Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should:

- Know the challenges when considering anticoagulation in women and how these considerations can change over a woman’s life course;

- Understand best practice for anticoagulation in the presence of heavy menstrual bleeding;

- Know how contraception should be managed in women receiving anticoagulation;

- Understand the considerations for anticoagulation in pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Introduction

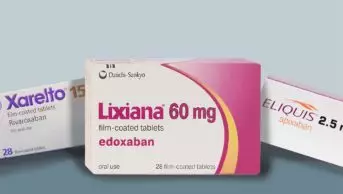

Anticoagulants are commonly prescribed, high-risk medications. The direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are frequently used to treat venous thromboembolism (VTE) and for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation1. While DOACs have an improved safety profile compared with vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin, patients with mechanical heart valves, severe renal dysfunction, certain forms of antiphospholipid syndrome, and on interacting medications will still require anticoagulation with these agents1,2.

The term VTE encompasses both deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Globally, it affects more than 1 in 12 individuals during their lifetime and in the UK it is the third most common cardiovascular condition3,4. Men and women have an overall similar lifetime risk of developing a first episode of VTE5. Women of childbearing age are at increased risk of VTE, secondary to the transient risk factors of combined hormonal contraception (CHC) and pregnancy6.

The term abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) encompasses heavy menstrual bleeding and all other types of abnormal uterine bleeding, such as post-menopausal bleeding and intermenstrual bleeding. AUB affects one-third of reproductive aged women and it has been known for some time that the use of anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists (VKA) causes excess bleeding in women7. In a retrospective study of 900 patients on warfarin in the United States, the risk of bleeding was reported to be 1.9 times greater (95% confidence interval [CI]; 1.3–3.0) in women, with excess bleeding being almost exclusively vaginal or uterine8.

This issue is not unique to the traditional anticoagulants. In the landmark clinical trials for the DOACs, the rate of AUB was not initially reported9–12. Post-hoc analysis was only reported once case series of excess AUB with DOACs began to emerge owing to their widespread use. Post-hoc analysis revealed a 0.3% risk of major uterine bleeding in the low molecular weight heparin (LMWH)/VKA group, compared with a 2.1% risk in the DOAC rivaroxaban group10.

For both apixaban and edoxaban, reported clinically relevant non-major bleeding was more likely to be of vaginal origin when compared with LMWH/warfarin13,14. In the United States, Samuelson Bannow et al. performed a retrospective cohort study of 195 women with a new prescription for oral anticoagulation (OAC)15. One-third of patients required treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding within six months of starting OAC therapy and 45% of women on rivaroxaban required treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding within six months, compared with 23% of women on apixaban. They also highlighted a lack of documented menstrual history for most women newly initiated on OAC15.

Perception of a ‘normal’ menstrual cycle will vary between women. Samuelson Bannow et al. describe a normal menstrual cycle as 21–35 days in length with a bleed duration of 5–7 days and blood loss of about 53mL per cycle7.

Samuelson Bannow et al. define heavy menstrual bleeding as a period lasting >7 days, >80mL blood loss per cycle, passing clots bigger than a 50-pence piece, changing sanitary protection more than hourly, and overnight or bleeding through clothing. It is also important to include the often under-reported effect on quality of life in the definition of heavy menstrual bleeding. Therefore, any bleeding that interferes with physical, social, emotional or material quality of life should be considered as heavy menstrual bleeding7,16.

Unfortunately, heavy menstrual bleeding often goes unreported by women who may ‘put up with’ it and accept it as a normal or expected consequence of anticoagulation.

This article will use clinical cases to address challenges that commonly present for women prescribed anticoagulation: heavy menstrual bleeding, the use of hormonal contraception, anticoagulation during pregnancy and the use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) during menopause.

Case study 1

RP, a 30-year-old woman, presents to the emergency department with a painful, swollen leg. She has no notable past medical history. She takes microgynon for contraception and heavy periods.

She is diagnosed with popliteal DVT (i.e. a blood clot in the vein behind her knee) in the emergency department and started on rivaroxaban 15mg twice daily for 21 days then 20mg daily.

Microgynon is stopped owing to VTE risk, which is increased fourfold using combined hormonal contraceptives (CHC)17; however, the absolute risk of VTE remains low.

