ISM/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand how genomics is being used to diagnose familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH);

- Understand the genetics of FH and the importance of identifying patients at risk;

- Understand the role of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians in identifying patients at risk of FH and referring them for genetic testing and family tracing;

- Know the available options for the ongoing management of FH.

Lifestyle factors, such as weight management and smoking, can lead to raised cholesterol and heart disease in mid to later life, but for more than a quarter of a million people in the UK, diet and ageing are not the only considerations[1–3]. Around 1 in 250 people have an inherited condition called heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH), which results in a raised level of cholesterol from birth and a significantly increased risk of early heart disease[4,5].

Without treatment for FH, the incidence of fatal or non-fatal heart attacks is around 50% in men by the age of 50 years and around 30% in women by the age of 60 years, and there is growing evidence that suggests reducing lifetime exposure to raised low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol is more important than the magnitude of the LDL cholesterol level itself[4,5]. FH is easily diagnosed with a simple genetic test, and the risk of premature cardiovascular disease (CVD) can be reduced through early diagnosis and prompt introduction of treatment[6].

The biggest barrier to improving FH outcomes is that most people are unaware that they have the condition. In 2019, the ‘NHS Long Term Plan’ reported that only 7% of people in England with FH had been identified and a commitment was made to raise the number to at least 25% by 2024 through the NHS genomics programme[7].

Primary care networks, including pharmacists and pharmacy teams, are supporting this commitment by identifying people who have risk factors for FH (see below) and facilitating referral to secondary care services for genetic counselling and diagnostic testing[8]. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians also support lipid optimisation, be this in community pharmacy, primary care, or more complex case management in secondary care lipid clinics.

This article provides an overview of the symptoms, diagnostic criteria and management of FH, and describes how pharmacists and their teams working across sectors can contribute to improving outcomes for these patients.

Genetics and genetic testing

FH usually results from a mutation in one of four genes: the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene, the apolipoprotein B (APOB) gene, the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) gene and the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene[4]. LDLR mutations are the most common and account for 80–95% of FH cases, with more than 200 genetic variants documented in the UK[2,9]. LDL receptors are expressed by cells and bind to circulating LDL in the bloodstream. The LDL is then taken up by the cells and either used, stored for later or broken down by the liver. In people with FH, the process of cellular uptake of circulating LDL is impaired, leading to a build-up of cholesterol in the blood[3].

