Shutterstock.com

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Know how bacterial conjunctivitis is transmitted and be able to identify at-risk individuals;

- Identify the symptoms of bacterial conjunctivitis and know how to conduct an appropriate diagnostic examination;

- Manage patients with bacterial conjunctivitis and provide advice on the use of eye drops/ointment.

Conjunctivitis is generalised inflammation of the conjunctiva — the clear, thin layer of connective tissue that covers the outer globe of the eye (i.e. the bulbar) and lines the inner surface of the eyelids (i.e. the palpebral)[1]. Commonly known as ‘red eye’ or ‘pink eye’, inflammation dilates blood vessels resulting in a bloodshot appearance. Inflammation can be induced by bacterial or viral infection, allergens and chemical irritants[2]. It can occur secondary to immune mediated diseases (e.g. Stevens-Johnson syndrome) and neoplastic processes (e.g. melanoma formation) or be induced by foreign bodies[3]. The speed of onset and severity of presentation enables classification as ‘hyperacute’ (develops over 12–48 hours with profuse discharge), ‘acute’ (less than 3–4 weeks) or ‘chronic’ (4 or more weeks)[3,4]. Most cases of conjunctivitis are self-limiting and resolve within 5–7 days[4].

This article outlines how to recognise the signs and symptoms of conjunctivitis, its causes and risk factors, and the role of pharmacists in providing management advice.

Incidence and risk

Infective conjunctivitis (both viral and bacterial) is common, with 13–14 cases per 1,000 people each year in England, accounting for around 1% of all GP consultations[4,5]. Although viral conjunctivitis is the most common (accounting for 80% of cases), bacterial causes are more common in children (accounting for up to 75% of cases)[6].

Bacterial conjunctivitis can be acquired through direct contact with infected individuals or objects, such as face cloths, or from abnormal proliferation of conjunctival flora[3]. Bacteria commonly implicated include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Moraxella catarrhalis and Haemophilus influenza[2]. Gram-negative bacterial infection is more likely in contact lens users[7]. Rarer presentations are linked to sexually transmitted infections (STIs); Neisseria gonorrhoeae gives rise to a hyperacute purulent conjunctivitis and chlamydia can cause chronic conjunctivitis[4]. As conjunctivitis caused by STIs carries a higher risk of complications such as corneal perforation, ulceration and scarring, suspected STI involvement should be referred to ophthalmology for investigation[7].

Newborn babies are at a high risk of developing bacterial conjunctivitis in the first 28 days of life. Termed ophthalmia neonatorum (ON), it is acquired during transit through an infected birth canal[8]. ON caused by gonorrhoea will usually present in the first 5 days of life but may take up to 3 weeks, whereas chlamydia typically presents between the first 5–14 days of life[4].

Immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV or transplant patients who are taking certain immunosuppressive medicines, may be more at risk of developing bacterial conjunctivitis[9].

Symptoms

Bacterial conjunctivitis is often bilateral, but one eye can become infected one or two days before the other[7]. The affected eye(s) will appear bloodshot and discharge (mucus/pus) may build up and stick to lashes or stick them together after sleep[4]. Although pus can obscure vision and cause blurred vision, this should return to normal once pus is cleared from the eye by blinking.

Patients with conjunctivitis often describe a burning or gritty sensation in the eye(s). Itching is less likely in bacterial presentations because mast cells are less likely to release histamine, unlike in allergic conjunctivitis[4].

Conjunctivitis in the absence of a purulent discharge, but with increased eye watering, is more likely to be viral or allergic in nature or in response to an irritant[7]. Allergic responses may be more likely if there has been exposure to pollen or animal dander. Viral conjunctivitis is associated with viral upper respiratory tract infections[4].

Conjunctivitis in the absence of any discharge could point to dry eye syndrome (keratoconjunctivitis sicca) or blepharitis[9].

