Science Photo Library / Alamy Stock Photo

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the principles of project management and how they can be applied to clinical trials;

- Identify some of the tools that can be used for research project management;

- Understand the role of the pharmacist in these processes.

Introduction

Research is an integral component of any modern healthcare service that incorporates evidence-based practice, where clinical decisions are made based on available research to ensure balanced and appropriate clinical guidance[1]. The current high standards of medical care are partly attributable to the clinical studies that have been conducted under the guidance and funding of regulatory bodies, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and the UK Medical Research Council. In addition to testing new drugs and devices, clinical trials provide a scientific basis for advising and treating patients, contributing immensely to safe and effective clinical practice.

Pharmacists play a vital role in the clinical trial process. They are often responsible for dispensing medications and ensuring that the study protocol is followed correctly. Additionally, pharmacists can provide valuable input in the design of clinical trials, particularly in areas related to medication dosing and drug interactions[2]. They can also assist with data collection and analysis, which is essential for evaluating the safety and efficacy of new medications.

Applying project management principles to clinical research has the potential to improve efficiency across the research process. This article will outline the five basic phases of project management and show how they can be beneficial to research projects. It will also highlight the role of the pharmacist in clinical research and show how common obstacles to project management approaches can be overcome.

Managing clinical trials

A successful clinical trial requires organisation and the effective execution of activities and tasks, within given timelines and in a step-wise manner, and must be managed meticulously to avoid unnecessary delays and problems. It can be a time-consuming, difficult and challenging task that must be fulfilled with a finite budget, and therefore requires careful planning and organisation from the onset. An analysis of 114 multi-centre clinical trials showed that 45% of trials failed to reach 80% of the pre-specified sample size required to obtain significant data, and around a third were unable to recruit study participants within the time specified and had to extend, costing more time and resources[3].

Box 1: Clinical trial phases

Clinical trials are divided into four phases, each with its own purpose and design.

Phase 1: Trials are the first step in testing a new drug or treatment in humans. They are conducted to evaluate the safety of the drug and determine the appropriate dosage. Typically, phase 1 trials involve a small group of healthy volunteers, who are closely monitored for adverse effects. Phase 1 trials can last several months, and the results are used to inform the design of subsequent trials.

Phase 2: Trials are conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the drug or treatment in a larger group of patients. These trials can last several years and involve hundreds of participants. Phase 2 trials also determine the optimal dosage and any potential side effects.

Phase 3: These trials are the largest and most expensive phase of clinical trials. They are designed to confirm the safety and efficacy of the drug or treatment in a large, diverse population. Phase 3 trials can involve thousands of participants and can last several years. The results of phase 3 trials are used to support an application for approval by regulatory authorities, such as the US Food and Drug Administration.

Phase 4: Trials are conducted after a drug or treatment has been approved by regulatory authorities and is on the market. These trials are designed to monitor the long-term safety and efficacy of the drug or treatment in a larger, more diverse population. Phase 4 trials can also be used to explore new uses for the drug or treatment, or to compare it to other treatments[4].

Applying project management principles to clinical trials

We propose that clinical trials can be conducted more efficiently using project management principles. A project is any temporary endeavour that has a clear beginning and end, clear boundaries and is creating something new that did not previously exist. Large and small clinical trials can be classified as ‘projects’.