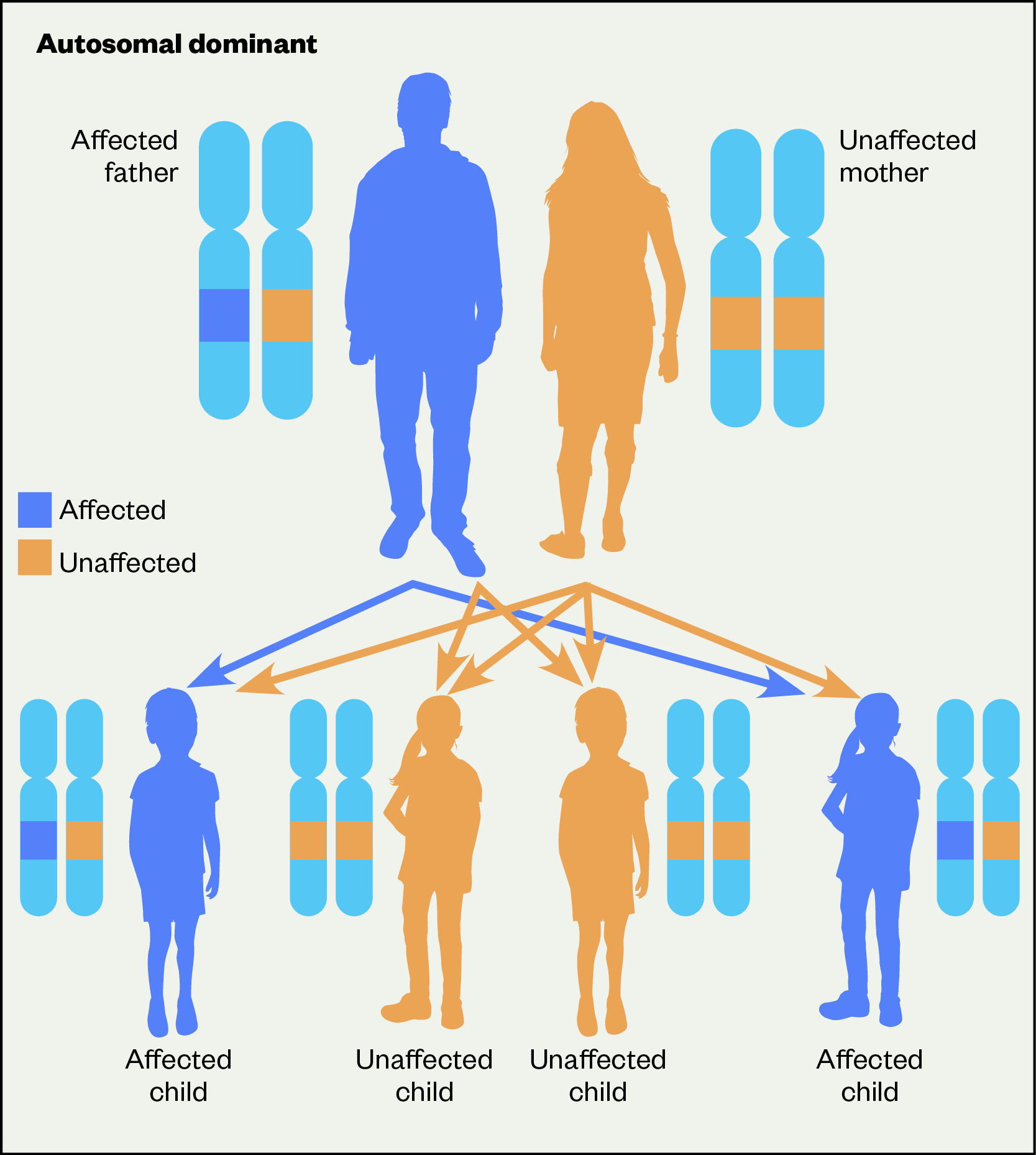

Heterozygous FH is an autosomal dominant inherited condition where one parent with an altered gene has a 50% chance of passing on that altered gene to each of their children[2]. If a child inherits a mutated gene from one parent, they will have heterozygous FH. Sometimes both parents can have the condition and if a child inherits the mutated gene from both parents, they will have homozygous FH. Individuals with homozygous FH have a more severe form of hypercholesterolemia (estimated to affect 1 in 3 million) with heart attack and death often occurring before the age of 30 years and sometimes even in childhood[5].

