CID - ISM / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the presentation of and how to diagnose keloid scars;

- Identify patients who may require referral;

- Understand appropriate treatment and management options.

A keloid scar, or keloid, is a dermal fibroproliferative growth caused by pathologic wound healing following injury to the skin (e.g. ear piercings, burns, acne scarring and surgical wounds; see Figure 1)[1].

Collagen plays an important part in wound healing, attracting cells (such as fibroblasts and keratinocytes) to the wound, encouraging debridement, angiogenesis and re-epithelialisation[1]. In normal scarring, the collagen breaks down once the wound has healed, but this fails to happen during the formation of a keloid scar. Excessive fibroblast proliferation and the deposition of matrix and collagen fibres causes the scar to expand from its original boundaries and continue to grow even after the wound has healed[1]. Endocrine factors and local tissue components — especially wound tension or infection — are known to be involved in their formation[1].

DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

The incidence of keloids is higher in skin of colour and if one or both parents have a history of them, suggesting that genetic factors play a role in their development (see Box)[1,2]. Younger people aged 10–30 years are also more likely to develop them [3]. Women are more likely to develop keloids but this may, in part, be reflected by the number of earlobe keloids secondary to ear piercing, which are more common in women[4].

Pharmacists should be able to recognise the pathology of keloids and confidently diagnose and appropriately refer patients to general practice for optimal management. The rest of this article will outline this information.

Box: Risk factors

Risk factors associated with keloid formation include:

- Having darker skin tone;

- Being of Asian or Latino descent;

- Pregnancy;

- Aged under 30 years.

Diagnosis

Keloid scars are usually shiny, hairless, raised above the surrounding skin, hard and rubbery. They can look red or purple at first, before becoming brown or pale. They can last for years and sometimes do not form until months or years after the initial injury (see Figures 2 and 3)[3].

Keloids can occur anywhere on the body but are most common after skin injury on the upper chest, shoulders, chin, neck and earlobes[5]. Keloid formation is also common after surgery and burns and acne[5].

Keloids can cause pain and functional disability (i.e. restricting movement if growth is on joints) and their appearance can cause psychosocial distress. Scars on the face can be especially distressing and can therefore negatively affect a patient’s quality of life[6].

Differential diagnoses

Obtaining a detailed history can help to differentiate between different types of lesions and conditions with similar presentations (as outlined below).

Hypertrophic scars

All trauma that involves the dermis will heal with a scar; however, in some individuals, the scar is much larger and thicker than normal, resulting in a hypertrophic scar[7]. In contrast to keloids, hypertrophic scars are always preceded by trauma and confined to the margin of the wound[7]. Hypertrophic scars appear immediately after trauma and show a tendency to gradually regress, whereas keloids can appear soon after injury or be delayed in appearance (developing months later) and are thought to very rarely spontaneously resolve[7,8]. Figure 4 shows the differences between scar types[9].

A scar showing signs of infection — such as swelling, bleeding, tenderness, warmth to the touch or presence of pus — should be referred urgently because a course of antibiotics is probably required. Additionally, if the patient is experiencing pain and discomfort, the patient should be referred to their GP for further assessment.

Acne keloidalis nuchae

Also referred to as folliculitis keloidalis, acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic inflammatory condition in which painful pustules and keloid-like papules and plaques commonly occur at the nape of the neck[10]. This condition typically presents in young males with Fitzpatrick skin phenotypes V and VI (i.e. brown, dark brown or black skin)[11]. Women are rarely affected unless they shave their hair at the nape of the neck. Figure 5 shows typical acne keloidalis nuchae[12].

The patient should be referred to their GP for further assessment and treatment if they have painful inflammatory lesions that are localised primarily to the nape of the neck.

Foreign body reaction

Exogenous material in the dermis or subcutis is referred to as a ‘foreign body’ and is recognised by the body as ‘nonself’[13,14]. Examples include piercings, synthetic fillers, tattoo inks and wood splinters. A foreign body lesion can occur at any age and begins with acute inflammation at the site of entry of the foreign material. However, after a period of weeks, months or even years, a chronic inflammatory reaction can reoccur, presenting as a red or red-brown inflamed papule, plaque, or nodule.

Taking a full history and looking at the appearance of lesions can aid diagnosis. However, diagnosis can be confirmed via a biopsy. Patients should be referred to their GP and a further referral will be made to a dermatologist[15].

