LIFE IN VIEW/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the issues that can arise for new pharmacist prescribers;

- Identify the support and structures needed from employers, professional bodies and social networks in order to practice safely, legally and ethically;

- Understand the importance of self-reflection in identifying strengths, weaknesses and gaps in knowledge, as well as limits to practice;

- Manage the expectations of a multidisciplinary team.

Pharmacist independent prescribers (PIPs) can prescribe any medicine for any medical condition, including unlicensed medicines, subject to accepted good clinical practice. They can also prescribe schedule 2, 3, 4, and 5 controlled drugs, including diamorphine hydrochloride, dipipanone and cocaine (for treating organic disease or injury, but not for treating addiction)[1].

The number of registered PIPs in the UK more than tripled between 2016 and 2020, from 2,781 to 8,806[2] PIPs. In Wales alone, more than 16,000 consultations have been delivered by PIPs since 2016[3]. PIPs are now seen as so important to patient care that by 2026, all newly qualified pharmacists in Great Britain will be registered as prescribers[4]. An extra £3m of funding has also been committed for 2022/2023 to boost the prescribing pharmacist workforce in the community sector in Wales[5].

Independent prescribing has extended the role of pharmacists in all areas of practice. Hospital-based PIPs are prescribing across several tertiary care specialties, as well as using their prescribing skills in more generalist roles, such as acute and post-acute medicine. In primary care, PIPs treat acute conditions and long-term physical and mental health conditions. In community pharmacy, PIPs have been commissioned to provide services such as anticoagulation clinics and minor ailment clinics. Community pharmacy is the most challenging sector in which to implement prescribing services owing to several barriers, including lack of access to records, time and peer support[6].

Nonetheless, working as a PIP can provide professional satisfaction and the opportunity to help improve patient safety and outcomes[7]. PIPs are important contributors to multidisciplinary teams (MDTs), working with other healthcare professionals to agree on a patient’s care[8].

The ‘Competency framework for all prescribers‘, published by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, describes best practice, alongside the knowledge and skills required by individuals to prescribe safely and effectively[9].

However, making the transition from pharmacist to PIP can be challenging. Being accountable for prescribing decisions requires a shift in mindset and being comfortable with the grey areas of clinical practice and acceptance of a certain level of risk. This can be difficult in a profession known for being risk-averse[10]. Outlined below are eight strategies to help successfully navigate this shift.

1. Acknowledge and understand that being a PIP is a different role, not just an extension of your current one

A common misconception among pharmacists starting to train as independent prescribers is that they are already making prescribing decisions when they advise other prescribers on changes to medication. However, there is a lot more to the role — The BNF states that PIPs are “responsible and accountable for the assessment of patients with undiagnosed or diagnosed conditions and for decisions about the clinical management required, including prescribing”[11].

PIPs make decisions about the care of a patient without needing to consult another prescriber, and they are accountable for those decisions. This differs from the clinical pharmacist role, in which the pharmacist may make a recommendation, but the prescriber will make and be accountable for that decision. To prepare for this change in level of responsibility, newly qualified prescribers should follow the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) guidance for pharmacist prescribers[9]:

- Ensure they have all the necessary information to prescribe safely;

- Prescribe only within the limits of their knowledge, skills and area of competence;

- Ensure they follow up their prescribing decisions by providing the patient with relevant information, ensuring that any required monitoring is carried out, and that that the patient knows how to seek further help if required.

Employers will often expect PIPs to record, and seek organisational approval for, their scope of practice as a prerequisite to prescribing, and they must only prescribe within the scope described in that document. Providers of professional indemnity insurance may also require a scope of practice document to be in place before suitable cover is issued and PIPs may not be covered if they prescribe outside of this scope.

2. Develop clinical reasoning and decision-making skills

Pharmacists have traditionally based decisions on the science, preferring facts and details over the application of knowledge in uncertain circumstances[10]. Prescribers, on the other hand, must adopt a less risk-averse mindset by incorporating the principles of clinical and diagnostic reasoning.

