Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, individuals should be able to:

- Help breastfeeding mothers make informed choices regarding the use of both over-the-counter and prescription medicines;

- Understand the pharmacokinetic principles that may impact the transfer of medicines into milk;

- Understand the potential problems of sudden breastfeeding cessation and know how to properly advise mothers on the management of breastfeeding while taking medicines.

Breastmilk is the ideal form of nutrition for infants: the biological norm. Its nutritional composition uniquely caters for the health and growth needs of a baby[1–3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) therefore recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months, with supplemental breastfeeding continuing for two years and beyond[2].

In the Lancet series on breastfeeding, the executive summary stated that “breastfeeding has proven health benefits for both mothers and babies in high-income and low-income settings alike”[4]. The series drew attention to the highly effective advertising strategies used by commercial formula manufacturers to target parents, healthcare professionals and policy-makers[5].

A 2011 report by Renfrew et al. concluded that if half of UK mothers, who do not currently breastfeed, were to do so for up to 18 months over their lifetime period of lactation, there would be 865 fewer cases of breast cancer per year, potentially saving lives while providing more than £21m in cost savings to the NHS each year[6].

Renfrew et al. further deduced that if 45% of babies were exclusively breastfed for their first four months of life, and if 75% of babies in neonatal units were breastfed at discharge, each year there would be fewer babies hospitalised with gastroenteritis and respiratory illnesses, as well as a reduction in children assessed for ear infections by GPs, with huge cost-saving implications[6].

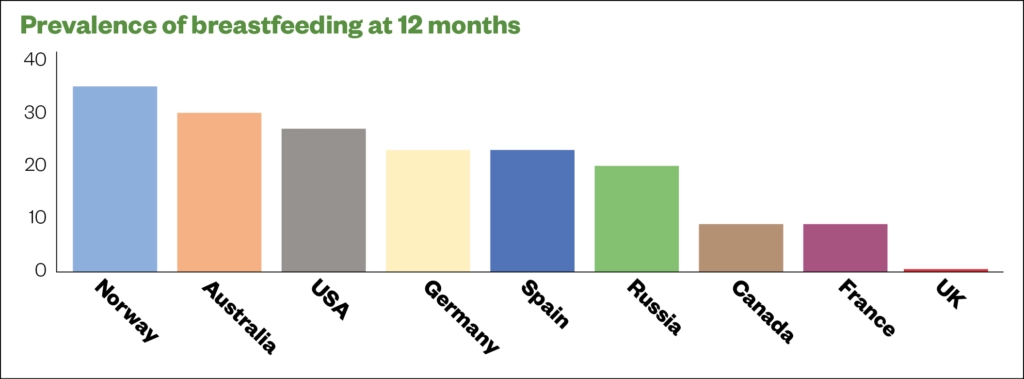

Currently, more than 80% of UK mothers initiate breastfeeding after delivery; however, prevalence falls rapidly in the first few weeks[7,8]. Data suggest that 31.5% of babies are breastfed exclusively at 6 weeks, reducing to 0.5% at 12 months — these figures are among the lowest globally (see Figure 1)[9,10].

Source: Lancet[10]

The use of many medicines in breastfeeding women falls outside of the product licence and is of concern for all healthcare professionals. Patient information leaflets for products, such as glycerine, honey and lemon linctus, cough lozenges or simple linctus, contain warnings that these medicines should not be used by breastfeeding women, owing to any potential risk of infant exposure to the drug. However, this does not mean these medicines cannot be used; instead, pharmacokinetic properties should be considered, specialist resources consulted (e.g. HalesMeds, LactMed database and UK Drugs in Lactation Advisory Service) and professional responsibility taken.

This article outlines the pharmacokinetic principles influencing a drug’s passage through breast milk, as well as the factors that should be considered when discussing the compatibility of a medicine — whether over-the-counter (OTC) or prescribed — and the potential side effects on a lactating mother.

Concerns about medication in lactation

During the first-wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, anecdotal feedback from the Breastfeeding Network Drugs in Breastmilk service reported that breastfeeding was not discussed during video consultations between healthcare professionals and lactating mothers, and that women only raised concerns about medicines after reading patient information leaflets[11]. Mothers also reported delays in call backs regarding the compatibility of a drug with breastfeeding, which had not been mentioned during the consultation[11]. A delay may have led to the mother not taking the drug immediately, or choosing not to take it at all; the mother taking an inappropriate drug and potentially exposing the baby to a drug incompatible with breastfeeding; or unnecessary interruption or cessation of breastfeeding.

