Shutterstock.com

After reading this case study, you should be able to:

- Identify the symptoms of psoriasis and know its causes;

- Understand why a patient is prescribed a particular treatment, and the expected outcomes and timescales;

- Provide medicines counselling and lifestyle advice relating to psoriasis;

- Screen for psoriatic arthritis and refer patients, if appropriate.

Previously regarded as a skin condition, psoriasis is now best described as a complex, multifactorial inflammatory disease. It is thought to affect 2–4% of Western populations, including the UK, and although the condition is not life-threatening, it is associated with a significant impairment to quality of life, impacting work, family and sexual relations, as well as physical and emotional wellbeing[1–3]. Both sexes are affected equally and, in around 75% of patients, psoriasis first presents between the ages of 15 and 25 years[4]. However, there is a second peak in incidence between the ages of 55 and 60 years[4]. While there are several different types of psoriasis, which have been previously described here, the most common, affecting around 90% of cases, is chronic plaque psoriasis[2,3].

The clinical presentation of plaque psoriasis is well-defined erythematous, silvery/white hyperkeratotic, or thickened, scaling plaques that occur on extensor surfaces of the body (e.g. the elbows and knees), although scalp involvement is present in up to 79% of patients with truncal disease[5]. Abnormal nail plate growth leads to distinctive nail pitting (i.e. small depressions in the nail), accumulation of keratinous material underneath the nail (subungual hyperkeratosis) and onycholysis (i.e. separation of the nail from the nail bed)[6].

The precise cause of psoriasis remains unclear, but it is likely that a combination of genetic, environmental and immunological factors are responsible. The condition is present in up to 30% of first-degree relatives of affected individuals[7]. The immunological component of the condition was realised in the late 1980s, when patients with psoriatic arthritis were treated with the biological agent etanercept — a tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitor[8]. The drug had shown initial efficacy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and, as psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis are disease states in which TNF-alpha is present at an increased concentration in joints and the skin, the conditions were thought to be appropriate therapeutic targets. The investigators observed substantial improvements in a small number of patients with psoriasis who were treated with the agent. Subsequent work has identified that psoriasis is associated with aberrations in several interleukins (IL), such as IL23 and 17A[9].

