M, Kessels F, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence studies of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures. Epilepsia 2002;43:1402–9. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.t01-1-26901.x

- 11Levira F, Thurman D, Sander J, et al. Premature mortality of epilepsy in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review from the Mortality Task Force of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2017;58:6–16. doi:10.1111/epi.13603

- 12Heaney D, MacDonald B, Everitt A, et al. Socioeconomic variation in incidence of epilepsy: prospective community based study in south east England. BMJ 2002;325:1013–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7371.1013

- 13Thurman D, Logroscino G, Beghi E, et al. The burden of premature mortality of epilepsy in high-income countries: A systematic review from the Mortality Task Force of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2017;58:17–26. doi:10.1111/epi.13604

- 14Nashef L, So E, Ryvlin P, et al. Unifying the definitions of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2012;53:227–33. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03358.x

- 15Thurman D, Hesdorffer D, French J. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: assessing the public health burden. Epilepsia 2014;55:1479–85. doi:10.1111/epi.12666

- 16Rafnsson V, Olafsson E, Hauser W, et al. Cause-specific mortality in adults with unprovoked seizures. A population-based incidence cohort study. Neuroepidemiology 2001;20:232–6. doi:10.1159/000054795

- 17Gorton H, Webb R, Carr M, et al. Risk of Unnatural Mortality in People With Epilepsy. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:929–38. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0333

- 18Neligan A, Bell G, Johnson A, et al. The long-term risk of premature mortality in people with epilepsy. Brain 2011;134:388–95. doi:10.1093/brain/awq378

- 19Fiest K, Sauro K, Wiebe S, et al. Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of international studies. Neurology 2017;88:296–303. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000003509

- 20Robertson J, Hatton C, Emerson E, et al. Prevalence of epilepsy among people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Seizure 2015;29:46–62. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2015.03.016

- 21Hauser W, Annegers J, Kurland L. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935-1984. Epilepsia 1993;34:453–68. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02586.x

- 22Sirven J. Epilepsy: A Spectrum Disorder. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015;5:a022848. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a022848

- 23Epilepsy. World Health Organization. 2022.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy (accessed Apr 2022).

- 24Scheffer I, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017;58:512–21. doi:10.1111/epi.13709

- 25Steinlein O. Genetics and epilepsy. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2008;10:29–38.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18472482

- 26Gaitatzis A, Sisodiya S, Sander J. The somatic comorbidity of epilepsy: a weighty but often unrecognized burden. Epilepsia 2012;53:1282–93. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03528.x

- 27Semah F, Picot M, Adam C, et al. Is the underlying cause of epilepsy a major prognostic factor for recurrence? Neurology 1998;51:1256–62. doi:10.1212/wnl.51.5.1256

- 28Novakova B, Harris P, Ponnusamy A, et al. The role of stress as a trigger for epileptic seizures: a narrative review of evidence from human and animal studies. Epilepsia 2013;54:1866–76. doi:10.1111/epi.12377

- 29Ertan D, Hubert-Jacquot C, Maillard L, et al. Anticipatory anxiety of epileptic seizures: An overlooked dimension linked to trauma history. Seizure 2021;85:64–9. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2020.12.006

- 30Malow B. Sleep deprivation and epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr 2004;4:193–5. doi:10.1111/j.1535-7597.2004.04509.x

- 31Manjunath R, Davis K, Candrilli S, et al. Association of antiepileptic drug nonadherence with risk of seizures in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2009;14:372–8. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.12.006

- 32Alldredge B, Lowenstein D, Simon R. Seizures associated with recreational drug abuse. Neurology 1989;39:1037–9. doi:10.1212/wnl.39.8.1037

- 33Rogawski M. Update on the neurobiology of alcohol withdrawal seizures. Epilepsy Curr 2005;5:225–30. doi:10.1111/j.1535-7511.2005.00071.x

- 34Verrotti A, D’Egidio C, Agostinelli S, et al. Diagnosis and management of catamenial seizures: a review. Int J Womens Health 2012;4:535–41. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S28872

