“I grew up just thinking blisters were a part of everyday life,” says Jessica Skeith.

“My parents would always get me the expensive school shoes hoping that they wouldn’t give me blisters, but I always got them no matter what.”

Skeith, aged 29 years, has epidermolysis bullosa (EB), a group of rare genetic skin disorders that cause patients to have extremely fragile skin that blisters and tears from even the slightest touch. As the skin is so fragile, it is often termed ‘butterfly skin’, in reference to the fragility of a butterfly’s wings.

On her 17th birthday, Skeith climbed Mount Kilimanjaro while on a college trip to Tanzania. “Every step on the way up was fine, but coming back down I realised blisters had formed. I’d worn the shoes many times before but, because of the heat and friction, I got blisters and pressure sores.

“I had to be on crutches when I got home because they were infected and so they could heal properly, which then meant I got blisters on my hands. It was like a never-ending cycle of blisters.”

EB is currently incurable and is thought to affect around 5,000 people in the UK and 500,000 people worldwide1. Patients are commonly diagnosed as babies and young children, with symptoms often presenting from birth, but the condition can also emerge in adulthood.

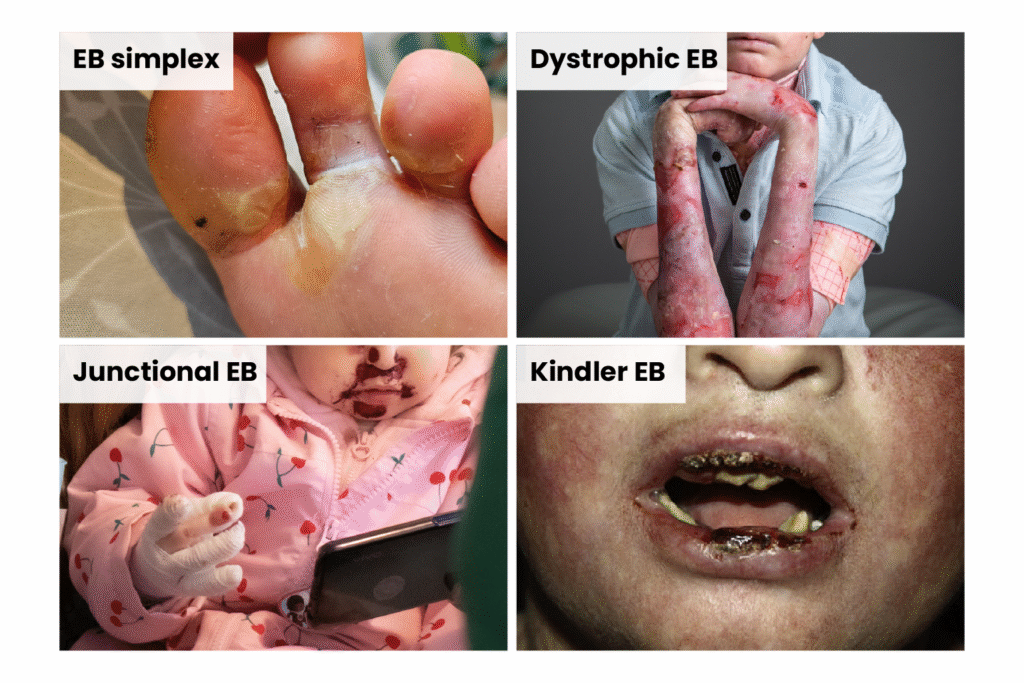

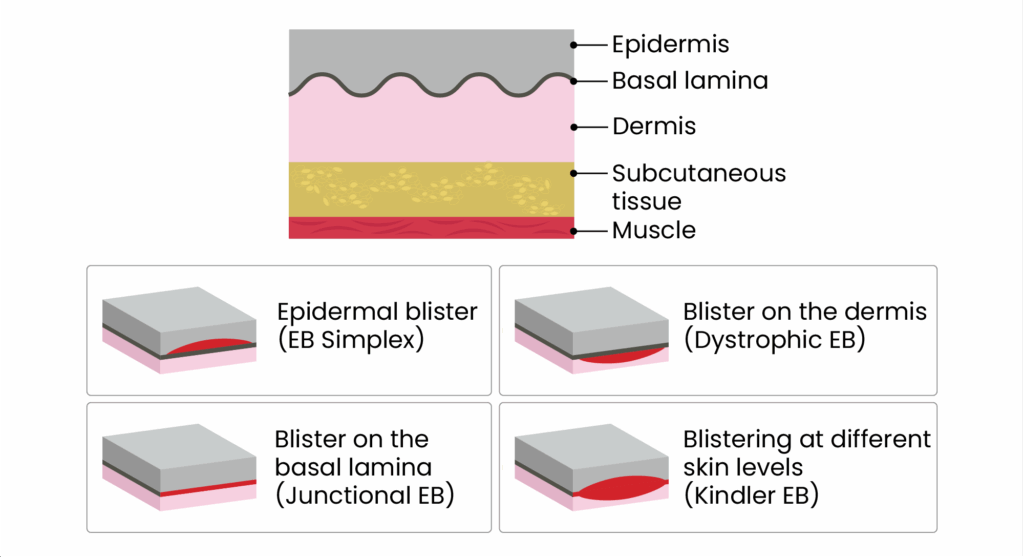

There are four main types of EB: EB simplex, dystrophic EB, junctional EB and Kindler EB, with more than 30 subtypes (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Images of the four main types of epidermolysis bullosa

Figure 2: The layer of skin each type of epidermolysis bullosa affects

There are a range of symptoms, but most common across all types of EB is painful and itchy skin with blisters (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Symptoms of epidermolysis bullosa

Management of the condition includes daily skin and wound care, such as applying protective dressings and lancing blisters, along with preventing trauma to the skin — for example, avoiding the armpits when lifting babies.

But there may be hope on the horizon. Stem cell and gene therapy technologies are under development to provide correction of the genetic defect in EB at a DNA or mRNA level.

In the UK, the topical treatment Filsuvez (birch bark extract; Chiesi) was approved in 2023 by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to treat wounds in junctional EB. Meanwhile, topical gene therapy Vyjuvek (beremagene geperpavec; Krystal Biotech) — used for wound management in dystrophic EB — is currently undergoing NICE appraisal, with a decision expected in July 2026.