Diagnosis

A basic examination (see Box 1) and a focused ocular history is usually all that is required to diagnose bacterial conjunctivitis. Symptoms can often overlap, however, so there is not always a clear correlation to a cause[10,11]. A combination of bilateral sticking of the eyelids on waking, absence of itching and no prior conjunctivitis is suggestive of bacterial conjunctivitis[10]. Conjunctival swabs for culture and/or polymerase chain reaction are reserved for recurrent, treatment resistant, severely purulent or otherwise suspected STI origin[7].

Box 1: Physical examination of the conjunctiva

The conjunctiva should be inspected in a well-lit area or with a pen torch, with washed and disinfected hands.

The patient should be sitting comfortably before being asked to look up. The lower lid should be depressed to expose the sclera and conjunctiva lining the lower lid. The lining of the upper lid can be viewed by inverting the upper lid. The patient should be asked to look down and relax. The upper eye lid can be raised slightly by holding the eye lashes, gently pulling down and forwards. A small disposable applicator can then be placed 1cm above the lid margin. Pushing the applicator down as the lid is raised inverts the lid to expose the conjunctiva of the upper lid.

If a fuller view is needed of the front of the eye, the lids can be spread apart by a finger and thumb placed on the brow and cheek. The patient can then be asked to look up, down and from side to side.

Both the bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva should then be inspected for:

- Redness (general inflammation);

- Swelling (chemosis);

- Follicles (small yellowish elevations of lymphocytes — associated with adenovirus and chlamydia);

- Papillae (small conjunctival elevations with central vessels — associated with allergic conjunctivitis and contact lens intolerance);

- Membranes (yellow/white layer of fibrin adherent to underlying conjunctival tissue — indicates severe viral or bacterial infections).

Sources: NICE[4]; The College of Optometrists[12].

Differential diagnosis and red flags

Taking a detailed history will assist with differential diagnosis and enable serious pathologies to be discounted (see Box 2).

Box 2: Questions to ask when taking a history from a patient with suspected bacterial conjunctivitis

- When did the symptoms start?

- Which eye or eyes are affected? Was one eye affected first?

- Is there any associated pain, soreness or gritty feeling in the eyes?

- Is there any associated itching?

- Is the vision blurred or altered in any way?

- Can the discharge be described? (i.e. thick, coloured, watery)

- Have you had any cold or flu like symptoms recently?

- Do you wear contact lenses?

- Has the problem been experienced before? (if yes, when and what, if any, treatment was received)

- Has anyone else in the household been affected?

- Have any self-care measures been used?

- Do you have any long-term conditions or illnesses?