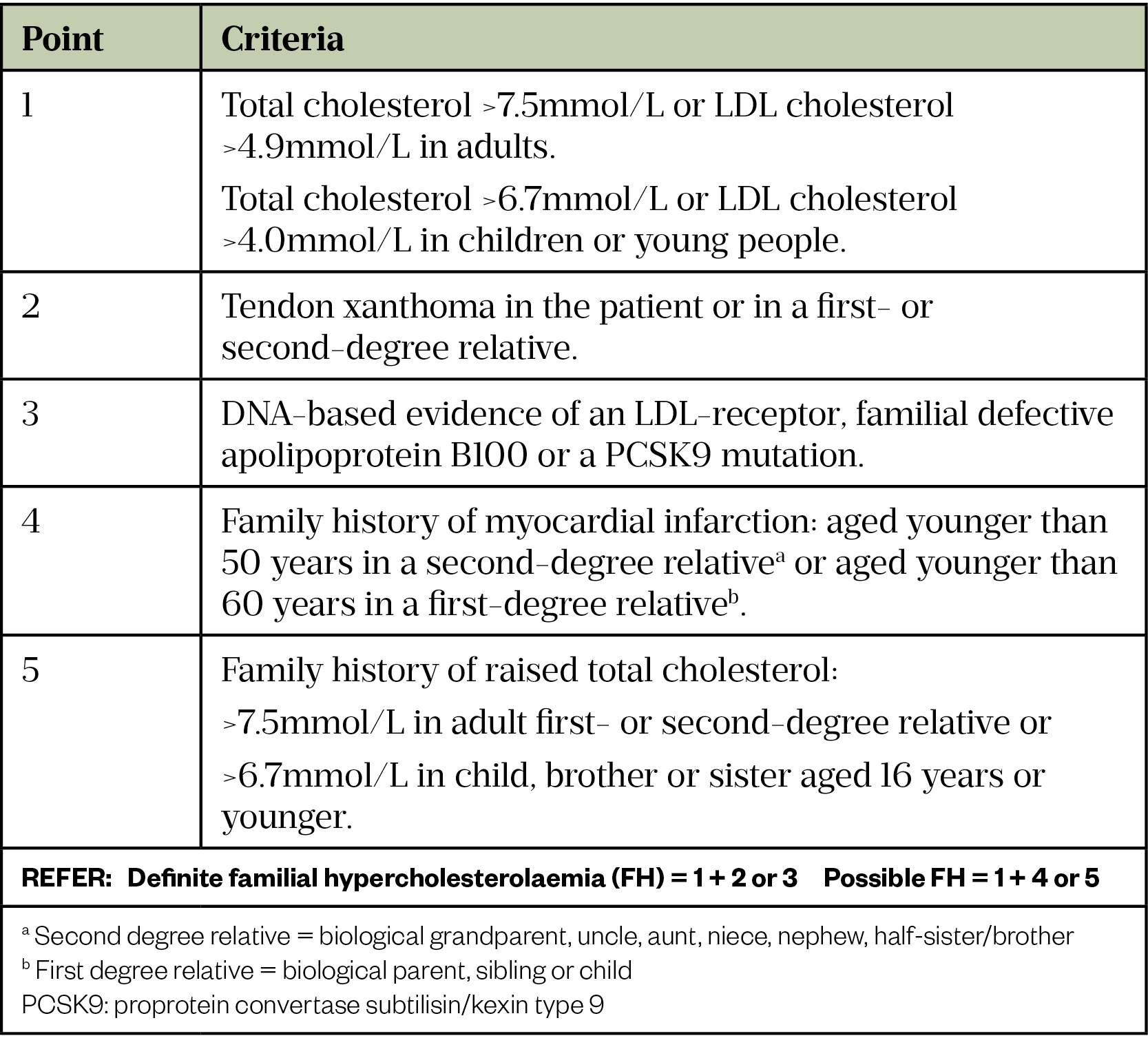

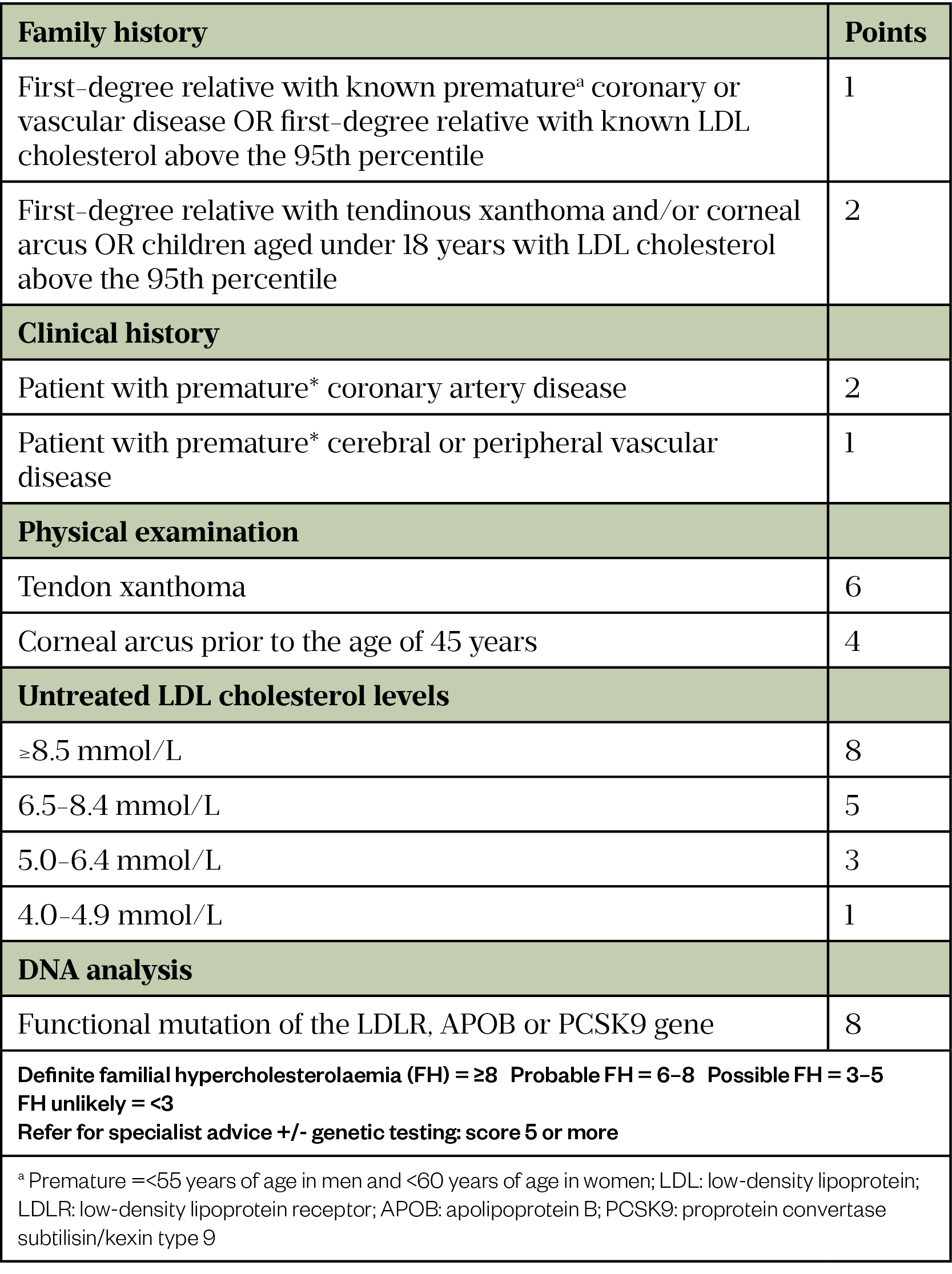

Genetic testing for FH is available on the NHS throughout the UK. In England, it is provided through the NHS Genomic Medicine Service, as outlined in the National Genomic Test Directory[10]. In Wales, the All Wales Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Service has been providing a service for the diagnosis and treatment of FH since 2010[3,11]. Genetic testing in Scotland is available for all patients who meet the Simon Broome or Dutch criteria (see Table 1 and Table 2) and, in Northern Ireland, testing is available to patients who meet a locally modified version of the Dutch or FH Wales criteria[3]. To access this testing, GPs and other healthcare professionals should refer eligible patients with a possible or probable diagnosis of FH to a specialist to confirm the diagnosis and start family cascade testing as appropriate[3].

Early testing and diagnosis mean that treatment can be initiated before complications develop. Cascade testing of relatives of individuals with FH is highly cost effective[12]. Once a patient tests positive for FH, their immediate relatives are invited for testing and treatment. If any of these people test positive, their immediate family are also invited for testing[12]. The current recommendations are that cascade DNA testing should be offered to first, second and, when possible, third-degree biological relatives of people with a genetic diagnosis of FH[13]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence estimates that if 50% of the predicted relatives of people with FH were diagnosed and treated, the NHS could save £1.7m per year on healthcare for heart disease by preventing cardiovascular events[12,13].