In April 2025, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first autologous gene-edited cell therapy, Zevaskyn (prademagene zamikeracel; Abeona Therapeutics), for recessive dystrophic EB. The treatment involves grafting gene-corrected skin onto open wounds.

[Some patients have] said [anti-inflammatory drugs have] completely changed their lives. Their wounds are a lot better, less pain, less breakage, mental health is a lot better

Sagair Hussain, director of research at the EB charity DEBRA

Trials are currently underway that are seeking to repurpose drugs used for other conditions to improve management of EB.

“We’ve got some initial proof of concept where some anti-inflammatory drugs actually work with EB patients,” says Sagair Hussain, director of research at the EB charity DEBRA.

“When I say ‘work’, I mean because they’re damping down the inflammation. You’ve got much better wound closure, you’ve got less pain, you’ve got less breakage — so quality of life is so much better.

“We’re currently funding two active clinical trials. One is to repurpose a drug called apremilast, which is licensed for psoriasis, and that’s in France, and then we’ve got another one to repurpose dupilumab, which is licensed for severe eczema, and that’s in Chicago, [Illinois].”

Hussain says he has already spoken to some patients with EB who are participating in the trials. “They’ve just said it completely changed their lives. Their wounds are a lot better, less pain, less breakage, mental health is a lot better.”

He is equally excited about a trial that DEBRA signed off in November 2025, in partnership with rare diseases charity LifeArc, called ‘Advancing repurposed therapeutics for epidermolysis bullosa’ (ART-EB).

“This is the world’s largest drug repurposing platform for EB, where we’re going to try to test three drugs at any one time. The reason why we’re testing three drugs is patient numbers. Because EB is a rare condition, we can’t get enough patients to do more trials.”

“A big challenge for us is what happens next?,” he notes. “How do we get the drug approved on the NHS?”

“One of the challenges you get with rare disease is that, from a company’s point of view, patient numbers are so small that, commercially, it makes no sense to submit another licence for their drug because the cost of submitting the licence, plus the cost of post-authorisation safety studies, outweighs the commercial benefit.”

According to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), around 3.5 million people in the UK are affected by a rare disease, but only 5% of rare diseases have an approved treatment2.

In November 2025, the medicines regulator announced that it would overhaul the rulebook for rare diseases, making it easier to get therapies tested, manufactured and approved in the UK, in line with the government’s ‘Rare disease action plan’2,3.