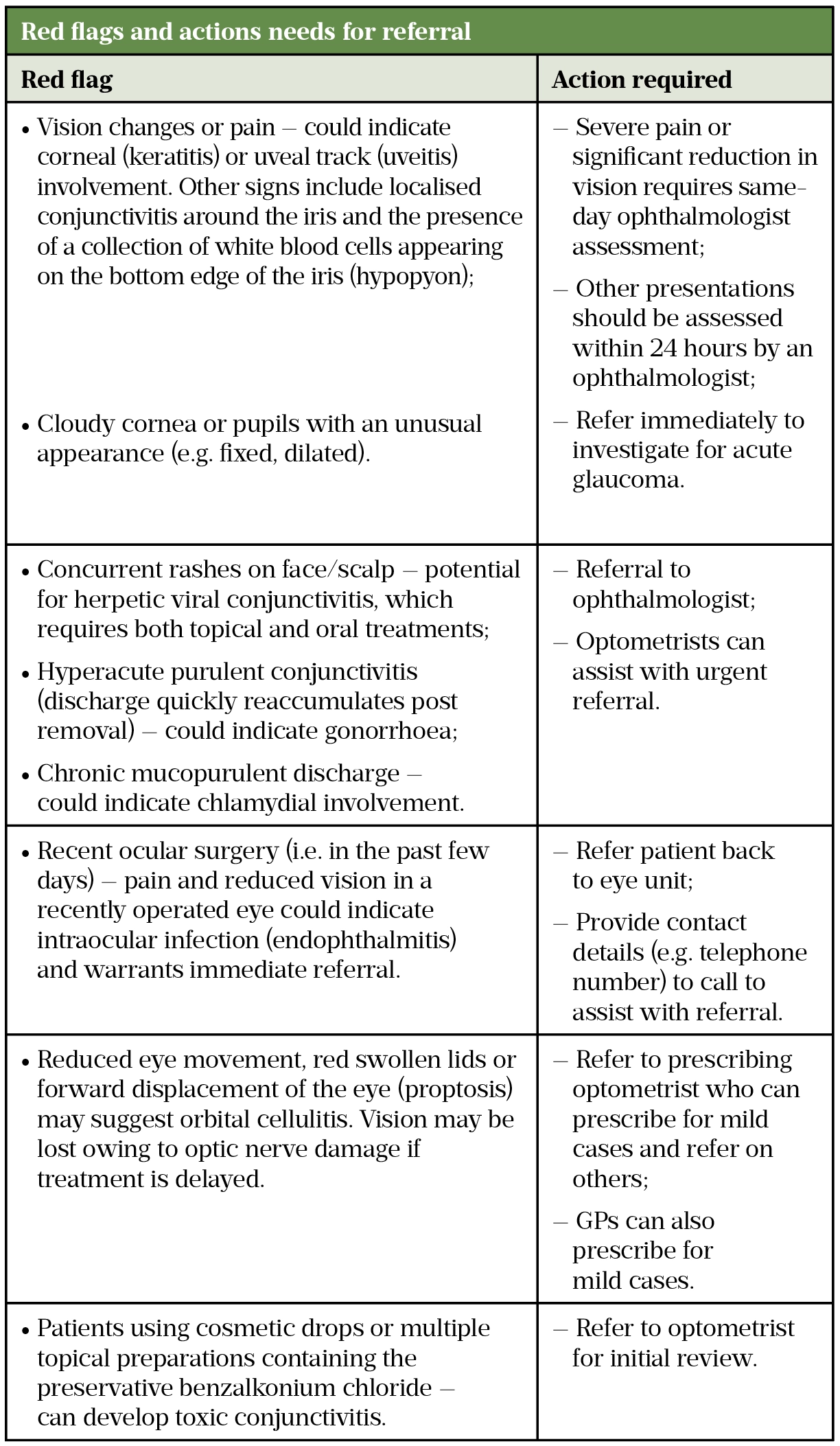

Red flags necessitating referral or additional actions are outlined in Table 1. Contact lens wearers and patients with pre-existing eye conditions, such as glaucoma, can be referred to optometrists for initial investigation. Children aged under two years, as well as pregnant or breastfeeding mothers, can be reviewed by a GP.

Optometrists are well placed to review patients with red flag symptoms and those offering an urgent eyecare service or COVID-19 urgent eyecare service (CUES service) can directly refer patients to ophthalmology[12]. Pharmacists can find participating practices via the Primary Eyecare website[13]. For an overview of the patient CUES pathway, see the College of Optometrists website.

Sources: NICE[4], NHS[14], Health Protection Agency[15], Br J Gen Pract[16], BNF[17]

Treatment and management

Pharmacological treatment is often not necessary as most cases are self-limiting and resolve within five to seven days[6]. Practical management advice can be offered to assist with comfort, such as[14]:

- Remove any pus/crusts by cleaning the eyelids with a fresh piece of cotton wool dipped in freshly boiled and cooled water. If both eyes are affected, a fresh piece should be used for each eye;

- Use a cold flannel as a cooling compress to help relieve any sensation of burning;

- Contact lenses should not be worn until the infection has resolved.