Case finding in adults

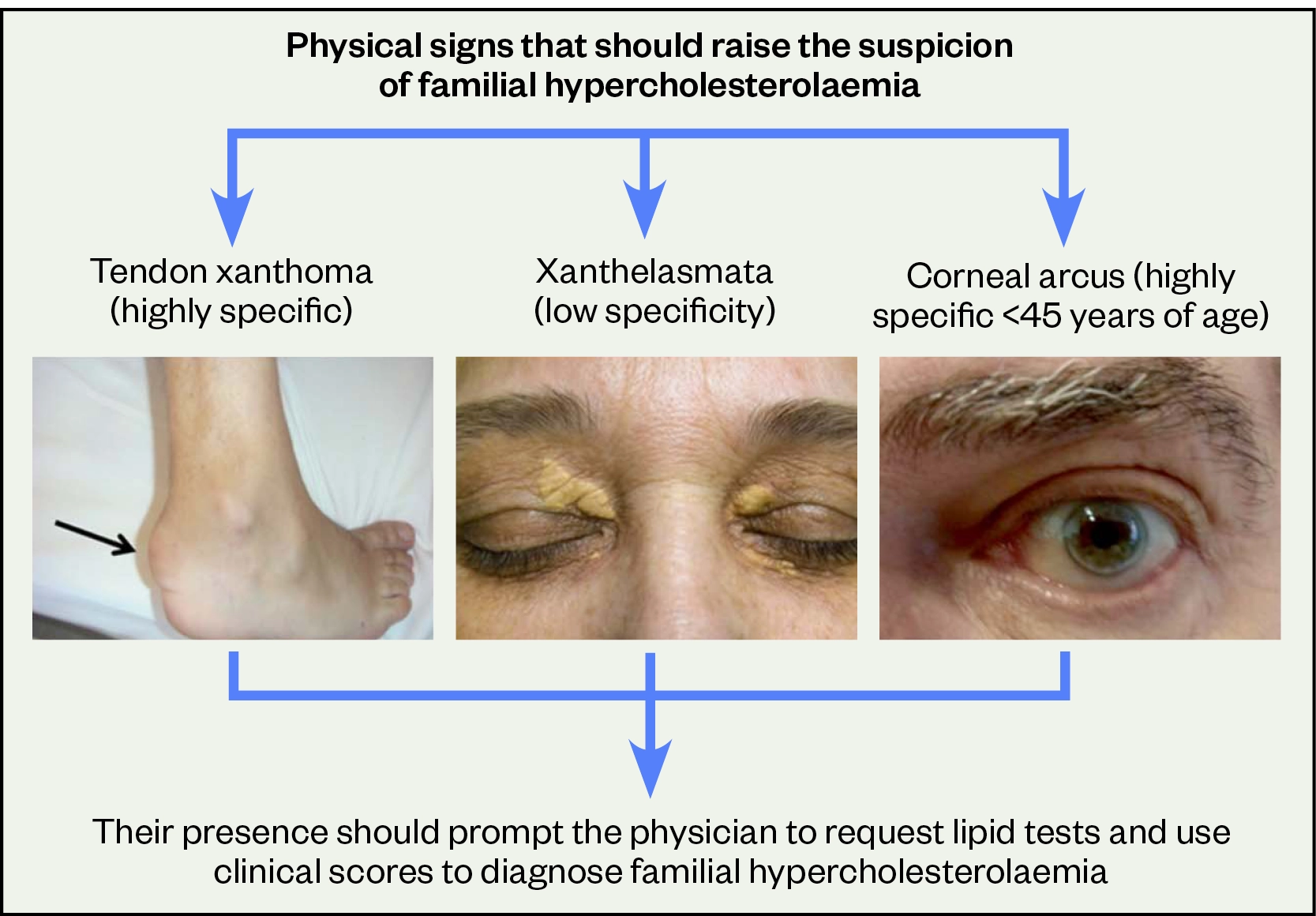

Most people with raised cholesterol will be asymptomatic and the first manifestation of FH may be a presentation with CVD in middle-age, reinforcing the importance of early identification and treatment. A diagnosis of FH should be considered in adults with a total cholesterol level >7.5 mmol/L or a personal and/or family history of premature coronary heart disease or proven FH in a family member[3]. Physical signs, if present, should also raise suspicion of FH (see Figure 2)[14].

Reproduced with permission from Elsevier

Reproduced with permission from

Pharmacy teams in primary care can support case finding by:

- Ensuring people with the code ‘FH’ on their GP record are correctly coded and have had appropriate testing, and that family testing has been offered /undertaken;

- Systematic identification utilising GP system searches. An appropriately qualified healthcare professional (which may be the pharmacist) within the GP practice can then assess the likelihood of FH (i.e. by use of the Simon Broome or Dutch Lipid Clinic Network criteria — see Table 1 and Table 2 below or the FH Wales score) with onward referral to specialist services where indicated. Search examples can be found on the Clinical Digital Resource Collaborative and UCL Proactive care frameworks websites[13,15].

In secondary care settings, the pharmacy team can review the lipid profile and medical history of patients with CVD. These patients may present as acute admissions to cardiology, stroke, diabetes and vascular teams or to outpatient services, and will have a lipid profile undertaken as a routine part of their care. Where a diagnosis of FH is being considered, the clinical team may then refer to specialist services for a more definitive diagnosis.

Regardless of setting, assessment should also take into consideration secondary causes of hyperlipidaemia, which will need to be managed. These may include uncontrolled diabetes, untreated hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, the menopause, chronic kidney disease, obesity, alcohol misuse or medication (e.g. thiazide diuretics, ciclosporin)[13]. The pharmacy team can review medications and provide advice on treatment options where necessary.

The roles described above are dependent on review of lipid profiles that have already been undertaken. Community pharmacies and primary care teams may also offer cholesterol checks via NHS health checks, as part of long-term condition reviews, or for patients where high cholesterol or premature coronary disease has been identified in a family member, to support earlier identification of FH patients.

Management

A heart-healthy lifestyle, including keeping active, diet, weight management, avoiding smoking, good blood pressure control and moderation of alcohol, is recommended[16]. All pharmacy teams, regardless of setting, should take every opportunity to offer advice and support on healthy lifestyle and diet. Dietary advice should include swapping saturated fats to more heart-healthy fats and, if eaten, preferentially choosing lower fat dairy products, fish and white meat, and including fruit, vegetables and wholegrains in the diet. If red meat is eaten, ideally this should be lean and people could also be advised to consider more plant foods by swapping some meat-based meals for vegetarian options. The charity Heart UK is an excellent resource for patients and its website includes recipe suggestions[16].

