Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Recognise the symptoms of haemorrhoids and when referral is needed;

- Understand the pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment options available, including any advice relating to self-care and prevention;

- Know how to advise patients on the rectal application of creams/ointments and suppositories;

- Understand that there are different presentations of haemorrhoids.

Haemorrhoids are clusters of vascular tissue, smooth muscle and connective tissue arranged in three columns along the anal canal[1]. In healthy individuals, they act as cushions that help maintain continence[1]. Although haemorrhoids — or ‘piles’ as they are otherwise commonly known — are normal structures, the term has become synonymous with them in an abnormally swollen and symptomatic state[2]. This happens when the venous drainage of the anus is altered, causing the venous plexus (a congregation of multiple veins) and connecting tissue to dilate, creating an outgrowth from the rectal wall[3].

The exact prevalence of haemorrhoids is unknown because many patients are asymptomatic and do not seek medical attention[3]. A US colorectal cancer screening study found a 39% prevalence of haemorrhoids, with 55% of those patients reporting no symptoms[3]. Community-based UK studies have reported that haemorrhoids affect 13–36% of the general population, although this estimate may be higher than the actual prevalence owing to self-reporting and the incorrect attribution of anorectal symptoms to haemorrhoids, such as pain and bleeding[1,2].

NHS signposting for common clinical conditions and minor ailments encourages patients to seek prompt clinical advice and treatment from their local pharmacy. Therefore, acute or chronic presentations of haemorrhoids may frequently be seen in community pharmacies[4] and it is important that pharmacists can provide patients with the appropriate guidance and information for management.

Risk factors

The aetiology of haemorrhoids is currently speculative; however, this may change as large-scale studies are in progress to investigate the genetic causes[5]. Although unproven, a low-fibre diet and constipation have historically been thought to be risk factors[1]. Other proposed risk factors include:

- Age — there is higher prevalence in persons aged 45–65 years;

- Socioeconomic status — there is higher prevalence with higher socioeconomic status, although this may reflect differences in health-seeking behaviour rather than true prevalence;

- Pregnancy;

- Heavy lifting;

- Chronic cough;

- Certain toilet behaviours, such as straining or spending more time on a seated toilet than on a squat toilet; squatting provides a better angle for defecation[1–7].