Treatment

Keloids can be difficult to treat but there are several options that can help minimise the discomfort and disfigurement. No treatment is completely effective, but the options outlined below have been shown to be beneficial.

Intralesional steroids

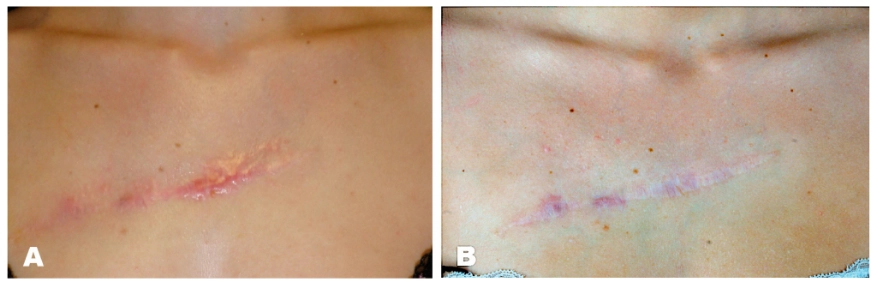

The most common and effective treatment for keloid scars is intralesional steroids (triamcinolone). Injections have been shown to be more than 80% effective in reducing and resolving keloid scars (see Figure 6)[16,17].

Adverse effects of intralesional steroids include subcutaneous atrophy (loss of fatty tissue leading to a sunken look of the skin), telangiectasis (broken capillaries) and pigment changes. These occur in around half of all patients treated with triamcinolone but frequently resolve without further intervention[16]. The systemic effects of steroids (Cushing’s syndrome) generally do not occur with intralesional triamcinolone treatment, but rare cases have been reported[16].

Triamcinolone inhibits the proliferation of normal and keloid fibroblasts, inhibits collagen synthesis, increases collagenase production and reduces levels of collagenase inhibitors. Around half of all patients experience adverse effects, including subcutaneous atrophy, telangiectasia (spider veins – small red or purple clusters on the skin) and pigment changes, but these frequently resolve without further intervention[16].

Surgery

Surgical removal of keloids alone has consistently shown poor results, with recurrence of keloids at a rate of 40–100%([16]. Surgical removal is thought to stimulate additional collagen synthesis, resulting in rapid regrowth and often a larger keloid[16]. Surgery should be a last resort when other treatments have not been successful. Recurrence can be reduced with the use of ‘triple therapy’, which involves surgery with the use of compression dressings and intralesional steroid injections following surgery[5,18]. Figure 7 shows an example of surgical removal[16].

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery involves rapid, repeated cooling and rewarming of tissue, leading to cell death and tissue sloughing. The efficacy of cryosurgery on keloids has been reported as 50–85%, with moderate flattening and symptomatic relief[16]. Unlike surgical excision, cryosurgery also has a direct beneficial effect on the keloidal collagen, resulting in improved collagen-bundle organisation. Cryosurgery is often used on smaller keloids[18].

Cryotherapy can cause hypopigmentation or depigmentation that can be prominent and long-lasting in darker skin types. Patients should be made aware of this possibility[16]. Permanent alopecia can also occur following cryotherapy, owing to the destruction of the hair follicles[16]. Raynaud’s and cold urticaria are contraindications[19].

Silicone gel

Silicone gel is effective in the management of keloids and is thought to work by increasing the temperature and hydration, causing the scar to soften and flatten[19]. This can be a first-line treatment alone or as an effective adjunct to surgical keloid excision to help minimise the recurrence of keloids (as mentioned above, recurrence rates are higher with surgery alone). Silicone gel, either as a topical gel or impregnated elastic sheet, requires covering the entire scar for at least 12 hours a day for up to 6 months. Treatment adherence may be an issue. Common adverse effects include application-site irritation, but this resolves upon removal of the gel[5,16].

Compression therapy

Pressure therapy following excision is simple and effective with minimal adverse effects, but its practical use is limited to earlobes. The mechanism of pressure therapy has not been determined. Compression earrings should be worn 24 hours a day after excision; however, treatment adherence can be an issue[5,16].

Complications

Keloid scars can cause prolonged pain and pruritus, as well as being cosmetically disfiguring, which can cause emotional and psychological distress to patients. Depending on location and size, they can restrict movement. There is a risk of recurrence of keloids with any therapy, with the highest recurrence rate following surgical excision. Steroid use carries a risk of telangiectasias, atrophy and changes in pigmentation around the treatment site.

