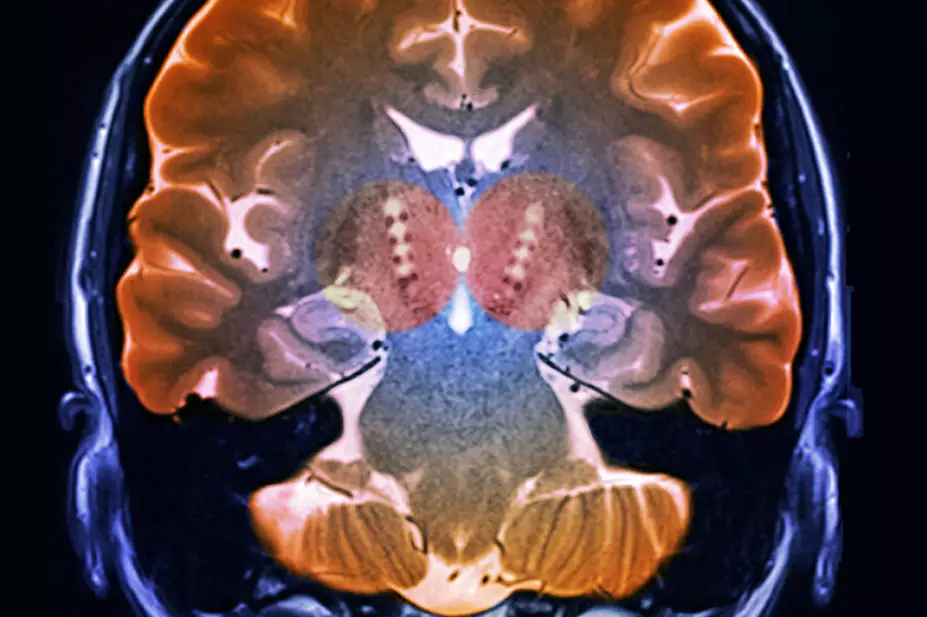

ZEPHYR / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Explain the aetiology and signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease;

- Understand the available management options for motor and non-motor symptoms;

- List simple interventions pharmacists can perform to improve the quality of life of people with Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder, first described in 1817 in ‘an essay on the shaking palsy’ by surgeon James Parkinson. It is caused by the loss of dopamine-containing cells in the substantia nigra. Dopamine is critical to movement; therefore, its loss leads to motor symptoms affecting movement[1,2]. However, as understanding of PD increases, it is becoming clear that PD is not just a disorder of movement, but is associated with significant non-motor symptoms too[3,4].

In the UK, 1 in 37 people are diagnosed with PD in their lifetime. Approximately 93% of people with PD in the UK are aged 50–89 years[5]. The charity Parkinson’s UK estimates that there are 145,000 people with PD in the UK and projects this will rise to 172,000 by 2030[5]. To put that into perspective for healthcare providers, a GP with a list size of 1,500 patients will see one new case of PD every 3.3 years[6].

The underlying cause of idiopathic PD (the most common type of PD) is unknown, but risk factors have been identified (see Box 1).

Box 1: Risk factors for Parkinson’s disease

- Increasing age

- Male gender

- Head trauma

- Common genetic mutations (e.g. LRRK2, GBA, SNCA)

- Environmental toxin (e.g. 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine [MPTP]) exposure[5–7]

This article aims to provide a brief overview of PD, including symptoms and pharmacological therapy. It also aims to provide practical tips on the management of medication for people with PD.

Symptoms

In PD, the focus has traditionally been on motor symptoms caused by the loss of dopamine. Motor symptoms of PD are not usually clinically apparent until at least 50% of dopaminergic cell activity has been lost[6].

The classical motor symptoms of PD are explained in Table 1[2]. Other motor symptoms include dystonia, freezing and postural instability[5–7].

Non-motor symptoms are being increasingly recognised and, in many cases, have a bigger impact on quality of life than motor symptoms[3]. Non-motor symptoms affect many systems in the body. Box 2 lists some examples.