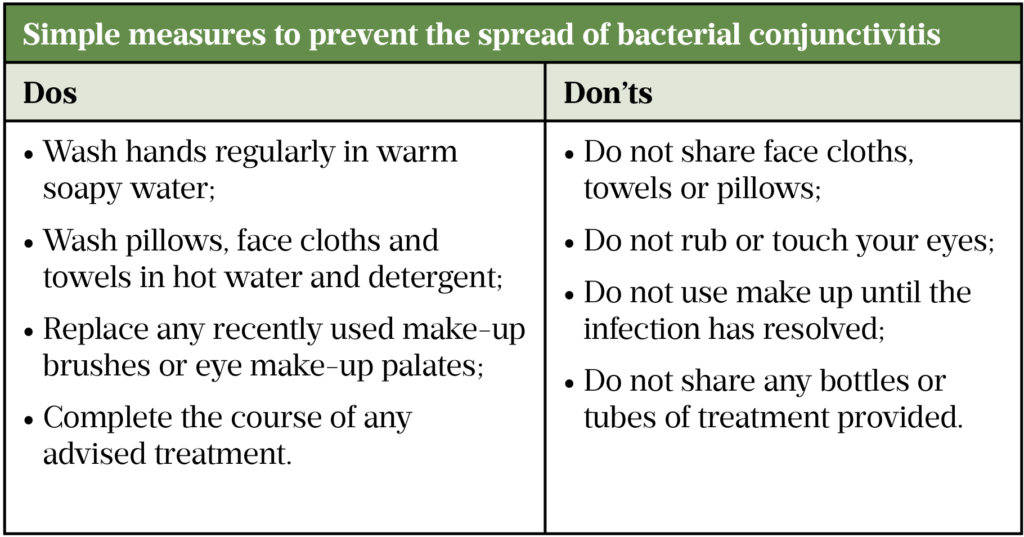

Although bacterial conjunctivitis is infectious, simple measures outlined in Table 2 below will reduce the risk of spread and patients can continue to attend work/school as normal[15]. It is important to remind patients that they should not drive or operate machinery unless vision is clear.

Sources: CDC[9], NHS[14]

Although cases are self-limiting, treatment with a topical antibiotic may speed up resolution and make the patient less infectious to others[1]. One meta-analysis found that patients with purulent discharge or a mild red eye only achieve a small benefit from treatment[16]. A Cochrane review suggested that benefit is more likely if treatment is initiated in the first five days of presentation[1].

First-line treatments recommended by National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) include[4]:

- Chloramphenicol 0.5% drops — apply 1 drop every 2 hours for 2 days, then reduce frequency depending on the severity of infection (3–4 times daily is usually sufficient for less severe infection). Continue use until 48 hours after infection has cleared;

- Chloramphenicol 1% ointment — apply 1cm 3–4 times daily for 2 days, continue to use until 48 hours after infection has cleared;

- Fusidic acid 1% eye drops — apply 1 drop twice daily. Continue use until 48 hours after infection has cleared.

Chloramphenicol has an exemption to prescription-only (POM) status, allowing pharmacists to sell the products over the counter (OTC) for use in those aged over two years[17]. Chloramphenicol is broad spectrum; it prevents bacterial reproduction via inhibition of ribosome protein synthesis[18] but has no activity against chlamydia. Patients who do not respond to treatment within 48 hours and/or who have worsening symptoms should be referred to an ophthalmologist for investigation[4,7].

Resistance rates remain stable and sensitivity high[19], however, owing to the potential for resistance, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society advises that pharmacists should judge that an OTC treatment will be beneficial and that the patient will use the product as directed[20]. The age restriction relates to potential boron exposure. Guidance from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency is that the boron exposure would be below the safety limit; however, some products may still carry this warning until manufacturers have updated their product information[21].

Contraindications for the sale of chloramphenicol include:

- Previous allergy to chloramphenicol or excipients such as borax — products vary and summary of product characteristics can be checked[22];

- Pregnancy or breastfeeding — levels of chloramphenicol are predicted to be too low in breastmilk to cause grey baby syndrome, and there have been no reported side effects in infants breastfed by mothers treated with topical chloramphenicol[23]. There has been one report of it developing in babies delivered to mothers who received chloramphenicol in the later stage of pregnancy[24]. Despite case reports suggesting a link between topical chloramphenicol and aplastic anaemia, a review found insufficient data meaning that the risk remains theoretical[25] and a population study estimates the absolute risk is very low[26]. According to the BNF, use remains reserved for essential cases by prescription should alternatives not be suitable[17];

- Those with a history or family history of blood dyscrasias, history of myelosuppression with previous chloramphenicol use or taking medication likely to suppress bone marrow, owing to rare reports of bone marrow suppression[26].

