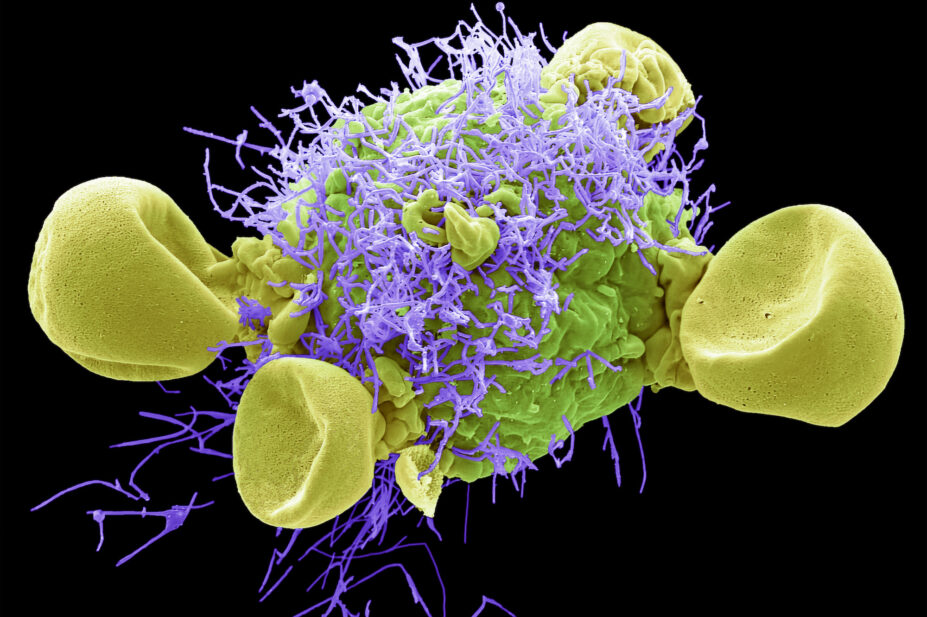

STEVE GSCHMEISSNER/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the pathophysiology and diagnosis of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in children;

- Recognise the potential signs and symptoms of RSV;

- Provide advice on management and prevention of RSV.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is one of the most common causes of lower respiratory tract infection in children and an important contributory factor in adults with lower respiratory tract infections[1,2].

RSV is a highly communicable disease that demonstrates predictable seasonality. Typical activity patterns within the UK emerge in the autumn, peak in the winter and continue into early spring, with most infections presenting over a mid-winter peak period of six weeks and exhibiting varying annual infection rates[3].

In infants and young children, it is the most common cause of hospital admissions for bronchiolitis (an inflammation of the small airway passages entering the lungs), with 2–6% of patients requiring management in a paediatric intensive care unit[4]. More than 60% of children are infected by their first birthday, and more than 80% of children by 2 years of age. The antibodies that develop following early childhood infection do not prevent further RSV infections throughout life[5]. Children who have had RSV bronchiolitis in early life may be at increased risk of developing asthma and wheeze later in childhood[2,3].

In England, approximately 20,000 hospital admissions are recorded annually relating to RSV infections in children aged under 1 year[6]. The burden of RSV in children extends beyond hospital settings, with an estimated 450,000 GP attendances for children and adolescents annually, and an estimated annual cost of around £16–19m in GP consultations for children alone[4].

RSV usually causes a mild self-limiting respiratory infection in adults and children, but it can be severe in infants and adults who are at increased risk of acute lower respiratory tract infection[3]. In older adults, and those with chronic heart and lung disease (e.g COPD, asthma), those who are immunocompromised and those living in nursing homes or long-term facilities, RSV increases the risk of respiratory tract disease, the need for hospitalisations and, subsequently, death[1,2,7]. A RSV vaccine is now licensed for active immunisation for the prevention of lower respiratory tract disease caused by RSV in adults older than 60 years[8,9].

Environmental factors, such as passive smoking in the home, crowded living conditions, air pollution, malnutrition and vitamin D deficiency, can increase RSV susceptibility[2].

Pharmacists may by consulted for advice on treatment strategies for respiratory infections and should be alert to the risks of RSV and potential preventative measures. This article will focus on the management of RSV in neonates and children. For information on RSV in adults please consult: ‘Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunisation programme for infants and older adults: JCVI full statement, 11 September 2023’.