Diagnosis

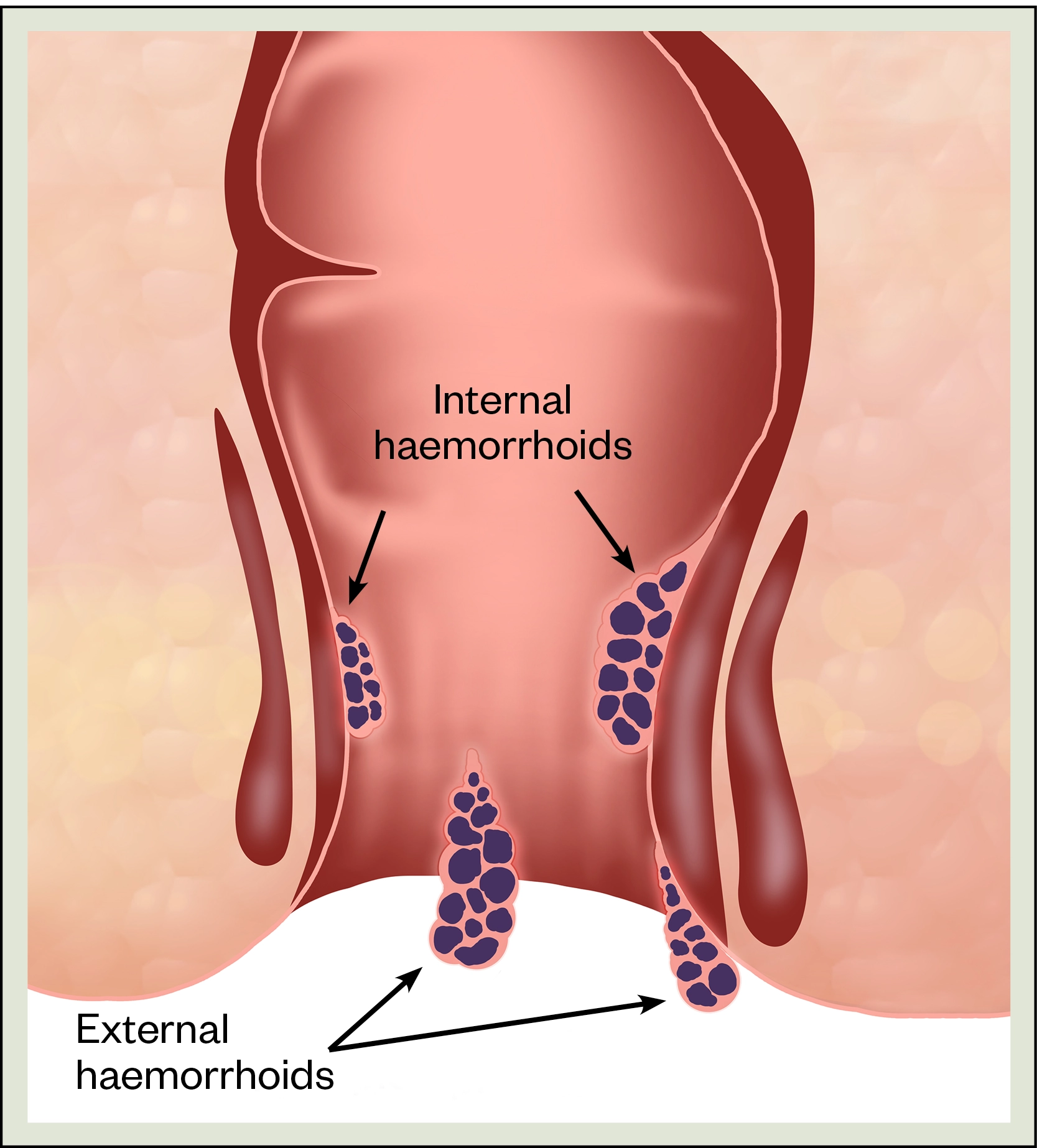

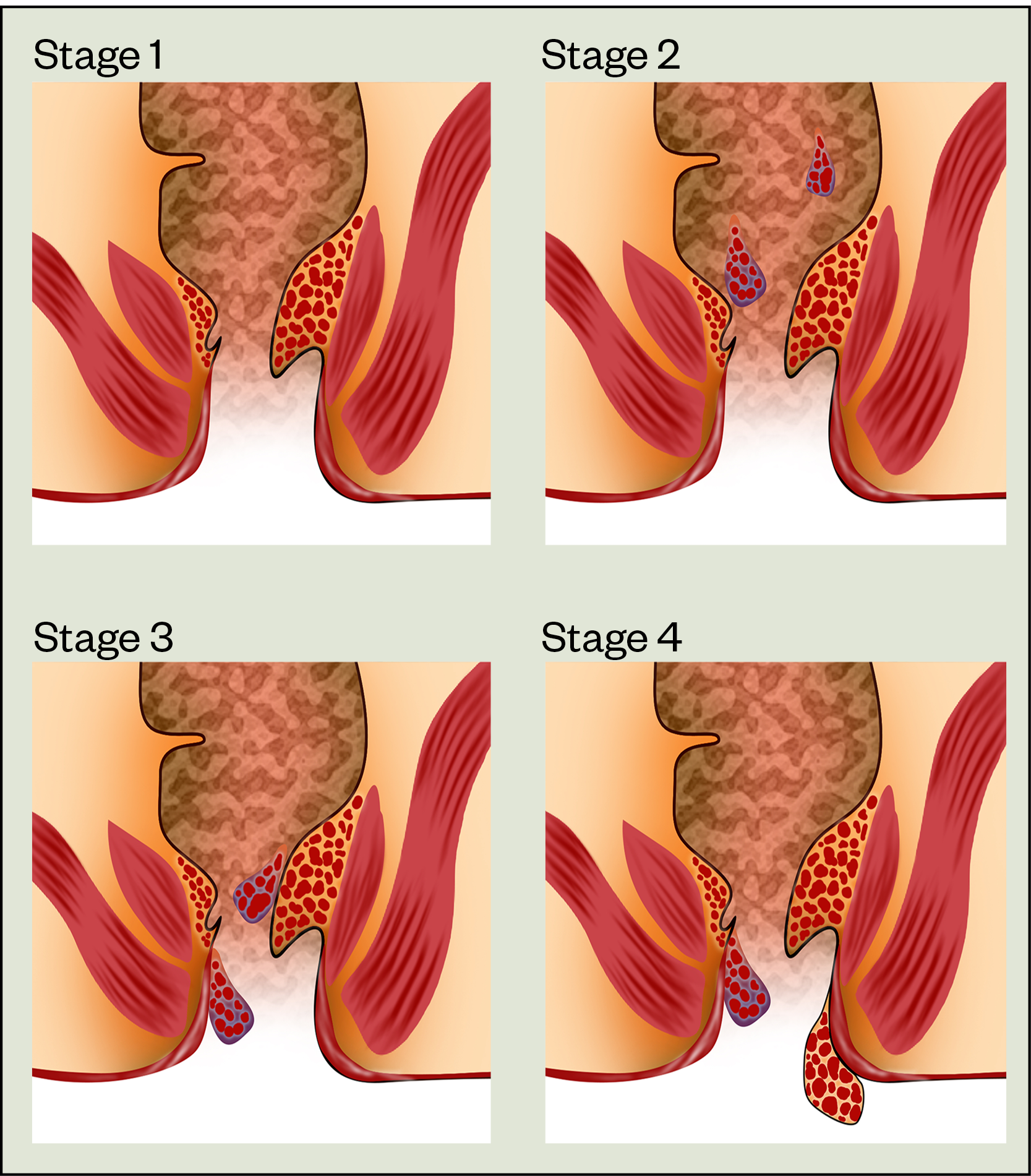

Haemorrhoids are classified as external or internal depending on their position in relation to the dentate line (dividing the upper two-thirds from the lower third of the anal canal). External haemorrhoids originate below the dentate line and are covered by modified squamous epithelium, which is richly innervated with pain fibres (see Figure 1). Internal haemorrhoids arise above the dentate line and are covered by columnar epithelium, which have no pain fibres. Internal haemorrhoids are graded by degree of prolapse using Goligher staging, although classification does not always reflect the severity of the symptoms (see Figure 2)[8]. Internal and external haemorrhoids can be present at the same time[1,2].

Shutterstock.com

Shutterstock.com

Signs and symptoms

External haemorrhoids are often described as lumps and bumps around the anus with itching. The latter is a result of irritation from faecal matter not being fully removed upon wiping[9]. Pain is uncommon unless very severely swollen owing to thrombosis[10].

Symptoms of internal haemorrhoids will commonly include a feeling of discomfort and a sensation of fullness in the rectum or incomplete evacuation, especially after passing stools. Further straining should be avoided to prevent haemorrhoids from prolapsing[10]. Prolapsed haemorrhoids may become itchy and irritated owing to the presence of moisture, mucus and faecal matter. Pain is not usually reported with internal haemorrhoids unless the haemorrhoid is prolapsed and strangulated; the latter occurring when the blood supply has been cut off by pressure applied from the anal muscles[2,10].