Box 2: Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease

- Constipation;

- Sleep disorders (e.g. restless leg syndrome, rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder, excessive daytime sleepiness, insomnia);

- Autonomic disturbance (e.g. orthostatic hypotension, urinary urgency, erectile dysfunction and sweating);

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms (e.g. mild memory and thinking difficulties, anxiety, dementia, depression, hallucinations, sleep disorders, delusions);

- Speech and swallow impairments (e.g. impaired swallowing, drooling and voice/speech disorder);

- Eye problems (e.g. excessive tearing);

- Pain (e.g. musculoskeletal pain, Parkinson’s-related chronic central or visceral pain);

- Fatigue;

- Olfactory disturbance[8].

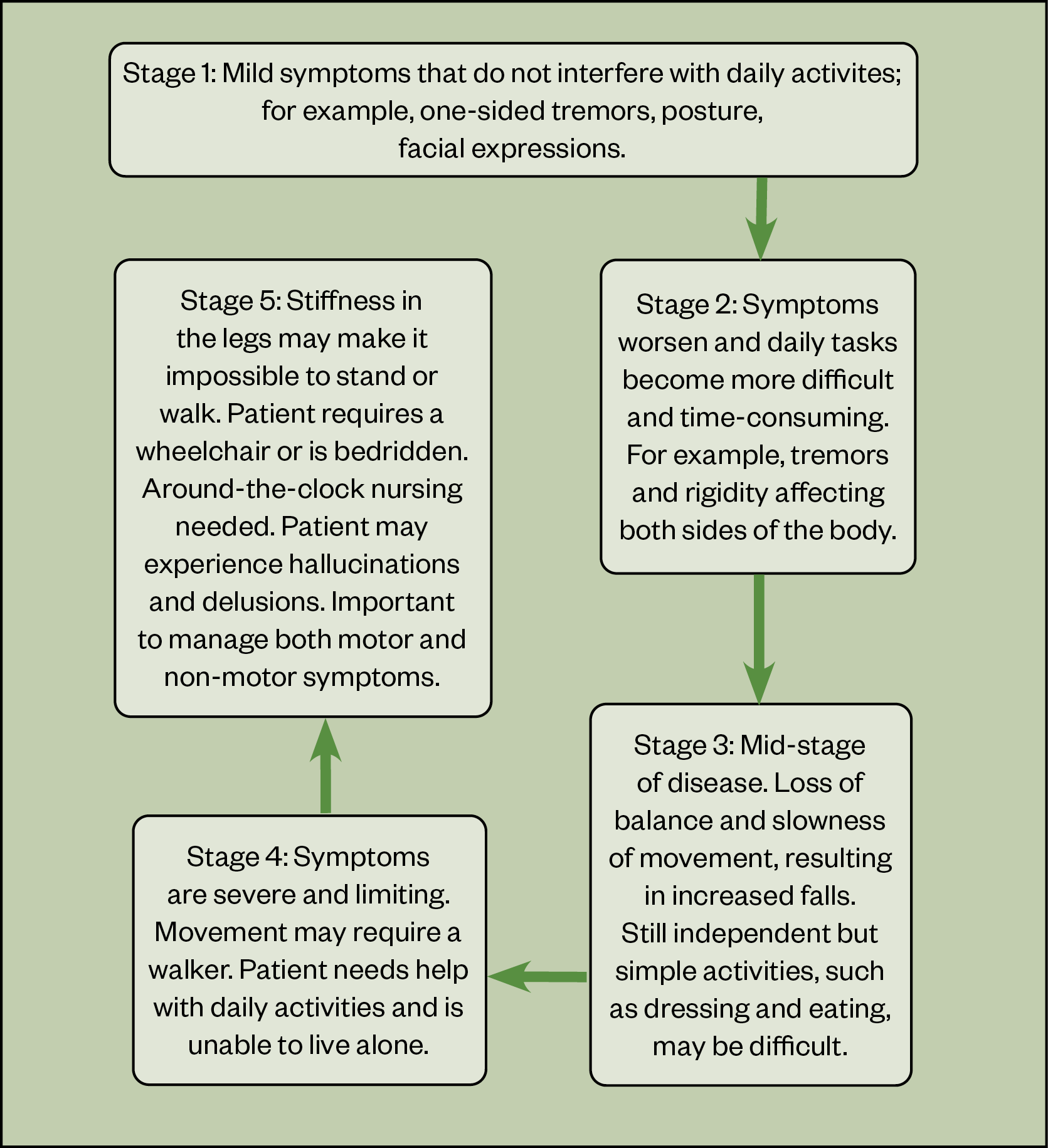

There are many potential symptoms of PD and no two experiences of PD will be the same. Each person will experience a different combination of symptoms and an individual rate of progression of those symptoms[8]. Traditional thinking labels PD as a movement disorder and, often, the most obvious symptoms are indeed motor related (see Figure 1). However, studies confirm that non-motor symptoms often have a bigger impact on quality of life than motor symptoms[3].

Many tools and scales are available to assess both disease progression and the impact of symptoms on quality of life. These include the Movement Disorder Society sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), which assesses the course of disease, and the non-motor symptoms questionnaire, both specific and validated to PD[9,10]. Disease progression is often described in stages (see Figure)[8].

Diagnosis

PD develops gradually; it can be months or years before symptoms become apparent enough for someone to seek medical advice. Evidence of the prodromal phase lasting up to 20 years before diagnosis is emerging, with symptoms of hyposmia, reduced sense of smell, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder, depression and anxiety reported before the motor symptoms appear[11]. These non-motor symptoms may be the result of compensatory activity of other neurotransmitters (e.g. serotonin)[12].

The umbrella term ‘Parkinsonism’ is used to describe symptoms or signs found in PD that can also be found in other conditions[7]. Diseases that exhibit Parkinsonian symptoms but are not idiopathic PD include multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, vascular PD and drug-induced Parkinsonism[8]. Medications associated with drug-induced Parkinsonism — for example, older generation antipsychotics, antihistamines such as cinnarizine, methyldopa and antiemetics, such as metoclopramide — typically inhibit the actions of dopamine in the brain[13].

