DR JEREMY BURGESS/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the basic physiology of the eye and common causes of eye disorders;

- Identify red-flag symptoms that require urgent referral to an ophthalmologist;

- Recognise and differentiate between common eye disorders, such as blepharitis, styes and conjunctivitis;

- Provide effective patient counselling and support for managing eye disorders.

Introduction

An eye disorder refers to any condition that affects the eye or its surrounding structures, including the cornea, lens, retina, optic nerve and muscles. These disorders can be acute, developing quickly and lasting for a short period, or chronic, developing slowly and persisting over a longer duration1. Eye disorders are a frequent concern in both primary and secondary care settings, with 8.9 million vision outpatient appointments and more than 3.4 million attending hospital outpatient appointments in 20232. A poll conducted in 2024 showed that 32% of those with an eye condition would contact their GP first, 37% their high street optician and 31% visiting other healthcare settings, such as pharmacies3.

Many eye disorders that present to GPs are minor and can be treated by a pharmacist; for example, infective conjunctivitis (both viral and bacterial), of which there are 13–14 cases per 1,000 people recorded each year in England4,5. Pharmacists can play a crucial role in the early recognition and management of these conditions through initiatives such as Pharmacy First in England, which incorporates elements of the community pharmacist consultation service for minor illness consultations referrals from GPs, NHS 111 and other healthcare providers6, the Welsh common minor ailments service in Wales and NHS Pharmacy First Scotland.

Eye disorders can arise from various causes, including infections, inflammation, allergies, trauma and systemic diseases. Common contributing factors include poor eyelid hygiene, contact lens use and environmental irritants1.

This article will cover physical examination of the eye, symptoms of eye disorders and common conditions that may be encountered by pharmacists running minor ailment services, as well as introducing management of the conditions and relevant referral pathways.

Overview of physiology

The eye is a complex organ responsible for vision (see Figure 1)1. A healthy eye should be free from pain, irritation and the vision should be clear within the limits of the patient’s visual acuity (clarity of vision at a specified distance). The sclera should be white, the eye moist with clear tear film and there should be no redness or swelling of the orbit. The eyelids should be lesion free and skin healthy1.

Some eye presentations may warrant full inspection of the conjunctiva and eye lids (see Figure 2)7. But a good history is paramount in all cases to identify red flags for referral. The following should be confirmed:

- Onset of issue;

- Unilateral or bilateral;

- The symptoms experienced, specifically any pain, photophobia or visual changes;

- Presence and appearance of discharge;

- Concurrent use of contact lenses, glasses and the date of latest eye exam;

- History of foreign travel;

- History of previous eye disorders or recent eye surgery;

- Concurrent medical conditions and medications (there are ocular manifestations of systemic diseases and some medications have ocular side effects);

- Treatments tried to date and the level of response;

- Exposure to irritants;

- Occupation (may assist when reviewing potential cases of dry eye).

Red-flag and referral symptoms

There are a variety of serious eye disorders that require more specialist review. Symptoms suggestive of a serious pathology that could result in vision loss (e.g. the pain and pupil changes seen in acute glaucoma) or may be related to malignancy (e.g. vibration of vision) require urgent referral to an emergency department. Other visual changes may be better investigated by an optician who has the imaging equipment necessary to assist with prescription changes, minor eye conditions service (MECS) or fast or general referral to outpatient services for follow-up8. See the Table for detail on where to refer patients9.

For conditions that can be treated in the pharmacy, there are some referral criteria specific to each condition. See individual conditions below for more detail.

Common eye disorders

Eye disorders can be categorised as being caused by infections, inflammation, allergies, trauma and systemic diseases. The following disorders have been selected as conditions that pharmacists should be able to identify, manage (e.g. via Pharmacy First or patient self-care) or refer.

Blepharitis

A chronic disease with periodic exacerbations, blepharitis is a bilateral (affecting both eyes) condition characterised by inflammation of the eyelid margins10–12 (see Figure 3).