A PhD study conducted in 2000 found that 28.1% (n=124) of mothers who purchased a medication from a pharmacy were not asked if they were breastfeeding, and 16% (n=131) were not asked about their infant feeding method before being issued with a prescription[12].

Health promotion and interactions with new parents present opportunities for pharmacists to promote safe and appropriate use of medicines while breastfeeding. Mothers value the availability of pharmacists and trust them to provide accurate, evidence-based information that may reinforce information their GP has provided about medicines safety in lactation.

Pharmacists should therefore take the following factors into account and present the evidence as part of a shared decision-making approach with mothers, to aid them in making an informed decision.

Licensing of medication

Most medicines are not licensed for use during lactation. It would be unethical to expose a baby to anything through its mother’s milk without knowing the effect; however, over time, research and case studies are usually published in specialist resources that enable assessment of compatibility (see ‘Useful resources’).

Although a medicine’s licence does not change, it is possible to use professional judgement to recommend whether:

- A medication is suitable for a breastfeeding mother;

- An alternative would be preferable;

- To suspend breastfeeding or decide to wait rather than treat the mother immediately.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of the British National Formulary (BNF) as a guide only, as it does not contain quantitative data on which to base individual decisions[13].

The information within the BNF monograph is usually based on the summary of product characteristics. For example, the entry for ibuprofen states:

“With oral use: Use with caution during breastfeeding. Amount too small to be harmful but some manufacturers advise avoid.

With topical use in adults: Patient packs for topical preparations carry a warning to avoid during breastfeeding.”[14]

Ibuprofen is recommended to mothers in the immediate post-partum period for perineal pain, pain after a caesarean section and to treat the early signs of mastitis, as so little of the drug passes into breast milk[15]. Topical products are poorly absorbed so the amount absorbed into milk from a gel is considered negligible[16,17].

Pharmacists should use professional judgement and explain to the mother why the medicine can be used safely, and that professional advice may be different to that on the leaflet, based on an understanding of drug pharmacokinetics affecting transfer into milk. The power of the written word, social media and the internet cannot be underestimated and, if reassurance is required, pharmacists can contact the UK Drugs in Lactation Advisory Service, which is part of the UK Medicines Information service, for further information and discussion on compatibility of medicines during lactation.