Diagnosis of PD is based on clinical presentation, as there is no reliable diagnostic test. This can lead to uncertainty in diagnosis, which formed the basis of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendation that diagnosis should be made by a neurology specialist[14]. Misclassification in early disease is reported to occur in 15% of cases diagnosed by a specialist; this figure is higher in non-experts[14].

The Movement Disorder Society (MDS) criteria for diagnosis are based on presentation of motor symptoms: bradykinesia plus rest tremor and/or rigidity. In addition, for a diagnosis of PD, exclusion criteria must be absent and there must be no red flags. While not essential criteria, the MDS now recommends that non-motor symptoms are taken into consideration when considering a diagnosis of PD[15].

Scans to assist diagnosis, although not definitive, are available (Table 2). A dopamine transporter scan (DaTSCAN) is widely used as an additional tool in clinical practice, while other types of single-photon emission computerised tomography (SPECT) scans are reserved for clinical trials[16]. DaTSCAN cannot differentiate idiopathic PD from other types of Parkinsonian syndrome, such as multiple system atrophy or progressive supranuclear palsy.

Parkinson’s disease services

In the UK, people with PD usually have a named consultant specialist who they may see once per year, where available, and a PD specialist nurse who is often pivotal in co-ordinating care and providing support. Not all patients have a specialist nurse, and even those who do may not be able to access support between routine appointments[17]. In some areas, outreach and community teams are available and care is well integrated, but the recent Parkinson’s UK audit showed that this is not the case everywhere[17]. Given the range of symptoms that patients can experience, optimal management of PD involves many health and social care professionals to work together effectively[13].

Table 3 details the roles and responsibilities of the wider multidisciplinary team[13,14,18]. It is essential for pharmacists to find out what services are available in their areas and how to access and refer patients to these services.

Management of Parkinson’s disease

Overall treatment is specific to the patient and the symptoms they experience. Symptoms can be variable from day to day or even hour to hour; therefore, it is important that patients have a good understanding of their treatment, disease, coping mechanism, support system and regular reviews. Life expectancy can be normal; however, more advanced symptoms can lead to increased disability and poor health, which may make someone more vulnerable to complications (e.g. infection)[8,19].