RP presents three weeks later to the pharmacist-led anticoagulation clinic with heavy menstrual bleeding — changing tampons every hour, unable to leave the house.

A thorough menstruation history should have been taken before starting anticoagulation. At the clinic, a questionnaire is used to take RP’s menstrual history; this questionnaire covers intervals between cycles, period length and how heavy a woman’s period is. This questionnaire is used to identify patients at highest risk of anticoagulation-associated heavy menstrual bleeding and results in more frequent monitoring of patients as appropriate. Full blood count and ferritin should be checked at baseline and as appropriate thereafter dependent on bleeding.

As a result of clinical experience and evidence from the literature, apixaban is commonly used first-line for the treatment of VTE in menstruating women. RP should be switched to apixaban 5mg twice daily13. Had RP’s heavy menstrual bleeding been picked up in the ED, she should have been initiated on apixaban 10mg twice daily for one week and then 5mg twice daily for at least three months.

On monitoring, her haemoglobin is 110 and ferritin is 50. Therefore, iron supplementation is not indicated at present.

RP should be counselled that she should contact the anticoagulation clinic if her periods continue to be heavier than normal, causing flooding or passing clots or restricting her daily activities. She should be counselled to seek urgent medical attention if she feels dizzy, faint or short of breath. A useful resource is an information leaflet, an example of which can be found here or signpost them to this video for more information.

Contraception post VTE diagnosis

A diagnosis of VTE affects a woman’s options for contraception. It is important that women are counselled appropriately.

One common misconception is that CHC should always be stopped as soon as VTE is diagnosed. There is some controversy regarding the use of hormonal contraceptives in women diagnosed with VTE. In practice, for most patients who are anticoagulated, CHC can be continued until one month before stopping anticoagulation. The intensity of anticoagulation should negate the risk of VTE associated with CHC and immediate discontinuation of CHC can lead to unwanted pregnancy and can exacerbate heavy menstrual bleeding18.

The UK medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use provides guidance on the safety of different methods of contraception in patients with pre-existing medical conditions19. It defines current VTE or a history of VTE as a condition that represents an unacceptable health risk if the CHC method of contraception is used (without anticoagulation). All other methods of hormonal and intrauterine contraception are defined as generally acceptable in this patient group as the advantages generally outweigh the risks19.

RP could be restarted on CHC while she is being anticoagulated or switched to an alternative (e.g. a progesterone-only form of contraception) depending on her preference to manage heavy menstrual bleeding.

Duration of anticoagulation

Guidance treats hormone-associated VTE as a provoked event and therefore, generally long-term anticoagulation is not indicated, provided hormonal contraception can be stopped20. The risk of recurrence in patients with VTE provoked by a non-surgical trigger (for example the use of CHC) is estimated at 5% within one year and 15% at five years, compared with 30% at five years for an unprovoked VTE21. RP would be advised to stop anticoagulation at three months owing to the low risk of recurrence.

Follow-up

RP should be followed up monthly in the anticoagulation clinic during treatment to assess the severity of her bleeding. If heavy menstrual bleeding persists despite the change of, and reintroduction of, the CHC then other treatment strategies would include the addition of tranexamic acid (after the acute period of VTE) 1g three times daily for 4 days or a referral to gynaecology for surgical strategies, such as endometrial ablation, as appropriate.

Case study 2

RP is now aged 35 years and is 14 weeks pregnant with her first child. She presents to the maternal assessment unit with a swollen leg and is diagnosed with a new distal DVT.

Pregnancy increases the risk of VTE four to five-fold, spanning all three trimesters and peaking during the post-partum period6. The increased risk of VTE during pregnancy results from a combination of altered coagulation factors, venous stasis and vascular damage. In 2024, the MBRRACE-UK ‘Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care’ annual report stated that thrombosis and thromboembolism is the leading cause of maternal death in the UK with an overall mortality rate of 2.87 per 100,000 maternities22.

The treatment of VTE in pregnancy presents several challenges, mainly related to limited available treatment options, and the management of the bleeding risk associated with epidural and delivery and during the post-partum period.