Pharmacokinetics of drugs affecting transfer into milk

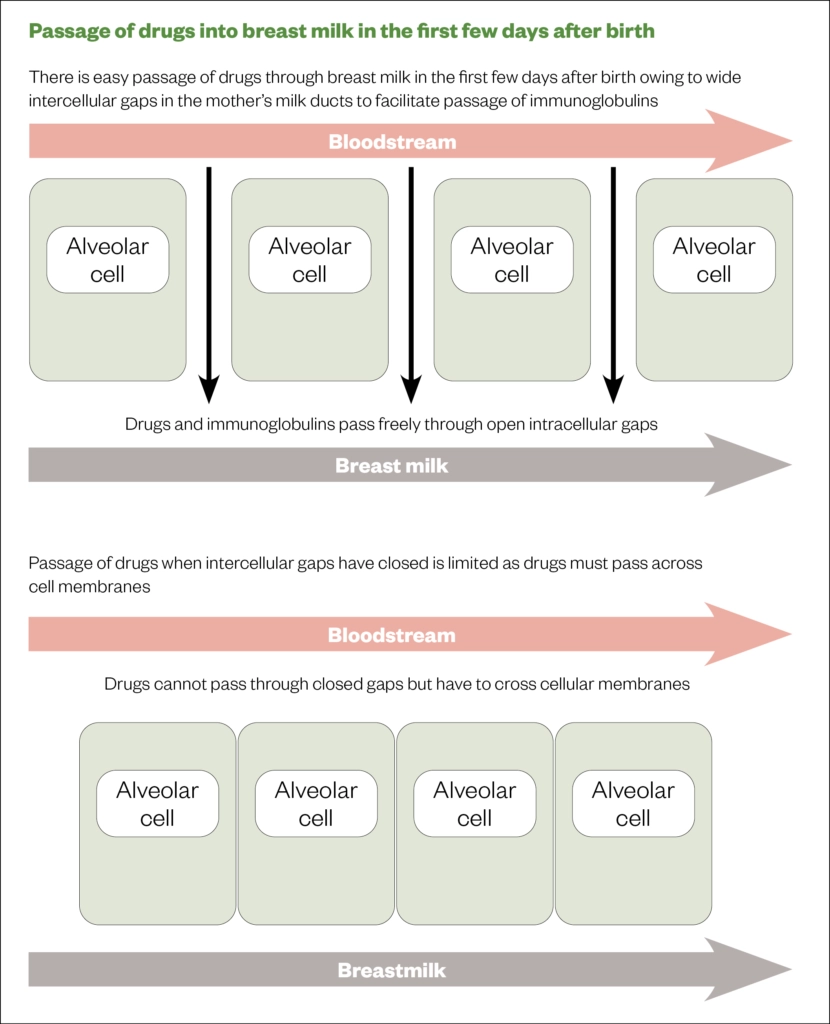

Babies are most vulnerable to the effects of medication in the first few days after delivery as the intercellular gaps in the milk ducts are wide open, allowing large molecules such as immunoglobulins to pass through into the breast milk (see Figure 2). Immunoglobulins protect the baby from infection and pass on immunity. However, it is during these first few days after birth that most medication is given to lactating women. In one study, 56.5% of mothers (n=463) recalled being given medication in the early puerperium — predominantly antibiotics and analgesics[13]. In addition, a study by Passmore et al. reported that 97% of women were given at least one drug in the first week after birth[18].

Prescribing within the maternity unit is common, and follows standard procedures and formularies, which are shared by prescribers. Within primary care prescribing, decisions are made by individuals who may be less confident prescribing for lactating mothers, resulting in cautionary and unnecessary advice to interrupt or stop breastfeeding based on the limited information in the BNF. Prescribers are aware that prescribing in lactation may involve exposure to the baby and will attempt to protect them. However, asking the mother to suddenly stop breastfeeding may cause mastitis, meaning that there may be unexpected consequences when trying not to cause harm to the baby.

Source: Breastfeeding and medication[17]

To avoid potential risks, it is important to review pharmacokinetic data before recommending or prescribing a medicine to a breastfeeding mother. This information is available in Martindale and in specialised texts (see ‘Useful resources’)[19]. Particular attention should be given to:

- Oral bioavailability — if this is negligible (e.g. infliximab, insulin, low molecular weight heparinoids) then the baby is unable to absorb any of the drug that has passed into milk;

- Plasma protein binding — the more highly bound a drug is, the less can transfer into milk (e.g. ibuprofen >99% bound);

- Milk plasma ration — the lower this value is, the smaller the amount of the drug present. Iodine has a milk plasma ratio of 26, demonstrating an active transport mechanism into milk, which is why iodine dressings should not be recommended for lactating mothers. Most drugs have a milk-to-plasma ratio <1 (e.g. sertraline 0.89);

- Molecular weight — a large weight is normally indicative of low oral bioavailability (e.g. enoxaparin has a molecular weight of 8,000);

- Whether it is subject to extensive first pass metabolism — this limits the amount available to be absorbed by the baby (e.g. morphine);

- Relative infant dose — a level <10% is a marker of compatibility with lactation (e.g. sertraline 0.4–2.2%)[17,19,20].

If a drug is licensed for paediatric use, the amount transferred into milk is likely significantly less than the licensed dose (e.g. 2.9micrograms/kg of loratadine following maternal consumption, compared with 5mg at age 2 years [average weight 12 kg])[21].

Similarly, when considering medication for a lactating mother, there is a considerable difference between risks to a pre-term baby born at 28 weeks gestation, a healthy exclusively breastfed baby of six weeks and a toddler feeding around three times per day, alongside a weaning diet.

If mother and baby are prescribed the same drugs (e.g. antibiotics, paracetamol and ibuprofen), the therapeutic index should be considered. The amounts transferred to milk from the examples is low, meaning that use by the mother will not add significantly to that of a healthy term baby.

