Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Identify the common signs, symptoms and types of miscarriages;

- Identify the risk factors associated with miscarriage and how these can be modified;

- Understand the options for management of miscarriage;

- Understand how pharmacists can help patients and partners who are experiencing, or who have experienced, a miscarriage;

- Signpost patients to further information and support.

Miscarriage is the spontaneous loss of pregnancy during the first 23 weeks of gestation. It is a common experience where the products of conception (embryo or foetus and pregnancy tissue) detach from the uterus and pass through the vagina naturally, or with medical or surgical intervention[1].

In 2020, 716,704 births were registered in the UK; however it is estimated that up to 1 in 4 women will miscarry during their pregnancy[2]. This is likely to be an underestimate as women can miscarry without realising they are pregnant, or they may miscarry without seeking medical attention[3].

This article explores the important role of pharmacists in positively impacting pregnancy, from providing information about suitable medication choices; helping patients to modify and reduce the risk factors associated with miscarriage during preconception and early pregnancy; and signposting to support available in the event of a miscarriage.

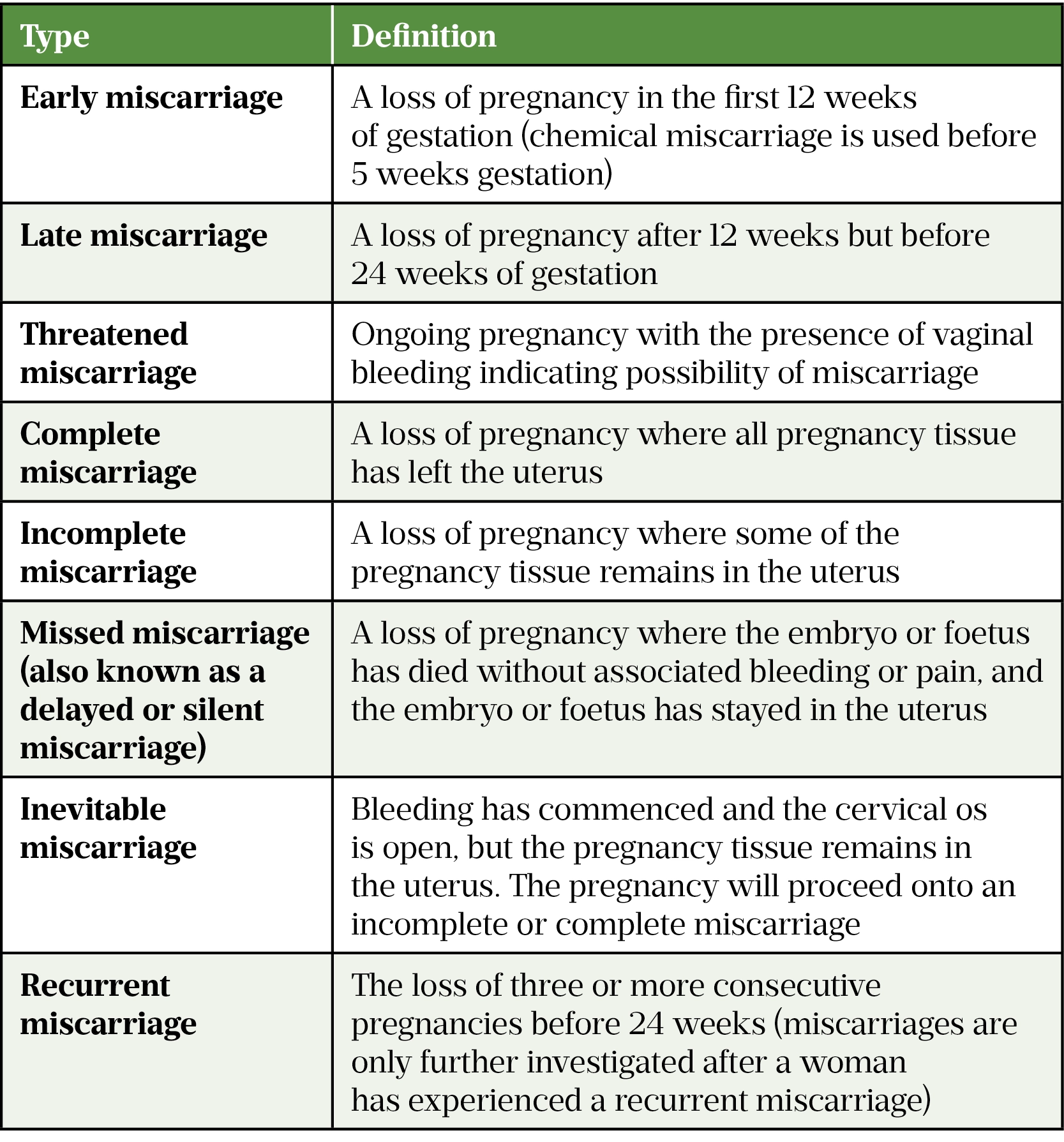

Types of miscarriage

The main types of miscarriage have been defined by the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG); these are summarised in Table 1[4,5].

There are also different types of pregnancies that result in miscarriage. These include:

- An ectopic pregnancy that normally develops in the fallopian tubes instead of the womb, but could also develop in the abdominal cavity;

- A pregnancy of unknown location when the pregnancy test is positive and where the foetus implants itself incorrectly outside of the uterus and is not always possible to determine the location of the pregnancy;