- 35Hanif S, Musick S. Reflex Epilepsy. Aging Dis 2021;12:1010–20. doi:10.14336/AD.2021.0216

- 36Wolf P, Goosses R. Relation of photosensitivity to epileptic syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1986;49:1386–91. doi:10.1136/jnnp.49.12.1386

- 37Chowdhury F, Nashef L, Elwes R. Misdiagnosis in epilepsy: a review and recognition of diagnostic uncertainty. Eur J Neurol 2008;15:1034–42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02260.x

- 38Epilepsies: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg137 (accessed Apr 2022).

- 39Benbadis S, Tatum W. Overintepretation of EEGs and misdiagnosis of epilepsy. J Clin Neurophysiol 2003;20:42–4. doi:10.1097/00004691-200302000-00005

- 40Kanner A. Common errors made in the diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy. Semin Neurol 2008;28:364–78. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1079341

- 41Tatum W, Hirsch L, Gelfand M, et al. Video quality using outpatient smartphone videos in epilepsy: Results from the OSmartViE study. Eur J Neurol 2021;28:1453–62. doi:10.1111/ene.14744

- 42Benbadis S. The differential diagnosis of epilepsy: a critical review. Epilepsy Behav 2009;15:15–21. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.02.024

- 43Bodde N, Brooks J, Baker G, et al. Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures–definition, etiology, treatment and prognostic issues: a critical review. Seizure 2009;18:543–53. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2009.06.006

- 44Benbadis S, Allen H. An estimate of the prevalence of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Seizure 2000;9:280–1. doi:10.1053/seiz.2000.0409

- 45Brunnhuber F. Psychogenic non epileptic seizures: diagnostic approach. In: Alarcon G, Valentin A, eds. Introduction to Epilepsy. Cambridge: : Cambridge University Press 2012. 313–317.

- 46Zaidi A, Clough P, Cooper P, et al. Misdiagnosis of epilepsy: many seizure-like attacks have a cardiovascular cause. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:181–4. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00700-2

- 47Keezer M, Bauer P, Ferrari M, et al. The comorbid relationship between migraine and epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol 2015;22:1038–47. doi:10.1111/ene.12612

- 48Cianchetti C, Pruna D, Ledda M. Epileptic seizures and headache/migraine: a review of types of association and terminology. Seizure 2013;22:679–85. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2013.05.017

- 49Cross J. Differential diagnosis of epileptic seizures in infancy including the neonatal period. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;18:192–5. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2013.04.003

- 50Lodhi S, Agrawal N. Neurocognitive problems in epilepsy. Adv. psychiatr. treat. 2012;18:232–40. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.110.007930

- 51Baker GA, Taylor J, Aldenkamp AP, et al. Newly diagnosed epilepsy: Cognitive outcome after 12 months. Epilepsia. 2011;52:1084–91. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03043.x

- 52Calle‐López Y, Ladino LD, Benjumea‐Cuartas V, et al. Forced normalization: A systematic review. Epilepsia. 2019;60:1610–8. doi:10.1111/epi.16276

- 53Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus – Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56:1515–23. doi:10.1111/epi.13121

- 54McCabe J, McLean B, Henley W, et al. Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) and seizure safety: Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors differences between primary and secondary care. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2021;115:107637. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107637

- 55Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2016–18. MBRRACE-UK. 2020.https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2020/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_Dec_2020_v10_ONLINE_VERSION_1404.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 56Bain E, Keller AE, Jordan H, et al. Drowning in epilepsy: A population-based case series. Epilepsy Research. 2018;145:123–6. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.06.010

- 57Hermann B, Jacoby A. The psychosocial impact of epilepsy in adults. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2009;15:S11–6. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.03.029

- 58What to do when someone has a seizure. Epilepsy Action. 2021.https://www.epilepsy.org.uk/info/firstaid/what-to-do (accessed Apr 2022).