The treatment of choice for VTE in pregnancy is low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). Evidence for the use of LMWH comes from a systematic review of 64 reports of 2,777 pregnancies demonstrating a low risk of VTE recurrence23. Warfarin crosses the placenta and is associated with early risks of warfarin embryopathy and late risk of foetal intracranial haemorrhage24. The DOACs are not recommended in pregnancy. Clinical evidence for the risk of using DOACs in pregnancy is scarce and all manufacturers advise against their use25–28.

The route of administration of LMWH by subcutaneous injection may present limitations in terms of adherence to treatment. Patients are taught to self-inject, and are provided with written instructions by pharmacists or nurses within the thrombosis or obstetric team. The initial dose of LMWH heparin should be calculated based on the woman’s booking or early pregnancy weight29. RP’s booking weight was 65kg. She would be prescribed enoxaparin 100mg daily (based on 1.5mg/kg). Other LMWHs can also be used in pregnancy.

In pregnancy, there is an increase in maternal plasma volume of around 50% and an increase in volume of distribution, together with a 50% increase in glomerular filtration rate30. This could result in shorter half-lives and lower peak concentrations for LMWH in pregnant patients; this informed previous guidelines produced by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), which recommended high dose and twice-daily frequency for LMWH. However, there are limited clinical data to support this approach and the current RCOG guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence to recommend whether the dose of LMWH should be once or twice daily29,31. In current clinical practice, enoxaparin 1mg/kg twice daily for 4 weeks is used for patients with a pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis with a large clot burden, reducing to 1.5mg/kg once daily subsequently and 1.5mg/kg daily from the outset for most low-moderate-risk patients.

Anti-factor Xa levels can be used to monitor the safety and efficacy of LMWH in some high-risk patients (e.g. extremes of body weight, severe renal impairment). Routine measurement of anti-Xa activity is not recommended except in women at extremes of body weight, in renal impairment or in patients with recurrent VTE. Patients are generally treated throughout the pregnancy and then for at least six weeks afterwards to cover the prothrombotic post-partum period. The total minimum duration of anticoagulation is three to six months, as for VTE in non-pregnant patients29,31.

RP is treated with LMWH (e.g. enoxaparin 1.5mg/kg daily) for her entire pregnancy and for 6 weeks post-partum. As she is breastfeeding, she will stay on LMWH post-partum; if not, she could switch to a DOAC when the post-partum bleeding risk allows. It would be unlikely to be worth starting warfarin for such a short period of time. RP has had two episodes of DVT, but both were provoked (by the CHC and pregnancy) so she would not require long-term anticoagulation.

Anticoagulation around delivery should be managed by a specialist team. Once patients are in established labour, LMWH should be withheld. Regional anaesthesia should not be undertaken until at least 24 hours have elapsed since the last therapeutic dose of LMWH32.

Breastfeeding

RP should be advised that LMWH, unfractionated heparin and warfarin are minimally secreted into breast milk and are considered safe for women who are breastfeeding29. An effective and safe oral alternative to warfarin would have significant advantages in this patient group. All DOACs are contraindicated for breastfeeding women owing to lack of clinical data. In a small 2021 study, rivaroxaban transferred into breast milk in very small quantities whereas apixaban transferred in significant concentrations33.

The ‘Dabigatran Presence in Breast Milk (DALMATION)’ study included only two women but showed that dabigatran is secreted into breast milk albeit in very small quantities34. A recent case report by Yamashita et al., describes treating two breastfeeding women with rivaroxaban for VTE35. The rivaroxaban concentration was below the lower limit of quantification even after high exposure based on five days of breastfeeding. Further study with larger patient numbers is needed in this area.

Follow-up

RP would be monitored throughout her pregnancy by the obstetric and thrombosis teams.

RP should be offered pre-pregnancy counselling by an obstetric or thrombosis specialist team for future pregnancies, and she would be offered thromboprophylaxis with LMWH throughout the antenatal period29.

Case study 3

RP is now aged 51 years and is perimenopausal. She has been experiencing hot flushes and some anxiety, and visits her GP to ask about HRT.

A 2013 study by Roach et al. showed that the risk of VTE increases two- to four-fold in post-menopausal women using HRT36. Results from another study suggest that patients using transdermal HRT preparations have a lower risk of VTE when compared with oral preparations6. A meta-analysis in 2008, which included eight observational and nine randomised controlled trials, revealed that oral oestrogen was associated with a significantly increased risk of VTE compared to those not on HRT, with a lesser risk for users of transdermal HRT37.