Pharmacological management of motor symptoms

The Parkinson’s UK audit identified medicines management as a main area for improvement in PD services, as a third of patients feel that they are not given enough information when starting a new medicine (17). People with PD have a higher rate of emergency hospital admission than the general population and are also twice as likely to stay in hospital; studies suggest that medicines management plays a part in extended lengths of stay[20].

The inpatient management of PD was previously covered in the learning article ‘Considerations for the inpatient management of Parkinson’s disease’.

There is no cure for PD and no drug treatments have been proven to impact disease progression. Management is therefore symptomatic. Treatments to manage motor symptoms work by increasing dopaminergic activity[8]. This is broadly achieved by three mechanisms:

- Administration of dopamine precursor (e.g. levodopa preparations such as co-careldopa);

- Activation of dopamine receptors using dopamine agonists (e.g. ropinirole);

- Enzyme inhibition to prevent the breakdown of dopamine (e.g. monoamine oxidase B inhibitors [MAO-B] and catechol-O-methyl transferase [COMT] inhibitors).

There is growing evidence to support a strategy of early treatment for people with PD, rather than waiting for symptom progression[20]. The choice of first-line treatment has been long debated and there are no absolute rules on which medication should be initiated first. NICE recommends that people with PD who have symptoms affecting their daily life are offered a levodopa preparation as first-line treatment. The PD MED Study supports this, showing that levodopa has advantages in the management of motor symptoms when compared with dopamine agonists and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. All other people with PD should be offered a levodopa preparation, dopamine agonist or MAO-B inhibitor[14]. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in benefits of dopamine agonists over monoamine oxidase inhibitors when chosen as initial therapy[21].

Anticholinergics, such as benztropine and trihexyphenidyl, are not routinely prescribed in idiopathic PD but may be introduced for the management of tremor when dopaminergic medications are not effective. However, they should be avoided in the elderly population as they can cause hallucinations and confusion[22].

Levodopa therapy

Levodopa treatment is gold standard and can be prescribed for all stages of PD[21]. It is always given with concomitant dopa-decarboxylase inhibitors (carbidopa or benserazide) to enable levodopa to cross the blood–brain barrier and prevent break down of levodopa to dopamine in the gut (reducing side effects, such as nausea and vomiting)[23]. Long-term use of levodopa can result in the patient experiencing dyskinesia and motor fluctuations (where the patient experiences ‘off-time’ periods, as the drug wears off and symptoms re-emerge)[8,24]. The short half-life and reducing duration of action make it important that patients get their medication on time every time. Strategies to help manage fluctuations in treatment effect are listed in Table 4. The individual nature of PD means ‘on time’ is not the same time or frequency for all patients. Late and missed doses contribute to risks of severe complications (e.g. pneumonia and falls).

Catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors

The inhibition of COMT prevents peripheral breakdown of levodopa, allowing more levodopa to reach the brain and prolonging the effect of levodopa dosing. As a result, concurrent levodopa doses need to be reviewed and possibly reduced by up to 30%[24]. The COMT inhibitor entacapone is usually taken with each levodopa dose and is available alone or as a combination product with levodopa and carbidopa (which can be helpful in reducing tablet burden)[25]. An alternative is opicapone, which is taken just once per day[26].

Glutamate antagonists

Glutamate antagonists, such as amantadine, are generally used to reduce dyskinesia caused by levodopa therapy. They can be used in all stages of PD, but are often prescribed when alternative strategies have not effectively managed motor complications[24].

Dopamine agonists

Dopamine agonists stimulate dopamine receptors and require no modification. Preparations include modified- and immediate-release tablets (e.g. pramipexole and ropinirole), patches (rotigotine) and injections (apomorphine).