Important counselling advice for patients

Although they cannot be completely prevented, pharmacists can provide the following advice to patients prone to the development, or at risk of keloid scars:

- Avoid deliberate cuts or breaks in the skin such as tattoos and piercings[3];

- Treating inflammatory acne will also minimise the risk of scarring[3]. This can be done effectively with a combination of oral antibiotics and topical treatments, such as retinoids and benzoyl peroxide[20];

- If possible, avoid minor surgical procedures in areas that are prone to keloids[3].

When treating keloids, it is important to adhere to the treatment to give it the best chance of success[5,16]. Pharmacists should assist by determining which treatment are most suited and will easily fit in to daily life. Pharmacists may wish to follow up with their patients to determine adherence and discuss alternative options if adherence is proving difficult.

If patients are experiencing pain, discomfort or psychological distress from their keloid scars, they should be referred to their GP to discuss suitable treatment options. An over-the-counter option can be suggested, such as scar treatment silicone gel.

- 1Nakashima M, Chung S, Takahashi A, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies four susceptibility loci for keloid in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2010;42:768–71. doi:10.1038/ng.645

- 2Cafasso J. Treatments for Hypertrophic Scars. Healthline. 2017.https://www.healthline.com/health/hypertrophic-scar-treatment (accessed Apr 2022).

- 3Keloid scars. NHS. 2019.https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/healthy-body/keloid-scars (accessed Apr 2022).

- 4Kelly AP. Medical and surgical therapies for keloids. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:212–8. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04022.x

- 5Keloids. British Association of Dermatologists. 2018.https://www.bad.org.uk/for-the-public/patient-information-leaflets/ (accessed Apr 2022).

- 6Lu W, Chu H, Zheng X. Effects on quality of life and psychosocial wellbeing in Chinese patients with keloids. Am J Transl Res 2021;15.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33841685/

- 7Carswell L, Borger J. Hypertrophic Scarring Keloids. National Library of Medicine. 2020.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537058/ (accessed Apr 2022).

- 8Oakley A. Keloid and hypertrophic scar. DermNet NZ. 1997.https://dermnetnz.org/topics/keloid-and-hypertrophic-scar (accessed Apr 2022).

- 9Limandjaja GC, Niessen FB, Scheper RJ, et al. Hypertrophic scars and keloids: Overview of the evidence and practical guide for differentiating between these abnormal scars. Exp Dermatol. 2020;30:146–61. doi:10.1111/exd.14121

- 10Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. CCID. 2016;Volume 9:483–9. doi:10.2147/ccid.s99225

- 11Recognising common skin conditions in people of colour. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2021. doi:10.1211/pj.2021.1.113627

- 12Al Aboud DM, Badri T. Acne Keloidalis Nuchae. National Library of Medicine. 2021.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459135/ (accessed Apr 2022).

- 13Lee JM, Kim YJ. Foreign Body Granulomas after the Use of Dermal Fillers: Pathophysiology, Clinical Appearance, Histologic Features, and Treatment. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42:232. doi:10.5999/aps.2015.42.2.232

- 14Rupert J, Honeycutt J, Odom M. Foreign Bodies in the Skin: Evaluation and Management. Am Fam Physician 2020;101:740–7.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32538598

- 15Ogawa R, Akita S, Akaishi S, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars—Japan Scar Workshop Consensus Document 2018. Burns & Trauma. 2019;7. doi:10.1186/s41038-019-0175-y

- 16Al-Attar A, Mess S, Thomassen JM, et al. Keloid Pathogenesis and Treatment. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;117:286–300. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000195073.73580.46

- 17Dastagir K, Obed D, Bucher F, et al. Non-Invasive and Surgical Modalities for Scar Management: A Clinical Algorithm. JPM. 2021;11:1259. doi:10.3390/jpm11121259

- 18Juckett G, Hartman-Adams H. Management of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Am Fam Physician 2009;80:253–60.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19621835

- 19Cryotherapy. National Library of Medicine. 2018.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482319/ (accessed Apr 2022).

- 20Acne vulgaris: management. NICE guideline [NG198]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng198 (accessed Apr 2022).

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Any thoughts in light of discontinuation of UK triamcinolone injection products?