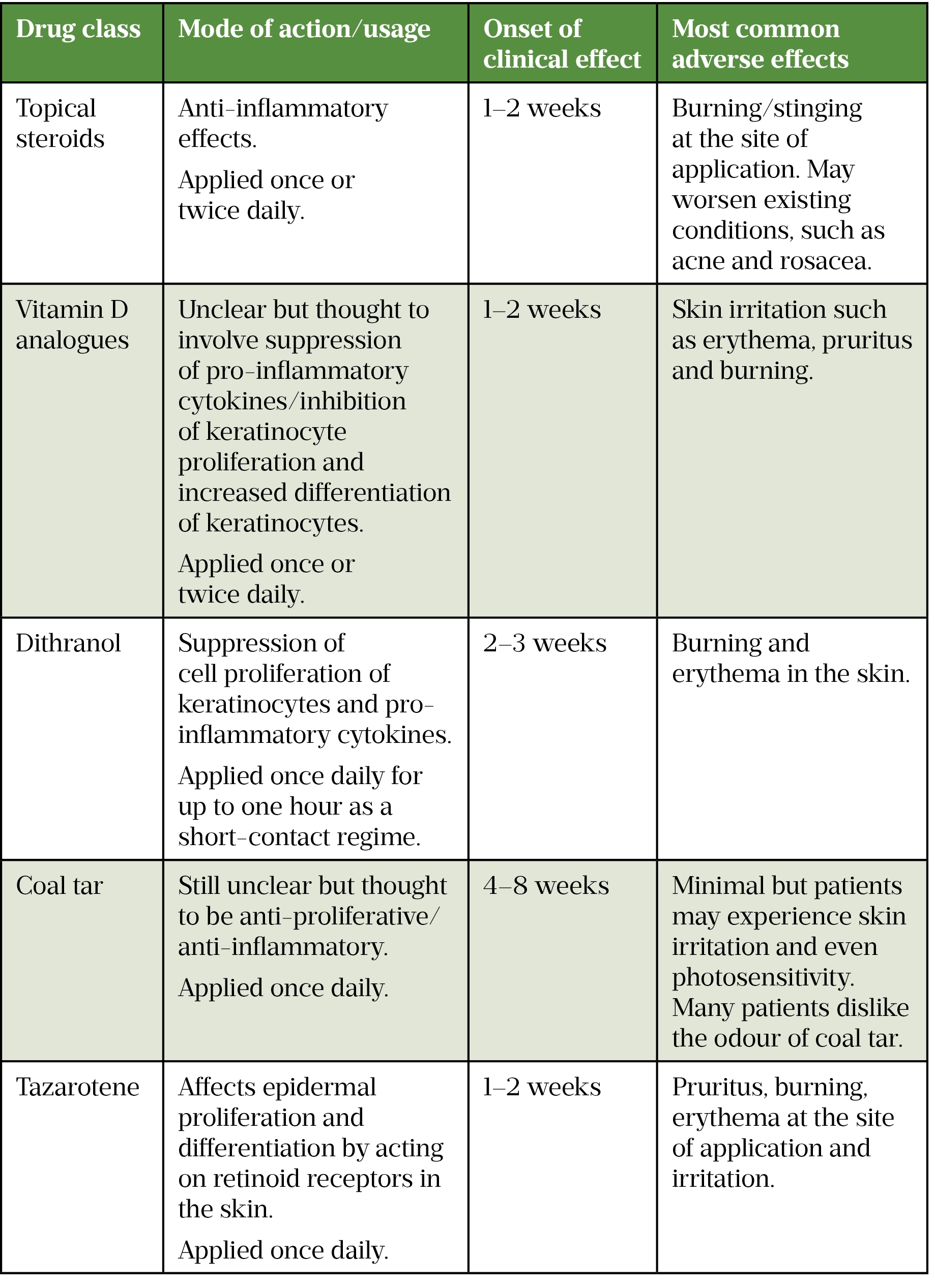

Fortunately, most patients with plaque psoriasis — around 80% — have mild-to-moderate disease that is amenable to treatment in primary care with topical therapies (see Table)[10]. However, research suggests that patients with psoriasis perceive that their care is often suboptimal. For instance, an exploratory focus group of patients with mild-to-moderate psoriasis revealed the erratic and inconsistent use of topical therapies by patients, as well as a clear need for instruction on the correct use of treatments that was often absent from consultations[11]. A second qualitative study demonstrated that patients perceived that healthcare professionals lacked knowledge and expertise in the management of their condition, lacked empathy regarding the impact of the disease and failed to manage psoriasis as a long-term condition[12]. These studies highlight the need for community-based educational information and support to help patients self-manage their condition more effectively. It is important therefore that pharmacy teams handle requests for advice from those with a skin condition, such as psoriasis, with a high degree of sensitivity and do not minimise the psychological impact on an individual[13].

Case presentation

A woman aged 55 years presents to her local pharmacy to collect a new prescription for calcipotriol in combination with betamethasone ointment after being diagnosed with plaque psoriasis on her elbows and scalp. She has not had any skin problems in the past and is concerned that she has developed the problem at such a late stage in her life. The woman has no other health conditions and does not use any other products, but mentions that she recently took paracetamol for about a week for some swelling in two of her fingers, which has now resolved.

Management advice

The patient should be advised that psoriasis is a chronic, relapsing-remitting but incurable condition and that, while it is possible to achieve satisfactory disease control by effective use of treatments, it will likely flare up in the future.

Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that patients are offered a potent corticosteroid applied once daily and the additional use of vitamin D or a vitamin D analogue applied once daily (these products should be applied separately, one in the morning and the other in the evening) for up to four weeks as initial treatment[14]. The use of a combination product such as calcipotriol with betamethasone ointment is advised by NICE but restricted to instances where a patient is unable to use a twice-daily regime or where a once-daily regime would improve adherence.

In contrast, the Primary Care Dermatology Society and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network both endorse the use of a combination product for initial treatment[15,16].