Lipid-lowering medication

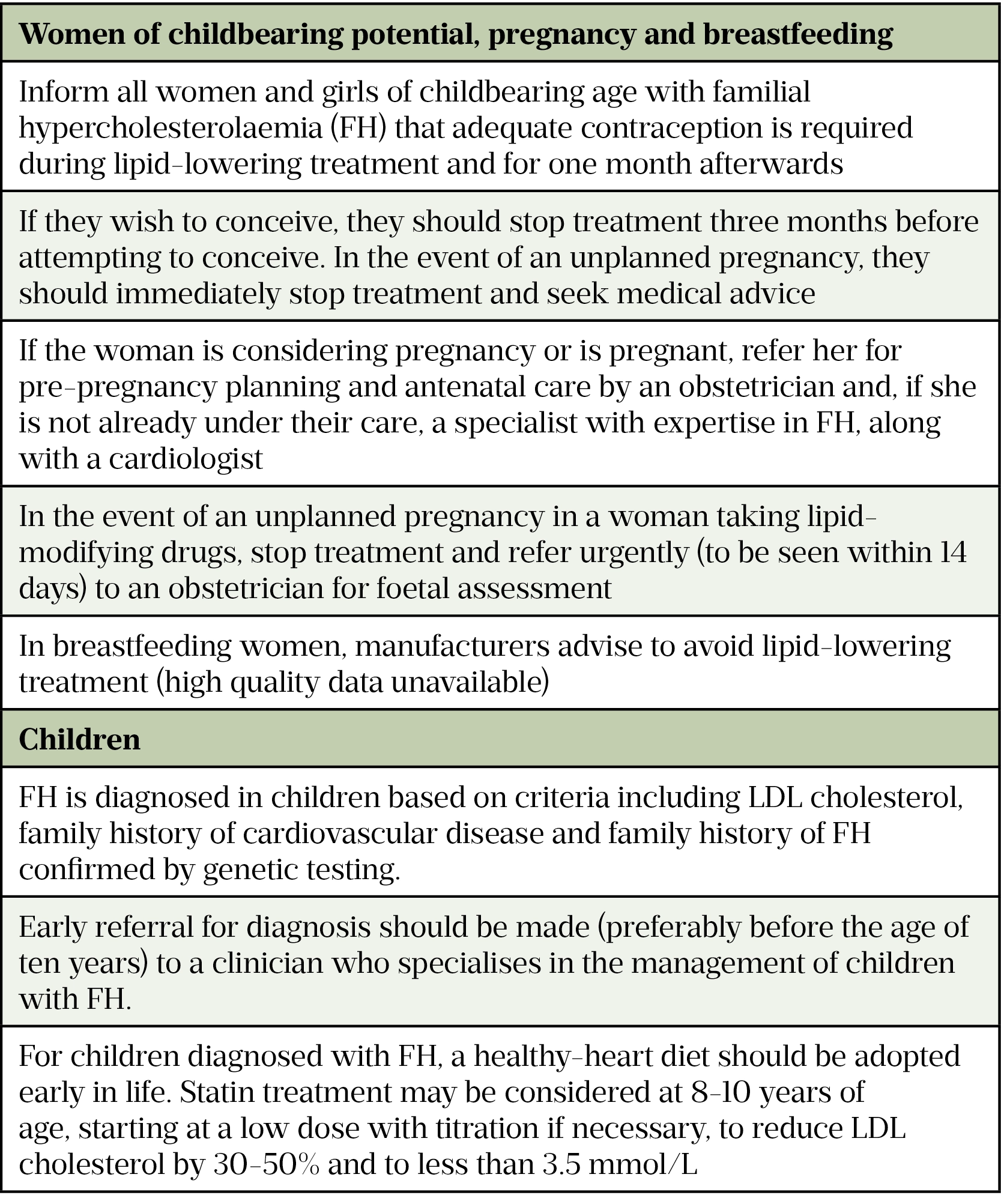

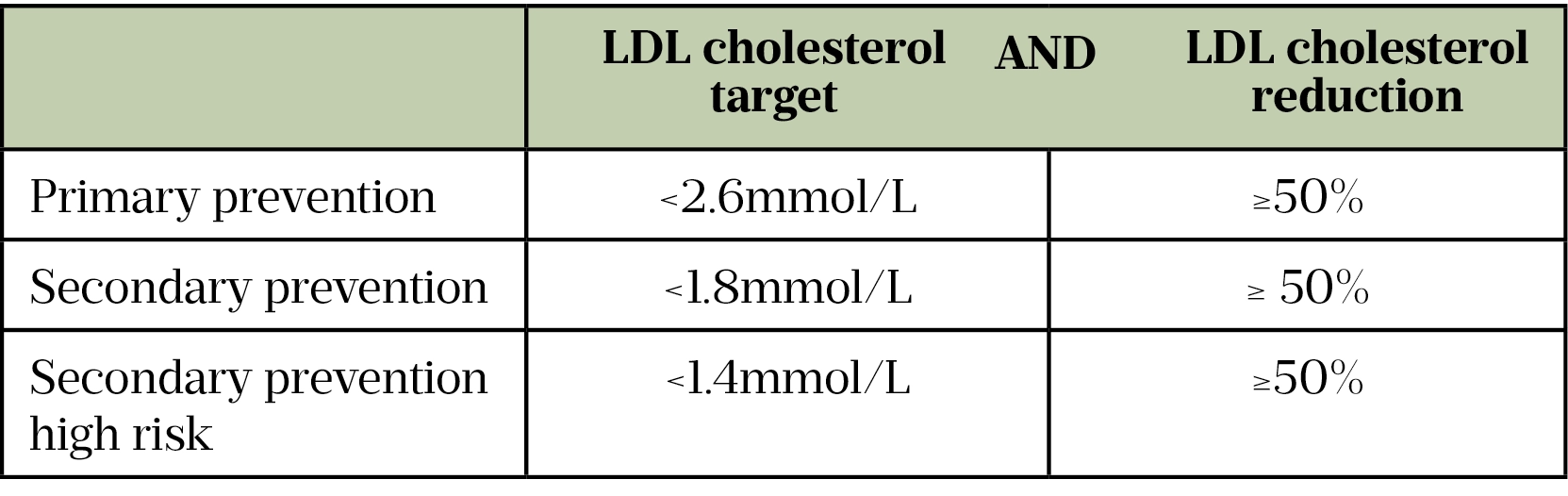

In adults, if not already prescribed, lipid-lowering medication should be initiated as soon as FH is confirmed, but special consideration is needed for women of childbearing potential, and during pregnancy and breastfeeding (see Table 3)[13,17,18]. NICE guidelines recommend a target reduction in LDL cholesterol of at least 50% from baseline[13]. However, this target should be individualised, particularly in patients who are at increased risk of CVD. The target levels from the European Society of Cardiology guidelines are detailed in Table 4[17,19].