Pathophysiology and transmission

RSV is an enveloped, negative-strand RNA virus of the Paramyxoviridae family within the Pneumovirus genus[3]. The incubation period of RSV varies from two to eight days, with primary infection occurring in respiratory epithelial cells that line nasal passages and the upper respiratory tract[3,10]. An RSV infection evokes an immune response in the host, leading to inflammation and increased mucous production, which in turn progresses to a narrowing of the airway and increased airway resistance[11]. Children are more prone to obstruction and increased airway resistance owing to the high surface area-to-volume ratio of their airways[12].

The virus can be transmitted to other individuals even before presentation of signs and symptoms of RSV infection. Individuals are considered infectious once the virus has replicated and will remain contagious for as long as viral shedding takes place. The period of viral shedding can vary, but typically ranges from 14 days in infants with mild infections, to 3 weeks in infants with severe infections. This period can increase to several months for immunocompromised individuals[2].

RSV is primarily transmitted from respiratory droplets, through direct contact with an infected individual or via indirect contact through contaminated objects or surfaces[6]. Transmission of large respiratory droplets can spread from the nose and mouth of an individual infected with RSV when they cough or sneeze directly to the eyes, nose or mouth of another individual. Fine respiratory droplets that remain airborne may increase an individual’s risk of inhaling the virus, leading to infection within the lower respiratory tract. Droplets containing the virus that land on surfaces can remain infectious for varying lengths of time, depending on the surface type[2]. The virus survives the longest on non-porous surfaces, which can be up to six hours. RSV can therefore also be transmitted easily throughout healthcare settings and among children in close-contact settings[2].

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of RSV infection usually appear three to five days after exposure to the virus[13,14]. The infection usually causes mild cold-like signs and symptoms, which can be managed at home with over-the-counter medications. These symptoms may include:

- Congested or runny nose;

- Dry cough;

- Low-grade fever;

- Sore throat;

- Sneezing;

- Headache[15].

Most children recover in one to two weeks, although a cough can persist for around three weeks[16].

Symptoms can become more severe if RSV infection spreads to the lower respiratory tract, causing pneumonia or bronchiolitis, and patients may present in secondary care with worsening symptoms. Signs and symptoms of bronchiolitis may include:

- Fever;

- Severe cough;

- Noisy breathing (wheezing);

- Rapid breathing or difficulty breathing;

- Bluish colour of the skin, tongue or lips, owing to lack of oxygen (cyanosis)[14,17].

Box 1: Red flag symptoms for RSV

Parents and carers should be advised to call 999 or take the child to A&E if:

- The child has difficulty breathing (grunting noises or tummy sucking under their ribs);

- There are pauses when the child breathes (apnoeas);

- Their skin, tongue or lips are blue;

- The child is floppy and will not wake up or stay awake.

A GP referral may be recommended if:

- Cold-like symptoms are not improving;

- The child is feeding/eating less than normal;

- The child has a dry nappy for 12 hours or more, or is showing any other signs of dehydration;

- A baby aged under 3 months has a temperature of 38⁰C or more, or a baby aged over 3 months has a temperature of 39⁰C or higher;

- A baby feels hot to touch (back/chest) or feels sweaty;

- The child is very tired or irritable[14,17].

Risk factors

Babies and children aged under two years are usually most severely affected by RSV[18]. Risk factors for RSV infection include prematurity; cardiopulmonary disease, such as chronic lung disease or congenital heart disease; immunodeficiency; and may also include other factors, such as tobacco exposure, childcare attendance, overcrowding, lack of breastfeeding, and admission to hospital during the RSV season[3].

Diagnosis

RSV diagnosis is performed using a mixture of history taking, clinical examination and further investigations as needed. RSV has similar features to other viral illnesses, such as influenza, parainfluenza and the common cold; it is therefore important to rule out other differential diagnoses[19]. For more information on how to differentiate between coughs and sore throat symptoms, see the following articles from The Pharmaceutical Journal:

History taking

In younger children and infants, the following symptoms can be indicative of RSV bronchiolitis:

- Poor feeding, apnea, irritability or lethargy;

- Rhinorrhea, cough, sneezing, fever, shortness of breath, wheezing, pharyngitis or respiratory distress;

- Dehydration and reduced urine output, or fewer wet nappies[4].

In older children, RSV can present as an upper respiratory tract infection, viral pneumonia, episodic viral-induced wheeze or an acute exacerbation of asthma, and therefore needs further investigations to rule out other differential diagnoses[4]. This is particularly common in preschool children. Symptom onset and progression can help identify any differences between RSV and other differential diagnoses, including atopic asthma and croup[4].

History taking should include birth history, which may help identify any risk factors, and medications/allergies history to rule out other differentials diagnoses; for example, asthma or allergic rhinitis[4]. It is also important to ask if other family members are unwell, which helps rule out other viral infections.[4].