Where bleeding is present, this will typically occur after bowel motions because of the microtrauma of passing hard stools. As this is arterial blood, it will usually be bright red in colour and may appear as streaks on toilet paper when wiping, on the surface of stools, or in the toilet water[2,10]. GP referral to exclude other diagnoses should be made if the blood has a different appearance, such as darker red, brown or black, or is mixed with the stool. These signs suggest a more proximal blood source and may be a ‘red flag’ cancer symptom[11,12]. Please see Box 1 for example questions that pharmacists can ask to assess symptoms.

Box 1: Example questions that pharmacists may ask as part of symptom assessment

- “Can you describe to me your current symptoms and when you first noticed them?”

- “Do you feel the symptoms are getting worse, better or staying about the same?”

- “Have you had these sorts of symptoms before, or is this the first time you’ve felt like this?”

- “Aside from the discomfort around your back passage, how do you feel in general? Are you eating OK? Have you had any digestive problems recently, lost any weight or noticed any bleeding?”

- “Have you already tried any medicines to help relieve these symptoms?” or “If you’ve felt like this before were there any treatments you tried previously that helped?”

Pharmacists have a duty of care to refer patients who present with ‘red flag’ symptoms, but where the bleeding is mild and localised, and in the absence of other red flags (see Figure 3[2,12–14]), treatment initiation with appropriate safety-netting advice and follow up guidance may be appropriate[12].