Meanwhile, results from the Million Women Study confirmed that the highest risk of VTE was associated with combined preparations (oestrogen and progesterone) and found no increased risk with transdermal oestrogen38.

Bagot et al. found that thrombin generation is significantly increased in women who use HRT via the oral route. This is probably mediated by the hepatic first-pass metabolism of estrone, the main metabolite of oral oestradiol. Transdermal HRT avoids first-pass liver metabolism and, as such, the effect on coagulation is reduced39.

RP could start transdermal HRT with a combined HRT patch or with oestradiol gel and micronised progesterone on days 14–28 of her menstrual cycle.

Her GP would then follow her up in three months to monitor symptoms and side effects.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by this case, there are myriad challenges associated with the use of anticoagulation in women. Pregnancy and hormonal therapies increase the risk of VTE, and the use of anticoagulation to treat VTE increases the risk of abnormal uterine bleeding. The use of anticoagulation in women requires careful consideration of the risks and benefits, an individualised approach to treatment, and monitoring and recognition of the importance of allowing women to make an informed choice about their management.

There is also a pressing need for more research to guide management decisions and to broaden treatment options for women who require anticoagulation.

- 1.Oral anticoagulants. British National Formulary. Accessed January 2026. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/oral-anticoagulants/

- 2.Correction to: Direct Oral Anticoagulants Versus Warfarin in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Patient-Level Network Meta-Analyses of Randomized Clinical Trials With Interaction Testing by Age and Sex. Circulation. 2022;145(8). doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000001058

- 3.Brækkan SK, Hansen JB. VTE epidemiology and challenges for VTE prevention at the population level. Thrombosis Update. 2023;10:100132. doi:10.1016/j.tru.2023.100132

- 4.Pulmonary embolism. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. Accessed January 2026. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/pulmonary-embolism/background-information/prevalence/

- 5.Douketis J, Tosetto A, Marcucci M, et al. Risk of recurrence after venous thromboembolism in men and women: patient level meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342(feb24 2):d813-d813. doi:10.1136/bmj.d813

- 6.Speed V, Roberts LN, Patel JP, Arya R. Venous thromboembolism and women’s health. Br J Haematol. 2018;183(3):346-363. doi:10.1111/bjh.15608

- 7.Samuelson Bannow B, McLintock C, James P. Menstruation, anticoagulation, and contraception: VTE and uterine bleeding. Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2021;5(5):e12570. doi:10.1002/rth2.12570

- 8.Fihn SD, McDonell M, Martin D, et al. Risk Factors for Complications of Chronic Anticoagulation: A Multicenter Study. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):511-520. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00005

- 9.Edoxaban versus Warfarin for the Treatment of Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(15):1406-1415. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1306638

- 10.Oral Rivaroxaban for Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2499-2510. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1007903

- 11.Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral Apixaban for the Treatment of Acute Venous Thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):799-808. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1302507

- 12.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139-1151. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0905561

- 13.Scheres L, Brekelmans M, Ageno W, et al. Abnormal vaginal bleeding in women of reproductive age treated with edoxaban or warfarin for venous thromboembolism: a post hoc analysis of the Hokusai‐<scp>VTE</scp> study. BJOG. 2018;125(12):1581-1589. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15388

- 14.Bleker S, Hutten B, Timmermans A, et al. Abnormal vaginal bleeding in women with venous thromboembolism treated with apixaban or warfarin. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(04):809-815. doi:10.1160/th16-11-0874

- 15.Samuelson Bannow BT, Chi V, Sochacki P, McCarty OJT, Baldwin MK, Edelman AB. Heavy menstrual bleeding in women on oral anticoagulants. Thrombosis Research. 2021;197:114-119. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.11.014

- 16.Menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2024. Accessed January 2026. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/menorrhagia-heavy-menstrual-bleeding/background-information/definition/

- 17.de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;2014(3). doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010813.pub2

