The Pharmaceutical Journal

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand how the workplace is seen from a neurodivergent perspective;

- Understand how simple adjustments can support neurodivergent colleagues;

- Make the pharmacy work environment more inclusive for neurodivergent people.

Introduction

Neurodiversity describes the differences between human brains and celebrates the different ways in which different people see the world1. Most of the population can be described as ‘neurotypical’, and the minority that diverge neurologically from this can be described as ‘neurodivergent’2.

In the UK, it is estimated that one in seven people are neurodivergent3, although many go through life without a formal diagnosis. For example, only 120,000 UK adults have been formally diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but the actual number of adults with ADHD is believed to be around 2.6 million4,5.

All employers are legally obligated to provide reasonable adjustments for staff with disabilities, but bias and discrimination mean that three in five disabled people do not disclose their disability to employers6. It is likely that many pharmacy teams are therefore neurodiverse, even if management is not aware of this, but specific data are absent; a 2023 survey by the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) found that the majority of registered pharmacists and pharmacy technicians chose the option ‘prefer not to say’ or did not record any answer about whether they have a disability (see Table)7. The data gathered by the GPhC on disability do not record the different types (e.g. physical, hearing or visual impairment or neurodivergence).

Neurodiverse teams have been shown to be 33% more efficient8; however, standard workplace procedures and customs can interfere with neurodivergent people’s ability to work to their full potential. Neurodivergent people are up to three times more likely to be bullied than neurotypical people, which can lead to low self-esteem and vulnerability9.

This article explains the changes that can be made to the pharmacy workplace to make it more inclusive for neurodivergent colleagues, focusing on changes that would be useful specifically for people with autism, ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia and sensory-processing differences.

How to create an inclusive pharmacy environment

Unless they choose to disclose this information, it is not possible to know if there are any neurodivergent colleagues within a pharmacy team. Neurodivergence does not always look like the stereotypes we see in the media and neurodivergent colleagues are highly likely to copy neurotypical traits and suppress neurodivergent traits or ‘mask’ to fit into the society around them10. Fearing discrimination, neurodivergent colleagues may choose not to let their managers or fellow colleagues know and others may not know themselves that they are neurodivergent10.

Workplaces need to be inclusive for everyone and this ensures that neurodivergent people can thrive at work regardless of whether they (or their managers) know they are neurodivergent. People should not have to ask for everything they need, as it should already be in place11. As business owners and managers, it is important to get to know colleagues’ communication and learning preferences. The ‘Manual of Me’ is a useful, free resource that can help pharmacy team members identify and communicate these preferences12.

Use of neuro-affirming language

Language is important when addressing colleagues and patients. In general, the neurodiverse community uses neuro-affirming, identity-first language. This means referring to an ‘autistic person’, not a ‘person with autism’. The phrase ‘person with autism’ could be taken to imply that there is something wrong with that person that needs fixing; neurodivergent people are not broken — they are different, not less13.

The term ‘with autism’ feeds into the medical model of disability rather than the societal model, which is more representative and inclusive. This societal model of disability describes a world that is disabling to neurodivergent people, necessitating the requirement for reasonable adjustments to support disabled people14. It is, however, important to reflect a person’s own language.