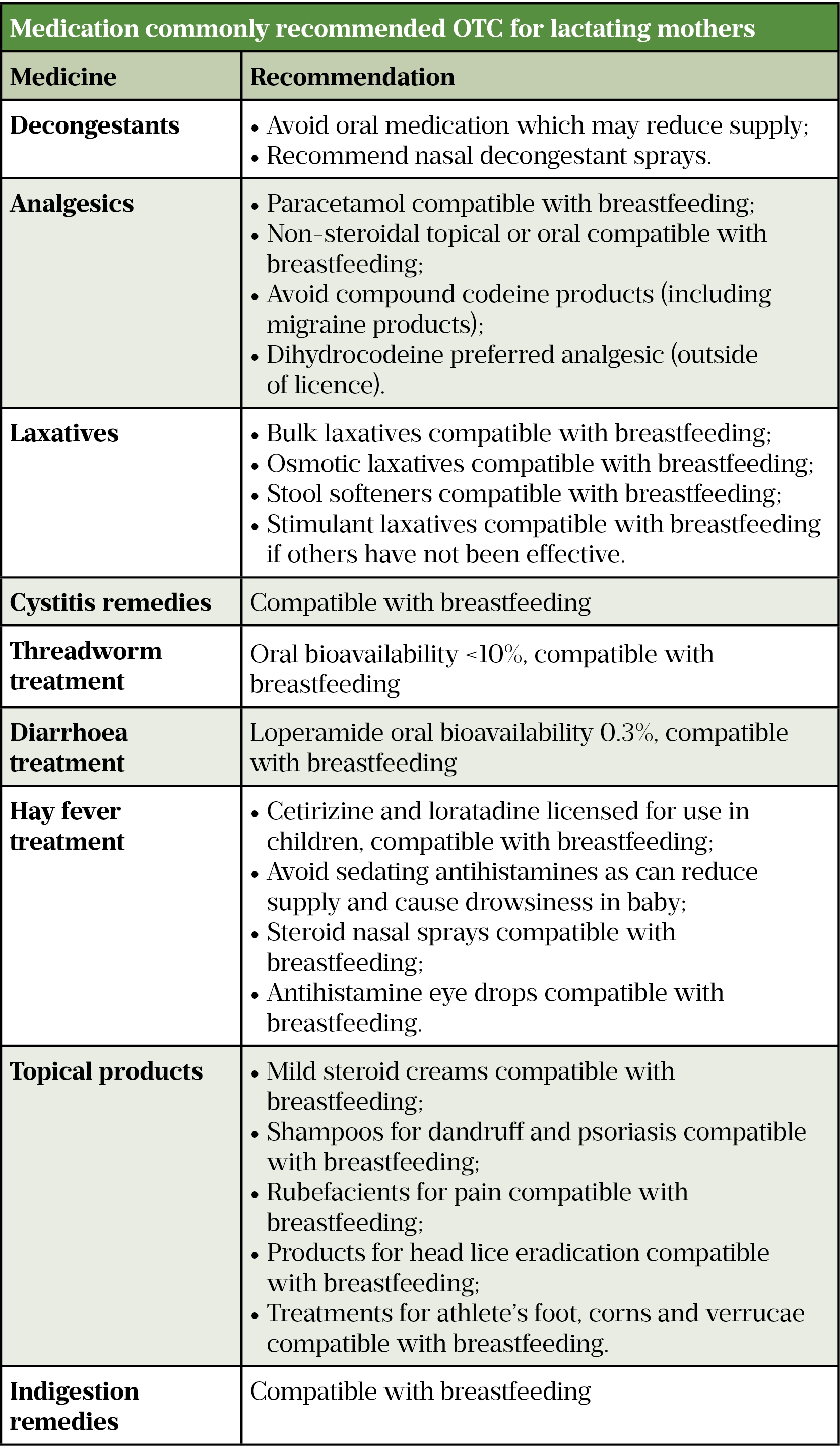

Over-the-counter medicines

Despite being unlicensed, most OTC medicines can be used by breastfeeding mothers; for example, mebendazole has an oral bioavailability of 2–10%, and bulk forming and osmotic laxatives do not pass significantly into milk[20,22,23]. Table 1 provides a summary of advice for commonly recommended OTC medicines; most products are outside of product licence during lactation.

Sources: Breastfeeding and medication[17], Martindale[19], Hale’s medications & mothers’ milk[20]

Codeine should not be recommended as metabolism varies between individuals and some breastfeeding mothers may concentrate the drugs into milk[24,25]. Sadly, this is highlighted in a case where a baby died after the mother took codeine postnatally, on the advice of a paediatrician, which led to the baby being exposed to higher levels of morphine than expected as the mother was an ultra-rapid metaboliser[26,27]. In 2013, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) recommended that codeine is avoided during lactation as breastfed babies may “very rarely develop side effects due to the presence of morphine in breastmilk”[28,29]. Instead, if a mother requires opioid pain relief, dihydrocodeine is preferred. Dihydrocodeine has an oral bioavailability of 20% and is metabolised in the liver by CYP2D6 to dihydromorphine, which has potent analgesic activity. The metabolism of dihydrocodeine is not affected by individual metabolic capacity as the analgesic effect is produced by the parent drug, whereas codeine is a pro-drug[19].

Medicines that have the potential to cause drowsiness (e.g. chlorpheniramine and diphenhydramine) should be avoided, as they can pass the blood-brain barrier, causing sedation in the child. These medicines may also have the potential to reduce milk supply[17,20].

Herbal remedies do not have the same levels of available data on use in breastfeeding and are best avoided during breastfeeding[17].