Patients wearing contact lenses should not be sold chloramphenicol unless advised by an optician, optometrist or GP[20]. The College of Optometrists advises that these patients should be treated with a topical antibiotic effective against Gram-negative organisms, such as a quinolone, or an aminogycoside[7]. If supplied with chloramphenicol, patients should be advised not to restart wearing lenses for 24 hours after completing their course of treatment. They should not reuse old contact lenses and replace any containers used for storage and cleaning[9].

Chloramphenicol is well tolerated with the most common side effects being a transient stinging/burning sensation or transient blurring of vision[14]. Systemic absorption of the drug can be reduced by employing punctual occlusion after administration (i.e. place a finger close to the corner of the eye after administration to reduce drainage into the punctum)[24,27].

The choice between drops and ointment depends on patient preference. Some feel that ointment is easier to administer as they can see what they are applying. The texture of ointment can also soothe a gritty eye. However, ointments blur vision for longer so might not be practical for all[28]. A patient may be concerned at the need to use drops every two hours initially. However, this is during waking hours only[22]. Medicines for Children have produced a factsheet that can be useful when explaining the use and administration to parents or carers[29].

Box 3: Application of eye drops and ointment[22]

- Wash hands before using the product;

- Remove the cap just before use and do not touch the nozzle of the bottle/tube with your fingers;

- Position yourself in front of a mirror;

- Gently pull down the lower eye lid with a clean finger to make a pocket in front of the eye and tilt the head back slightly;

- Hold the bottle/tube above the eye and do not allow it to touch the eye or surrounding skin;

- Squeeze 1cm of ointment / a single drop of liquid into the pocket at the front of the eye;

- Close the eye for a few minutes;

- Wipe away any extra product or liquid from the eye with a clean tissue;

- Ensure the cap is replaced and hands are washed before resuming activities.

Complications

Patients should not be unduly worried about bacterial conjunctivitis as complications are uncommon[4]. Risk of complications (e.g. keratitis and ulceration) are higher in groups that should be referred for initial treatment, such as contact lens wearers, the immunocompromised or where STIs are suspected[3,30]. Any patient who has not recovered after 14 days of conservative management or failed a course of chloramphenicol should be referred to their GP for management.

This article has been reviewed by the expert authors to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in The Pharmaceutical Journal in June 2021.

- 1Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, van Schayck CP, et al. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Published Online First: 12 September 2012. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001211.pub3

- 2Sambursky R. Acute conjunctivitis. BMJ Best Practice. 2019.https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/68?q=Acute%20conjunctivitis&c=recentlyviewed (accessed Jun 2021).

- 3Azari AA, Barney NP. Conjunctivitis. JAMA 2013;310:1721. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280318

- 4National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Conjunctivitis – infective. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/conjunctivitis-infective/ (accessed Sep 2023).

- 5Manners T. Managing eye conditions in general practice. BMJ 1997;315:816–7.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9345194

- 6Høvding G. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmologica 2008;86:5–17. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01006.x

- 7The College of Optometrists. Conjunctivitis (bacterial). The College of Optometrists. 2018.https://www.college-optometrists.org/guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/conjunctivitis-bacterial-.html (accessed Sep 2023).

- 8The College of Optometrists. Ophthalmia neonatorum. The College of Optometrists. 2018.https://www.college-optometrists.org/guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/ophthalmia-neonatorum.html#:~:text=The%20definition%20of%20Ophthalmia%20Neonatorum,be%20bacterial%2C%20chlamydial%20or%20viral (accessed Sep 2023).

- 9Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Conjunctivitis. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019.https://www.cdc.gov/conjunctivitis/about/prevention.html (accessed Jun 2021).