If a combination product is effective, NICE recommends that a topical steroid should not be used at the same site for longer than eight weeks and treatment should continue with the vitamin D analogue alone, allowing for a four-week “steroid-free” interval[14]. Clinical trials have demonstrated that patients are likely to see a 65–74% improvement in disease severity after 4 weeks of treatment and 6–20% of patients experience lesion clearance[17]. The patient should be advised to stop using her active treatment once the raised plaques become flat but to continue with an emollient; if the disease starts to flare up, active treatment can be restarted. There is no need for continued use of combination treatments.

A summary of the other available topical agents for psoriasis treatment is shown in the table.

Lifestyle factors

There is some limited evidence to suggest that lifestyle factors may have an impact on disease severity. A recent Cochrane systematic review showed that calorie restriction could lead to a 75% reduction in disease severity. Furthermore, combining exercise with dietary restriction led to a 28% reduction in disease severity, but there was some uncertainty over the value of this combination, given the wide confidence interval (CI) around the estimate (CI 0.83 to 1.98)[22]. Oral vitamin D supplementation for psoriasis has been studied, owing to the effectiveness of the topical application of vitamin D analogues, but there is a lack of high quality data on its value[23].

Some evidence suggests that smoking, a higher body mass index and stressful life events are independently correlated with psoriasis and that these factors have an additive effect, making the disease worse[24].

The patient can be offered healthy lifestyle advice relating to maintaining a healthy weight and increasing their physical activity[14,25,26].

Emollient use

The patient has not been prescribed an emollient for her psoriasis and it can be suggested that the use of one would be beneficial. Despite a lack of robust evidence, the use of emollients in psoriasis is recommended in the British National Formulary, where it suggests that such treatments help to moisturise dry skin, reduce scaling and relieve itching[18]. By forming an occlusive film over the surface of the skin, an emollient will aid rehydration of the stratum corneum (outermost layer of the skin). This leads to an improvement in the appearance of psoriasis, reducing scale and softening cracked areas of skin[27]. Emollients can be used as soap substitutes and for cleansing in patients with psoriasis; when used topically, the general advice is that the product should ideally be applied 30 minutes before any other psoriasis treatments[28]. Patient acceptability is of utmost importance in the selection of an emollient and the sensation on the skin, odour and level of greasiness will all affect whether a patient is likely to use a particular formulation. In practice, it helps to allow patients to try a range of product samples to ensure they are happy to use it on a regular basis. Given that some patients may continue to smoke, it is important that pharmacists highlight the potential fire risks associated with paraffin-based emollients.