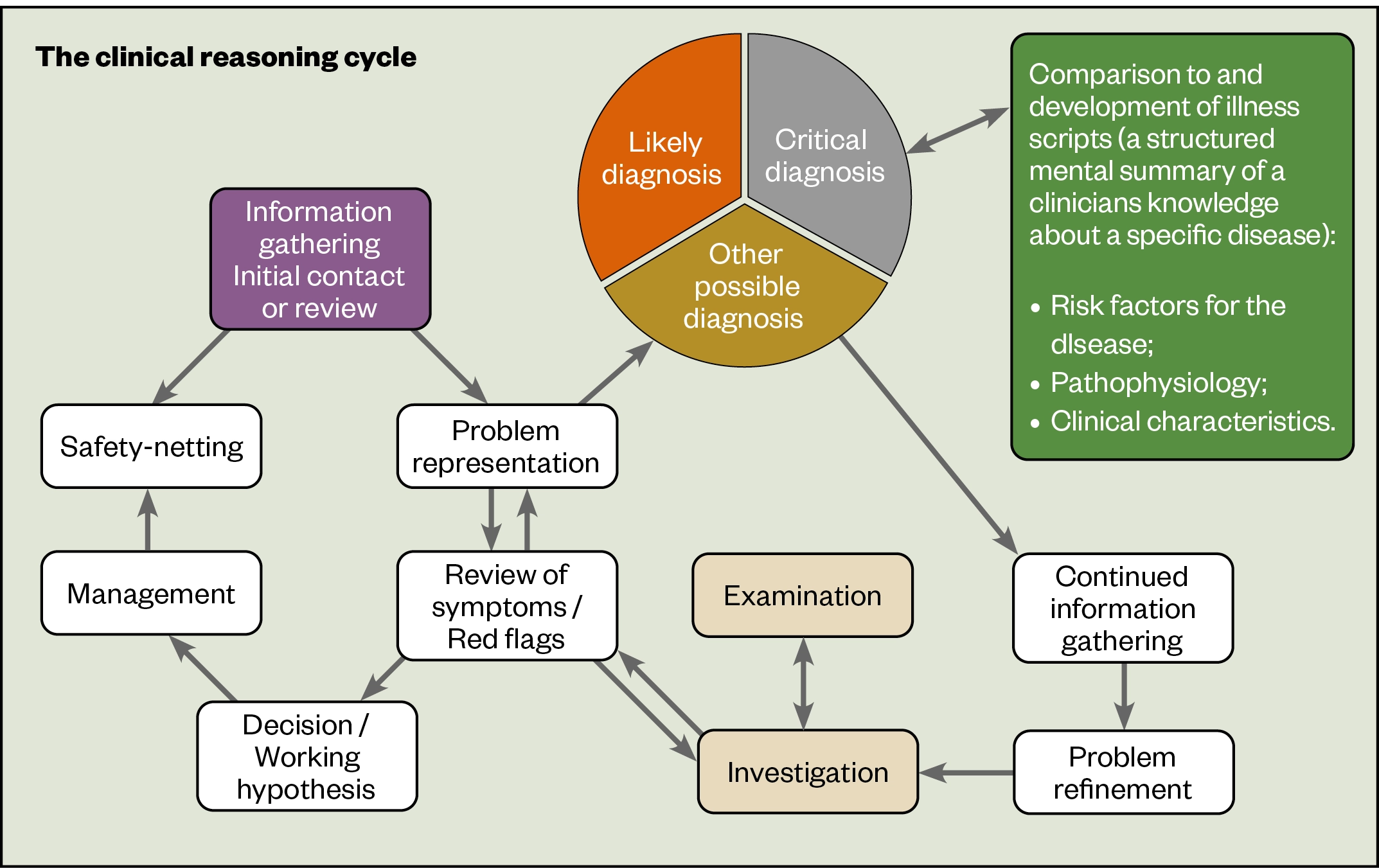

Clinical reasoning is ‘an evidence-based, dynamic process in which the healthcare professional combines scientific knowledge, clinical experience and critical thinking, with existing and newly gathered information about the patient against a backdrop of clinical uncertainty’ (see Figure)[12]. Prescribers must have both in-depth clinical knowledge and robust decision-making skills.