There are two subclasses of dopamine agonists — ergoline and non-ergoline agonists — which both target dopamine D2-type receptors[23]. Ergoline dopamine agonists, which include bromocriptine, pergolide, lisuride and cabergoline, are no longer routinely used in the treatment of PD because of adverse fibrotic reactions[27]. Non-ergoline dopamine agonists remain widely used and include ropinirole and pramipexole. Dopamine agonists may be less likely to cause dyskinesia and motor fluctuations than levodopa[21]. Rotigotine is delivered transdermally via a patch, which can be particularly useful where patients have a high tablet burden or where patients have swallowing difficulties. Apomorphine is considered in advanced PD (see below).

Some side effects of dopaminergic therapy are more common with dopamine agonists than other therapies. Impulse-control disorders are one such symptom: studies show more than 50% of patients experience them on therapy, with incidence increasing with higher doses and longer exposure[28]. However, this can occur at any stage of disease progression[28]. It is therefore important that patients and their immediate support system are provided with verbal and written support on this risk and are able to report any concerns[29]. Owing to the high incidence rate, it is prudent to document that this consultation has taken place and also when any modification in treatment occurs. Typical presentations include addictive gambling, hypersexuality, binge eating and obsessive shopping. Somnolence, day-time sleepiness and hallucinations are also associated with PD and dopaminergic therapy, and are more common with dopamine-agonist therapy[8]. Again, incidence increases with higher doses[8].

Monoamine oxidase B inhibitors

MAO-B inhibitors increase the length of time dopamine is active in the brain by preventing it from being broken down. Rasagiline and selegiline can be prescribed in early disease as monotherapy, and can be used in combination with other treatments later in the disease course[14]. Concomitant antidepressants are cautioned with MAO-B inhibitors because of the risk of serotonin syndrome. Hypertension is common when high-dose selegiline is taken with tyramine-rich foods[30].

General regimen complications and challenges

The progressive nature of PD inevitably means dosage increases and the need for new medications and regimen adjustments on a regular basis. This often results in people receiving combination therapy; for example, a levodopa preparation and an adjuvant agent, with increasing frequency of dosing and an increasing number of products and/or formulations making up those doses. Multiple formulation options and combinations can make medication regimens appear very complicated. For co-beneldopa therapy alone, there are six distinct products with three strengths and three formulations — even without considering generic and branded products[23].

This can be confusing for healthcare professionals, people with PD and their carers. Failure to take medications on time (either intentionally or accidentally) can lead to serious complications — for instance, deteriorating swallow and subsequent aspiration pneumonia (the leading cause of death in PD). Parkinson’s UK has a long running ‘Get It On Time’, and more recently ‘Time Critical Medication’, campaign with many initiatives to help support medicines adherence[31].

It is important that all pharmacy professionals are aware and share the importance of medication in PD. They can also play a vital role in helping to deliver strategies to reduce the risk of missed doses; for example, ensuring stocks are available; setting recurring dose alarms for patients and carers; and adding timings to labels, summary care records/medicines reconciliations and drug charts, depending on area of practice.

Advanced therapies

Advanced therapies are generally non-oral therapy options, which are used when patients are no longer sensitive to oral drug therapy or are experiencing significant fluctuations, such as sudden and unpredictable severe off periods. Deep brain stimulation, apomorphine, levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel, levodopa-carbidopa-entacapone intestinal gel and foslevodopa-foscarbidopa solution for subcutaneous infusion can help symptom management for patients with advanced PD[32].

Management of non-motor symptoms

Perhaps surprisingly, non-motor symptoms are reported to have the biggest impact on quality of life[3]. First-line management may be non-pharmacological and pharmacists can signpost to and work with other health and social care professionals involved in a patient’s care (e.g. speech and language therapists in the management of drooling). Non-motor symptoms are common but underreported, and there is a lack of quality evidence for their management[33]. From the evidence that does exist and experience in clinical practice, some treatment options are established.

Constipation

Autonomic dysfunction is common in PD and often presents as constipation. Muscles in the bowel wall slow down, making it difficult for food to move along the gastro-intestinal tract[34]. It is important this is managed, as constipation can also affect absorption of medication and exacerbate symptoms. Macrogol, an osmotic laxative, is a first-line therapy for treating constipation. Alternative laxatives may be tried if macrogol is not effective. In addition, ensuring a high-fibre diet, exercise (if possible) and adequate fluid intake to prevent constipation should be encouraged[33].