Symptoms indicating complications

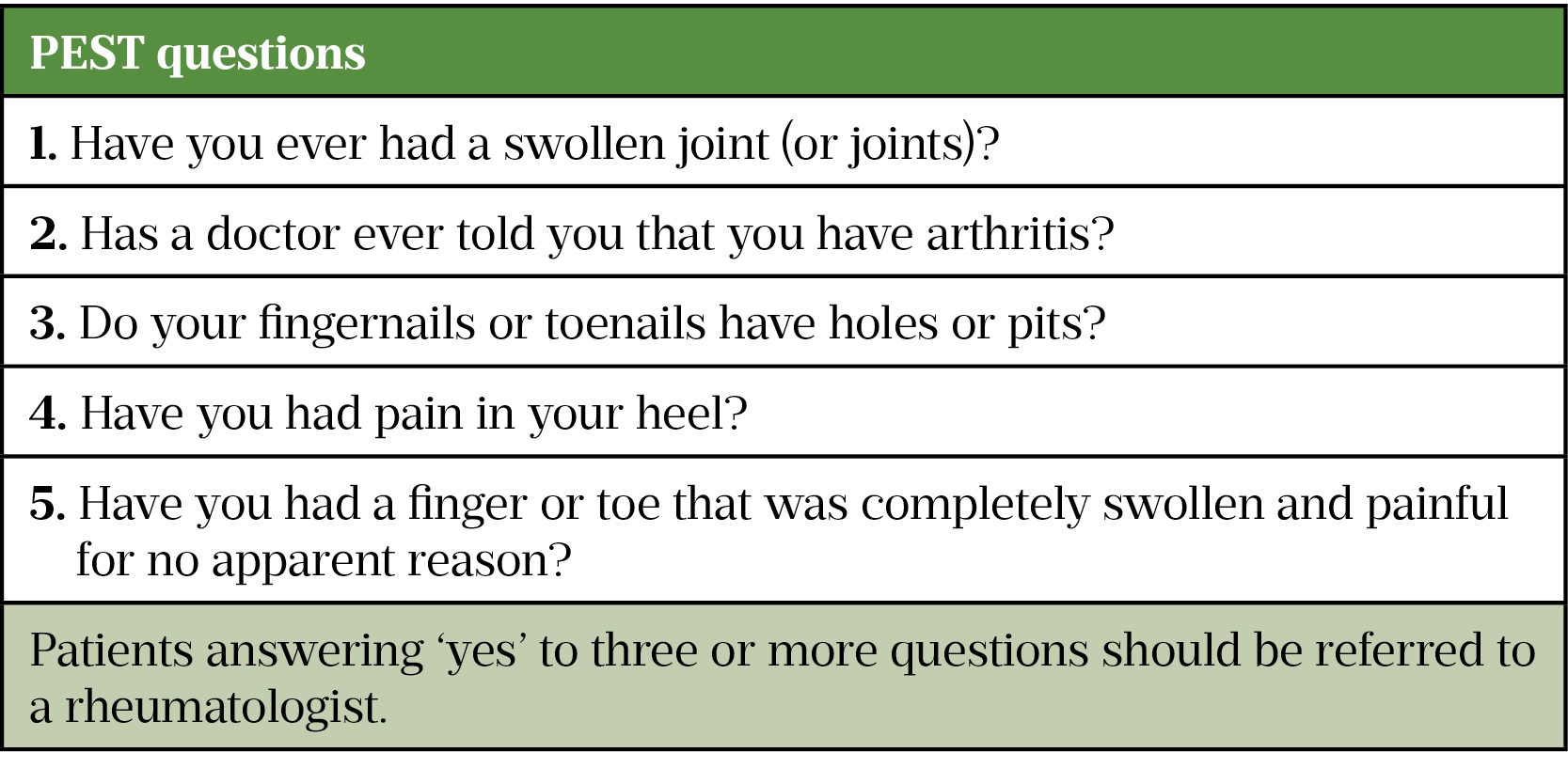

A common and debilitating complication of psoriasis is psoriatic arthritis, a progressive, inflammatory joint disease that eventually leads to disability. According to NICE, psoriatic arthritis affects up to 30% of individuals with psoriasis[14]. Patients can present with dactylitis (i.e. sausage finger/toes) or enthesitis (i.e. inflammation of the entheses that connect tendons and ligaments to the bone), which are the most likely explanation for swollen fingers. Other differential diagnoses for dactylitis include other spondyloarthropathies, sickle cell disease, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis and pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis.

It is important to ask any patient with psoriasis about joint pain as the cause may be psoriatic arthritis. Screening can be undertaken using the psoriasis epidemiological screening tool (PEST; see figure). Any patient answering ‘yes’ to three or more questions should be referred to their GP and onward to a rheumatologist for further assessment.

Summary

Psoriasis is a chronic, long-term condition that deserves the same attention as other chronic conditions, such as asthma or diabetes. Studies have indicated that patients feel healthcare professionals do not provide appropriate advice, and there is some evidence that educational input from community pharmacists leads to improvements in knowledge about psoriasis, disease severity and quality of life[30,31]. The majority of patients in the latter study reported that their psoriasis had improved as a result of the advice provided by community pharmacists[31].

When consulting with a patient with psoriasis, it is important that pharmacists are empathetic to their needs. In the current case, the patient has developed psoriasis at a later stage in their life and is therefore concerned as to whether this will be an acute or chronic condition. Advice on appropriate use of prescribed topical treatments, in combination with modification of lifestyle measures and knowledge of relevant comorbidities, will ensure that the patient is able to self-manage as effectively as possible and minimise the impact of psoriasis on their overall wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

The Pharmaceutical Journal would like to thank and acknowledge Rod Tucker as a clinical adviser, whose expertise and insight contributed to the development of this article.

- 1Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, et al. Global Epidemiology of Psoriasis: A Systematic Review of Incidence and Prevalence. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2013;133:377–85. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

- 2Tucker R. Assessment and management of psoriasis in adults in primary care. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2018.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/assessment-and-management-of-psoriasis-in-adults-in-primary-care (accessed Feb 2022).