Prescribed medicines

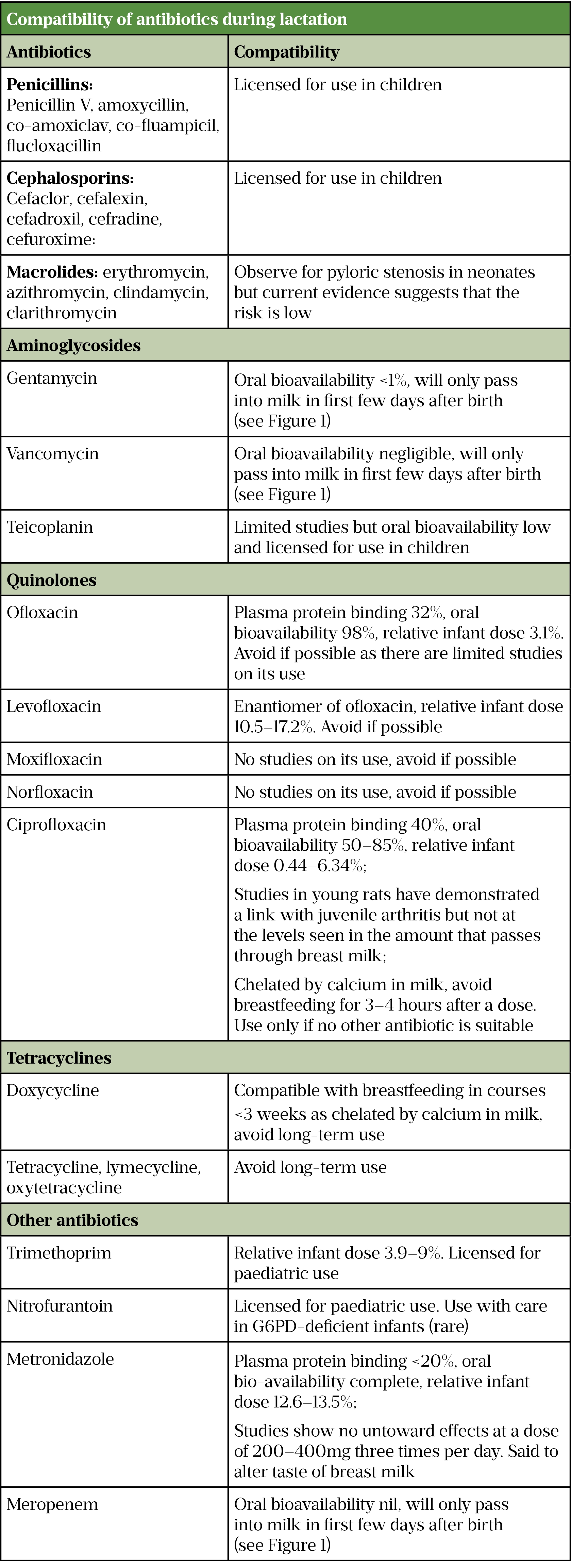

Antibiotics are given to many breastfeeding mothers for uterine infections (often cephalexin and metronidazole), mastitis (usually flucloxacillin) or infections that affect the general population. The amount of antibiotics passing through breast milk damages the gut villae of the baby, causing temporary lactose intolerance resulting in loose, runny bowel motions. This is inconvenient, but not a reason to interrupt breastfeeding. Breast milk contains all of the factors needed to redress the gut balance without further treatment. Any antibiotic that is licensed to be given to a child can be given to a breastfeeding mother, as levels reaching the baby through milk will be lower than the licensed dose[30,31].

Ito et al. studied a group of 125 mothers, who had been informed that their prescribed antibiotics were compatible with breastfeeding[32]. Regardless of the advice, 15% (n=19) chose not to take the antibiotics and 7% (n=7) stopped breastfeeding during the course. Table 2 provides a summary of the compatibility of antibiotics for use during lactation.

Sources: Breastfeeding and medication[17], Martindale[19], Hale’s medications & mothers’ milk[20], Eur J Pediatr[33]

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Around 20% of people contacting the Breastfeeding Network Drugs in Breastmilk service are looking for information on the treatment of anxiety and depression[34]. Sertraline or citalopram are the first-line drugs of choice during breastfeeding to treat anxiety and depression; they are well studied and little passes into breast milk[35–37]. Lithium is contraindicated in breastfeeding as cases of toxicity have been reported in newborns[20]. Clozapine is also contraindicated owing to limited published data; however, in one mother taking clozapine 50mg per day, the milk-to-plasma ratio was calculated to be 4.3, suggesting that it concentrates in breast milk[21]. Lithium and clozapine are used in bipolar disease[38]. For further information, see the Royal College of General Practitioners Perinatal Mental Health Toolkit[39]. Stopping breastfeeding can exacerbate symptoms of depression, owing to the loss of oxytocin. Breastfeeding may have a positive effect on the mother’s mental health[40].