A practical step that newly qualified PIPs can take to improve clinical reasoning is to involve other members of the MDT in prescribing decisions. In secondary care, for example, the pharmacist may discuss prescribing decisions with the medical team during a ward round, or at MDT meetings. In primary care, it might be a discussion with a GP or specialist colleague before or after a consultation. In either sector, the pharmacist can make use of specialist teams in secondary care or community by email or phone for advice.

For more information, see ‘How to use clinical reasoning in pharmacy’.

3. Implement reflective practice

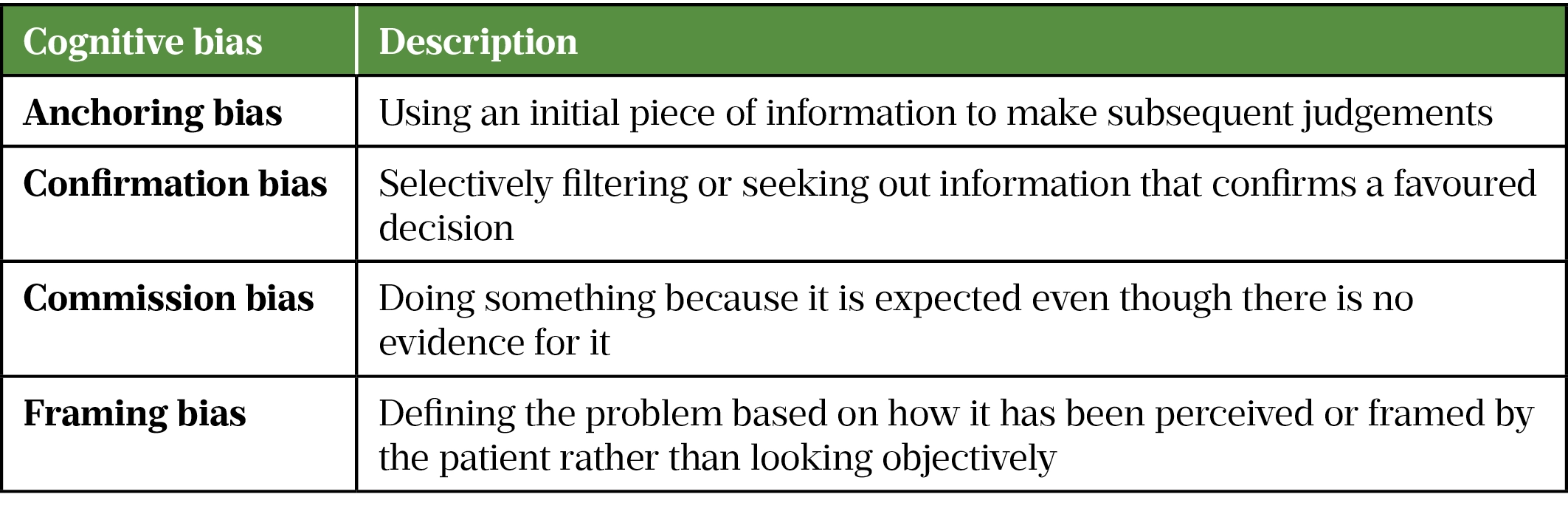

Prescribers must understand the cognitive biases that are present in their decision making (see Table) and recognise the ways in which their own previous experience and external factors, such as the organisation they work in, may influence prescribing. This requires an element of meta-cognition, or ‘thinking about thinking’[14]. The GPhC recommends that PIPs have another person to regularly audit and monitor their prescribing; this could include a peer discussion focusing on their prescribing decisions[9]. These discussions could take the form of a case-based discussion, such as those used during the prescribing course, to help facilitate reflective practice.

4. Critically appraise research data and apply evidence-based practice

Being able to think critically about information (even from reputable sources) and to extract and translate relevant and useful information from the literature is an essential component that allows more effective clinical decisions to be made for patients. Learning how to use the evidence to answer a clinical question, including how to critically appraise the evidence for quality, is essential.