Social history should also be considered, including the smoking status of parents and household members, as this may exacerbate any symptoms[4].

Clinical examination

A clinical examination should look for the following signs and symptoms:

- Increased respiratory rate;

- Wheeze and crackles on auscultation;

- Respiratory distress, including grunting, nasal flaring, indrawing, intercostal and/or subcostal retractions, colour change/apnoea or abdominal breathing;

- Signs of dehydration[20].

Other investigations

Respiratory viral testing may increase the clinician’s confidence of a viral diagnosis, rather than a bacterial cause, which is a differential diagnosis. Testing is unlikely to have an impact on clinical decision making owing to the short duration of illness, but has numerous benefits, including reducing antibiotic duration and usage as well as reduction of other investigations, such as chest X-rays, blood tests and urinalysis[4]. Testing can also help rule out other viral causes, including SARS-COV pneumonitis[4].

Nasopharyngeal and tracheal testing are more specific; however, for practical purposes, nasal swabs are taken wherever appropriate[21]. Enzyme immunoassay is the most rapid form of testing and is therefore used more frequently; however, it has low sensitivity of between 50–90%, so if symptomatic patients have a negative sample, the diagnosis cannot be ruled out and should be treated as required. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) does not recommend respiratory viral testing if bronchiolitis is suspected[4,14].

Blood tests may be taken to rule out other differential diagnoses; for example, atopic conditions, including asthma[4]. Pulse oximetry would be considered to confirm hypoxia[18]. Chest X-rays may be necessary in children with worsening respiratory distress, as it may show hyperinflation and patchy atelectasis (collapse of the whole lung or an area of the lung), and will rule out other differential diagnoses, such as pneumonitis[18].

Management

Managing RSV requires a multifaceted approach, involving preventive measures, supportive care and, in severe cases, specific antiviral therapies[4].

Infants and immunocompromised patients may require hospitalisation for the following criteria:

- To help maintain adequate hydration, where usual intake volume has reduced by 50–75% or there has been no wet nappy for 12 hours;

- Oxygen therapy for those with persistent saturations in room air of less than 90% in infants aged over 6 weeks and less than 92% in babies aged under 6 weeks, or those of any age with underlying health conditions, apnoea or respiratory distress[14,18].

There is no evidence of benefit from antibiotics unless concurrent bacterial infection has been confirmed. Inhaled or nebulised bronchodilators, nebulised adrenaline, nebulised hypertonic saline, corticosteroids and leukotriene inhibitors have also been found to have no benefit on improving oxygen saturation or reducing hospital admission duration[4,22]. Routine use of these agents is not recommended; however, where there is a family history of asthma, atopy or allergy, a single trial of inhaled bronchodilator therapy may be considered and should be discontinued when there is no clinical improvement following administration[14,23].

Patients with severe infection with worsening respiratory failure may require continuous positive airway pressure or mechanical ventilation with upper airway suctioning[2,14].

Supportive care

For less severe infections, parental advice for care at home involves encouraging fluid intake, treating fever and discomfort with over-the-counter analgesia (paracetamol/ibuprofen as per licence), avoiding exposure to smoking and using bulb suctioning or saline nasal drops to aid nasal congestion relief. Use of saline drops and suctioning should be done before feeds to prevent vomiting, following manufacturer’s instructions[23].

Antiviral therapies

While current interventions focus on symptomatic relief and reducing the severity of the disease, there is ongoing research into novel antiviral agents for more targeted and effective treatments[24].

Ribavirin, a synthetic nucleoside with antiviral activity, has been used in the past for severe RSV cases; however, its clinical efficacy remains unclear[4]. Nebulised ribavirin (6g over 12–18 hours per day, for at least 3 days and a maximum of 7 days) is given via a small particle aerosol generator and usually restricted to immunocompromised, post bone marrow transplant or cardiac compromised patients with severe infection[25]. Unlicensed intravenous ribavirin may be considered for severe, life-threatening RSV; however, both formulations are currently unavailable in the UK, following long-term manufacturing shortages with no expected resolution date[26,27].

Intravenous immunoglobulin has been considered for treating RSV; however evidence of efficacy is limited where, despite a reduction in viral titres, this has not been shown to be of benefit in clinical outcomes[4]. Palivizumab, licensed for prevention of respiratory tract infections caused by RSV, has been trialled as a treatment agent in immunocompromised patients, but has not shown an improvement in mortality, despite reduction in viral load, and requires further research[28,29].