Excessive daytime sleeping

PD medications, particularly dopamine agonists, can cause excessive daytime sleepiness or sudden onset of sleep. People with PD are also more inclined to excessively sleep in the day owing to interrupted sleep at night. NICE guidelines recommend the implementation of good sleep hygiene measures — if these are not successful, medications can be adjusted following advice from a specialist. If adjusting the patient’s medications does not work, modafinil can be considered (this should be reviewed every 12 months after initiation by a specialist)[14]. At the point of diagnosis of PD, patients must inform the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency, as driving and medical assessments may need to be carried out[35]. Patients who experience daytime sleepiness or sudden onset of sleep should not drive and should inform their workplace in case of occupational hazards[23].

Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder

REM sleep behaviour is associated with PD and is a prodromal symptom in many cases[8]. Patients with REM sleep disorder often physically act out vivid dreams during REM sleep, which can affect their quality of life and that of their family and carers. NICE recommends the off-label use of clonazepam or melatonin (pharmacists should ensure off-label use is managed in line with local policy)[14]. Benzodiazepines are cautioned in the elderly population; therefore, this patient cohort must be monitored closely by their care team if started on clonazepam[23].

Nocturnal akinesia

Some people with PD have difficulty moving their body during sleep, which causes them to stay in the same position for prolonged periods. This is known as nocturnal akinesia. It can lead to complications such as pressure sores, breathing disorders and aspiration. It can be helped with slow-release levodopa at night or oral, long-acting dopamine agonists. A rotigotine patch may also be considered; however, there is limited evidence that rotigotine is effective for nocturnal akinesia[7].

Orthostatic hypotension

Also known as postural hypotension, orthostatic hypotension is defined as a fall in blood pressure on standing; it can increase the risk of falls and so requires management. A medication review should be undertaken to address pharmacological causes, such as antihypertensives or anticholinergics. Other factors, such as dehydration, should also be considered. Although evidence in PD is lacking, midodrine can be used to treat orthostatic hypotension[33]. In this case, midodrine will only usually be initiated under the guidance of a PD specialist for orthostatic hypotension if deemed appropriate. If midodrine is contraindicated, fludrocortisone can be used (taking into consideration its safety profile [e.g. cardiac risks])[14,33].

Depression

Approximately 50% of people with PD experience depression[8]. These patients will require specialist review. The NICE guideline on depression in adults with a chronic physical health condition provides further guidance on appropriate antidepressants[36].

Psychotic symptoms

Usually a side effect from dopaminergic medications, psychotic symptoms can cause patients to experience visual hallucinations or delusions[23]. The first option for management is specialist review and consideration of dopaminergic therapy dose reductions, particularly for patients on dopamine agonists. Where medication reduction is not appropriate, does not successfully manage psychosis, or where PD medications are optimised but symptoms continue to be problematic, antipsychotics can be considered.

Typical antipsychotics are best avoided, as they block dopamine D2 receptors. Atypical antipsychotics are preferred; although they block dopamine receptors, they have a lower affinity and occupancy for dopaminergic receptors and a higher degree of occupancy of serotoninergic receptors. Clozapine is recognised as the gold standard; however, clinicians are often deterred from initiating clozapine owing to the monitoring profile of the drug. Therefore, quetiapine is often prescribed for psychotic symptoms in patients with PD[33]. Olanzapine, risperidone and other antipsychotic medications, such as phenothiazines and butyrophenones, should be avoided as they can worsen motor features of PD by blocking dopamine receptors more potently[23,37].

Parkinson’s disease dementia

NICE recommends treating PD dementia with cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g. rivastigmine) or a glutamate receptor antagonist (e.g. memantine). However, there is a risk of cognitive impairment with antimuscarinic medicines (e.g. oxybutynin, amitriptyline or tolterodine) and benzodiazepines. Therefore, treatment of PD dementia should be initiated under guidance from a specialist after careful consideration of comorbidities and risk of adverse effects, and a full medication review[14].