![Figure 3: Red flags for prompt referral[2,12–14]](https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Figure-3-Red-flags-for-prompt-referral.png)

Thorough history taking will help the pharmacist to exclude other potential causes or alternative diagnoses. See Box 2 for a list of differential diagnoses.

Box 2: Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses of haemorrhoids include:

- Adenomatous polyps;

- Anal fissure;

- Anal or colorectal cancer;

- Anorectal fistula;

- Condylomata acuminata (warts);

- Diverticular disease;

- Inflammatory bowel disease;

- Perianal abscess;

- Portal hypertension;

- Pruritus ani and associated causes;

- Rectal prolapse;

- Sexually transmitted infections (e.g. gonorrhoea, syphilis or chancroid)[2].

Complications

Pharmacists should advise surveillance of the affected area in case dermatological complications develop. The skin may become macerated owing to mucus discharge, ulcerated owing to thrombosed external haemorrhoids, or irritated, secondary to skin tags[2]. Changes that suggest signs of infection or of skin breakdown should be referred for review.

A drop in haemogloblin may be detected when there is significant or continuous rectal bleeding. Signs and symptoms of anaemia may include fatigue, breathlessness or pale skin. Pharmacists should refer this to be managed by the GP who will confirm the diagnosis using a blood test[2,15].

For some complications, such as incarcerated or thrombosed haemorrhoids, surgical intervention may be indicated to resolve symptoms and promote quicker healing. Referral for surgical correction or dilation may also be indicated where a narrowing of the anal canal, also known as anal stenosis, has developed over time[2,8].

In more serious cases where infection has developed in the area, there is the risk of pelvic sepsis. All cases of suspected sepsis need urgent hospital referral to ensure first doses of antibiotics are administered in-line with antimicrobial policies[2,16].

Complications of haemorrhoids can negatively affect quality of life and so appropriate signposting and advice should be given when making recommendations to ensure timely and appropriate escalation of management.

Treatment and management

In the absence of complications, haemorrhoids are self-limiting and typically heal within a week[7]. Where they are associated with pain, itching or discomfort, pharmacists may offer pharmacological treatment to promote healing and to alleviate symptoms[6]. Pharmacists should be prepared to offer lifestyle advice to aid healing and prevent recurrence.

Pharmacological management

The treatment of haemorrhoids in the community and primary care setting is usually limited to topical preparations that contain combinations of astringents, local anaesthetics and corticosteroids[10]. There is currently no evidence to suggest any one topical preparation is more effective than another. Simple analgesia may also be recommended for pain relief, although non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be avoided in the presence of rectal bleeding[6,7,17].

Pharmacists should recommend onward referral to a GP if self-treatment with a non-prescription product does not improve symptoms within the first seven days of use. This is the typical treatment duration guidance issued in the product licenses for over-the-counter preparations[6]. Advice to avoid prolonged use of topical preparations also reflects the potential for ingredients to cause problematic effects if used over extended periods. For example, prolonged use of topical corticosteroids may cause skin atrophy, sensitisation and contact dermatitis, while extended use of topical local anaesthetics is associated with skin sensitisation[6,17]. Side effects are rare and usually limited to minor irritations for short courses of treatment.

Creams and ointments are usually the products of choice for external haemorrhoids and are typically applied morning and evening. They can also be applied after passing stools when symptoms often flare, using a clean finger or gauze dressing.

Suppositories are usually the best choice for internal haemorrhoids, although some topical preparations come packaged with an applicator that will apply the product into the anal passage. Suppositories can be inserted morning and evening and after passing stools. Pharmacy staff should counsel on the best ways to insert suppositories[18]. Practical advice on the insertion of rectal formulations is available in Box 1 of this article.

For patients with external and internal haemorrhoids, a suppository and topical product can be used at the same time. Information regarding counselling on suppository use can be found here.

Self-care and prevention

Self-care recommendations should be made to support the relief of symptoms and the healing process. This may include the use of a cold compresses to shrink the haemorrhoids, warm baths to soothe the area and the promotion of certain behaviours[2,7,17,19]. Adoption of the following behaviours may promote healing and help to prevent repeated episodes:

- A balanced diet with enough fibre (25-30g daily via high fibre foods or commercial supplements);

- Adequate fluid intake;

- Regular physical activity;

- Maintain stools that are soft and easy to pass;

- Avoid constipation and straining;

- Toilet behaviours, such as going as soon as you need and avoiding sitting on the toilet for long periods;

- Anal hygiene, such as moist, gentle cleaning following a bowel movement;

- Keeping a healthy weight[2,7,17,19].