Methadone

Methadone is highly plasma protein bound and has a relative infant dose of 1.9–6.5%, meaning that it can be used by a breastfeeding mother if prescribed by a specialist service. Illicit drug use is complicated by the inclusion of possible unknown adulterants[20].

Other drug classes

Breastfeeding mothers may be prescribed a variety of drugs — it is vital that pharmacists feel confident when providing patients with advice and can signpost them to useful resources. The Breastfeeding and Medication website has produced factsheets on opiates, anti-epileptic drugs, carbimazole, diabetes and many others that can be recommended to patients[41–44].

How to advise mothers on managing breastfeeding

Mothers who must interrupt breastfeeding temporarily should be referred to a breastfeeding support practitioner to maintain their supply. Not all women are able to express milk, despite the use of breast pumps. The mechanism of sucking for a baby is different when using a bottle compared with the breast, and not all are willing to take formula milk. Suggesting that a mother does not feed for a few days should not be taken lightly. NICE recommends that healthcare professionals should recognise that there may be adverse health consequences for both mother and baby if the mother does not breastfeed, and that it may not be easy for the mother to stop breastfeeding abruptly and is difficult to reverse[13].

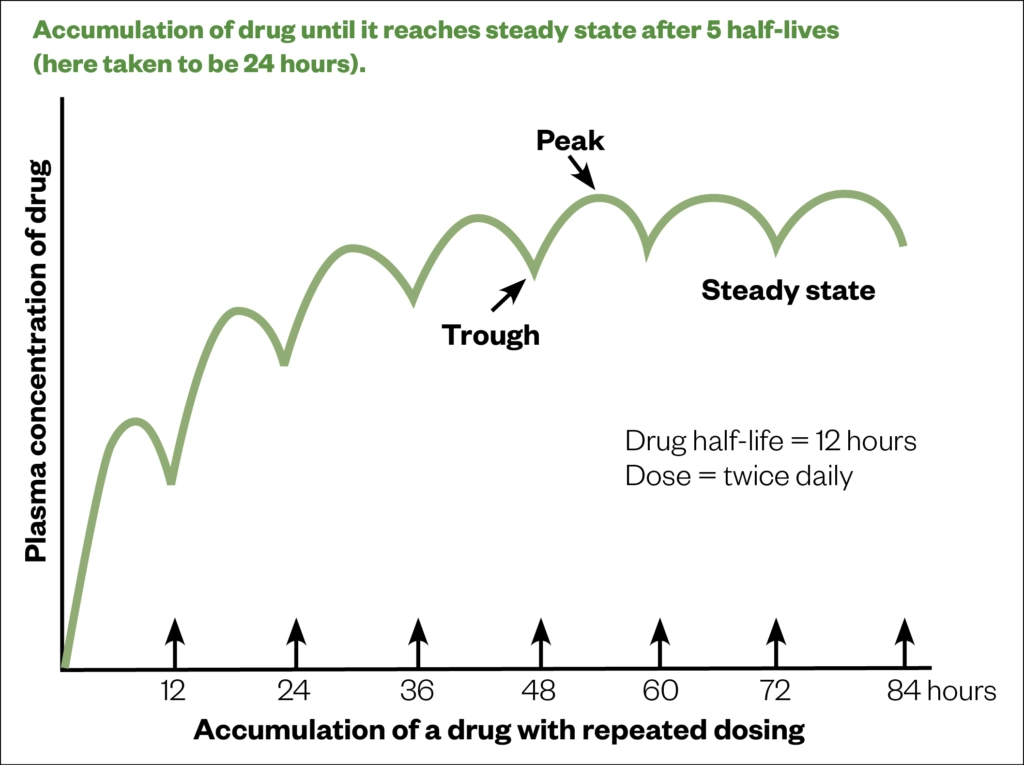

Timing breastfeeds with taking medication is unhelpful if the course exceeds five half-lives of the drug (see Figure 3), after which it reaches a steady state [43]. Anecdotally, this is often recommended to mothers requiring antidepressants.

Source: Breastfeeding and chronic medical conditions[45]

Summary

Medicines use plays an important role in women’s decisions to start or continue breastfeeding. Some may stop breastfeeding or the medicine to avoid combining the two, as they feel very strongly about tainting their milk when breastfeeding[12].

Women deserve to be involved in discussions on compatibility, using evidence-based resources presented in a manner in which they can understand.