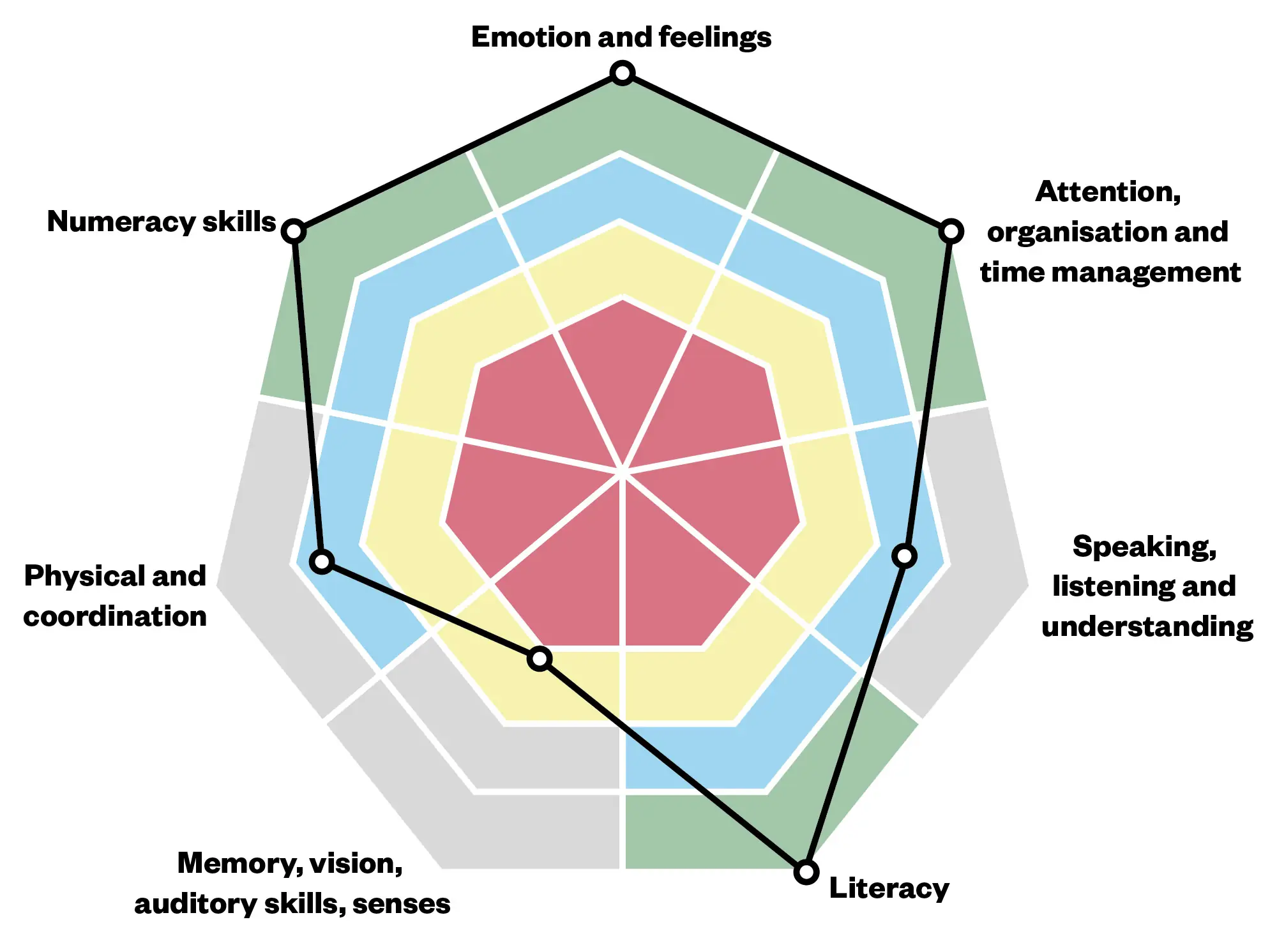

It is also important to stay up to date with terminology. For example, ‘Asperger’s syndrome’ is no longer used as a diagnosis because it has been merged with others into autism spectrum disorder15. Other out-of-date terms include ‘high functioning’ and ‘low functioning’ — the correct term is ‘high and low support needs’, which more accurately aligns with the neurodivergent experience. Support needs differ between individuals and will change throughout life; they can even change monthly16. Instead of thinking of the autism spectrum as linear, with people being ‘more’ or ‘less’ autistic, the neurodivergent community talks of ‘spiky profiles’ (see Figure)17. This refers to the fact that all people, both neurodivergent and neurotypical, have different strengths and weaknesses18.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Understand there are different approaches to communication

Communication issues between neurodivergent and neurotypical people are often referred to as the ‘double empathy problem’19. Communication issues have historically been seen as a problem that neurodivergent people must learn to overcome to fit into a neurotypical society, when in fact it is the responsibility of all people to better understand each other and be open-minded when judging how best to communicate.

For example, when beginning a conversation, neurotypical people often cycle through small talk before moving on to the main subject, whereas neurodivergent people tend to prefer meaningful conversation, often about their special interests, which they may talk about at length (commonly referred to as ‘infodumping’)20. Eye contact is often described as an important component of effective communication but this can be difficult for many neurodivergent people. Some choose to avoid it altogether, or they may concentrate so intently on achieving the ‘correct’ level of eye contact that they miss important points in the conversation19.

It is a common neurotypical trait in the UK to ‘sugar coat’ or speak indirectly about a sensitive point, because it is seen as more polite. This can be confusing for neurodivergent people, who often rely on literal, direct language and their own directness is sometimes misinterpreted as rudeness. Neurotypical people also tend to use more implications, innuendo and changes in tone when speaking. Neurodivergent people may not use or understand tone. On the other hand, some neurodivergent people can be hypersensitive to tone; therefore, clear and specific language, without idioms or colloquialisms should be used19.