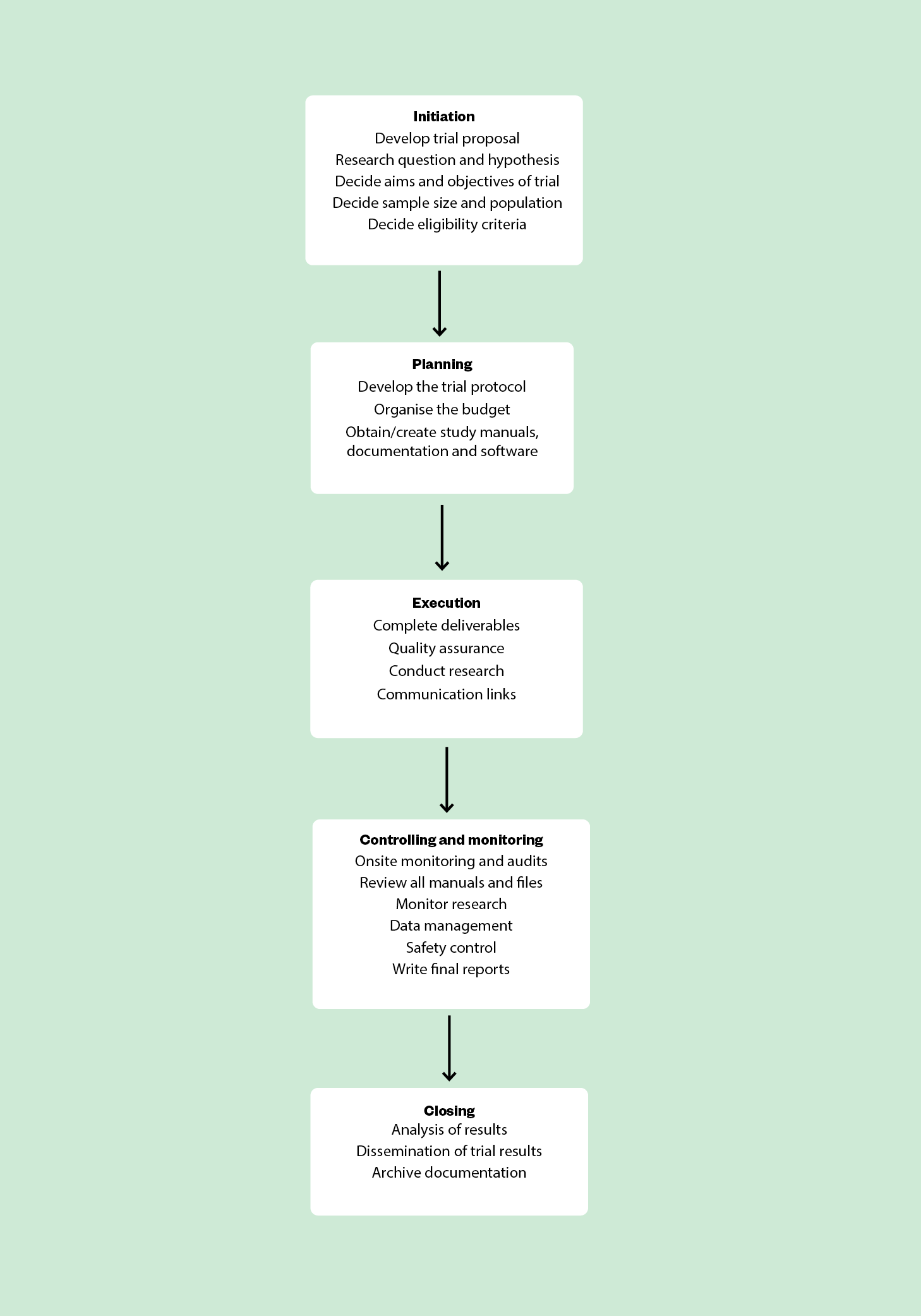

Project management can be described as having five steps:

- Initiation

- Planning

- Executing

- Controlling and monitoring

- Closing[5,6]

These principles were initially developed for engineering and construction-based disciplines, but can easily be applied to academic research projects, pharmaceutical industry work[8] and, in particular, prospective studies, such as clinical trials[7]. By systematically applying the above project management principles, it is possible to eliminate costly mistakes, prevent budget overruns, improve quality and save time[8,9].

There are very few clinical trials that have applied the principles of project management to guide and implement the full process from inception to completion. The Obsessive Compulsive Treatment Efficacy Trial (OCTET), funded by the NIHR, is one of the few studies to also investigate the application of research project management tools to the management of the trial. The purpose of this part of the study was to evaluate whether adoption of the main principles of project management would lead to successful completion and greater satisfaction for the staff involved in the day-to-day operation of the trial. It was concluded that developing trial management and methods was vital to the success of clinical trials[10]. Another example of the successful application of project management principles to a clinical study is the Alcohol and Pregnancy Project[11]. As part of this, the researchers comprehensively endorsed project management and agreed that it contributed substantially to the research outcome[11].