- 18.Scheres LJJ, Middeldorp S. Hormone-related thrombosis: duration of anticoagulation, risk of recurrence, and the role of hypercoagulability testing. Hematology. 2024;2024(1):664-671. doi:10.1182/hematology.2024000593

- 19.UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (UKMEC). The College of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. 2019. Accessed January 2026. https://www.cosrh.org/Public/Public/Standards-and-Guidance/uk-medical-eligibility-criteria-for-contraceptive-use-ukmec.aspx

- 20.BAGLIN T, BAUER K, DOUKETIS J, BULLER H, SRIVASTAVA A, JOHNSON G. Duration of anticoagulant therapy after a first episode of an unprovoked pulmonary embolus or deep vein thrombosis: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2012;10(4):698-702. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04662.x

- 21.Kearon C, Akl EA. Duration of anticoagulant therapy for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood. 2014;123(12):1794-1801. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-12-512681

- 22.Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care 2024 – Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2020-22. Oxford Population Health (NPEU). 2024. Accessed January 2026. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-reports/maternal-report-2020-2022

- 23.Greer IA, Nelson-Piercy C. Low-molecular-weight heparins for thromboprophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy: a systematic review of safety and efficacy. Blood. 2005;106(2):401-407. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-02-0626

- 24.Bates SM, Greer IA, Middeldorp S, Veenstra DL, Prabulos AM, Vandvik PO. VTE, Thrombophilia, Antithrombotic Therapy, and Pregnancy. Chest. 2012;141(2):e691S-e736S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2300

- 25.Xarelto 20mg film-coated tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2024. Accessed January 2026. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2793/smpc

- 26.Eliquis 5 mg film-coated tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2024. Accessed January 2026. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2878/smpc

- 27.Pradaxa 150 mg hard capsules. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2025. Accessed January 2026. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4703/smpc#gref

- 28.Lixiana 60mg Film-Coated Tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2025. Accessed January 2026. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6905/smpc#gref

- 29.Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the peurperium. Green-top Guideline No. 37b. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . 2015. Accessed January 2026. https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/browse-all-guidance/green-top-guidelines/thrombosis-and-embolism-during-pregnancy-and-the-puerperium-acute-management-green-top-guideline-no-37b/

- 30.PATEL JP, HUNT BJ. Where do we go now with low molecular weight heparin use in obstetric care? Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2008;6(9):1461-1467. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03048.x

- 31.Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the peurperium. Green-top Guideline No. 37a. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2015. Accessed January 2026. https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/browse-all-guidance/green-top-guidelines/reducing-the-risk-of-thrombosis-and-embolism-during-pregnancy-and-the-puerperium-green-top-guideline-no-37a/

- 32.Arya R. How I manage venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Br J Haematol. 2011;153(6):698-708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08684.x

- 33.Zhao Y. Predicting infant exposure to direct oral anticoagulants in breastfeeding mothers. King’s College London. 2021. Accessed January 2026. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/studentTheses/predicting-infant-exposure-to-direct-oral-anticoagulants-in-breas/

- 34.Ayuk P, Kampouraki E, Truemann A, et al. Investigation of dabigatran secretion into breast milk: Implications for oral thromboprophylaxis in post‐partum women. American J Hematol. 2019;95(1). doi:10.1002/ajh.25652

- 35.Yamashita Y, Hira D, Morita M, et al. Potential treatment option of rivaroxaban for breastfeeding women: A case series. Thrombosis Research. 2024;237:141-144. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2024.04.003

- 36.ROACH REJ, LIJFERING WM, HELMERHORST FM, CANNEGIETER SC, ROSENDAAL FR, van HYLCKAMA VLIEG A. The risk of venous thrombosis in women over 50 years old using oral contraception or postmenopausal hormone therapy. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2013;11(1):124-131. doi:10.1111/jth.12060

- 37.Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GDO, Scarabin PY. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7655):1227-1231. doi:10.1136/bmj.39555.441944.be

- 38.SWEETLAND S, BERAL V, BALKWILL A, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk in relation to use of different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a large prospective study. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2012;10(11):2277-2286. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04919.x

- 39.BAGOT CN, MARSH MS, WHITEHEAD M, et al. The effect of estrone on thrombin generation may explain the different thrombotic risk between oral and transdermal hormone replacement therapy. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2010;8(8):1736-1744. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03953.x