JANE SHEMILT, COSINE GRAPHICS/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

It is a common condition responsible for around 5% of ophthalmological presentations in primary care11. In 2009, results from a US study suggested a high population prevalence with blepharitis present in 37% and 47% of patients seen in practice by ophthalmologists and optometrists, respectively13. Blepharitis can be classified depending on the structure affected:

- Anterior: inflammation of the base of the eyelashes (skin and lash), causation can be seborrheic, bacterial (staphylococcal) or demodex (face mites);

- Posterior: meibomian gland dysfunction and or obstruction (may result in chalazion);

- Mixed: elements of anterior and posterior are present10,14.

Blepharitis can co-occur in any age group but the mean age of all types is 50 years, although staphylococcal blepharitis has a lower mean age of 42 years and predominantly affects females, owing to factors such as hormonal changes, hormonal contraceptive and eye makeup use14.

Despite the above classifications, patients will present with similar symptoms; a gritty sensation in the eyes, burning, itching and or crusting of the eyelids, recurrent styes (hordeolum) and contact lens intolerance10–12. Unilateral lid changes such as lash loss, change or architecture distortion, pearly nodule formation or non-resolving chalazion should be referred as signs of possible carcinoma10. It can be associated with, or worsen, dry eye disease, seborrheic dermatitis and acne rosacea11.

Treatment should be focused on reducing symptoms with hygiene measures, warm compresses and lid massage, as detailed in Box 110–12.

Box 1: Hygiene measures for the management of blepharitis10–12

- Eye-lid cleansing with a clot or cotton bud soaked in a cleanser (solution of sodium bicarbonate or manufactured lid cleansing product) softly moved across the lid margins, twice a day and then daily once symptoms improve;

- Warm compresses (40°C) for five minutes twice daily followed by lid massage assist in mobilising meibum;

- Dry eye may be treated with topical lubricants and any underlying condition, such as eczema or rosacea, should be treated as per standard treatment pathways;

- Patients should avoid eye makeup application on the lid margin especially eye-liner and mascara.

Although baby shampoo features in the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE)’s clinical knowledge summary on blepharitis11, there have been studies to show that it is ineffective at reducing lid inflammation with potential concern over damage to goblet cells with long-term use15.

Patients not responsive to these measures may benefit from optician review of the tear film and topical treatment with chloramphenicol ointment twice daily to the lid margin or a short course of oral antibiotics12. Patients can be directed to information from Moorfields, which includes a leaflet and video on massage techniques16,17.

Stye (hordeolum) and chalazion (meibomian cyst)

Lumps either in or along the edge of an eyelid could be either a stye or chalazion. Styes are small red sores or tender lumps that are infective in origin and are classed as:

- External: beginning at the base of eyelash, resembling a pimple, usually caused by infection of the hair follicle;

- Internal: inside the eye lid, usually caused by infection of the meibomian gland18–20.

Chalazion are lumps sized 2–8mm, they are located on the eye lid further away from the lid margin. They can reach a size at which they press on the eye and blur vision20. Chalazion usually cause little to no pain at first but can become painful as they enlarge; they are not usually infective in origin21. They are more common in adults than children and there is no difference in incidence between sexes and races, although the exact incidence is unknown18. Chalazion may develop from an internal stye, and both can be associated with blepharitis and acne rosacea18–21. Both styes and chalazion are usually unilateral with single lumps, occasionally there can be multiple chalazion22.

Both styes and chalazion can be differentiated from dacryoadenitis (infection/inflammation of the lacrimal gland, outside upper corner of each eye) and dacryocystitis (infection of the lacrimal sac, lower inner corner) from their location18. Typically, styes are self-limiting and spontaneously resolve in five to seven days18–20. Chalazion may take up to six months to resolve if the blockage of the gland hardens18–20.