Empathy can also manifest differently: while neurotypical people typically mirror emotions and focus on the person, neurodivergent people may show empathy by retelling a related story; this can be perceived as selfish but is simply a different way of showing empathy19.

Neurodivergent people may ask many questions to clarify a situation, including repeatedly asking some questions to fully process information, sometimes owing to delays in auditory processing21.

With verbal communication, neurodivergent people may rely on scripts often practised many times in their head and it can be disconcerting for them if the conversation does not go as planned. They may also experience echolalia, where they may repeat phrases or quotes from films or TV shows. Some neurodivergent people may be non-speaking, this can be permanent or minimal and everything in between. Accommodations should be made for this, such as the use of pictorials22.

Socialising

Neurotypical people often enjoy social activities, particularly in groups, and may be disappointed by those who decline such events. We all have a ‘social battery’ that can become depleted. For neurodivergent people, this battery can be further depleted by using executive functioning skills, coping with sensory issues and masking. Spending time alone can be the neurodivergent way of recharging a social battery23. This could be accommodated by staggering lunch times to make break rooms less crowded, as well as reducing exposure to food smells and reducing the need to engage in small talk. People must also not be judged for opting out of social activities outside of work and not excluded socially if they choose to do activities alone.

Physical environment

The environment can have a huge impact on neurodivergent people with sensory-processing differences: strong smells, fluorescent lighting or the low-level hum of electrical equipment can overwhelm and affect the person’s ability to communicate effectively24. Although the physical environment of a pharmacy, dispensary or ward can be hard to change, the use of natural light as much as possible can help to mitigate some of this; also, allowing the use of ear plugs or defenders can help to dampen overwhelming sounds. Encouraging movement breaks outside can help to give neurodivergent team members a break from overstimulating environments.

Practical ways pharmacy teams can create an inclusive environment

Normalise the use of resources

‘Stimming’ is short for ‘self-stimulation’; examples include hand-flapping, finger-rubbing, jumping up and down, feet-rubbing, finger-clicking, humming, self-talking and hair twirling10. All people stim to some extent, but neurodivergent people stim more often, as it helps to regulate emotions, reduce anxiety and increases focus. Normalising the use of fidget resources (such as fidget spinners or fidget cubes) in the pharmacy environment and allowing people to stim openly can mean neurodivergent team members can regulate and mask less, as well as helping them focus during work.

Encourage body doubling — where another person is present when completing a task — which can be done virtually or via an app. The other person might undertake the task as well or simply be present to help support and keep the individual on track; for example, working alongside a colleague who is accurately checking prescriptions to ensure the task is done without any distraction, helping with executive function struggles25. Timers can be used by those who have time-blindness to keep them on task.

Allow mental health days

Those who are neurodivergent are more prone to mental health issues; for example, half of all autistic people experience depression26. Mental health days should be encouraged to help emotional regulation and avoid overwhelm and neurodivergent burnout16. These should be logged as sickness rather than holiday entitlement and company absence policies should be updated to accommodate this.

Provide quiet spaces

Providing a quiet space to work or to decompress, where possible, can help avoid overwhelm and reduce anxiety to help neurodivergent people regulate and help with sensory processing10.

Improve meeting protocols

Meetings can be a source of high anxiety for neurodivergent people. The demands of masking, using executive functioning skills and processing information on the spot can be high. Some of this anxiety can be removed by making cameras optional for online meetings and allowing time for people to reflect and submit ideas after the meetings in their preferred format. Provide context for any meeting: having no context can ruin the whole day for a neurodivergent person, as they may be filled with dread, thinking the worst16. This could be caused by rejection sensitivity dysphoria, which means a person can take everything personally and perceive rejection in all situations27.

Send a formal agenda prior to meetings and follow-up with minutes afterwards. This will allow time for those who struggle with auditory processing to digest the content. Applications, such as Microsoft Teams and Zoom, allow meetings to be recorded with auto-generated closed captions, which allows meetings to be watched again by those who struggle with processing delays.

Allow flexibility in the working day

Travel can be particularly stressful and tiring for neurodivergent people. The modern reliance on apps for timetables, maps and tickets, stresses owing to delays, time blindness and the sounds and smells of public transport can be an overwhelming experience. It can leave neurodivergent people tired and so time to regulate should be allowed before starting work. Be flexible and open to changing start and end times to avoid rush hours. However, having a set routine can help some neurodivergent team members, so having a regular shift pattern might make travelling more predictable and therefore less overwhelming.