Drooling of saliva

Pharmacological management for drooling of saliva should only be considered if speech and language therapy is not available or has not been effective. Glycopyrronium bromide, hyoscine hydrobromide patch and sublingual atropine can be used to manage hypersalivation. Owing to reduced ability to cross the blood–brain barrier and, therefore, reduced risk of cognitive side effects, glycopyrronium bromide is often preferred in PD. If not successful, referral should be made to a specialist for review and consideration of botulinum toxin type A[7,14,38].

Opportunities for input from pharmacy professionals

As there is no cure for PD, medication management is crucial in managing the disease. Pharmacy professionals can play a significant role in both primary and secondary care. It is important that pharmacy professionals are familiar with PD symptoms and are aware of which referral pathway is most suitable for the patient. Many of the symptoms are straightforward to manage; for example, constipation, and simple interventions (see Table 4) can make a big difference to the patient’s quality of life.

Pharmacy professionals should also be aware of local services that are available to both patients and themselves. The Parkinson’s UK website provides support and resources for healthcare professionals, patients and their family or carers[39].

Conclusion

The management of PD is heavily reliant on medicines. Pharmacy professionals, therefore, have an opportunity to make a real, positive difference to the lives of people with PD. Even simple interventions can significantly improve quality of life, with no special expertise required. As many healthcare professionals are involved in the care of people with PD, it is essential for pharmacy professionals to be knowledgeable about the different referral pathways and interventions available to provide high-quality, individualised, holistic care.

- This article was updated on 29 June 2022 to add additional information

This article has been reviewed and updated by the authors to ensure it remains relevant, following its original publication in June 2022.

- 1Gepshtein S, Li X, Snider J, et al. Dopamine Function and the Efficiency of Human Movement. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2014;26:645–57. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00503

- 2Motor symptoms of Parkinson’s. Parkinson’s UK. 2020.www.parkinsons.org.uk/information-and-support/motor-symptoms-parkinsons (accessed Jun 2022).

- 3Prakash KM, Nadkarni NV, Lye W-K, et al. The impact of non-motor symptoms on the quality of life of Parkinson’s disease patients: a longitudinal study. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:854–60. doi:10.1111/ene.12950

- 4Sonne J, Reddy V, Beato M. Neuroanatomy, Substantia Nigra. National Library of Medicine. 2021.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536995/ (accessed Jun 2022).

- 5Reporting on Parkinson’s: information for journalists. Parkinson’s UK. 2022.www.parkinsons.org.uk/about-us/reporting-parkinsons-information-journalists (accessed Jun 2022).

- 6Parkinson’s disease: How common is it? National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/parkinsons-disease/background-information/prevalence/ (accessed Jun 2022).

- 7Fraint A. Parkinson’s disease. BMJ Best Practice. 2022.https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/147 (accessed Jun 2022).

- 8Chaudhuri K, Fung V. Fast Facts: Parkinson’s Disease. 4th ed. Oxford: : Health Press 2016.

- 9Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P, Brown RG, et al. The metric properties of a novel non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson’s disease: Results from an international pilot study. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1901–11. doi:10.1002/mds.21596

- 10Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. 2008;23:2129–70. doi:10.1002/mds.22340

- 11Hustad E, Aasly JO. Clinical and Imaging Markers of Prodromal Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2020;11. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.00395

- 12Politis M, Niccolini F. Serotonin in Parkinson’s disease. Behavioural Brain Research. 2015;277:136–45. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.037

- 13Bloem BR, Okun MS, Klein C. Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet. 2021;397:2284–303. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00218-x

- 14Parkinson’s disease in adults. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71/chapter/recommendations (accessed Jun 2022).

- 15Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30:1591–601. doi:10.1002/mds.26424

- 16How is Parkinson’s diagnosed? Parkinson’s UK. 2018.www.parkinsons.org.uk/information-and-support/how-parkinsons-diagnosed (accessed Jun 2022).

- 172019 UK Parkinson’s Audit: Summary report. UK Parkinson’s Excellence Network. 2020.https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-07/CS3524%20Parkinson%27s%20UK%20Audit%20-%20Summary%20Report%202019.pdf (accessed Jun 2022).