Figure 4: Epidermolysis bullosa trial protocols

Repurposing dupilumab

One of the trials funded by DEBRA is looking at repurposing the eczema drug dupilumab to treat itch in patients with all EB types. It has been running in Chicago, Illinois, since 2023 and has enrolled almost 50 people.

Trial lead Amy Paller, a paediatric dermatologist and professor of dermatology at Northwestern University in Illinois, says dupilumab was chosen owing to its success in treating itch in atopic dermatitis and eczema in patients as young as six months.

“There is work from itch experts suggesting there may be some independent effect on itch, regardless of mechanism, so we thought that it might be good to try to see if we could repurpose it for our patients with EB who, across the board, are very often quite itchy.

“Of course, the last thing you want to do is scratch your skin, as you might get a blister there,” she adds.

Dupilumab was like a magic bullet in terms of reducing that itch that causes so much blistering, particularly on the extremities with scarring

Amy Paller, a paediatric dermatologist and professor of dermatology at Northwestern University in Illinois

As a result, the study is also examining whether the drug can reduce the risk of skin infections from scratching, as well as whether it can improve sleep by stopping patients scratching during the night.

Participants, who travel from all over the United States, are given dupilumab via subcutaneous injection every two to four weeks, with the dose and frequency depending on their age and weight.

Paller says that findings for the first 12 patients showed that dupilumab had been “very helpful”.

“Dupilumab was like a magic bullet in terms of reducing that itch that causes so much blistering, particularly on the extremities with scarring.

“We were able to maintain evidence of a significant reduction in itch in the majority of our patients,” she says, with the drug having an effect on all subtypes of EB, apart from a subtype of junctional EB related to a deficiency of collagen 17.

The trial is observing itch intensity through the use of a ‘worst itch’ scale, where patients rank their itch when at its worst in a 24-hour period — with 0 being ‘no itch’ and 10 being the ‘worst imaginable itch’ — along with the use of a mechano-acoustic sensor worn on the hand to measure night-time itch while patients sleep.

“It measures by the sound of itch or pat,” explains Paller. “Because these kids don’t just scratch, they sometimes pat to try to relieve the itch.

“What we found, which was very interesting, is that some people are not even aware of what they’re doing while they’re sleeping.

“One teenager was scratching a lot at night — much more than she was aware of during the day, when she obviously was controlling things — and that plummeted with the medication, as did her blisters.”

Paller notes that it has been easier to recruit patients with EB to the trial than to treat those with atopic eczema. “It’s an interesting phenomenon, because it’s such a big deal for many families to get this shot when the children have atopic eczema, but when they have EB and their lives are just full of pain, it doesn’t seem to faze them.”

Repurposing apremilast

Another trial in its early stages is running across four centres in France, looking at repurposing the psoriasis drug apremilast for the treatment of EB simplex in adults and children. The trial began at the end of 2024.

Participants take tablets twice a day for eight weeks, stop for four weeks and then take the tablets again for a further eight weeks. The trial will assess the impact of the drug on blistering, pain, itch and quality of life.

Apremilast has been selected because of its effects on inflammation. “EB is a genetic disease, but it has all the markers of an inflammatory disease, such as psoriasis or eczema,” explains trial lead Christine Chiaverini, a dermatologist at Nice University Hospital in France.

“We did a study a few years ago to understand which kind of inflammation [is involved in EB] and found that the TH17 pathway is involved.”

The TH17 pathway is also involved in psoriasis. Under the pathway, TH17 cells produce cytokines that promote skin inflammation, which apremilast inhibits.

The trial currently involves three participants; there were originally five but one patient dropped out owing to gastrointestinal disturbance, a known side effect of apremilast, while another patient stopped treatment after losing too much weight.

Chiaverini says things are going well for the other patients. “One patient told me that she could go to do the shopping with her mother. It was the first time for her without blisters on her feet, so she was very happy.”

Another has been able to go to summer camp. “She has been able to walk and swim and have a beautiful holiday,” Chiaverini says.

Chiaverini adds it has been difficult to recruit more participants owing to the seasonality of symptoms. “We started in June or July [2025]. It was a good time because patients have more blisters.

“Some patients don’t have enough blisters at the moment because it has been September, October etc. and in the north of France, it’s already cold, so it’s been difficult to reach the inclusion criteria.”

She says there are five more patients planned to join the trial in spring 2026, and that the study should reach its objective of 20 participants once a research centre in Paris has been set up.