In this article, the main principles of project management will be applied to research projects in health settings, using a clinical trial as an example of a complex project in a multi-centre setting.

Step 1: Initiation

The study proposal is the formal initiation of a clinical trial project. It gives the background for the research project and describes the transformation of the research question/hypothesis into an actual study.

The study proposal should include the following elements:

- What the trial is trying to achieve (i.e. objectives, the study intervention and the differences in treatment sought);

- Sample population;

- Eligibility criteria;

- Study intervention;

- Sample size;

- Differences in the treatment effects that are sought;

- How data will be collected;

- Data collection and analysis according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines;

- How the project will be monitored and controlled to ensure it is delivered on time;

- How the trial results will be reported and disseminated;

- Quality assurance to ensure reliable and reproducible results of the highest standards[6,12,13].

Ethical approval must be sought at this stage and a steering committee set up, chaired by the principal investigator and others who will provide guidance and advice, but not be involved in the implementing of the project on a practical level. Finally, applications must be submitted to a funding organisation, which will give the green light for the next phase of the project.

Step 2: Planning

Formulate a clear project protocol that involves every aspect of the vision and scope of the project, including the day-to-day running of the trial. This is the most important phase of the project, as it allows the researchers and investigators to devise a clear plan on how to manage the process according to the scope of the study, within a designated timeframe and within budget. The major features of this phase of project management are:

- Study protocol;

- Study budget;

- Study manuals, documentation and software.

Study protocol

The study protocol is the plan of how the overall study will be managed by estimating a realistic time schedule of what can be achieved. It allows the investigators and all individuals involved to keep the project on time and within budget. The main features are:

- The timings for grant submission and grant approval;

- Site activation;

- Study participant recruitment;

- Data collection and data analysis;

- Outlining the timing and sequence of each major event within the study;

- The sequence of events required to meet the study objectives;

- Defining the persons responsible for activities and tasks;

- Establishing methods of communication between the steering committee and the independent data safety and monitoring committee.

Study budget

The main features of budgeting and costs for projects are:

- Estimating the budget and cost for each major milestone within the project lifecycle;

- Itemised budget for staff salaries (e.g. researchers, investigators, database programmers, statisticians);

- Site payment for contributing hospitals and study intervention costs;

- Contingency funds if events do not follow the protocol.

Study manuals, documentation and software

Study manuals ensure all staff receive the same training and make it more likely that staff will conduct the study in the same way — this is particularly relevant for clinical trials involving several sites (multi-centre trials). If drugs are being investigated in the study, a pharmacy manual is essential to specify preparation, storage, routes of delivery to the body and destruction. Finally, randomisation of study participants to different treatment arms in a confidential manner requires the use of software systems, which must be acquired and established.

Documentation relating to all aspects of the clinical trial is essential and should be recorded, monitored and archived in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines[13,14]. GCP is a quality standard for designing, conducting, recording and reporting trials that involve the participation of human subjects. Compliance with this standard provides public assurance that the clinical trial data are credible. Source documentation includes the clinical history and medical records of all study participants before, during, and after the trial ends, records relating to staff training, handling of all drugs used, standard operating procedures, laboratory reports etc. This will ensure safety of study participants, accountability, and high-quality results. An audit in 2010 by the US Food and Drug Administration found that 6 out of 10 clinical trials did not keep adequate documentation[14].

Step 3: Execution

At the execution stage of a project, the study plan is implemented and the clinical trial commences. The main features of this phase are:

- Teams are acquired and developed;

- Allocation of resources and support is provided to team members to ensure that assigned tasks are completed;

- Quality assurance is performed (see Step 4);

- Deliverables are developed and completed to meet the project’s aims and objectives;

- Communication links are established with the clinical teams and stakeholders (e.g. pharmaceutical companies, funders, regulatory agencies, study participants, research institutions);

- Research is conducted (e.g. analysing samples, synthesising and analysing data);

- Educational resources are disseminated to healthcare professionals, stakeholders and the general public[9,15,16].