Warm compresses (between 40–45°C for up to ten minutes) or hot spoon bathing multiple times a day may can be used to manage symptoms of both styes and chalazion and help drainage19,21,22. Chalazion may also benefit from eye-lid massage following application of heat to express the contents21. For external styes, plucking of the affected eye lash may assist with drainage19. Topical treatments are not routinely required unless the patient develops infective conjunctivitis (see below for treatment)18,19. Styes should be referred to the GP if they do not resolve with conservative management, or become very large or painful19. Chalazion will need GP referral if not resolved with conservative treatment but should be referred sooner if they become very painful or disrupt vision21. Chalazion that reoccur should be referred to a doctor as they may require excision and biopsy18.

Allergic conjunctivitis

Allergic conjunctivitis is an inflammation of the conjunctiva (the membrane covering the white part of the eye) caused by an allergic reaction. Common allergens include pollen, dust mites, pet dander, mould and chemicals23,24. Ocular symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis include red, itchy, and watery eyes (non-purulent), swollen eyelids and a burning sensation23. These symptoms are typically bilateral but can be unilateral if the allergen has only come into contact with one eye.

Seasonal allergic is the most common type of allergic conjunctivitis, accounting for around 90% of cases24. Non-ocular symptoms associated with pollen allergies, include sneezing and a runny nose25. Those of an atopic or allergic predisposition (around 40% of the population) may be more susceptible to the condition, with around half manifesting allergic symptoms25. Some of these patients may develop a chronic form atopic keratoconjunctivitis that can lead to visual impairment23.

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis is more common and severe in hot arid climates usually affecting boys and resolving after puberty23. Symptoms are often worse in spring and more severe. Symptoms include giant papillae on the superior tarsal conjunctiva (the inner lining of the upper eye lid), yellow–white points on the limbus (Horner’s points) or conjunctiva (Trantas dots), lower eyelid creasing (Dennie’s lines), which can assist with diagnosis23.

Identifying and avoiding the allergen can prevent symptoms23,25,26. This might involve staying indoors during high pollen seasons, using air purifiers, washing before bed or keeping windows closed. Prognosis of allergic conjunctivitis is generally good with appropriate treatment25,26. The following steps can help managing the condition:

- Applying a cold compress (five to ten minutes once or twice a day) to the eyes can help reduce swelling and itching23,25,26;

- Options for pharmacological management include topical antihistamine (e.g. Otrivine Antistin; Thea Pharmaceuticals) eye drops that also contain a vasoconstrictor agent. One drop two to three times per day can be used in those aged above 12 years old27. Improvement should be seen in a few days to a week;

- Mast cell stabiliser, sodium cromoglycate 2% one drop four times a day, is an alternative and can be used in children (check individual products for licensing information)27. These may require up to two weeks for full prophylactic benefit to be seen23;

- Side effects to topical antihistamine eye drops and sodium cromoglycate can include temporary stinging or burning. Contraindications include hypersensitivity to the medication27.

Patients may benefit from signposting to either Allergy UK or The Association of Optometrists for further information28,29. If symptoms persist, worsen, or if there is persistent blurred vision, severe symptoms, lack of response to treatment or need for frequent treatment patients should be referred to their GP in the first instance23. Those with mild papillary conjunctivitis potentially caused by contact lens wear should be referred to their optometrist for intervention23.