There is a presumption by some healthcare professionals, mothers, families and wider society that formula has benefits over breast milk with a trace of medication in, or that adverse events are likely and serious if this breast milk is consumed. In addition, there is a reticence from healthcare professionals to use professional judgement and go outside the licence application for medicines. This leaves the mother with a dilemma: to interrupt or stop breastfeeding to take the medication, or to delay medication — with chronic diseases, the latter is rarely an acceptable option.

In January 2021, the MHRA launched the Safer Medicines Consortium, owing to the “need for reliable and consistent information about medicines used before or during pregnancy and breastfeeding for women and the healthcare professionals who advise them”. The vision of the consortium is that “all women will have access to accurate and accessible information to make informed decisions with their healthcare professional about taking medicines before or during pregnancy or breastfeeding”[46].

As experts in medicines, pharmacists should share evidence-based information with the mother and support her in making a decision that is right for her and her baby, as outlined above.

Useful resources

- UK Drugs in Lactation Advisory Service — NHS information service on drugs in lactation, part of the Specialist Pharmacy Service, has freely available factsheets and a telephone service

- LactMed — a free searchable database, part of the National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Brown A and Jones W (eds). A guide to supporting breastfeeding for the medical professional. London: Routledge; 2019

- The Breastfeeding Network Drugs in Breastmilk Service provides freely available factsheets and social media support

- Breastfeeding and Medication provides freely available factsheets, education and social media support

How to have effective consultations on contraception in pharmacy

What benefits do long-acting reversible contraceptives offer compared with other available methods?

Community pharmacists can use this summary of the available devices to address misconceptions & provide effective counselling.

Content supported by Bayer

This article was originally published in May 2021. It was updated in June 2023.

- 1Prüss-Üstün A, Corvalán C. Preventing disease through healthy environments: Towards an estimate of the environmental burden of disease. World Health Organization. 2006.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43457 (accessed May 2021).

- 2Infant and young child feeding . World Health Organization. 2020.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding (accessed May 2021).

- 3Breastfeeding: a missed opportunity for global health. The Lancet 2017;390:532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32163-3

- 4Breastfeeding 2023. The Lancet. 2023.https://www.thelancet.com/series/Breastfeeding-2023 (accessed Jun 2023).

- 5The Lancet. Unveiling the predatory tactics of the formula milk industry. The Lancet. 2023;401:409. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(23)00118-6

- 6Renfrew M, Pokhrel S, Quigley M, et al. Preventing disease and saving resources: the potential contribution of increasing breastfeeding rates in the UK . UNICEF. 2012.https://www.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2012/11/Preventing_disease_saving_resources.pdf (accessed May 2021).

- 7Hansen K. Breastfeeding: a smart investment in people and in economies. The Lancet 2016;387:416. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00012-X

- 8McAndrew F, Thompson J, Fellows L. Infant feeding survey. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre. 2010.https://sp.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/7281/mrdoc/pdf/7281_ifs-uk-2010_report.pdf (accessed May 2021).

- 9Breastfeeding at 6 to 8 weeks after birth: annual data. Public Health England. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/breastfeeding-at-6-to-8-weeks-after-birth-annual-data (accessed May 2021).

- 10Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet 2016;387:475–90. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01024-7

- 11The breastfeeding network drugs in breastmilk service. Facebook. 2021.https://www.facebook.com/BfNDrugsinBreastmilkinformation/ (accessed May 2021).

- 12Jones W. Community pharmacy support for breastfeeding mothers requiring medication. 2000.

- 13Maternal and child nutrition public health guideline [PH11]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph11 (accessed May 2021).

- 14Ibuprofen. British National Formulary. 2021.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/ibuprofen.html (accessed May 2021).

- 15Inch S, Fisher C. Mastitis: infection or inflammation? Practitioner 1995;239:472–6.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7659673

- 16Stoukides C. Topical Medications and Breastfeeding. J Hum Lact 1993;9:185–7. doi:10.1177/089033449300900324

- 17Jones W. Breastfeeding and medication. London: : Routledge 2018.

- 18Passmore C, McElnay J, D’Arcy P. Drugs taken by mothers in the puerperium: inpatient survey in Northern Ireland. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;289:1593–1596. doi:10.1136/bmj.289.6458.1593

- 19Brayfield A, editor. Martindale: the complete drug reference. 39th ed. London: : Pharmaceutical Press 2017.

- 20Hale T. Hale’s medications & mothers’ milk. 19th ed. New York, USA: : Springer Publishing 2021.

- 21Hilbert J, Radwanski E, Affrime MB, et al. Excretion of Loratadine in Human Breast Milk. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1988;28:234–9. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb03138.x

- 22The Breastfeeding Network factsheet constipation and breastfeeding. Breastfeeding Network. 2019.https://www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/constipation/ (accessed May 2021).