Children with suspected or diagnosed FH should be managed by a clinician who specialises in the management of children with FH (Table 3).

Owing to their established role in the prevention and management of atherosclerotic disease, and long-term efficacy in people with FH, statins are considered the first-line treatment[20]. A high-potency statin will usually be required to attain the LDL reduction recommended (e.g. atorvastatin 40–80mg or rosuvastatin 20–40mg)[13].

If there is concern over side effects, lower starting doses may be used. This may be owing to patient-related factors, such as renal function, age, gender, ethnicity or patient preference[21]. Common adverse effects of statins include gastrointestinal disturbances, headache, sleep disorders and dizziness. Less commonly, skin reactions, hepatic disorders, alopecia, memory loss or pancreatitis may occur[22]. Although myalgia has been reported commonly in people receiving statins, serious muscle toxicity (myopathy, myositis and rhabdomyolysis) is rare[22]. When a statin is suspected to be the cause of myopathy, and creatine kinase (CK) concentration is markedly elevated or if muscular symptoms are severe, treatment should be discontinued. However, if symptoms resolve and CK concentrations return to normal, re-introducing the statin at a lower dose with careful monitoring is usually possible. Detailed discussion of statin intolerance is beyond the scope of this article but long-term adherence to treatment is essential and strategies to manage statin intolerance are often required[21].

The pharmacy team should check for any potential drug interactions as a lower starting dose, or a lower maximum recommended dose, may need to be prescribed[23]. Example interactions with atorvastatin include macrolide antibiotics, HIV protease inhibitors, verapamil, diltiazem and amiodarone[23].

Lipid profiles should be checked 8–12 weeks after starting a statin, or after any dose increase, to assess response. If the LDL cholesterol target has not been reached and the patient is not prescribed the maximum recommend dose of statin (taking into account any comorbidities or cautions) an increase in the dose of statin should be offered[13]. However, the prescriber may need to tailor this approach if the patient reports side effects from treatment.

For those patients taking the maximum dose/maximum tolerated dose of statin, treatment intensification is needed. The next step is usually the addition of ezetimibe, which will give a further 12–15% reduction in LDL cholesterol[13]. Alternatively (or in addition), a PCSK9 inhibitor (alirocumab or evolocumab) may be prescribed. In England and Wales, the criteria for NHS funding for the two PCSK9 inhibitors are identical and specified in the NICE technology appraisals, which define patient eligibility based on LDL cholesterol levels and whether the medication is being prescribed for primary or secondary prevention of CVD[24,25]. Although there are no specific trials of the PCSK9 inhibitors in the FH population, there are positive outcome trials in patients with established CVD[26,27]. PCSK9 inhibitors are self-administered by subcutaneous injection with initiation and the ongoing prescription usually managed by specialist lipid services. As part of their role in specialist lipid services, pharmacists may be responsible for the long-term management of patients prescribed PCSK9 inhibitors.

Other medication options, which may be considered if lipid-lowering targets have not been reached/maintained with initial treatments, include bile acid sequestrants, bempedoic acid and inclisaran, although the latter is currently only commissioned via NICE for patients being managed for secondary prevention who, despite maximal tolerated statin therapy, are not treated to target, with the LDL cholesterol remaining above 2.6mmol/L[28,29]. This position may change as further trial data becomes available.

Long term follow-up

Treatment for FH will be needed throughout a person’s life. Once the diagnosis has been made and appropriate treatment has been established, it is essential that patients have ongoing follow up with an appropriately trained healthcare professional. This may be in primary care or may remain in specialist lipid services, depending on the clinical needs of the patient, the medications prescribed and how services are commissioned within the locality. Pharmacists in both primary care and secondary care lipid services can potentially take on this role.

This review may encompass:

- Enquiry into any possible symptoms of CVD;

- Follow up on the progress of cascade testing among relatives;

- Supporting patient’s adherence to lifestyle factors;

- Assessment of lipid profile against treatment targets: medication review, implementation of any required medication changes and assessment of concordance;

- Addressing any contraception or pregnancy-related concerns;

- Addressing patients’ questions or concerns;

- Re-referral to lipid specialist services if further advice is required.