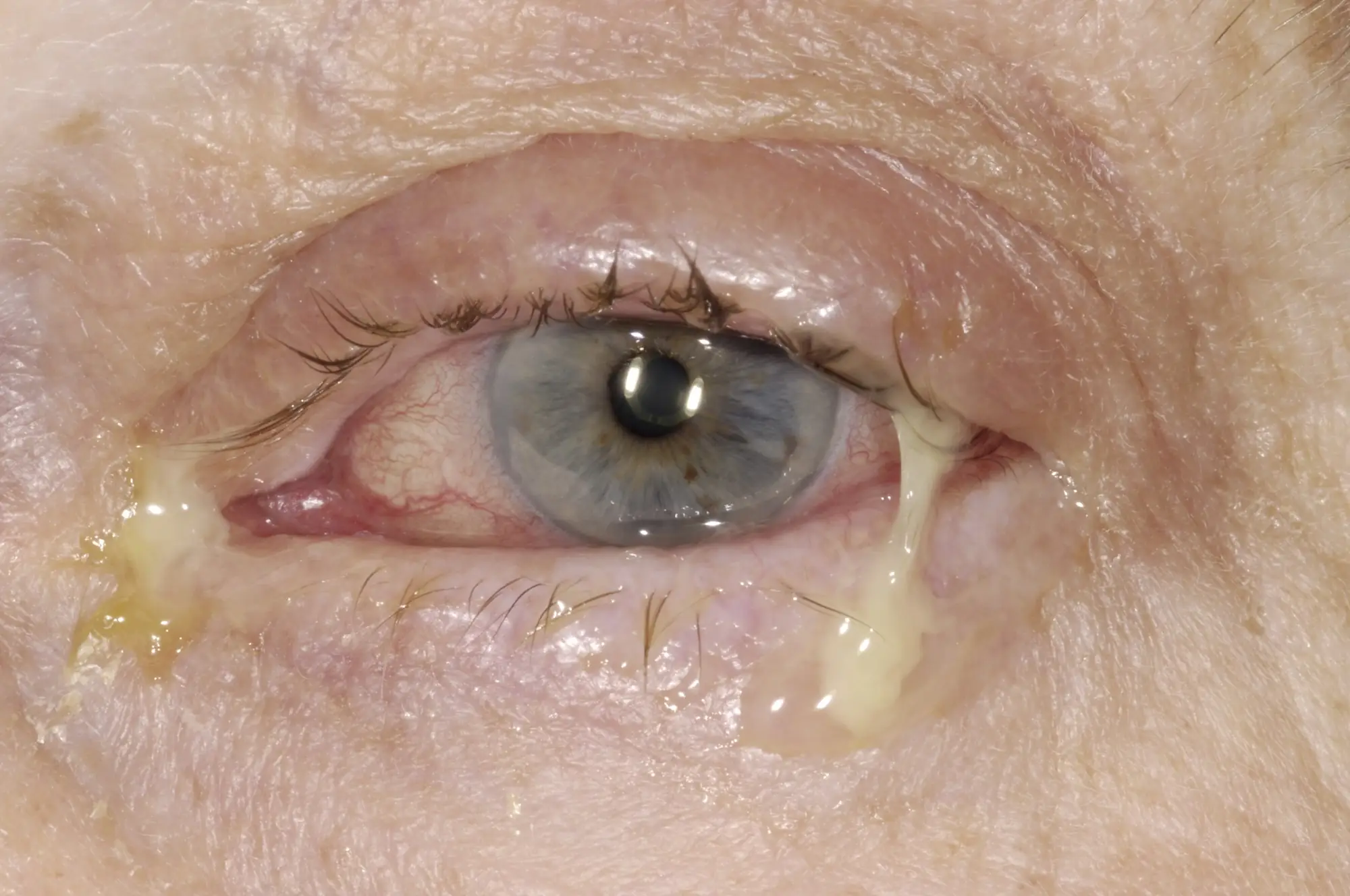

Infective conjunctivitis

In infective conjunctivitis, the inflammation of the conjunctiva is caused by a viral (accounting for 80% of cases) or bacterial pathogen, which is more common in children30. The condition is often bilateral, although one eye can become infected one or two days before the other31. In bacterial causes, eye(s) will appear bloodshot and discharge (mucus/pus) may build up (but clear on blinking) and stick to lashes or stick them together after sleep4. Patients may experience a gritty feeling in the eye but itching is unlikely4. Discharge varies depending on the cause. Viral causes tend to also have non-purulent watery discharge.

Hyperacute purulent conjunctivitis are rarer and could be caused by a sexually transmitted infection (STI), which carry a higher risk of complications and suspected cases should be referred to ophthalmology4. Similarly, newborns in the first 28 days of life may develop ophthalmia neonatorum (ON) from an STI infected birth canal and should be referred32.

In conjunctivitis, the wider orbital area should be unaffected, and if redness or swelling extends, patients should be referred for potential periorbital/orbital cellulitis4.

DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

In simple bacterial conjunctivitis, complications are uncommon. The infection is self-limiting and hygiene measures (cleansing with freshly boiled and cooled water) alone will assist in resolution. Topical antibiotics may make the patient less infectious to others; evidence suggests that there is more benefit if treatment is initiated in the first five days of presentation33. First-line treatments recommended by NICE if symptoms have not resolved within three days include:

- Chloramphenicol 0.5% drops — apply one drop two-hourly for two days, then reduce frequency depending on the severity of infection (three to four times daily is usually sufficient for less severe infection). Continue use until 48 hours after infection has cleared;

- Chloramphenicol 1% ointment — apply 1cm three to four times daily, continue use until 48 hours after infection has cleared4,27.

Formulation choice is based on patient preference, but chloramphenicol should not be prescribed to women who are pregnant or breast feeding, patients with a history of myelosuppression with prior exposure, or those with a personal or family history of aplastic anaemia or blood dyscrasias4. These patients should be referred to a GP or prescribing optometrist for an alternative treatment.

Patients wearing contact lenses should be reviewed by their optician for assessment of corneal involvement. Gram-negative organisms may be more likely in these patients, which require the use of an aminoglycoside31. Contact lens use should be avoided until all symptoms of the infection have resolved. Patients still with symptoms after 14 days of conservative management, not responding to courses of treatment, or with repeat infections should be referred to a GP. A more detailed overview of bacterial conjunctivitis can be found in ‘Bacterial conjunctivitis: diagnosis and management‘34.

Dry eye syndrome

Dry eye syndrome (DES), also known as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, is a common condition (studies show a range of 5–50% of the population) with two main causes35. Aqueous deficient dry eye occurs when the lacrimal glands do not produce enough tears, or evaporative dry eye, the more common cause which is when the tear film is unstable owing to meibomian gland dysfunction36. These two forms of gland dysfunction can overlap and co-exist36.

Patients may report bilateral eye irritation, itching, gritty sensations, redness of the conjunctiva, eye fatigue, contact lens intolerance and transient blurring of vision35–37. The sensation of eye dryness may not always be present and there can be a mucous discharge or transient watery eyes owing to reflex tearing37.

There are a wide range of causes of DES, including:

- Aging;

- Hormonal changes (especially in postmenopausal women);

- Systemic diseases (e.g. diabetes);

- Autoimmune diseases (e.g. Sjögren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis);

- Medications (e.g. antihistamines and antidepressants);

- Vitamin A deficiency blepharitis (reduces tear film production and causes surface changes to the eye);

- Contact lens use and environmental factors (like wind, smoke and dry climates)36,37.

Non-ocular symptoms can vary depending on the underlying cause. Prolonged screen time and reduced blinking (e.g. caused by Parkinson’s disease) can also contribute to DES35.

Good history taking is needed to assess for underling conditions and aggravating factors. Physical assessment is needed to check for abnormalities of structure and specifically the lids for blepharitis. Patients should always be referred to their GP for review if a serious underlying systemic condition is suspected, or there is structural abnormality37. If the symptoms are accompanied by any other symptoms suggestive of Steven-Johnson’s syndrome (e.g. fever, sore throat/mouth, widespread skin pain, rash, blisters etc) an urgent referral for urgent treatment should be made to ophthalmology37.

DES is a chronic condition, however, treatment of underlying causes as well as topical treatments can improve symptoms. Reducing screen time, taking regular breaks during computer use and ensuring proper lighting can help alleviate symptoms36. Using a humidifier to add moisture to the air can also be beneficial36. Applying a warm compress to the eyes can help to open the meibomian glands in the eyelids, improving tear quality. Patients wearing contact lens should seek advice from their optometrist regarding changes to lens type or spectacles for lens breaks37.