- A molar pregnancy when there is little or no development of the foetus from conception[6].

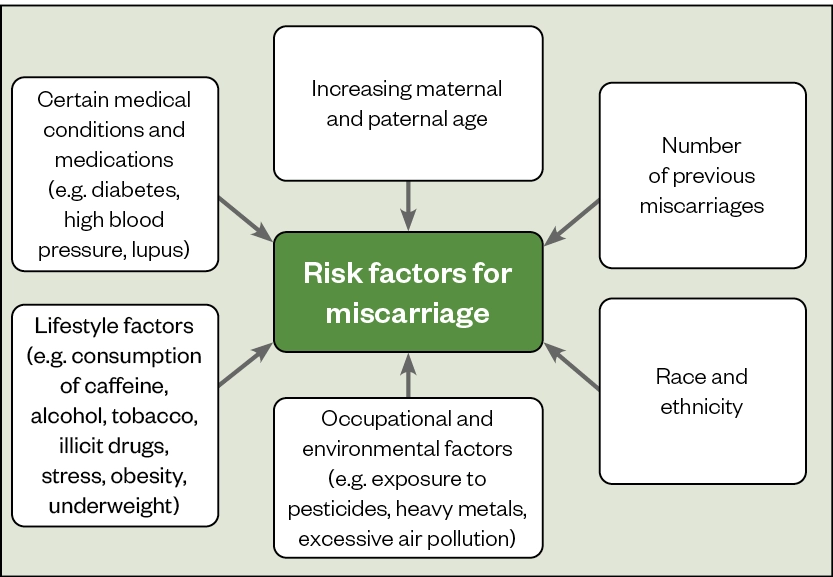

Risk factors and causes

Although most miscarriages happen unexpectedly, the known risk factors are shown in the Figure below[7–10].

Increasing maternal age, in particular in women aged over 35 years, significantly increases the risk of miscarriage owing to a decline in the number and quality of remaining oocytes[11]. Similarly, paternal age can also contribute to an increase in the number of chromosomal abnormalities in sperm.

Race has also been shown to affect the risk of miscarriage — research suggests that black women are 43% more likely to experience a miscarriage compared with white women[12].

The following medicines can cross the placenta and have been shown to potentially increase the chance of miscarriage[13–19]:

- Certain antibiotics (e.g. clarithromycin, azithromycin, metronidazole, sulphonamides, tetracyclines, quinolones);

- Certain antifungals (e.g. oral fluconazole);

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (all except aspirin);

- Methotrexate;

- Retinoids (e.g. oral retinoids);

- Misoprostol.

It is important to note that most research in this area is impacted by confounding factors (e.g. severity of infection), which can also contribute to the increase in risk.

Women are encouraged to continue taking long-term medicines during pregnancy unless otherwise advised by a healthcare professional. Sodium valproate is an exception here and upon pregnancy, patients taking this drug should make an appointment as soon as possible to discuss a suitable alternative[20,21] and should also consult a healthcare professional before attempting to conceive. Prescribing in pregnancy should always opt for the lowest systemic exposure to minimise adverse effects.