A practical step that pharmacists can take to develop critical analysis skills is to join a journal club that uses a recognised model for critical appraisal of primary research evidence, such as the critical appraisal skills programme[16]. In secondary care, journal clubs tend to exist within specialties, so networking is essential, regardless of the setting. If the meeting is held remotely, why not ask if you can contribute? If you cannot find an existing journal club to join, you could set one up.

5. Become familiar with the different standards that PIPs must meet

PIPs are required by the General Pharmaceutical Council to adhere to the standards set out in the ‘Guidance for pharmacist prescribers‘ in their prescribing practice and must:

- Take responsibility for prescribing safely;

- Keep up to date and prescribe within their competence;

- Work in partnership with other healthcare professionals;

- Factor in considerations and clinical judgement to prescribing approach;

- Know when and how to raise concerns[9].

Newly qualified PIPs should also adhere to all other relevant standards and guidance that apply specifically to the organisation and the role. These may include guidance from the Care Quality Commission, the ‘Competency framework for all prescribers’ and the General Medical Council[6,17,18]. PIPs should also have a good foundational understanding of medicines-related legislation, such as the Medicines Act 1968 and Misuse of Drugs Act 1971[19,20].

6. Understand clinical governance arrangements in your organisation

Employers should have clear lines of responsibility and written procedures within the workplace. There should be clearly defined standard operating procedures (SOPs) for prescribing for non-medical prescribers[21]. For example, in community pharmacy, pharmacists are both prescribing and dispensing a patient’s medication. The SOP in this case should clearly state that a second suitably competent person, such as an accredited checking technician, is to be involved in the checking process.

Clinical governance arrangements in all organisations should allow PIPs to continually improve their prescribing skills. This can be done through regular clinical audits related to their prescribing decisions[22]. PIPs should also be encouraged to participate in audits of the communication pathways they use in order to ensure the correct prescribing-related patient information is included in a timely manner in patients’ medical notes, or when care is transferred to another prescriber (e.g. a GP) or different clinical setting (e.g. community pharmacist to GP).

7. Ensure you have appropriate support in place

Supervisors (such as senior PIPs or advanced clinical practitioners) within the organisation should be involved in setting up peer review, support and mentoring schemes. Peer reviews should be carried out within a structure agreed by your organisation and should concentrate on appropriate elements of practice that encourage positive reflection and discourage blame culture.

PIPs should also be aware of social and wellbeing support available to them within their professional group (such as Pharmacist Support) and employing organisation. This is especially important in the early stages of prescriber accreditation.

8. Agree the scope of the pharmacist’s role

Moving from pharmacist to PIP means a change not just in mindset, but also in the expectations of patients, colleagues and the MDT. Although patients are generally positive about pharmacist prescribing and the role of the pharmacist prescriber in their care, there is a general lack of awareness of this role[23]. Being prepared to explain the role can help manage patient expectations.

A well-publicised conflict of expectations for PIPs working in a GP practice is the signing of repeat prescriptions that the GP has approved as part of the managed repeat prescribing service[24]. Although the signing of prescriptions in this instance could be perceived as an administrative task, the PIP signing the prescription is accountable for that prescription and would be liable for any prescribing errors that might occur. Working as an MDT can improve outcomes for patients and improve job satisfaction for healthcare professionals[25]. However, for these teams to work, the role and responsibility of each professional must be clear. There may be conflicts as other healthcare professionals roles change — for example, nurses, advanced clinical practitioners and physician associates are all starting to take greater responsibility for patient care. Having an agreed scope of practice document can help everyone to understand the PIP’s role.

- 1Non-medical prescribing. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/guidance/non-medical-prescribing.html#:~:text=information%20on%20prescribing.-,Pharmacists,4%2C%20and%205%20Controlled%20Drugs (accessed Apr 2022).