Mild symptoms can be managed in community pharmacy. Low viscosity drops for day time (e.g. hypromellose 0.3%) can be used one drop as required, noting that it may need frequent administration27,35. Patients can then move up in viscosity to carmellose 0.5% and carbomer 0.2% for night-time treatment, with white soft paraffin or combinations with mineral oil in ointment form added to support hydration35. There are no significant contraindications, but preservative-free formulations are preferred for frequent use. It can take up to four to six weeks for an adequate trial of a product. Patients with elements of meibomian gland dysfunction may need to switch to sodium hyaluronate or a lipid-based preparation35–37. Patients should discuss their eye dryness with their optometrist who can assess tear film and closely inspect the gland openings of the lid margins.

Patient prognosis is generally good with appropriate management; however, if symptoms persist or worsen, further medical evaluation is necessary. Both the GP and the optometrist can assist with referral to ophthalmology if a patient does not respond to management in primary care with standard prescribable lubricants. Potential complications include chronic discomfort impacting on quality of life (sleep, work driving etc.), which could lead to depression and anxiety disorders and corneal damage35–37.

Patients can be signposted to the Royal College of Ophthalmologists and Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) joint publication for patients on dry eye disease that can help them understand and manage their condition38.

Best practice points

Patients should be made aware of the following management points for their ocular condition:

- The importance of maintaining effective hygiene measures (e.g. lid cleansing);

- The importance of correct application of any treatments being used. Patients can be signposted to resources showing how to apply drops and ointments to the eye39,40;

- Clarifying the dose, frequency and duration of treatment recommended or prescribed;

- Whether contact lenses can be continued with their condition or the treatment given;

- Providing guidance on who the patient should report treatment failure to (e.g. the pharmacist, GP or ophthalmologist).

Patients should receive:

- Direction to information leaflets and information to support their condition;

- Clear descriptions of symptoms that require immediate referral (safety netting);

- Encouragement to report ocular problems to their optometrist.

Acknowledgements

Horner Transtus dots within Figure 6 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 and attributed to: Koczman J, Oetting TA: Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis: 8-year-old asthmatic male with reduced vision. EyeRounds.org. June 25, 2007; Available from: http://www.EyeRounds.org/cases/70-Vernal-Keratoconjunctivitis-Atopic-Asthma.htm.

Photographer: Stefani Karakas, CRA

- 1.James B, Bron A, Parulekar MV. Lecture Notes Ophthalmology. 12th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2016. Accessed February 2025. https://www.wiley.com/en-ca/Ophthalmology%2C+12th+Edition-p-9781119095941

- 2.Preventing illness and improving health for all: a review of the NHS Health Check programme and recommendations. Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. December 2021. Accessed February 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-health-check-programme-review/preventing-illness-and-improving-health-for-all-a-review-of-the-nhs-health-check-programme-and-recommendations

- 3.Millions of appointments for common eye conditions placing ‘unnecessary demands’ on struggling GPs, say eye experts. Association of Optometrists. June 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.aop.org.uk/our-voice/media-centre/press-releases/2024/06/12/millions-of-appointments-for-common-eye-conditions-placing-unnecessary-demands-on-struggling-gps

- 4.Conjunctivitis – infective. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. October 2022. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/conjunctivitis-infective/

- 5.Manners T. Managing eye conditions in general practice. BMJ. 1997;315(7111):816-817. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9345194

- 6.Pharmacy First service. Community Pharmacy England. November 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://cpe.org.uk/national-pharmacy-services/advanced-services/pharmacy-first-service/

- 7.Bickley LS, Szilagyi PG, Hoffman RM. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 12th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2016. Accessed February 2025. https://www.lww.co.uk/9781975210540/bates-guide-to-physical-examination-and-history-taking/

- 8.Carmichael J, Abdi S, Balaskas K, Costanza E, Blandford A. The effectiveness of interventions for optometric referrals into the hospital eye service: A review. Ophthalmic Physiologic Optic. 2023;43(6):1510-1523. doi:10.1111/opo.13219

- 9.Vision of Britain: An insight to the nation’s eye health . Optegra Eye Health. 2021. Accessed February 2025. https://www.optegra.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/VOB21.pdf

- 10.Blepharitis. BMJ Best Practice. November 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/574

- 11.Blepharitis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/blepharitis