It is not always possible to know why a miscarriage has happened and this must be explained to the woman and her partner, if applicable. This can be upsetting and difficult to come to terms with.

Some of the main causes of miscarriage include[22]:

- Genetic factors (e.g. chromosomal abnormalities);

- Hormonal factors;

- Endocrine disorders (e.g. diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome);

- Blood clotting issues (e.g. factor V Leiden);

- Infection (e.g. sexually transmitted diseases, German measles);

- Immune system disorders (e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome);

- Anatomical causes (e.g. shape of the cervix or uterus and fibroids).

Symptoms

The most common symptom of a miscarriage is vaginal bleeding, which varies from light brown spotting to bright red heavy bleeding or passing blood clots. Bleeding may occur continuously or intermittently over several days[23].

Other symptoms of miscarriage may also be present, including[24,25]:

- Pain or cramping in the lower abdomen;

- Discharge of fluid from the vagina (waters may break in a late miscarriage);

- Discharge of tissue from the vagina;

- Loss of pregnancy symptoms (e.g. nausea and breast tenderness), in particular if a woman was experiencing strong pregnancy symptoms that abruptly reduce or stop before 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Experiencing a miscarriage can affect people very differently. Some patients will not notice anything; others will experience some of the symptoms above and then realise they have miscarried when attending an antenatal appointment or ultrasound scan. Pharmacists should advise women experiencing any of the symptoms listed above to consult with a GP or midwife, or attend their local hospital accident and emergency (A&E) department[1].

Healthcare professionals in a primary care setting must act quickly in providing advice and support to a patient they suspect may be experiencing a miscarriage.

Appropriate steps that can be taken during a suspected miscarriage include:

- The use of a clean sanitary towel in the event of bleeding (tampons should be avoided to minimise the risk of infection);

- Paracetamol can be taken safely during pregnancy to manage pain if needed;

- Advise the patient that their individual health and that of the foetus needs to be checked;

- Establish if the patient has registered for antenatal care and, if so, advise them to contact the team or otherwise go to their GP, nearest emergency gynaecology unit or A&E department;

- Advise the patient that it is important to stay calm and encourage them to contact their partner, a family member or friend for support, if appropriate.

Diagnosis

Clinical symptoms and history taking is important in the diagnosis of a miscarriage. A transvaginal ultrasound scan (TVUSS) will confirm viability of the pregnancy and the presence or absence of a fetal heartbeat. A repeat TVUSS may be required after seven days if the first scan was unable to find the location of pregnancy, or the foetus is too small to visualise a heartbeat. Patients sometimes refuse TVUSS, in which case a transabdominal scan can be offered, where the probe is alternatively placed externally on the abdomen[26,27]. However, a transvaginal scan provides greater accuracy.

Biochemical markers of hormones are not routinely part of the diagnosis of a miscarriage as the levels of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) — the hormone produced in pregnancy — can remain raised for several weeks after a miscarriage[28]. Low progesterone levels can indicate a failing pregnancy, although these levels are rarely taken in clinical practice.

Neither a hCG and/or progesterone level should be taken in isolation to diagnose a miscarriage[28].