- 2Wickware C. Pharmacist independent prescriber workforce has more than tripled since 2016. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2021.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/news/pharmacist-independent-prescriber-workforce-has-more-than-tripled-since-2016#:~:text=Data%20obtained%20through%20a%20freedom,8%2C806%20on%201%20May%202020 (accessed Apr 2022).

- 3Burns C. Independent prescribing pharmacists deliver 16,000 consultations since 2016. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2021.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/news/independent-prescribing-pharmacists-deliver-16000-consultations-since-2016 (accessed Apr 2022).

- 4Standards for Initial Education and Training of Pharmacists. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2021.https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/education/education-standards (accessed Apr 2022).

- 5Wickware C. Extra £3m for pharmacy training in 2022/2023 to boost independent prescriber workforce. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2021.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/news/extra-3m-for-pharmacy-training-in-2022-2023-to-boost-independent-prescriber-workforce (accessed Apr 2022).

- 6A Competency Framework for all Prescribers. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2020.https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Professional%20standards/Prescribing%20competency%20framework/prescribing-competency-framework.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 7The trials and triumphs of pharmacist independent prescribers. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2018. doi:10.1211/pj.2018.20204489

- 8Song JX, Yue F, Zhou HX, et al. Independent pharmacist prescribers can improve patient pharmacy care. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2020;29:120–120. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2020-002302

- 9In practice: Guidance for pharmacist prescribers. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2020.www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/in-practice-guidance-for-pharmacist-prescribers-february-2020.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 10Rosenthal M, Austin Z, Tsuyuki RT. Are Pharmacists the Ultimate Barrier to Pharmacy Practice Change? Can Pharm J. 2010;143:37–42. doi:10.3821/1913-701x-143.1.37

- 11Non-medical prescribing. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/guidance/non-medical-prescribing.html (accessed Apr 2022).

- 12Rutter PM, Harrison T. Differential diagnosis in pharmacy practice: Time to adopt clinical reasoning and decision making. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2020;16:1483–6. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.020

- 13How to use clinical reasoning in pharmacy. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2022. doi:10.1211/pj.2022.1.124225

- 14Wall T, Kosior K, Ferrero S. The role of metacognition in teaching clinical reasoning: Theory to practice. Educ Health Prof. 2019;2:108. doi:10.4103/ehp.ehp_14_19

- 15Scott IA. Errors in clinical reasoning: causes and remedial strategies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1860–b1860. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1860

- 16CASP checklists. CASP. 2021.https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed Apr 2022).

- 17GP mythbuster 95: non-medical prescribing. Care Quality Commission. 2022.https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/gps/gp-mythbuster-95-non-medical-prescribing (accessed Apr 2022).

- 18Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices. General Medical Council. 2021.https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/good-practice-in-prescribing-and-managing-medicines-and-devices (accessed Apr 2022).

- 19Medicines Act 1968. UK Government. 2022.https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1968/67/contents (accessed Apr 2022).

- 20Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. UK Government. 2022.https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1971/38/contents (accessed Apr 2022).

- 21Non-Medical Prescribing within Planned Care Community Mental Health Teams. Black Country Partnership NHS Foundation Trust. 2019.https://www.bcpft.nhs.uk/about-us/our-policies-and-procedures/n/2179-non-medical-prescribing-sop-03-within-planned-care-community-mental-health-teams/file (accessed Apr 2022).

- 22Ashmore S, Chanter C, Johnson T. A guide to clinical audit — Appendix 7. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. 2008.https://psnc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/a_guide_to_clinical_audit.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 23McCann LM, Haughey SL, Parsons C, et al. A patient perspective of pharmacist prescribing: ‘crossing the specialisms-crossing the illnesses’. Health Expect. 2012;18:58–68. doi:10.1111/hex.12008

- 24Webb A. Surgery Repeat Prescription Programme. Pharmacist Defence Association. 2016.https://www.the-pda.org/?policy-extension=policy-extension-6 (accessed Apr 2022).

- 25Delivering integrated care: the role of the multidisciplinary team. Social Care Institute for Excellence. 2018.https://www.scie.org.uk/integrated-care/workforce/role-multidisciplinary-team (accessed Apr 2022).