In some pharmacy environments, although understandably not all, hybrid working may be possible. It allows team members to optimise their environment and the times at which they work best; this autonomy results in reduced anxiety and helps with sensory processing.

Communicate clear expectations

Make sure that all pharmacy job descriptions, rules and procedures are clear, specific and readily available. During recruitment, interview questions should be sent in advance for all interviews and two-stage questions should be avoided to ensure candidates have time to process information and give their best answer, not enduring undue pressure28. New starters should be offered the opportunity to experience the workplace before they start — this gives them a chance to test the levels of light and noise and figure out the best way to travel to work (with no time pressure).

Training

Pharmacy students and trainees should be provided with templates or samples to help them understand what is expected; submission of evidence should also not be limited to just the written medium and allowing alternative methods, such as voice notes or oral submissions, would be more inclusive to all types of learners21.

Instructions should be both verbal and written, to be more inclusive of people processing information differently. Big tasks should be broken down into smaller milestones to avoid overwhelm and help with executive functioning29.

All materials must be accessible, which means using suitable combinations of typeface, text colour and background colour. The British Dyslexia Association’s Dyslexia Style Guide is a good resource for detailed information on fonts and colours to use (or avoid)30. Accessibility requirements apply to all resources and signage within the pharmacy. Ensure emails are compatible for screen readers; for example, ensure hyperlinks are shortened and colour is not used for differentiation or emphasis31. Emails should be short and to the point. They could be structured using the ‘what, when, why’ format (what exactly do you need, when exactly do you need each bit by and why do you need each bit to be done) — this provides context, deadline and keeps emails precise16.

Conclusion

Creating an inclusive pharmacy environment comes down to having empathy and compassion, actively listening to people and being aware and accepting of neurodiversity. Provide an open and honest work environment where people feel able to disclose confidential information and ask for whatever they require without fear of negative consequences.

Everyone works differently and to ensure the best results from the team it is important to provide as many reasonable adjustments as possible to support those who may be struggling.

Caroline Murphy has two autistic ADHD children and is currently on the diagnostic pathway for autism.

- 1.Baumer N. What is neurodiversity? . Harvard Health Publishing. 2021. Accessed September 2024. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-is-neurodiversity-202111232645

- 2.Gregory E. What does it mean to be neurodivergent? . Forbes Health. February 2024. Accessed September 2024. https://www.forbes.com/health/mind/what-is-neurodivergent/

- 3.Farrant F. Celebrating neurodiversity in higher education. The British Psychological Society. 2022. Accessed September 2024. https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/celebrating-neurodiversity-higher-education

- 4.Will the doctor see me now? . ADHD Foundation. 2019. Accessed September 2024. https://www.adhdfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Will-the-doctor-see-me-now-Investigating-adult-ADHD-services-in-England-v2.0.pdf

- 5.Foster A, Crew J. NHS cannot meet autism or ADHD demand, report says. BBC News. April 2024. Accessed September 2024. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-68725973

- 6.Churchill F. Two in five disabled workers not receiving reasonable adjustments . People Management. 2022. Accessed September 2024. https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/article/1751787/two-five-disabled-workers-not-receiving-reasonable-adjustments-research-finds

- 7.GPhC registers data – Diversity data tables. General Pharmaceutical Council. September 2023. Accessed September 2024. https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fassets.pharmacyregulation.org%2Ffiles%2F2024-01%2Fgphc-all-register-diversity-data-september-2023.docx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK

- 8.Pisano GP. Neurodiversity as a Competitive Advantage. Harvard Business Review. May 2017. Accessed September 2024. https://hbr.org/2017/05/neurodiversity-as-a-competitive-advantage

- 9.Neurodiversity and abuse. Enhance the UK. December 2022. Accessed September 2024. https://enhancetheuk.org/neurodiversity-and-abuse/

- 10.Balfe A. A Different Sort of Normal. Puffin; 2021. Accessed September 2024. https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/443103/a-different-sort-of-normal-by-balfe-abigail/9780241508794

- 11.Rivera C. Creating Inclusive Workplaces for All. TEDx Talks. July 2022. Accessed September 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbXxhuraJsE

- 12.Manual of Me. Manual of Me. Accessed September 2024. https://www.manualof.me/

- 13.Dewar E. Neurodivergent Affirming Language Guide. Neurodiverse Connection. 2024. Accessed September 2024. https://ndconnection.co.uk/resources/p/nd-affirming-language-guide