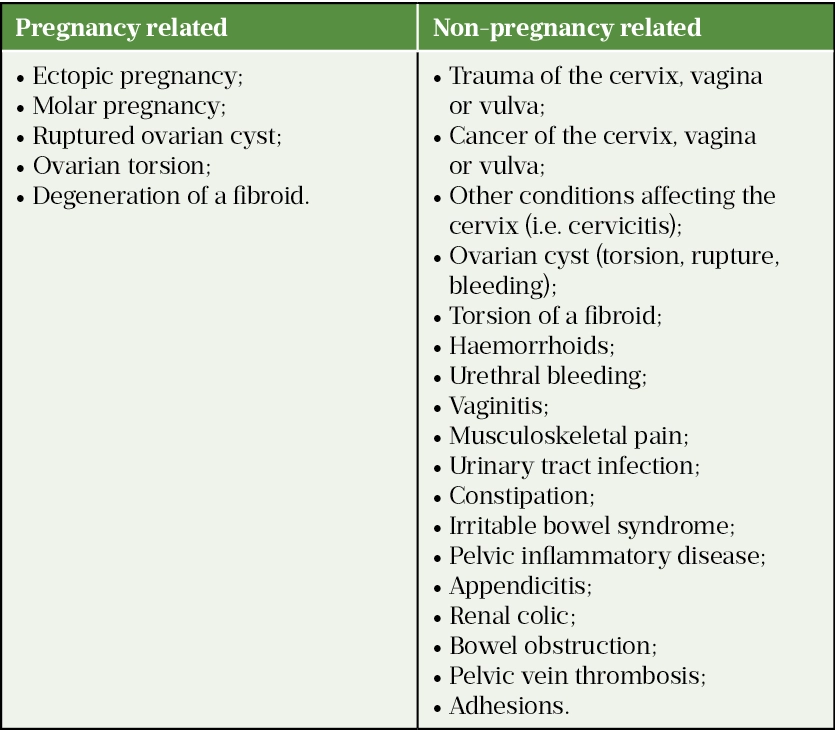

The use of the diagnostic tools above usually allows for the straightforward and accurate diagnosis of a miscarriage. However, vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain can be linked with other pregnancy related or non-pregnancy related causes and differential diagnosis will be required (see Table 2[28]).

Management of miscarriage

The approach to management of miscarriage depends on when it occurred during the pregnancy and how it happened. For instance, in an early miscarriage, if a complete miscarriage has occurred, no pregnancy tissue is left in the uterus and therefore no treatment is required. However, if tissue remains in the uterus (an incomplete miscarriage), management of the miscarriage is required.

In contrast, late miscarriage may need to be managed differently to an early miscarriage. During a late miscarriage, passing the foetus naturally will likely resemble the process of labour and the woman giving birth.

Healthcare professionals should communicate with patients about diagnosis and provide advice on the best options for treatment to help them make an informed decision. Verbal and written information should be provided.

There are three treatment options for miscarriage: expectant management, medical management and surgical management. Medical or surgical management may be explored if the woman is at increased risk of haemorrhage, has had a previous adverse and/or traumatic experience associated with pregnancy or has an infection[1].

Expectant management

The first line management for women diagnosed with a miscarriage is expectant management, also known as ‘watchful waiting’, where the patient waits for the miscarriage to occur naturally at home, without the need for medical or surgical intervention. This type of management is expected to be successful in 50% of women[29].

Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) says that expectant management should be followed for 7–14 days, although uncertainty exists around the optimal duration and an individualised approach to expectant management should be taken[30].

Medical management

Pharmacological treatment for miscarriage is used to help stimulate uterine expulsion of the foetus and pregnancy tissues. Medical management is successful in 85% of women and some local hospitals will allow women to go home while the miscarriage completes[29]. As with expectant management, medical management avoids the risks associated with surgery (see below). The primary medicines used when managing a miscarriage are mifepristone, misoprostol and anti-D immunoglobulin.

Mifepristone

The anti-progesterone mifepristone sensitises the myometrium to prostaglandin induced contractions[31,32]. Results from the MifeMiso trial have shown pre-treatment with mifepristone followed by misoprostol (see below) results in a higher rate of resolution of missed miscarriage by seven days, compared with misoprostol alone, and therefore the recommendation would be for combination treatment with misoprostol taken 24–48 hours after mifepristone[31,33].

Mifepristone can cause abdominal cramps and vaginal bleeding that can be severe. Other common side effects include nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. Uncommon adverse effects include hypotension, skin reactions and, rarely, headache, chills, angioedema and single cases of urticaria, erythema nodosum, toxic epidermal necrolysis and uterine rupture[32].

Misoprostol

The prostaglandin analogue misoprostol acts by binding to myometrial cells inducing contractions[31,34]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance currently recommends vaginal administration of misoprostol, inserted high into the vagina[29]. Alternatively, misoprostol can be given orally. Misoprostol causes stimulation of the uterus to expel the pregnancy and, as a result, the woman may experience uterine and abdominal cramping and bleeding.

Misoprostol is commonly available as 200 microgram tablets. Dosage varies depending on the type of miscarriage: for a missed miscarriage, a single dose of 800 micrograms of misoprostol is to be given; for incomplete miscarriages, a single dose of 600 micrograms of misoprostol is to be given. However, 800 micrograms can also be used as an alternative to allow alignment of treatment protocols for both missed and incomplete miscarriage[29].