- 3Weigle N, McBane S. Psoriasis. Am Fam Physician 2013;87:626–33.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23668525

- 4Griffiths CEM, Christophers E, Barker JNWN, et al. A classification of psoriasis vulgaris according to phenotype. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:258–62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07675.x

- 5van de Kerkhof PCM, de Hoop D, de Korte J, et al. Scalp Psoriasis, Clinical Presentations and Therapeutic Management. Dermatology. 1998;197:326–34. doi:10.1159/000018026

- 6Ngan V, Oakley A. Nail psoriasis. DermNet NZ. 2021.https://dermnetnz.org/topics/nail-psoriasis (accessed Feb 2022).

- 7Gupta R, Debbaneh MG, Liao W. Genetic Epidemiology of Psoriasis. Curr Derm Rep. 2014;3:61–78. doi:10.1007/s13671-013-0066-6

- 8Mease PJ, Goffe BS, Metz J, et al. Etanercept in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a randomised trial. The Lancet. 2000;356:385–90. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02530-7

- 9Jinna S, Strober B. Anti-interleukin-17 treatment of psoriasis. Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 2016;27:311–5. doi:10.3109/09546634.2015.1115816

- 10Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2009;60:643–59. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.032

- 11Ersser SJ, Cowdell FC, Latter SM, et al. Self-management experiences in adults with mild-moderate psoriasis: an exploratory study and implications for improved support. British Journal of Dermatology. 2010;163:1044–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09916.x

- 12Nelson PA, Barker Z, Griffiths CE, et al. ‘On the surface’: a qualitative study of GPs’ and patients’ perspectives on psoriasis. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-14-158

- 13Allinson M, Chaar B. How to demonstrate empathy and compassion in a pharmacy setting. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2019.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/how-to-demonstrate-empathy-and-compassion-in-a-pharmacy-setting (accessed Feb 2022).

- 14Psoriasis: assessment and management (NICE guideline 153). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2012.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153 (accessed Feb 2022).

- 15Psoriasis: an overview and chronic plaque psoriasis — management. Primary Care Dermatology Society. 2022.http://www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/psoriasis-an-overview#management (accessed Feb 2022).

- 16Diagnosis and management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in adults. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2010.https://www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/diagnosis-and-management-of-psoriasis-and-psoriatic-arthritis-in-adults/ (accessed Feb 2022).

- 17Vakirlis E. Calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. TCRM. 2008;Volume 4:141–8. doi:10.2147/tcrm.s1478

- 18Psoriasis. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/psoriasis.html (accessed Feb 2022).

- 19Dithranol. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/dithranol.html (accessed Feb 2022).

- 20Coal tar. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/coal-tar.html (accessed Feb 2022).

- 21Tazarotene. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/tazarotene.html (accessed Feb 2022).

- 22Ko S-H, Chi C-C, Yeh M-L, et al. Lifestyle changes for treating psoriasis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011972.pub2

- 23Stanescu AMA, Simionescu AA, Diaconu CC. Oral Vitamin D Therapy in Patients with Psoriasis. Nutrients. 2021;13:163. doi:10.3390/nu13010163

- 24Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, et al. Cigarette Smoking, Body Mass Index, and Stressful Life Events as Risk Factors for Psoriasis: Results from an Italian Case–Control Study. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2005;125:61–7. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202x.2005.23681.x

- 25Physical activity: brief advice for adults in primary care. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2013.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph44

- 26Preventing excess weight gain. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng7

- 27Onselen JV. An overview of psoriasis and the role of emollient therapy. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2013;18:174–9. doi:10.12968/bjcn.2013.18.4.174

- 28Topical treatments for psoriasis. British Association of Dermatologists. 2021.https://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=123&itemtype=document (accessed Feb 2022).

- 29Ibrahim G, Buch M, Lawson C, et al. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009;27:469–74.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19604440

- 30Tucker R, Stewart D. The role of community pharmacists in supporting self-management in patients with psoriasis. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2016;25:140–6. doi:10.1111/ijpp.12298

- 31Tucker R, Stewart D. Patient and pharmacist perceptions of a pharmacist-led educational intervention for people with psoriasis. Self Care. 2016.https://selfcarejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Tucker-7.4-.18-31.pdf (accessed Feb 2022).