Step 4: Controlling and monitoring

This process occurs alongside the execution phase, focusing on measuring project progression and performance in line with previously agreed goals and timelines. The project plan specifies the quality assurance, control, monitoring and risk assessment of activities conducted while the clinical study is in progress. This includes, but is not limited to:

- Onsite monitoring and audits (e.g. looking through medical records and cross-checking data against case report forms);

- Reviewing the study manuals and files to ensure essential documents are up to date;

- Reviewing all manuals, including staff training manuals and standard operating procedures;

- Making sure research is conducted in accordance with GCP and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency for research with human participants;

- Regularly reviewing the tasks and activities associated with each milestone;

- Data management (e.g. data checking, ensuring the data is void of errors);

- Interim data analysis;

- Safety monitoring[13,17].

The outcomes of control and monitoring are compared to the original study plan and adjustments can be made if necessary.

A good clinical trial will have a contingency plan in place that was developed before the execution phase. It will specify the possible risks, the likelihood of them occurring, the potential impact on the project and the course of action recommended should they occur.

Step 5: Closing

Towards the end of a research project, the main activities involve:

- Final analysis of the data;

- Reporting of the data (e.g. presentations or a manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal);

- Closing of study sites;

- Informing ethics committee and trial staff of completion;

- Submitting final reports to funding bodies;

- Informing study participants of the completion of the clinical trial and the outcomes;

- Archiving records in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use’s good clinical practice guidelines, which state that all documentation should be kept for at least three years after completion of the clinical trial[13].

In addition, a post-trial review might be conducted, in which management of the clinical trial is evaluated to determine strengths and weaknesses in the process, so that future clinical trials can be conducted more effectively[16].

Role of the pharmacist in clinical trials

Pharmacists play a crucial role in clinical trial management, particularly in the areas of drug preparation, dispensing and management of adverse drug reactions. They are responsible for ensuring that the investigational drug is properly handled and administered to trial participants, and that any adverse events or drug interactions are documented and reported appropriately.

According to the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, pharmacists’ expertise is useful in the planning and conduct of clinical trials, particularly in the following areas:

- Investigational medicinal product management: preparation, labelling, storage, temperature monitoring, dispensing and accountability. This includes ensuring that the drug is handled and stored in accordance with the trial protocol and applicable regulations;

- Drug safety: monitoring trial participants for any adverse drug reactions or interactions and reporting these events to the study team and regulatory authorities;

- Compliance monitoring: pharmacists can help ensure that trial participants comply with the dosing regimen and other requirements of the trial protocol, and provide education and counselling as needed to ensure proper adherence;

- Quality control: general check of documentation, including informed consent forms and other legal documents;

- Data management: pharmacists are responsible for maintaining accurate records of drug dispensing and adverse event reporting, and for ensuring that these records are kept confidential and secure.

The success and failure of clinical trials

There are many challenges associated with managing clinical research projects. One of the main problems encountered in clinical trials, which has been cited repeatedly, is the difficulty of registering a sufficient sample size of patients in a timely fashion[18,19]. Trials that did manage to recruit successfully were more likely to have a dedicated trial manager[20]. Another challenge in multi-centre studies is identifying appropriate clinical sites and having realistic recruitment expectations. However, the main challenge is implementing and maintaining effective management systems and techniques in response to the needs of the project.

Box 2: Top tips to overcome the challenges of project management

- Define project scope: clearly define the scope of your project, including the goals, objectives and deliverables;

- Develop a project timeline: create a detailed project timeline that outlines milestones and deadlines for your project;

- Communicate regularly: establish regular communication channels with all stakeholders involved in the project, including team members, sponsors and other relevant parties;

- Monitor project risks: identify potential risks to the project and develop contingency plans to address them;

- Use project management tools: consider using tools such as Gantt charts, project management software and risk management tools.