- 14.Social Model vs Medical Model of disability. Disability Nottinghamshire. November 2020. Accessed September 2024. https://www.disabilitynottinghamshire.org.uk/index.php/about/social-model-vs-medical-model-of-disability/

- 15.Asperger Syndrome. National Autistic Society. June 2023. Accessed September 2024. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/what-is-autism/the-history-of-autism/asperger-syndrome

- 16.Middleton E. Unmasked: The Ultimate Guide to ADHD, Autism and Neurodivergence. Penguin Life; 2023. Accessed September 2024. https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/457703/unmasked-by-middleton-ellie/9780241651988

- 17.What is neurodiversity? . Do It Profiler. July 2020. Accessed September 2024. https://doitprofiler.com/insight/what-is-neurodiversity-for-parents/

- 18.Autism Understood. Spikey Profiles. July 2023. Accessed September 2024. https://autismunderstood.co.uk/autistic-differences/spiky-profiles/#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20primary%20things,is%20for%20most%20other%20people

- 19.Milton D. The Double Empathy Problem. National Autistic Society. 2018. Accessed September 2024. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/professional-practice/double-empathy

- 20.Sanbourne E. Help! What is Info Dumping? ADHD? Is info dumping bad? . Autistic PHD. 2023. Accessed September 2024. https://autisticphd.com/theblog/help-what-is-info-dumping

- 21.Guide to practice-based learning for neurodivergent students. Health Education England. December 2022. Accessed September 2024. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/about/how-we-work/your-area/midlands/midlands-news/guide-practice-based-learning-neurodivergent-students

- 22.El-Seoud MSA, Karkar A, Al Ja’am JM, Karam OH. A pictorial mobile-based communication application for non-verbal people with autism. 2014 International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL). Published online December 2014. doi:10.1109/icl.2014.7017828

- 23.James L. Odd Girl Out: An Autistic Woman in a Neurotypical World. Bluebird; 2017.

- 24.Grapel J, Cicchetti D, Volkmar F. Sensory features as diagnostic criteria for autism: sensory features in autism. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88(1):69-71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25745375

- 25.Pink R. Dirty Laundry: Why Adults with ADHD Are So Ashamed and What We Can Do to Help. Ten Speed Press; 2023.

- 26.Depression. National Autistic Society. January 2021. Accessed September 2024. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/mental-health/depression

- 27.Bedrossian L. Understand and address complexities of rejection sensitive dysphoria in students with ADHD. Disability Compliance for HE. 2021;26(10):4-4. doi:10.1002/dhe.31047

- 28.Maras D. What to do when interviewing an autistic person for a job. University of Bath. 2024. Accessed September 2024. https://www.bath.ac.uk/guides/what-to-do-when-interviewing-an-autistic-person-for-a-job/

- 29.ADHD Paralysis is Real: Here are 8 Ways to Overcome it. Attention Deficit Disorder Association. 2024. Accessed September 2024. https://add.org/adhd-paralysis/

- 30.Dyslexia Style Guide. British Dyslexia Association. 2023. Accessed September 2024. https://cdn.bdadyslexia.org.uk/uploads/documents/Advice/style-guide/BDA-Style-Guide-2023.pdf?v=1680514568

- 31.Chan K. Creating accessible emails. AbilityNet. June 2022. Accessed September 2024. https://abilitynet.org.uk/news-blogs/creating-accessible-emails

2 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

If only this level of recognition, understanding and acceptance had been around 20-30 years ago. Neurodivergent people were generally classed as 'shy' or 'weird' or both, and misunderstood, ignored or bullied.

Remember that 'neurodiversity' is not all one thing. Your ADHD staff member will have different needs to your autistic staff member (and needs are unique to the person - even if you have two autistic staff members, they're likely to need different things!).

You may also have people on your team who are neurodivergent but even they may not know it. This is particularly true of some demographics, such as women over the age of 40. Diagnosis of what was Asperger’s Syndrome didn’t start in schools until at least the 1990s, so anyone whose primary school days were earlier than that is likely to have been missed. Women/girls are also less likely to be diagnosed as autistic than men/boys, because the initial research was done in boys, and autism presents differently in women. Women tend to get diagnosed with a range of other mental health issues, rather than autism. It’s currently very difficult to get an NHS autism diagnosis as an adult, unless you have a supportive GP and/or the effects on your life are severe. It’s possible to go private, but that costs serious money. And, of course, either way you need to have had some sort of trigger that leads you to ask, “Might I be autistic?”