- 12.Blepharitis (lid margin disease) . The College of Optometrists. 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/blepharitis_lidmargindisease

- 13.Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: A Survey-based Perspective on Prevalence and Treatment. The Ocular Surface. 2009;7(2):S1-S14. doi:10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70620-1

- 14.Lin A, Ahmad S, Amescua G, et al. Blepharitis Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2024;131(4):P50-P86. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.12.036

- 15.Sung J, Wang MTM, Lee SH, et al. Randomized double-masked trial of eyelid cleansing treatments for blepharitis. The Ocular Surface. 2018;16(1):77-83. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.10.005

- 16.Lid hygiene, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. YouTube. 2018. Accessed February 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oHODzr9I3MA

- 17.Blepharitis. Moorfields Eye Hospital. 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://www.moorfields.nhs.uk/mediaLocal/sz1hty1b/blepharitis.pdf

- 18.Stye and Chalazion. BMJ Best Practice. 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/214

- 19.Styes (hordeola). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/styes-hordeola

- 20.Hordeolum. The College of Optometrists. 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/hordeolum

- 21.Meibomian cyst (chalazion). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/meibomian-cyst-chalazion

- 22.Chalazion (Meibomian cyst). The College of Optometrists. 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/chalazion_meibomiancyst

- 23.Conjunctivitis – allergic . National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/conjunctivitis-allergic

- 24.Sambursky R. Acute conjunctivitis. BMJ Best Practice. November 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/68?q=Acute%20conjunctivitis&c=recentlyviewed

- 25.Conjunctivitis (seasonal & perennial allergic). College of Optometrists. 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/seasonalallergicconjunctivitis_hayfeverconjunctivi

- 26.Conjunctivitis (Acute Allergic) . College of Optometrists . 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/conjunctivitis_acuteallergic

- 27.Eye, allergy and inflammation. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Accessed February 2025. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/eye-allergy-and-inflammation/

- 28.Allergic Eye Disease. Allergy UK. July 2021. Accessed February 2025. https://www.allergyuk.org/resources/allergic-eye-disease-factsheet

- 29.Allergic conjunctivitis. Association of Optometrists. 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.aop.org.uk/advice-and-support/for-patients/eye-conditions/allergic-conjunctivitis

- 30.Høvding G. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2008;86(1):5-17. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01006.x

- 31.Conjunctivitis (bacterial). The College of Optometrists. 2018. Accessed February 2025. https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/conjunctivitis_bacterial

- 32.Ophthalmia neonatorum . College of Optometrists. 2018. Accessed February 2025. https://www.college-optometrists.org/guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/ophthalmia-neonatorum.html#:~:text=The%20definition%20of%20Ophthalmia%20Neonatorum,be%20bacterial%2C%20chlamydial%20or%20viral.

- 33.Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, van Schayck CP, McLean S, Nurmatov U. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online September 12, 2012. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001211.pub3

- 34.Bacterial conjunctivitis: diagnosis and management. Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2023. doi:10.1211/pj.2021.1.87233

- 35.Dry eye disease. BMJ Best Practice. September 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/962?q=Dry%20eye%20disease&c=suggested

- 36.Dry eye (keratoconjunctivitis sicca, KCS). College of Optometrists. July 2024. Accessed February 2025. https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/dryeye_keratoconjunctivitissicca_kcs

- 37.Dry eye disease . National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. Accessed February 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/dry-eye-disease

- 38.Understanding dry eye. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. 2017. Accessed February 2025. https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Understanding-Dry-Eye_2017.pdf

- 39.Patient information general: How to use your eye drops. Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Accessed February 2025. https://www.moorfields.nhs.uk/mediaLocal/i21m3rba/how-to-use-your-eye-drops.pdf

- 40.Patient information general: How to use your eye ointment . Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Accessed February 2025. https://uk-oa.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/How_to_use_your_eye_ointment.pdf

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You might also be interested in…

Glaucoma: an overview

Omega-3 supplements do not improve dry eye symptoms, study finds

good article covers most of the eye conditions that present in the pharmacy