Misoprostol can cause other common side effects, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, headache, dizziness, fever and chills. Side effects with misoprostol occur more commonly when it is administered orally compared to vaginal administration, and are primarily gastrointestinal effects[34].

Anti-D immunoglobulin

Rhesus disease can occur during pregnancy and results from an incompatibility between the woman’s and foetus’ blood[35]. The mother’s immune system can generate antibodies against the foetus’ RhD positive antigens — a process known as sensitisation — affecting the foetus and typically causing two main problems: haemolytic anaemia and jaundice[35]. Anti-D immunoglobulin neutralises any RhD positive antigens that have entered the woman’s blood, thereby preventing rhesus disease[35].

In a miscarriage at 12 or more weeks gestation, an intramuscular injection of anti-D immunoglobulin is offered to all rhesus-negative women who have had a surgical procedure to manage the miscarriage[36]. This is to stop the mother forming antibodies that will reside in the bloodstream and could have the potential to cause rhesus disease in future pregnancies.

Surgical management

If the products of conception are retained despite medical management, or if the patient is haemodynamically compromised owing to excessive bleeding or infection, surgical management is indicated. It is successful in 95% of women[30].

Women are offered a choice of[30]:

- Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA), which uses a suction device to remove the pregnancy (under local anaesthetic). This can be carried out in an outpatient or clinic setting;

- Surgery procedure in theatre (under general anaesthetic).

In more recent years, MVA has become increasingly common practice[37].

Complications of surgical management are uncommon, they include:

- Heavy bleeding;

- Infection;

- Potential for the operation to be repeated if not all pregnancy tissue is removed;

- Perforation of the womb;

- Adhesions or scar tissue in the womb[38].

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Results from the ‘Antibiotics in Miscarriage Surgery’ (AIMS) trial showed that antibiotic prophylaxis before miscarriage surgery did not result in a significantly lower risk of pelvic infection than placebo[39]. However, when viewed holistically, the wider benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis make it more effective and less expensive overall compared with no antibiotic prophylaxis, and low-income countries may take this approach depending on access to safe and effective surgical care in the area[40].

Complications

The main complications of miscarriage are infection, bleeding, clots and depression. Table 3 summarises signs and symptoms for each of these complications[41].

Prevention

Although the cause of a miscarriage is often unknown, many of the risk factors described previously can be modified and reduced. Eating a healthy, balanced diet, limiting caffeine intake, losing weight before pregnancy if overweight or obese, staying active and abstaining from drinking alcohol, smoking or using illegal drugs can all reduce the risk of miscarriage.

Other pre-conception planning and support can be provided including[42]:

- Avoiding over-the-counter medicines, such as ibuprofen for pain relief or fluconazole for thrush, without discussing with a healthcare professional first;

- Managing any existing medical conditions, such as diabetes or high blood pressure;

- Being up to date with vaccinations, particularly against rubella because contracting this virus increases the risk of miscarriage and birth defects;

- Registering for antenatal care as soon as possible after conceiving and attending all antenatal appointments and scans from the start of pregnancy;

- Avoiding certain foods, such as raw or undercooked meat (which can cause toxoplasmosis), liver and other food products containing vitamin A; meat and vegetarian/vegan patés (which can cause listeriosis); and unpasteurised milk or dairy products (which can cause food poisoning from toxoplasmosis, listeriosis and campylobacter);

- Treating and managing any identified causes of miscarriage, such as antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), to prevent further miscarriages.

Treatment with progesterone for vaginal bleeding

NICE currently recommends the use of vaginal micronised progesterone 400mg twice daily to women with an intrauterine pregnancy if they have vaginal bleeding and have previously experienced a miscarriage. If a foetal heartbeat is confirmed, progesterone can be continued until 16 weeks gestation[30]. This is an off-label use of progesterone, and this treatment offers an increased chance of a successful birth for this patient group. This treatment option is not recommended for patients with no history of a previous miscarriage.

Aspirin and heparin

For patients with APS and recurrent miscarriage, treatment with aspirin and heparin can also improve pregnancy outcomes and reduce the risk of miscarriage.