For many people, especially women, the experience of being autistic (diagnosed or not) is of constantly failing at life, seeing contemporaries whiz up the promotional ladder past us, and leaving jobs just one step ahead of things going bad – but never knowing why. We are the people who know all the technical answers, but we’re ‘not suited to a senior role’ and ‘not really a team player, if you know what I mean?’ The Buckland Report (2024) found that autistic people face the largest pay gap of all disability groups, being paid a third less than non-disabled people on average. Autistic graduates – if they can get a job at all – are most likely to be overqualified for the job they have. Some of this is due to having to cope with the physical work environment, or sometimes the demands of the job (phones… we hate phones! [Sedgewick, BMJ, 2021]) but much of it is not related to the job itself, but to the social environment. Succeeding in the neurotypical workplace demands an ability to navigate the neurotypical social dance that simply doesn’t come naturally to us. Any book on succeeding in the workplace will tell you that “It’s not what you know: it’s who you know” – and this directly disadvantages autistic people who are neurologically programmed to pursue and excel at technical competence, and be bad at social networking.

Part of the reason most (but not all) autistic people prefer to be called ‘autistic person’ rather than ‘person with autism’ is that autism-first emphasises that if we were not autistic, we would be different. While epilepsy, for example, changes a person’s experiences of life, it does not change who they are at a fundamental level: they are the same person, but *with epilepsy*. If the epilepsy were suddenly to be cured, they would remain the same person. Being autistic affects how we experience, interpret, and interact with the world in every way – it’s a fundamental part of who we *are*, not a medical condition that we *have*. If it were possible to ‘cure’ autism, the person left behind would be very different on every level.

Current research on the ‘double empathy’ problem indicates that it’s a mismatch between natural communication methods. Neurotypical people understand each other well; autistic people understand each other well. Neurotypicals and autistic people – not so much; like Americans and British people, we are divided by a common language – the words may be the same, but the thinking behind them is different. To the neurotypical, it’s polite to work up to the main topic with small talk. To the autistic person, that’s a waste of time; it’s polite to be clear and to the point about what you want. Autistic people’s body language/non-verbal may also be subtly different to neurotypical people’s, and this can also cause problems – we may be assumed to be cold, uncaring, or not listening, because we don’t show the expected neurotypical non-verbal signals.

Remember that rejection sensitivity isn't just about 'they take everything personally'. It's at least partially a result of a lifetime of doing your level best to do what people want, *and still getting rejected*. One tends to interpret an ambiguous response as negative simply because that's usually correct.

Making eye contact can be actively uncomfortable for some autistic people; it just feels too intense. It’s therefore not a matter of ‘choosing’ to avoid it (any more than you ‘choose’ to avoid sticking your hand in an open fire) – it’s an avoidance of something that can feel painful. Others may have 'monotropic' attention - we can look you in the eye, or listen to you - but not both at the same time!

Many of the things that make working life better for neurodivergent staff also help neurotypical staff. Who really enjoys being told by their manager: "I need to see you later about something..." just so you can spend the intervening time wondering what went (or you did) wrong? Does anyone get a kick from trying to figure out an SOP that skips around, misses steps, or says ‘use your judgement’ a lot? Clarity benefits everyone.

Written information can be important. For a group of people who have a reputation for knowing the tiniest details about our ‘special interest’ and being able to recall *any* of them at the hint of a hint of interest, we can have surprisingly poor short-term memory. If a list of tasks is more than two items long, the remainder may be forgotten!

There is some evidence that autistic people, in particular, process information 'bottom up' rather than 'top down'. This means we tend to look at the details first and build them into a (hopefully) coherent whole, rather than taking the generalities and then investigating specifics. We may therefore take longer to 'get the hang' of something, but when we do, our understanding may be exceptionally solid. The advantages of this in the workplace should be obvious!

There may also need to be some adjustment regarding what tasks a neurodivergent person does (“reasonable adjustments”). This is something a person with a disability is entitled to, to allow them to work effectively. However, a flexible approach to who does what may also benefit the whole team. While there are tasks that everyone needs to do (or tasks that are core to a specific role), you may have some room for manoeuvre so that everyone on the team gets to do more of what they enjoy and less of what they find stressful, boring, or unpleasant.

Don’t just think of your neurodivergent member of staff as someone with ‘needs’ requiring ‘empathy and compassion’. We’re also professionals with valuable knowledge and skills that can benefit your team.

Autistic Pharmacist. Diagnosed privately. Trigger for spending all that money: career downward spiral and fear of job loss. Pretty much business-as-usual for an autistic professional over 40!