- 18Diet and nutrition. Parkinson’s Foundation. 2021.https://www.parkinson.org/Living-with-Parkinsons/Managing-Parkinsons/Diet-and-Nutrition (accessed Jun 2022).

- 19Stages of Parkinson’s. Parkinson’s Foundation. 2021.www.parkinson.org/Understanding-Parkinsons/What-is-Parkinsons/Stages-of-Parkinsons (accessed Jun 2022).

- 20Providing better support to people with Parkinson’s in the community and preventing unnecessary hospital admissions . Parkinson’s Excellence Network. 2017.www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2017-12/providing_better_support_to_people_with_parkinsons.pdf (accessed Jun 2022).

- 21PD MED Collaborative Group. Long-term effectiveness of dopamine agonists and monoamine oxidase B inhibitors compared with levodopa as initial treatment for Parkinson’s disease (PD MED): a large, open-label, pragmatic randomised trial. The Lancet. 2014;384:1196–205. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60683-8

- 22Drug treatments for Parkinson’s. Parkinson’s UK. 2019.www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-12/Drug%20treatment%20for%20Parkinson%27s%20booklet%20web.pdf (accessed Jun 2022).

- 23British National Formulary. MedicinesComplete. 2022.https://about.medicinescomplete.com/publication/british-national-formulary/ (accessed Jun 2022).

- 24Stocchi F, Tagliati M, Olanow CW. Treatment of levodopa-induced motor complications. Mov. Disord. 2008;23:S599–612. doi:10.1002/mds.22052

- 25Entacapone Mylan 200 mg film-coated tablets. Electronic medicines compendium. 2017.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8818/smpc#gref (accessed Jun 2022).

- 26Ongentys 50 mg hard capsules. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7386#gref (accessed Jun 2022).

- 27Ergot-derived dopamine agonists: risk of fibrosis. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2008.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/ergot-derived-dopamine-agonists-risk-of-fibrosis (accessed Jun 2022).

- 28Corvol J-C, Artaud F, Cormier-Dequaire F, et al. Longitudinal analysis of impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2018;91:e189–201. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000005816

- 29Parkinson’s disease (QS164). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs164 (accessed Jun 2022).

- 30Eldepryl 5mg Tablets. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2251/pil#gref (accessed Jun 2022).

- 31Get It On Time. Parkinson’s UK. 2022.https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/get-involved/get-it-time (accessed Jun 2022).

- 32Dijk JM, Espay AJ, Katzenschlager R, et al. The Choice Between Advanced Therapies for Parkinson’s Disease Patients: Why, What, and When? JPD. 2020;10:S65–73. doi:10.3233/jpd-202104

- 33Seppi K, Ray Chaudhuri K, Coelho M, et al. Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease—an evidence‐based medicine review. Mov Disord. 2019;34:180–98. doi:10.1002/mds.27602

- 34Bladder and bowel problems. Parkinson’s UK. 2020.https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/information-and-support/bladder-and-bowel-problems (accessed Jun 2022).

- 35Parkinson’s disease and driving. UK Government. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/parkinsons-disease-and-driving (accessed Jun 2022).

- 36Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: recognition and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2009.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg91/chapter/Context (accessed Jun 2022).

- 37Medications To Be Avoided Or Used With Caution in Parkinson’s Disease. American Parkinson’s Disease Association. 2018.https://www.apdaparkinson.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/APDA19360-Medications-to-Avoid-Supplement-D2V1-002.pdf (accessed Jun 2022).

- 38McGeachan AJ, Mcdermott CJ. Management of oral secretions in neurological disease. Pract Neurol. 2017;17:96–103. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2016-001515

- 39Resources for professionals. Parkinson’s UK. 2022.https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/professionals/resources-professionals (accessed Jun 2022).

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Parkinson's disease is a neurodegenerative disorder marked by motor impairments caused by the damage of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and the formation of Lewy bodies. The specific cause of the sickness, however, is unclear. It affects the upper and lower extremities including facial muscles. An increase in the frequency of the disease over the last decade has necessitated greater research to develop advanced diagnostic tests and therapeutic regimens that would provide a lasting cure for Parkinson's disease.