Summary

FH is an under-recognised condition, which carries significant risk of premature CVD. The National Genomic Medicine Service is supporting improved access to genetic testing for diagnosis for patients and their families. Treatment with lipid-lowering therapy is highly effective, although must be maintained lifelong. Pharmacy teams play an important role in the identification and ongoing management of this patient group.

Useful resources

A range of free resources and learning materials are available to support patient and professional education on FH. These include:

- Health Education England Genomics Education Programme: Transformation project resources: Familial hypercholesterolaemia

- Heart UK: Patient and professional information on cholesterol management, including FH.

- 1UK Factsheet January 2022. British Heart Foundation. 2022.https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/our-research/heart-statistics (accessed Jun 2022).

- 2Familial hypercholesterolaemia. Health Education England. 2019.https://www.genomicseducation.hee.nhs.uk/documents/familial-hypercholesterolaemia/ (accessed Jun 2022).

- 3What is familial hypercholesterolaemia? Heart UK. 2022.https://www.heartuk.org.uk/cholesterol/what-is-fh (accessed Jun 2022).

- 4Familial hypercholesterolaemia. NHS England and NHS Improvement London. 2019.www.england.nhs.uk/london/london-clinical-networks/our-networks/cardiac/familial-hypercholesterolaemia/ (accessed Jun 2022).

- 5About familial hypercholesterolemia. National Human Genome Research Institute. 2013.www.genome.gov/Genetic-Disorders/Familial-Hypercholesterolemia (accessed Jun 2022).

- 6Zambon A, Mello e Silva A, Farnier M. The burden of cholesterol accumulation through the lifespan: why pharmacological intervention should start earlier to go further? European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy. 2020;7:435–41. doi:10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa123

- 7NHS long term plan. NHS. 2019.www.longtermplan.nhs.uk (accessed Jun 2022).

- 8Investment and Impact Fund 2022/23 updated guidance. NHS England. 2022.https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/B1357-investment-and-impact-fund-2022-23-updated-guidance-march-2022.pdf (accessed Jun 2022).

- 9Talmud PJ, Shah S, Whittall R, et al. Use of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol gene score to distinguish patients with polygenic and monogenic familial hypercholesterolaemia: a case-control study. The Lancet. 2013;381:1293–301. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)62127-8

- 10National Genomic Test Directory. NHS England. 2022.https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/national-genomic-test-directories/ (accessed Jun 2022).

- 11All Wales Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Service. Cardiff and Vale University Health Board. 2022.https://cavuhb.nhs.wales/our-services/all-wales-familial-hypercholesterolaemia-service/ (accessed Jun 2022).

- 12Cascade testing for familial hypercholesterolaemia. British Heart Foundation. 2022.https://www.bhf.org.uk/for-professionals/healthcare-professionals/innovation-in-care/familial-hypercholesterolaemia-cascade-testing-services (accessed Jun 2022).

- 13Familial hypercholesterolaemia: identification and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG71 (accessed Jun 2022).

- 14Rallidis LS, Iordanidis D, Iliodromitis E. The value of physical signs in identifying patients with familial hypercholesterolemia in the era of genetic testing. Journal of Cardiology. 2020;76:568–72. doi:10.1016/j.jjcc.2020.07.005

- 15Familial hypercholesterolaemia. FH Wales. 2022.https://fhwalescriteria.co.uk/ (accessed Jun 2022).

- 16Eating for lower cholesterol. Heart UK. 2022.https://www.heartuk.org.uk/low-cholesterol-foods/choose-low-cholesterol-foods (accessed Jun 2022).

- 17Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European Heart Journal. 2019;41:111–88. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

- 18Halpern DG, Weinberg CR, Pinnelas R, et al. Use of Medication for Cardiovascular Disease During Pregnancy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73:457–76. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.075

- 19Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. European Heart Journal. 2021;42:3227–337. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484

- 20Versmissen J, Oosterveer DM, Yazdanpanah M, et al. Efficacy of statins in familial hypercholesterolaemia: a long term cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2423–a2423. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2423

- 21Statin Intolerance Pathway. NHS Accelerated Access Collaborative. 2022.https://www.england.nhs.uk/aac/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2020/08/Statin-intolerance-pathway-January-2022.pdf (accessed Jun 2022).

- 22Statins (atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hypercholesterolaemia-familial/prescribing-information/statins-atorvastatin-rosuvastatin-simvastatin/ (accessed Jun 2022).

- 23Statins: interactions, and updated advice for atorvastatin. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2014.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/statins-interactions-and-updated-advice-for-atorvastatin (accessed Jun 2022).

- 24Alirocumab for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA393 (accessed Jun 2022).

- 25Evolocumab for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA394 (accessed Jun 2022).

- 26Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713–22. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1615664

- 27Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097–107. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1801174

- 28Bempedoic acid with ezetimibe for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia. National Institue for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta694 (accessed Jun 2022).

- 29Inclisiran for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA733 (accessed Jun 2022).