Prevention

Pharmacists can advise on preventive measures in children[2]. The preventive advice provided in Box 2 also applies to other viral illnesses.

Box 2: Preventive measures to prevent RSV in children

- Hand washing: wash hands in soap and water for at least 20 seconds or use a hand sanitiser before touching a baby and remind others to do the same;

- Avoid close contact with infected individuals;

- Clean contaminated surfaces: RSV can live up to six hours on doorknobs, toys or countertops;

- Cover the mouth when sneezing and coughing as the virus is airborne and spread through droplets;

- Cessation of smoking or vaping;

- Open windows to allow air ventilation to prevent indoor air pollution;

- Supplement Vitamin D where malnutrition may be a factor[2].

Passive immunisation is defined as the administration of antibodies to an unimmunised person from an immune subject to gain temporary protection against a specific agent[30]. Programmes providing targeted protection in vulnerable patients at risk of RSV during the first six months of life substantially reduce disease burden and hospital-associated costs[4,31]. Criteria for patients that may benefit from passive immunisation can be seen in Box 3.

Passive immunisation with monoclonal antibodies, such as palivizumab or nirsevimab, has been shown to be safe and effective in high-risk infants[31].

Palivizumab has a half-life of 18–21 days and is currently the most used agent, given via intramuscular injection at a dose of 15mg/kg once per month from the start of RSV season, up to a maximum of 5 doses[3,32].

Nirsevimab, indicated for the prevention of RSV lower respiratory tract disease in neonates and infants during their first RSV season, has a longer half-life of 69 days. The recommended dose is a single dose of 50mg adminstered intramuscularly for children below 5kg in weight and a single dose of 100mg for children who weigh 5kg or above[33].

The JCVI has stated there is no preference between the two monoclonal antibodies, but notes there is expected to be better uptake with nirsevimab owing to its administration as a single dose[34]. In the UK, palivizumab is currently the only commissioned prophylactic agent, with nirsevimab expected to be available for the 2024/2025 RSV season, pending specialised commissioning review[34].

Box 3: Recommended patient criteria for starting passive immunisation

- Pre-term infants with compatible X-ray changes, who continue to receive supplemental oxygen or respiratory support at 36 weeks postmenstrual age;

- Preterm infants with haemodynamically significant, acyanotic congenital heart disease born under 32 weeks postmenstrual age at the start of RSV season;

- Infants with respiratory diseases, who are not necessarily pre-term but remain on oxygen at the start of the RSV season;

- Children aged under 24 months with severe, combined immunodeficiency[3].

There is no paediatric vaccine for RSV; however, there is ongoing research into the development of an effective, tolerated vaccine for multiple target populations[4,34]. A maternal RSV vaccine, developed by Pfizer, has recently been granted a UK licence, following approval from the European Medicines Agency and US Food and Drug Administration[35]. Abrysvo, administered via intramuscular injection, to individuals during weeks 28–36 of their pregnancy has been shown to provide protection against RSV to infants from birth through to 6 months of age.

It is important to note, based on experience with other maternal vaccines (e.g. pertussis), that a maternal vaccine would need to be administered at least two weeks prior to birth to achieve adequate antibody levels in infants, and that premature birth may compromise the amount of maternal antibody available, hence supplemental monoclonal antibodies is likely be required for the majority of premature infants[36].

Best practice

- RSV presents in a similar pattern to other viral illnesses and it is important that a differential diagnosis is made in children at risk of severe complications, such as bronchiolitis;

- Red-flag symptoms should alert pharmacists to the severity of the infection and the need for referral or hospitalisation;

- Pharmacists can advise on preventive and supportive measures in children;

- Hospital pharmacists can ensure that eligible children receive passive RSV immunisation[14,19].

- 1Papi A, Ison MG, Langley JM, et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusion F Protein Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:595–608. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2209604

- 2Kaler J, Hussain A, Patel K, et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus: A Comprehensive Review of Transmission, Pathophysiology, and Manifestation. Cureus. 2023. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.36342

- 3Respiratory syncytial virus: the green book, chapter 27a. UK Health Security Agency. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/respiratory-syncytial-virus-the-green-book-chapter-27a (accessed March 2024)

- 4Barr R, Green CA, Sande CJ, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus: diagnosis, prevention and management. Therapeutic Advances in Infection. 2019;6:204993611986579. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049936119865798

- 5Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV): symptoms, transmission, prevention, treatment. UK Health Security Agency. 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-symptoms-transmission-prevention-treatment/respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-symptoms-transmission-prevention-treatment#uk-health-security-agency-ukhsa-activity (accessed March 2024)