- 10Rietveld RP, Riet G ter, Bindels PJE, et al. Predicting bacterial cause in infectious conjunctivitis: cohort study on informativeness of combinations of signs and symptoms. BMJ 2004;329:206–10. doi:10.1136/bmj.38128.631319.ae

- 11Rietveld RP. Diagnostic impact of signs and symptoms in acute infectious conjunctivitis: systematic literature search. BMJ 2003;327:789–789. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7418.789

- 12The College of Optometrists. COVID-19 Urgent Eyecare Service (CUES) in England . The College of Optometrists. 2020.https://www.college-optometrists.org/the-college/media-hub/news-listing/nhs-england-covid-19-urgent-eyecare-service-cues.html (accessed Jun 2021).

- 13Primary Eyecare. Primary Eyecare. Primary Eyecare. https://primaryeyecare.co.uk/ (accessed Jun 2021).

- 14NHS. Conjunctivitis. NHS. 2018.https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/conjunctivitis/ (accessed Sep 2023).

- 15Health Protection Agency . Guidance on infection control in schools and other childcare settings. Health Protection Agency . 2017.https://www.publichealth.hscni.net/sites/default/files/Guidance_on_infection_control_in%20schools_poster.pdf (accessed Jun 2021).

- 16Jefferis J, Perera R, Everitt H, et al. Acute infective conjunctivitis in primary care: who needs antibiotics? An individual patient data meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e542–8. doi:10.3399/bjgp11x593811

- 17British National Formulary . Chloramphenicol. British National Formulary . 2020.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/chloramphenicol.html (accessed Sep 2023).

- 18Martindale. Chloramphenicol monograph. In: Martindale. London: : Pharmaceutical Press 2009.

- 19Silvester A, Neal T, Czanner G, et al. Adult bacterial conjunctivitis: resistance patterns over 12 years in patients attending a large primary eye care centre in the UK. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2016;1:e000006. doi:10.1136/bmjophth-2016-000006

- 20Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Chloramphenicol 0.5% w/v eye drops and 1% w/v eye ointment. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2021.https://www.rpharms.com/resources/quick-reference-guides/chloramphenicol-05w-v-eye-drops-1w-v-ointment (accessed Jun 2021).

- 21Specialist Pharmacy Service. Using chloramphenicol eye products in children under 2 years. Specialist Pharmacy Service. 2021.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/using-chloramphenicol-eye-products-in-children-under-2-years/ (accessed Sep 2023).

- 22NHS. Chloramphenicol. NHS. 2018.https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/chloramphenicol/ (accessed Sep 2023).

- 23Specialist Pharmacy Service. Chloramphenicol: is it safe in breastfeeding? Specialist Pharmacy Service. 2019.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/QA263-5_ChloramphenicolBF_FINAL.pdf (accessed Jun 2021).

- 24Briggs G, Freeman R. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation. 10th ed. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health 2015.

- 25Fraunfelder FT, Morgan RL, Yunis AA. Blood Dyscrasias and Topical Ophthalmic Chloramphenicol. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1993;115:812–3. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73653-0

- 26Laporte J, Vidal X, Ballarín E, et al. Possible association between ocular chloramphenicol and aplastic anaemia—the absolute risk is very low. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1998;46:181–4. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00773.x

- 27Lewis N. Case 2: Chronic open-angle glaucoma. Pharmaceutical Press 2015.

- 28Specialist Pharmacy Service. Chloramphenicol. Specialist Pharmacy Service. 2020.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/medicines/chloramphenicol/ (accessed Jun 2021).

- 29Medicines for Children. Chloramphenicol for eye infections. Medicines for Children. 2012.https://www.medicinesforchildren.org.uk/chloramphenicol-eye-infections-0 (accessed Jun 2021).

- 30Forister JFY, Forister EF, Yeung KK, et al. Prevalence of Contact Lens-Related Complications: UCLA Contact Lens Study. Eye & Contact Lens: Science & Clinical Practice 2009;35:176–80. doi:10.1097/icl.0b013e3181a7bda1