Project management in health and medical research can substantially benefit both the managerial and scientific aspects of clinical trial projects. Project management may also reduce a proportion of fund waste[21]. Staff that were part of the Alcohol and Pregnancy Project found that project management strategies improved communication and the integration of project work across multiple organisations and professions; helped them clarify and agree goals; assisted the delivery of defined project outcomes; and helped ensure accountability for results and performance[10]. Although this article has focused on the application of project management principles to clinical trials, these principles can be applied to any pharmacy project, whether research-related or not; for instance, clinical audits and quality improvement initiatives.

By using project management principles, pharmacists can ensure that their projects are completed on time, within budget and to the desired quality standards. In addition, using these principles allows pharmacists to enhance the quality and impact of their own projects, ultimately improving patient care and healthcare outcomes.

- 1Kristensen N, Nymann C, Konradsen H. Implementing research results in clinical practice- the experiences of healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;16. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1292-y

- 2Brown J, Britnell S, Stivers A, et al. Medication Safety in Clinical Trials: Role of the Pharmacist in Optimizing Practice, Collaboration, and Education to Reduce Errors. Yale J Biol Med 2017;90:125–33.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28356900

- 3Francis D, Roberts I, Elbourne DR, et al. Marketing and clinical trials: a case study. Trials. 2007;8. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-8-37

- 4Evans SR. Fundamentals of clinical trial design. Journal of Experimental Stroke and Translational Medicine. 2010;3:19–27. doi:10.6030/1939-067x-3.1.19

- 5Farrell B, Kenyon S, Shakur H. Managing clinical trials. Trials. 2010;11. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-11-78

- 6A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge. 7th ed. Project Management Institute 2021.

- 7Notargiacomo Mustaro P, Rossi R. Project Management Principles Applied in Academic Research Projects. IISIT. 2013;10:325–40. doi:10.28945/1814

- 8Overgaard PM. Get the keys to successful project management. Nursing Management. 2010;41:53–4. doi:10.1097/01.numa.0000381744.25529.e8

- 9Payne JM, France KE, Henley N, et al. Researchers’ experience with project management in health and medical research: Results from a post-project review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-424

- 10Arundel C, Gellatly J. Learning from OCTET – exploring the acceptability of clinical trials management methods. Trials. 2018;19. doi:10.1186/s13063-018-2765-6

- 11Huljenic D, Desic S, Matijasevic M. Project management in research projects. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Telecommunications, 2005. ConTEL 2005. 2005. doi:10.1109/contel.2005.185981

- 12The Guide to Efficient Trial Management. UK Trial Managers’ Network. 2020.https://www.tmn.ac.uk/resources/34-the-guide-to-efficient-trial-management (accessed Apr 2023).

- 13E6(R2) Good Clinical Practice: Integrated Addendum to ICH E6(R1). US Food and Drug Administration. 2018.https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/e6r2-good-clinical-practice-integrated-addendum-ich-e6r1 (accessed Apr 2023).

- 14Bargaje C. Good documentation practice in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2:59. doi:10.4103/2229-3485.80368

- 15Clinical Trial Protocol Execution within a Clinical Research Organisation. BioPharma Services. 2021.https://www.biopharmaservices.com/blog/clinical-trial-protocol-execution-within-a-clinical-research-organization-cro/ (accessed Apr 2023).

- 16McCaskell DS, Molloy AJ, Childerhose L, et al. Project management lessons learned from the multicentre CYCLE pilot randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3634-7

- 17Good clinical practice for clinical trials. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2023.https://www.gov.uk/guidance/good-clinical-practice-for-clinical-trials (accessed Apr 2023).

- 18Goodarzynejad H, Babamahmoodi A. Project Management of Randomized Clinical Trials: A Narrative Review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17. doi:10.5812/ircmj.11602

- 19Fogel DB. Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: A review. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications. 2018;11:156–64. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2018.08.001

- 20Campbell M, Snowdon C, Francis D, et al. Recruitment to randomised trials: strategies for trial enrolment and participation study. The STEPS study. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11. doi:10.3310/hta11480

- 21Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, et al. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Sci. 2007;2. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-2-40