- 6Bardsley M, Morbey RA, Hughes HE, et al. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in England during the COVID-19 pandemic, measured by laboratory, clinical, and syndromic surveillance: a retrospective observational study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2023;23:56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(22)00525-4

- 72024 Gold Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/ (accessed March 2024)

- 8Arexvy powder and suspension for suspension for injection {equilateral_black_triangle}. Electronic medicines compendium. 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/14951 (accessed March 2024)

- 9Baraldi E, Checcucci Lisi G, Costantino C, et al. RSV disease in infants and young children: Can we see a brighter future? Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2022;18. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2079322

- 10Oshansky CM, Zhang W, Moore E, et al. The host response and molecular pathogenesis associated with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Future Microbiology. 2009;4:279–97. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb.09.1

- 11Battles MB, McLellan JS. Respiratory syncytial virus entry and how to block it. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:233–45. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-019-0149-x

- 12Griffiths C, Drews SJ, Marchant DJ. Respiratory Syncytial Virus: Infection, Detection, and New Options for Prevention and Treatment. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:277–319. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00010-16

- 13Polak MJ. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV): overview, treatment, and prevention strategies. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews. 2004;4:15–23. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.nainr.2003.12.007

- 14Bronchiolitis in children: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng9 (accessed March 2024)

- 15Cooper A, Banasiak N, Allen P. Management and prevention strategies for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis in infants and young children: a review of evidence-based practice interventions. Pediatr Nurs. 2003;29:452–6.

- 16Cunningham S. Bronchiolitis. In: Wilmot R, al. et, eds. Kendig’s Disorders of the Respiratory Tract in Children. Elsevier 2019:420–6.

- 17Bronchiolitis. NHS. 2022. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/bronchiolitis/ (accessed March 2025)

- 18Borchers AT, Chang C, Gershwin ME, et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus—A Comprehensive Review. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2013;45:331–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-013-8368-9

- 19What else might cause symptoms of influenza-like illness? National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/influenza-seasonal/diagnosis/differential-diagnosis/ (accessed March 2024)

- 20Friedman JN, Rieder MJ, Walton JM, et al. Bronchiolitis: Recommendations for diagnosis, monitoring and management of children one to 24 months of age. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2014;19:485–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/19.9.485

- 21Eiland LS. Respiratory Syncytial Virus: Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention. The Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2009;14:75–85. https://doi.org/10.5863/1551-6776-14.2.75

- 22Gadomski AM, Scribani MB. Bronchodilators for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd001266.pub4

- 23Evidence-Based Care Recommendations. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. 2024. www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/j/anderson-center/evidence-based-care/recommendations/topic/ (accessed March 2024)

- 24Mejias A, Ramilo O. New options in the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus disease. Journal of Infection. 2015;71:S80–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2015.04.025

- 25Virazole (Ribavirin for Inhaled Solution, USP). Bausch Health. 2019. https://pi.bauschhealth.com/globalassets/BHC/PI/Virazole-PI.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 26Ribavirin. BNF for Children. 2024. https://bnfc.nice.org.uk/drugs/ribavirin/ (accessed March 2024)

- 27Ribavirin Inhalation. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2024. https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/drug-shortage-detail.aspx?id=953&loginreturnUrl=SSOCheckOnly (accessed March 2024)

- 28Santos RP, Chao J, Nepo AG, et al. The Use of Intravenous Palivizumab for Treatment of Persistent RSV Infection in Children With Leukemia. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e1695–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1768

- 29de Fontbrune FS, Robin M, Porcher R, et al. Palivizumab Treatment of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;45:1019–24. https://doi.org/10.1086/521912

- 30Immunity types. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/immunity-types.htm (accessed March 2024)

- 31Sun M, Lai H, Na F, et al. Monoclonal Antibody for the Prevention of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Infants and Children. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e230023. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.0023

- 32Palivizumab. British National Formulary. 2024. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/palivizumab/ (accessed March 2024)

- 33Beyfortus Summary of Product Characteristics. European Medicines Agency. 2022. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/beyfortus-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 34Battles M, McLellan J. Respiratory syncytial virus entry and how to block it. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:233–45.

- 35Abrysvo powder and solvent for solution for injection. Electronic medicines compendium. 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/files/pil.15309.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 36Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunisation programme for infants and older adults: JCVI full statement, 11 September 2023. Department of Health and Social Care. 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/rsv-immunisation-programme-jcvi-advice-7-june-2023/respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-immunisation-programme-for-infants-and-older-adults-jcvi-full-statement-11-september-2023#programme-to-protect-neonates-and-infa (accessed March 2024)