If dispensing or recommending a medication that can cause constipation, pharmacists should be prepared to give appropriate counselling advice that encourages a normal bowel frequency to be maintained[6]. This should be a frequency that is ‘normal’ for the patient.

Minimally invasive and surgical management

Referral to secondary care for consideration of further management may be indicated depending on the severity of symptoms and degree of prolapse. This will usually be for haemorrhoids that have failed to respond to or have recurred despite conservative management, are graded II–IV, or where the haemorrhoid is incarcerated or thrombosed[20–22].

Incarcerated haemorrhoids are short-term complications that present as severe pain and irreducible prolapsing haemorrhoidal tissue. A referral for surgical intervention is indicated to manage these[19,20].

Surgical intervention may also be indicated for patients who present early with severe symptoms of thrombosis, as this may lead to a quicker resolution of symptoms[22]. However, most patients with thrombosed haemorrhoids can be managed conservatively at home using analgesia, ice packs and stool softeners, with a topical calcium antagonist if required as an adjunct for pain relief. These should be given in combination with advice to avoid straining and constipation[8].

Most minimally invasive (i.e. non-surgical) or surgical procedures will be performed as day cases[7].

Case 1: Pregnancy

A 30-year-old woman presents at her pharmacy seeking advice on managing suspected piles. She explains to the assistant that she is six months’ pregnant and is referred to the pharmacist in the consultation room.

Consultation

The patient explains that she has noticed a small lump around her back passage and has seen some bright red streaks of blood on toilet paper when wiping after defecation. It is quite tender but not painful. She describes no change in bowel habit but may be straining slightly when passing stools.

Diagnosis and advice

The pharmacist highlights that the symptoms are typical of haemorrhoids and a non-prescription treatment can be recommended. A simple, soothing product containing astringents in ointment form would be a safe, suitable option[17]. The patient is given a leaflet from the UK Teratology Information Service’s ‘bumps’ website for additional reassurance regarding the safe treatment of haemorrhoids and its common occurrence in pregnancy[23]. She is advised to see her GP if her symptoms worsen or do not resolve in the next few days.

The patient is also given dietary and lifestyle advice to prevent constipation and straining, as these can worsen haemorrhoids or cause them to recur.

Case 2: Patient seeking medication advice

A 65-year-old man makes a request at the pharmacy to switch his prescription for cinchocaine hydrochloride 0.5% ww with hydrocortisone 0.5% ww suppositories to ointment.

Consultation

To avoid the consultation being overheard, the pharmacist takes the patient into the consultation room. The patient explains that his GP has examined him and suggested suppositories would be more effective for him owing to their position. He reveals he is reluctant to leave the pharmacy with the suppositories as he does not know how to use them. The pharmacist explains that both formulations contain the same ingredients, which relieve pain, itching and reduce inflammation, and explains how to use the prescribed medication.

Advice

When the pharmacist checks the patient’s understanding using the teach-back method, the patient confides that he does not think that he will be able to do this at work[24]. The pharmacist reassures the patient and provides advice on application standing up. As the pharmacist is a community pharmacist independent prescriber, the patient is encouraged to return if he has difficulties, when they could discuss the supply of a prescription-only ointment for use at work. The patient is given patient information leaflets to help prevent a further recurrence[7,18].

Case 3: Haemorrhoid complication

A 45-year-old woman presents to the pharmacy at the weekend asking for haemorrhoid treatment. She is distressed when describing a swelling around her back passage which is “extremely tender and painful”.

Consultation

The pharmacist takes a patient history, which includes a recent knee injury managed with PRICE (protection, rest, ice, compression, elevation) therapy, a two-week sick note for her employer and prescriptions for co-codamol.

The patient has no prior issues with her bowels, but over the past week has been straining when going to the toilet and passing stools less frequently than normal. The painful swelling at her back passage started two days ago and, after looking up the symptoms online, she has been using cold compresses on the area. She is now avoiding going to the toilet.