- 23Safety in lactation: laxatives . UKDILAS. 2020.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/safety-in-lactation-laxatives/ (accessed May 2021).

- 24Safety in lactation: opioid analgesics . UKDILAS . 2020.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/safety-in-lactation-opioid-analgesics/ (accessed May 2021).

- 25The Breastfeeding Network factsheet analgesics and breastfeeding. Breastfeeding Network . 2020.https://www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/analgesics/ (accessed May 2021).

- 26Koren G, Cairns J, Chitayat D, et al. Pharmacogenetics of morphine poisoning in a breastfed neonate of a codeine-prescribed mother. The Lancet 2006;368:704. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69255-6

- 27Madadi P, Moretti M, Djokanovic N, et al. Guidelines for maternal codeine use during breastfeeding. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:1077–8.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19910591

- 28PRAC recommends restricting the use of codeine when used for pain relief in children. European Medicines Agency. 2013.www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2013/06/news_detail_001813.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1 (accessed May 2021).

- 29Codeine for analgesia: restricted use in children because of reports of morphine toxicity. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2013.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/codeine-for-analgesia-restricted-use-in-children-because-of-reports-of-morphine-toxicity (accessed May 2021).

- 30The Breastfeeding Network factsheet antibiotics and breastfeeding. Breastfeeding Network. 2020.https://www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/antibiotics/ (accessed May 2021).

- 31Are penicillins and cephalosporins safe in breastfeeding? UKDILAS. 2015.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/are-penicillins-and-cephalosporins-safe-in-breast-feeding/ (accessed May 2021).

- 32Ito S, Koren G, Einarson TR. Maternal Noncompliance with Antibiotics during Breastfeeding. Ann Pharmacother 1993;27:40–2. doi:10.1177/106002809302700110

- 33Abdellatif M, Ghozy S, Kamel MG, et al. Association between exposure to macrolides and the development of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr 2018;178:301–14. doi:10.1007/s00431-018-3287-7

- 34Brown A, Finch G, Trickey H, et al. A lifeline when no one else wants to give you an answer’. An evaluation of the Breastfeeding Network drugs in breastmilk service. The Breastfeeding Network. 2019.https://breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/wp-content/pdfs/BfN%20Executive%20summary.pdf (accessed May 2021).

- 35Jones W. Breastfeeding and medication factsheet sertraline. Breastfeeding and medication. 2021.https://breastfeeding-and-medication.co.uk/fact-sheet/sertraline-and-breastfeeding (accessed May 2021).

- 36Jones W. Breastfeeding and medication factsheet citalopram. Breastfeeding and medication. 2021.https://breastfeeding-and-medication.co.uk/fact-sheet/citalopram-and-breastfeeding (accessed May 2021).

- 37Fenner S. Safety in lactation: antidepressants. UKDILAS. 2020.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/safety-in-lactation-antidepressants/ (accessed May 2021).

- 38Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. Clinical guideline [CG192]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192 (accessed May 2021).

- 39Perinatal mental health toolkit. Royal College of General Practitioners. 2021.https://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/resources/toolkits/perinatal-mental-health-toolkit.aspx (accessed May 2021).

- 40Brown A. Why breastfeeding grief and trauma matter. London: : Pinter & Martin 2019.

- 41Opiates and the breastfeeding mother. Breastfeeding and medication. 2019.https://breastfeeding-and-medication.co.uk/thoughts/opiates-and-the-breastfeeding-mother (accessed May 2021).

- 42Anti-epilepsy medication and breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and medication. 2019.https://breastfeeding-and-medication.co.uk/fact-sheet/anti-epilepsy-medication-and-breastfeeding (accessed May 2021).

- 43Carbimazole in women of childbearing age. Breastfeeding and medication. 2020.https://breastfeeding-and-medication.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/carbimazole-and-pregnancy.pdf (accessed May 2021).

- 44Diabetes and breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and medication. 2020.https://breastfeeding-and-medication.co.uk/fact-sheet/diabetes-and-breastfeeding (accessed May 2021).

- 45Jones W. Breastfeeding and chronic medical conditions. Independently published 2020.

- 46Safer medicines in pregnancy and Breastfeeding Consortium information strategy. MHRA. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/safer-medicines-in-pregnancy-and-breastfeeding-consortium/safer-medicines-in-pregnancy-and-breastfeeding-consortium-information-strategy (accessed May 2021).

2 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Very informative article.

Need to be read by all physicians, pharmacists and nurses too

Thank you