Counselling, recovery and future pregnancy

There are various steps that can be taken to help the physical and mental health recovery of both the patient and partner following miscarriage and when considering future pregnancy:

Emotional wellbeing

- Acknowledge that the cause of the miscarriage is likely to be unknown and it is highly unlikely to have been the result of anything that the woman/partner did or didn’t do;

- Encourage them to draw on their support network as much as possible (e.g. partner, family, friends, organisations such as the Miscarriage Association);

- Emphasise the importance of allowing time to process emotions, including grief, guilt and shame;

- Explain how they can access counselling services for further support.

Going back to usual activities/work

- Depending on individual circumstances, time may be needed to allow for both physical and emotional recovery before resuming usual activities.

Pregnancy after a miscarriage

- It is possible to try to conceive again after a miscarriage if a couple would like to;

- If awaiting investigations following a recurrent miscarriage, it may be worth waiting for these results first;

- Women can be fertile in the month after a miscarriage, so be cautious/use contraception if another pregnancy is not wanted so soon after a miscarriage;

- Highlight the risk factors and potential modifying steps that can be taken to reduce risk of future miscarriage.

- 1Miscarriage. NHS. 2022.https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/miscarriage/ (accessed May 2022).

- 2Baby loss statistics. Tommy’s. https://www.tommys.org/baby-loss-support/pregnancy-loss-statistics (accessed May 2022).

- 3Miscarriage . Miscarriage Association . https://www.miscarriageassociation.org.uk/media-queries/background-information (accessed May 2022).

- 4Types of miscarriage. Tommy’s. : https://www.tommys.org/baby-loss-support/miscarriage-information-and-support/types-of-miscarriage (accessed May 2022).

- 5Miscarriage: What is it? National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/miscarriage/background-information/definition/ (accessed May 2022).

- 6About molar pregnancy. Cancer Research UK. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/gestational-trophoblastic-disease-gtd/molar-pregnancy/about (accessed May 2022).

- 7Tahseen S, James C. Spotlight: management of recurrent miscarriages. British Journal of Family Medicine. 2017.https://www.bjfm.co.uk/practical-guidance-to-management-of-miscarriages (accessed May 2022).

- 8Prager S, Micks E, Dalton V. Pregnancy loss (miscarriage): Terminology, risk factors, and etiology. UpToDate. 2021.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pregnancy-loss-miscarriage-terminology-risk-factors-and-etiology (accessed May 2022).

- 9Miscarriage: What are the causes and risk factors? National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/miscarriage/background-information/causes-risk-factors/ (accessed May 2022).

- 10UK National Guideline for the management of Bacterial Vaginosis 2012. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH). 2012.https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1041/bv-2012.pdf (accessed May 2022).

- 11The Investigation and Treatment of Couples with Recurrent Miscarriage (Green-top Guideline No. 17). Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. 2011.https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/browse-all-guidance/green-top-guidelines/the-investigation-and-treatment-of-couples-with-recurrent-miscarriage-green-top-guideline-no-17/ (accessed May 2022).

- 12RCOG calls for urgent research into miscarriage rates. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. 2022.https://www.rcog.org.uk/news/rcog-calls-for-urgent-research-into-miscarriage-rates/ (accessed May 2022).

- 13Muanda FT, Sheehy O, Bérard A. Use of antibiotics during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion. CMAJ. 2017;189:E625–33. doi:10.1503/cmaj.161020

- 14Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association Between Use of Oral Fluconazole During Pregnancy and Risk of Spontaneous Abortion and Stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.17844

- 15Nakhai-Pour HR, Broy P, Sheehy O, et al. Use of nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during pregnancy and the risk of spontaneous abortion. CMAJ. 2011;183:1713–20. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110454

- 16Li D-K, Ferber JR, Odouli R, et al. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs during pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018;219:275.e1-275.e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.06.002

- 17Weber-Schoendorfer C, Chambers C, Wacker E, et al. Pregnancy Outcome After Methotrexate Treatment for Rheumatic Disease Prior to or During Early Pregnancy: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2014;66:1101–10. doi:10.1002/art.38368

- 18Oral retinoids and pregnancy prevention – what you need to know. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2019.https://www.rpharms.com/about-us/news/details/Oral-retinoids-and-pregnancy-prevention—what-you-need-to-know (accessed May 2022).