Diagnosis and advice

Based on the patient consultation, the pharmacist suspects a thrombosed external haemorrhoid.

The pharmacist highlights the risk factors for haemorrhoids and the contributory roles of opioids and immobility in inducing constipation. The pharmacist explains that thrombosed haemorrhoids can be managed conservatively or with surgical intervention, the latter providing quicker resolution of symptoms. Owing to the patient’s acute presentation, the pharmacist advises the patient to go to a hospital emergency department for further assessment.

- 1Sandler RS, Peery AF. Rethinking What We Know About Hemorrhoids. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2019;17:8–15. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.020

- 2NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. Haemorrhoids. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/haemorrhoids (accessed Jan 2022).

- 3Mott T, Latimer K, Edwards C. Hemorrhoids: Diagnosis and Treatment Options. Am Fam Physician 2018;97:172–9.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29431977

- 4How your pharmacy can help. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/nhs-services/prescriptions-and-pharmacies/pharmacies/how-your-pharmacy-can-help/ (accessed Jan 2022).

- 5Zheng T, Ellinghaus D, Juzenas S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of 944 133 individuals provides insights into the etiology of haemorrhoidal disease. Gut. 2021;70:1538–49. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323868

- 6Haemorrhoids (piles). NHS Inform. 2021.https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/stomach-liver-and-gastrointestinal-tract/haemorrhoids-piles (accessed Jan 2022).

- 7NHS. Piles (haemorrhoids). 2019.https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/piles-haemorrhoids (accessed Jan 2022).

- 8Acheson AG, Scholefield JH. Management of haemorrhoids. BMJ. 2008;336:380–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.39465.674745.80

- 9Lohsiriwat V. Hemorrhoids: From basic pathophysiology to clinical management. WJG. 2012;18:2009. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2009

- 10Migaly J, Sun Z. Review of Hemorrhoid Disease: Presentation and Management. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 2016;29:022–9. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1568144

- 11Ng K, Holzgang M, Young C. Still a Case of ‘No Pain, No Gain’? An Updated and Critical Review of the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management Options for Hemorrhoids in 2020. Ann Coloproctol 2020;36:133–47. doi:10.3393/ac.2020.05.04

- 12Identifying patients with suspected cancer: red flags and referral. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2018. doi:10.1211/pj.2018.20205538

- 13NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary: Anal Fissure. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/anal-fissure/ (accessed Jan 2022).

- 14NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary: Gastointestinal tract (lower) cancers — recognition and referral. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/gastrointestinal-tract-lower-cancers-recognition-referral/ (accessed Jan 2022).

- 15NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. Anaemia – iron deficiency. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/anaemia-iron-deficiency/ (accessed Jan 2022).

- 16Schmidt G, Mandel J. Evaluation and management of suspected sepsis and septic shock in adults. UpToDate. 2021.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-and-management-of-suspected-sepsis-and-septic-shock-in-adults (accessed Jan 2022).

- 17Haemorrhoids. British National Formulary. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/haemorrhoids.html (accessed Jan 2022).

- 18Hydrocortisone for piles and itchy bum. Cream, ointment and suppositories. NHS. 2020.https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/hydrocortisone-for-piles-and-itchy-bottom (accessed Jan 2022).

- 19Haemorrhoids. Treatment algorithm. BMJ Best Practice. 2021.https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/181/pdf/181/Haemorrhoids.pdf (accessed Jan 2022).

- 20Tol RR, Kleijnen J, Watson AJM, et al. European Society of ColoProctology: guideline for haemorrhoidal disease. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:650–62. doi:10.1111/codi.14975

- 21Chen M, Tang T-C, He T-H, et al. Management of haemorrhoids: protocol of an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035287. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035287

- 22Davis BR, Lee-Kong SA, Migaly J, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hemorrhoids. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2018;61:284–92. doi:10.1097/dcr.0000000000001030

- 23Bumps. Best use of medicines in pregnancy. UK teratology information service. https://www.medicinesinpregnancy.org/#:~:text=Bump%20leaflets%20are%20produced%20by%20the%20UK%20Teratology,England%20on%20behalf%20of%20the%20UK%20Health%20Departments (accessed Jan 2022).

- 24The Health Literacy Place. NHS Education for Scotland . https://www.healthliteracyplace.org.uk (accessed Jan 2022).