It is possible that patients could opt to take the medication only during the period of the year they find most difficult, which is likely summer, Chiaverini explains.

While this is great news, “there’s only three patients” in the trial currently, she notes, adding that it’s “very difficult” to recruit patients to the study owing to low patient numbers.

Advancing repurposed therapeutics

The first-of-its-kind ‘ART-EB’ trial will test three drugs — repurposed from their use in psoriasis — at the same time for EB simplex, junctional and dystrophic.

“There are psoriasis immune signals in the blood and skin of adults with EB across three of the four main EB types. And based on that, I propose to repurpose the available biologics from psoriasis … to block the immune signals IL 17 and IL 23,” explains trial lead Su Lwin, senior research fellow at King’s College London and a consultant dermatologist.

The trial will be the first to immune profile patients before selecting which drug to use to personalise the treatment. An added niche is that drugs that are not working will be dropped from the trial early on and replaced with another.

The trial is yet to begin, but Lwin is excited for its potential.

“I wanted to move away from the traditional approach of testing one drug in one clinical trial. It’s slow, expensive and places a heavy burden on everyone involved.

“I want to be able to test multiple drugs in the same trial setting and also to drop the treatment early on. Too often, patients are asked to stay on a treatment for six months, or even a year, despite early signs it may not be helping.

“That’s a waste of money and also [time] for the patients. But this is the trial that allows that flexibility to drop treatments as needed. So, even though, in the short run, it’s a bit more expensive to set it up, in the long run, it will be sustainable and cost effective.”

She says that, even for patients with eczema and psoriasis, while there are more than a dozen biologics available, patients’ immune systems are not profiled before they begin taking them, “so it’s a bit of trial and error”.

An advisory group from NICE will provide advice on the project, “so that at the end of the trial, we have a clear idea of how the drugs proven to be effective for EB can be made available for use in clinics”, says Lwin.

“The ambition is to redefine this genetic condition in immunological terms, enabling more personalised treatments for EB,” she adds.

“My goal is that ART-EB will also provide a blueprint for how other rare diseases can be studied and treated.”

Is a cure on the horizon?

With the research into management options sounding promising, it begs the question: are we close to having a cure for EB?

“That’s my vision,” says Lwin. “But it’s not going to be in the next five years.”

She says that while there is ongoing research into stem cell and gene therapies, trials tend to get stuck at early phases, which may be down to a convoluted process of getting drugs into trials and a lack of expertise in the area.

It’s not just about the science and the technology. It’s about all of that red tape, so to speak

Su Lwin, senior research fellow at King’s College London and a consultant dermatologist

“There’s preclinical animal testing, and then the early phase human [trials], and then late phase human [trials] and then market access.”

She notes that, in EB, “a lot of people don’t have market access to all of the intellectual property” for potential treatments.

“Unless that is streamlined, we cannot find a cure. It’s not just about the science and the technology. It’s about all of that red tape, so to speak.”

For EB simplex, Chiaverini says that apremilast may be the first treatment “and then we may find another treatment that’s more efficient”.

For other types of EB, combination treatment may represent the best cure, she says.

“For example, genetic treatment, topical and also anti-inflammatory treatments,” she says. “A mix of all these kind of treatments could cure our patients”, or at least “strongly improve their symptoms and quality of life”.

Paller is also hopeful. “A lot of great research is being done right now,” she says.

She refers to Zevaskyn as the “first step” towards a cure.

“We’re far from a cure in the sense of a magic wand, but it’s the first step, and if we can’t take the first step, we can’t get there,” she adds.

“I think it’s just the start, but I’m so excited, because if we don’t have industry interested in creating products, if we don’t have people interested in trying to repurpose what’s out there, we’re never going to be able to help these children and adult survivors.”

“It may take a few decades,” she says. “But ultimately, yes, we will get to that cure.”

- 1.DEBRA UK Research Impact Report 2021. DEBRA. 2021. Accessed January 2026. https://www.debra.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/debra-research-impact-report-2021.pdf

- 2.Rare therapies and UK regulatory considerations. MHRA. November 2025. Accessed January 2026. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/rare-therapies-and-uk-regulatory-considerations/rare-therapies-and-uk-regulatory-considerations

- 3.England Rare Diseases Action Plan 2025: main report. Department of Health and Social Care. February 2025. Accessed January 2026. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/england-rare-diseases-action-plan-2025/england-rare-diseases-action-plan-2025-main-report