- 19Andersen JT, Mastrogiannis D, Andersen NL, et al. Diclofenac/misoprostol during early pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;294:245–50. doi:10.1007/s00404-015-3966-9

- 20Mahase E. Sodium valproate continues to be prescribed in hundreds of pregnancies, data show. BMJ. 2022;:o1013. doi:10.1136/bmj.o1013

- 21Guidance Valproate use by women and girls. MHRA. 2018.https://www.gov.uk/guidance/valproate-use-by-women-and-girls#:~:text=Valproate%20must%20no%20longer%20be,need%20to%20avoid%20becoming%20pregnant (accessed May 2022).

- 22What causes a miscarriage? Tommy’s. https://www.tommys.org/baby-loss-support/miscarriage-information-and-support/causes-miscarriage (accessed May 2022).

- 23Miscarriage: When should I suspect a miscarriage? National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/miscarriage/diagnosis/when-to-suspect-miscarriage/ (accessed May 2022).

- 24Miscarriage: signs and symptoms. Tommy’s. https://www.tommys.org/baby-loss-support/miscarriage-information-and-support/miscarriage-symptoms (accessed May 2022).

- 25Sapra KJ, Joseph KS, Galea S, et al. Signs and Symptoms of Early Pregnancy Loss. Reprod Sci. 2016;24:502–13. doi:10.1177/1933719116654994

- 26Jurkovic D, Overton C, Bender-Atik R. Diagnosis and management of first trimester miscarriage. BMJ. 2013;346:f3676–f3676. doi:10.1136/bmj.f3676

- 27Information for you – Early miscarriage. Early Miscarriage Leaflet. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. 2016.https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/patients/patient-information-leaflets/pregnancy/pi-early-miscarriage.pdf (accessed May 2022).

- 28Prager S, Micks E, Dalton V. Pregnancy loss (miscarriage): Clinical presentations, diagnosis, and initial, evaluation. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pregnancy-loss-miscarriage-clinical-presentations-diagnosis-and-initial-evaluation/print (accessed May 2022).

- 29Miscarriage management. Tommy’s. https://www.tommys.org/baby-loss-support/miscarriage-information-and-support/miscarriage-management (accessed May 2022).

- 30Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management. NICE guideline [NG126]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng126 (accessed May 2022).

- 31Chu JJ, Devall AJ, Beeson LE, et al. Mifepristone and misoprostol versus misoprostol alone for the management of missed miscarriage (MifeMiso): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2020;396:770–8. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31788-8

- 32MIFEPRISTONE. British National Formulary . https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/mifepristone.html (accessed May 2022).

- 33Hamel C, Coppus S, van den Berg J, et al. Mifepristone followed by misoprostol compared with placebo followed by misoprostol as medical treatment for early pregnancy loss (the Triple M trial): A double-blind placebo-controlled randomised trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;32:100716. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100716

- 34MISOPROSTOL SIDE EFFECTS. British National Formulary . https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/misoprostol.html#sideEffects (accessed May 2022).

- 35Routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis for women who are rhesus D negative. Technology appraisal guidance [TA156]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2008.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta156 (accessed May 2022).

- 36Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfusion Med. 2014;24:8–20. doi:10.1111/tme.12091

- 37Kakinuma T, Kakinuma K, Sakamoto Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of manual vacuum suction compared with conventional dilatation and sharp curettage and electric vacuum aspiration in surgical treatment of miscarriage: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-03362-4

- 38Nanda K, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Expectant care versus surgical treatment for miscarriage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003518.pub3

- 39Lissauer D, Wilson A, Daniels J, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics to reduce pelvic infection in women having miscarriage surgery – The AIMS (Antibiotics in Miscarriage Surgery) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19. doi:10.1186/s13063-018-2598-3

- 40Goranitis I, Lissauer DM, Coomarasamy A, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in the surgical management of miscarriage in low-income countries: a cost-effectiveness analysis of the AIMS trial. The Lancet Global Health. 2019;7:e1280–6. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(19)30336-5

- 41Why we need to talk about losing a baby. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/why-we-need-to-talk-about-losing-a-baby (accessed May 2022).

- 42Pre-conception – advice and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/pre-conception-advice-management/ (accessed May 2022).